Doping in Cycling: Incentivizing the Reporting of UCI Anti-Doping Rules Violations Through Organizational Oversight and Accountability, 49 J

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Review of Criminalisation of Doping in Sport

Review of Criminalisation of Doping in Sport October 2017 Review of Criminalisation of Doping in Sport 1 of 37 Foreword The UK has always taken a strong stance against doping; taking whatever steps are necessary to ensure that the framework we have in place to protect the integrity of sport is fully robust and meets the highest recognised international standards. This has included becoming a signatory to UNESCO’s International Convention Against Doping in Sport; complying with the World Anti-Doping Code; and establishing UK Anti-Doping as our National Anti-Doping Organisation. However, given the fast-moving nature of this area, we can never be complacent in our approach. The developments we have seen unfold in recent times have been highly concerning, not least with independent investigations commissioned by the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) revealing large scale state-sponsored doping in Russia. With this in mind, I tasked officials in my Department to undertake a Review to assess whether the existing UK framework remains sufficiently robust, or whether additional legislative measures are necessary to criminalise the act of doping in the UK. This Review was subsequently conducted in two stages: (i) a comprehensive assessment of the effectiveness of the UK’s existing anti-doping measures and compliance with WADA protocols, and (ii) targeted interviews with key expert stakeholders on the merits of strengthening UK anti-doping provisions, including the feasibility and practicalities of criminalising the act of doping. As detailed in this report, the Review finds that, at this current time, there is no compelling case to criminalise the act of doping in the UK. -

Case – Tdf Diagnostic Hypotheses 2013

____________________ ____________________ ____________________ ____________________ ____________________ ____________________ ____________________ ____________________ ____________________ ____________________ ____________________ ____________________ Froome's performances since the Vuelta 11 are so good that he should be considered a Grand Tour champion. Grand Tour champions who didn't benefit from game-changing drugs (GTC) usually display a high potential as junior athletes. Supporting evidence: Coppi first won the Giro at 20 Anquetil first won the Grand Prix des Nations at 19 Merckx won the world's road at 19 Hinault won the Giro and Tour at 24 LeMond showed amazing talent at just 15 Fignon led the Giro and won the Critèrium national at 22 No display of early talent H: Froome rode the 2013 TdF 'clean' ~H: Froome didn't ride the 2013 TdF 'clean' Reason: Because p(D|H) = Objection: But that's because he grew up in Evaluation Froome didn't display a high Froome's first major wins a country with no cycling activity per say and p(D|~H) = potential as a junior athlete. were at age 26, which is he took up road racing late. quite late in cycling. Cognitive dissonance (additional condition): Being clean, Froome performs at a Grand Tour champion level despite not having shown great potential as a junior athlete. Requirement: it is possible to be a clean Grand Tour champion without showing high potential as a junior athlete. Armstrong's performance in the TdF: DNF, DNF, 36, DNF, DNS [cancer], DNS [cancer], 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 3, 23 Sudden metamorphoses from 'middle of the pack' to 'champion' are Team Sky's director Brailsford: "We also look at the history of the guy, his usually seen in dopers. -

Relation Between Exercise Performance and Blood Storage Condition and Storage Time in Autologous Blood Doping

biology Review Relation between Exercise Performance and Blood Storage Condition and Storage Time in Autologous Blood Doping Benedikt Seeger and Marijke Grau * Molecular and Cellular Sports Medicine, German Sport University Cologne, 50677 Cologne, Germany; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +49-221-4982-6116 Simple Summary: Autologous blood doping (ABD) refers to sampling, storage, and re-infusion of one’s own blood to improve circulating red blood cell (RBC) mass and thus the oxygen transport and finally the performance capacity. This illegal technique employed by some athletes is still difficult to detect. Hence knowledge of the main effects of ABD is needed to develop valid detection methods. Performance enhancement related to ABD seems to be well documented in the literature, but applied study designs might affect the outcome that was analyzed herein. The majority of recent studies investigated the effect of cold blood storage at 4 ◦C, and only few studies focused on cryopreservation, although it might be suspected that cryopreservation is above all applied in sport. The storage duration—the time between blood sampling and re-infusion—varied in the reported literature. In most studies, storage duration might be too short to fully restore the RBC mass. It is thus concluded that most reported studies did not display common practice and that the reported performance outcome might be affected by these two variables. Thus, knowledge of the real effects of ABD, as applied in sport, on performance and associated parameters are needed to develop reliable detection techniques. Abstract: Professional athletes are expected to continuously improve their performance, and some might also use illegal methods—e.g., autologous blood doping (ABD)—to achieve improvements. -

The Wisdom of Géminiani ROULEUR MAGAZINE

The Wisdom of Géminiani ROULEUR MAGAZINE Words: Isabel Best 28 June, 1947 It’s the first Tour de France since the war; No one apart from Géminiani, Anquetil’s the year René Vietto unravels and loses his directeur sportif. You can see him in the yellow jersey on a 139k time-trial. The year background, standing up through the Breton schemer Jean Robic attacks—and sunroof of the team car. “There was no wins—on the final stage into Paris. But on more a duel than there were flying pigs,” this particular day, in a tarmac-melting Géminiani recalled many years later. heatwave, a young rider called Raphaël “When you’re at your limits in the Géminiani is so desperately thirsty, he gets mountains, you should never sit on your off his bike to drink out of a cattle trough, rival’s wheel. You have to ride at his side. thereby catching foot and mouth disease. It’s an old trick. With Anquetil at his level, Not the most auspicious of Tour beginnings Poulidor was wondering what was going for a second year pro. on. He thought maybe Jacques was stronger than him. Well, you can see, he 18 July, 1955 wasn’t looking great. Only, an Anquetil Another heatwave. This time on Mont who’s not in top form is still pretty good.” Ventoux. Géminiani is in the break, with the Swiss champion Ferdi Kübler and a French regional rider, Gilbert Scodeller. Ferdi A few snapshots from the 50 Tours de attacks. “Be careful, Ferdi; The Ventoux is France of Raphaël Géminiani. -

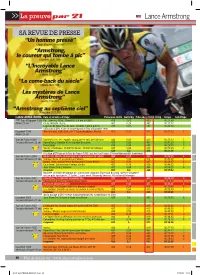

Armstrong.Pdf

>> La preuve par 21 Lance Armstrong SA REVUE DE PRESSE “Un homme pressé” L’Equipe Magazine, 04.09.1993 “Armstrong, le coureur qui tombe à pic” L’Humanité, 05.07.1999 “L’Incroyable Lance Armstrong” L’Equipe, 12.07.1999 “Le come-back du siècle” L’Equipe, 26.07.1999 “Les mystères de Lance Armstrong” Le JDD, 27.06.2004 “Armstrong au septième ciel” Le Midi Libre, 25.07.2005 Lance ARMSTRONG Cols et victoires d’étape Puissance réelle watts/kg Puissance étalon 78 kg temps Cols Etape Tour Tour d’Espagne 1998 Pal. Jimenez 433w, 20min30s, 8,4 km à 6,49%, 418 5,65 400 00:21:49 4ème-27 ans Cerler. Montée courte. 462 6,24 442 00:11:33 Lagunas de Neila. Peu de vent, en forêt, 7 km à 8,57%, 415 5,61 397 00:22:18 Utilisation d’EPO et de cortisone durant le Tour d’Espagne 1998 Dauphiné 1999 Mont Ventoux CLM. ‘Battu de 1’1s par Vaughters. Record. 455 6,15 432 00:57:52 1 8ème-28 ans Tour de France 2004 La Mongie. 2ème derrière Basso 487 6,58 462 00:23:15 2 Tour de France 1999 Sestrières 1er. 1er «exploit» marquant en solo. Vent de face 448 6,05 420 00:27:13 5 1er puis déclassé-33 ans Beille 1er. En solitaire. 438 5,92 416 00:45:40 6 1er puis déclassé-28 ans Alpe d’Huez. Contrôle et se contente de suivre. 436 5,89 407 00:41:20 3 Chalimont 1er. Victoire à Villard de Lans 410 5,54 392 00:19:05 3 Piau Engaly 395 5,34 385 00:26:15 5 Alpe d’Huez CLM 1er. -

A Legal Analysis of the WADA-Code Beyond the Contador Case

A legal analysis of the WADA-code beyond the Contador case Faculty: Tilburg Law School Department: Social Law and Social Politics Master: International and European Labour Law Author: Lonneke Zandberg Student number: 537776 Graduation date: March 14, 2012 Exam Committee: Prof. dr. M. Colucci Prof. dr. F.H.R. Hendrickx Table of contents: LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS ...................................................................................................................... 4 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................ 5 1. HISTORY OF ANTI-DOPING .................................................................................................... 7 2. WADA .................................................................................................................................. 8 2.1 The arise of WADA .............................................................................................................. 8 2.2 World Anti Doping Code 2009 (WADA-code) ..................................................................... 8 2.3 The binding nature of the WADA-code ............................................................................. 10 2.4 Compliance and monitoring of the WADA-code .............................................................. 11 2.5 Sanctions for athletes after violating the WADA-code ..................................................... 12 3. HOW TO DEAL WITH A POSITIVE DOPING RESULT AFTER AN ATHLETE HAS EATEN CONTAMINATED -

Lance Armstrong Has Something to Get Off His Chest

Texas Monthly July 2001: Lanr^ Armstrong Has Something to . Page 1 of 17 This copy is for your personal, non-commercial use only. For public distribution to your colleagues, clients or customers, contact [email protected] for reprint information and fees. (EJiiPfflNITHIS Lance Armstrong Has Something to Get Off His Chest He doesn't use performance-enhancing drugs, he insists, no matter what his critics in the European press and elsewhere say. And yet the accusations keep coming. How much scrutiny can the two-time Tour de France winner stand? by Michael Hall In May of last year, Lance Armstrong was riding in the Pyrenees, preparing for the upcoming Tour de France. He had just completed the seven-and-a-half-mile ride up Hautacam, a treacherous mountain that rises 4,978 feet above the French countryside. It was 36 degrees and raining, and his team's director, Johan Bruyneel, was waiting with a jacket and a ride back to the training camp. But Lance wasn't ready to go. "It was one of those moments in my life I'll never forget," he told me. "Just the two of us. I said, 'You know what, I don't think I got it. I don't understand it.1 Johan said, 'What do you mean? Of course you got it. Let's go.' I said, 'No, I'm gonna ride all the way down, and I'm gonna do it again.' He was speechless. And I did it again." Lance got it; he understood Hautacam—in a way that would soon become very clear. -

Jalabert Rattrapé Par Son Ombre

MARDI 25 JUIN 2013 15 CYCLISME Jalabert rattrapé par son ombre La commission d’enquête sénatoriale a rassemblé les éléments qui prouvent que le champion français était positif à l’EPO lors du Tour de France 1998. DES TRACES D’EPO synthétique Sports et autres autorités concer- La positivité du natif de Mazamet 84 personnes en quatre mois ont été retrouvées dans les urines nées les procès-verbaux nomi- est donc indiscutable. Néan- dans les murs du palais du de Laurent Jalabert prélevées le natifs lui permettant d’identifier moins, il ne s’agit pas d’un con- Luxembourg, Laurent Jalabert, 22 juillet 1998 à l’issue de la les coureurs prélevés. Bien dans trôle antidopage. Donc, à l’instar gravement accidenté le 11 mars 11e étapeduTourdeFrancereliant le ton de ce que fut ce Tour des des échantillons de Lance Arms- dernier lors d’une sortie d’entraî- Luchon au plateau de Beille (rem- garde à vue et des descentes de trong, cette analyse n’a en aucun nement, n’a pour autant pas réel- portée par Marco Pantani). L’in- police, la quasi-totalité des cas de portée disciplinaire, a for- lement menti, ce qui aurait pu lui formation analytique, que échantillons de 1998 réanalysés tiori quinze ans après les faits. Ja- valoir une sanction pénale. L’Équipe estenmesurededivul- par le laboratoire francilien se labert ne risque aucune sanction Alors que dans son propos li- guer aujourd’hui, est consécutive sont avérés positifs à l’EPO en rétroactive. minaire, Jean-Jacques Lozach, au même genre de tests qui ont 2004 (1), ce qui s’explique par le « ON ÉTAIT SOIGNÉS, sénateurdelaCreuse,trèsfair- confondu inéluctablement Lance fait que les coureurs ne risquaient MAIS ÉTAIT-ON play, lui rappelait que la commis- Armstrong dans ces colonnes, le rien en la circonstance puisque DOPÉS ? sion d’enquête avait récupéré SAINT-QUENTIN peux assurer qu’à aucun mo- pés?Jenelecroispas.»Interrogé (1) Face aux résultats de détection 23 août 2005. -

A Genealogy of Top Level Cycling Teams 1984-2016

This is a work in progress. Any feedback or corrections A GENEALOGY OF TOP LEVEL CYCLING TEAMS 1984-2016 Contact me on twitter @dimspace or email [email protected] This graphic attempts to trace the lineage of top level cycling teams that have competed in a Grand Tour since 1985. Teams are grouped by country, and then linked Based on movement of sponsors or team management. Will also include non-gt teams where they are “related” to GT participants. Note: Due to the large amount of conflicting information their will be errors. If you can contribute in any way, please contact me. Notes: 1986 saw a Polish National, and Soviet National team in the Vuelta Espana, and 1985 a Soviet Team in the Vuelta Graphics by DIM @dimspace Web, Updates and Sources: Velorooms.com/index.php?page=cyclinggenealogy REV 2.1.7 1984 added. Fagor (Spain) Mercier (France) Samoanotta Campagnolo (Italy) 1963 1964 1965 1966 1967 1968 1969 1970 1971 1972 1973 1974 1975 1976 1977 1978 1979 1980 1981 1982 1983 1984 1985 1986 1987 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 Le Groupement Formed in January 1995, the team folded before the Tour de France, Their spot being given to AKI. Mosoca Agrigel-La Creuse-Fenioux Agrigel only existed for one season riding the 1996 Tour de France Eurocar ITAS Gilles Mas and several of the riders including Jacky Durant went to Casino Chazal Raider Mosoca Ag2r-La Mondiale Eurocar Chazal-Vetta-MBK Petit Casino Casino-AG2R Ag2r Vincent Lavenu created the Chazal team. -

Social Psychology of Doping in Sport: a Mixed-Studies Narrative Synthesis

Social psychology of doping in sport: a mixed-studies narrative synthesis Prepared for the World Anti-Doping Agency By the Institute for Sport, Physical Activity and Leisure Review Team The review team comprised members of the Carnegie Research Institute at Leeds Beckett University, UK. Specifically the team included: Professor Susan Backhouse, Dr Lisa Whitaker, Dr Laurie Patterson, Dr Kelsey Erickson and Professor Jim McKenna. We would like to acknowledge and express our thanks to Dr Suzanne McGregor and Miss Alexandra Potts (both Leeds Beckett University) for their assistance with this review. Address for correspondence: Professor Susan Backhouse Institute for Sport, Physical Activity and Leisure Leeds Beckett University, Headingly Campus Leeds, LS6 3QS UK Email: [email protected] Web: www.leedsbeckett.ac.uk/ISPAL Disclaimer: The authors undertook a thorough search of the literature but it is possible that the review missed important empirical studies/theoretical frameworks that should be included. Also, judgement is inevitably involved in categorising papers into sample groups and there are different ways of representing the research landscape. We are not suggesting that the approach presented here is optimal, but we hope it allows the reader to appreciate the breadth and depth of research currently available on the social psychology of doping in sport. October 2015 2 Table of Contents Executive Summary .................................................................................................................. 6 Introduction -

22 Marzo 2015 • Sunday, 22Nd March 2015 293 Km Il “Festival Del Ciclismo” | the “Cycling Festival”

rzo 22 Ma 2015 OPS Milano_Sanremo 2015 no sponsor.indd 1 13/03/15 15:13 2 Domenica 22 Marzo 2015 • Sunday, 22nd March 2015 293 km Il “FESTIVAL DEL CICLISMO” | THE “CYCLING FESTIVAL” La Milano-Sanremo comincia con l’ultimo giorno d’inverno e finisce Milano-Sanremo starts on the last day of winter and ends on the first con il primo giorno di primavera, anche se piove o nevica, perché da day of spring, even in the rain or snow, because there are no transitional tempo non esistono più le mezze stagioni ma l’unica stagione sempre seasons only more, only the eternal present of a cycling season that is attuale è quella del ciclismo, che con il tempo si è allungata e allargata, longer and broader than ever, and once extended from Milano-Sanremo prima andava dalla Milano-Sanremo al Giro di Lombardia e adesso va to the the Giro d’Italia di Lombardia but now begins in Africa and ends dall’Africa alla Cina. in China. La Milano-Sanremo è la storia che abita la geografia ed è la geogra- Milano-Sanremo is history that inhabits geography, geography made fia che si umanizza nella storia, però è anche scienze, applicazioni human in history, but it is also applied science, technology, and a lot tecniche e moltissima educazione fisica, è italiano, che continua of physical education. It is Italian, which is still the language spoken a essere la lingua del gruppo, però è sempre francese e sempre più in the peloton, but it remains French, and is becoming increasingly inglese, è anche religione, tutti credenti nella bicicletta come simbolo English. -

9781781316566 01.Pdf

CONTENTS 1 The death of Fausto 7 Nairo Quintana is born 12 Maurice Garin is born 17 Van Steenbergen wins 27 Henri Pélissier, convict 37 The first Cima Coppi Coppi 2 January 4 February 3 March Flanders 2 April of the road, is shot dead 4 June 2 Thomas Stevens cycles 8 The Boston Cycling Club 13 First Tirenno–Adriatico 18 71 start, four finish 1 May 38 Gianni Bugno wins round the world is formed 11 February starts 11 March Milan–Sanremo 3 April 28 The narrowest ever the Giro 6 June 4 January 9 Marco Pantani dies 14 Louison Bobet dies 19 Grégory Baugé wins Grand Tour win is 39 LeMond’s comeback 3 Jacques Anquetil is 14 February 13 March seventh world title recorded 6 May 11 June born 8 January 10 Romain Maes dies 15 First Paris–Nice gets 7 April 29 Beryl Burton is born 40 The Bernina Strike 4 The Vélodrome d’Hiver 22 February underway 14 March 20 Hinault wins Paris– 12 May 12 June hosts its first six-day 11 Djamolidine 16 Wim van Est is born Roubaix 12 April 30 The first Giro d’Italia 41 Ottavio Bottecchia fatal race 13 January Abdoujaparov is born 25 March 21 Fiftieth edition of Paris– starts 13 May training ride ‘accident’ 5 The inaugural Tour 28 February Roubaix 13 April 31 Willie Hume wins in 14 June Down Under 19 January 22 Fischer wins first Hell of Belfast and changes 42 Franceso Moser is born 6 Tom Boonen’s Qatar the North 19 April cycle racing 18 May 19 June dominance begins 23 Hippolyte Aucouturier 32 Last Peace Race finishes 43 The longest Tour starts 30 January dies 22 April 20 May 20 June 24 The Florist wins Paris– 33 Mark Cavendish