Developing a Critical Horology to Rethink the Potential of Clock Time’ in New Formations (Special Issue: Timing Transformations)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How Long Is a Year.Pdf

How Long Is A Year? Dr. Bryan Mendez Space Sciences Laboratory UC Berkeley Keeping Time The basic unit of time is a Day. Different starting points: • Sunrise, • Noon, • Sunset, • Midnight tied to the Sun’s motion. Universal Time uses midnight as the starting point of a day. Length: sunrise to sunrise, sunset to sunset? Day Noon to noon – The seasonal motion of the Sun changes its rise and set times, so sunrise to sunrise would be a variable measure. Noon to noon is far more constant. Noon: time of the Sun’s transit of the meridian Stellarium View and measure a day Day Aday is caused by Earth’s motion: spinning on an axis and orbiting around the Sun. Earth’s spin is very regular (daily variations on the order of a few milliseconds, due to internal rearrangement of Earth’s mass and external gravitational forces primarily from the Moon and Sun). Synodic Day Noon to noon = synodic or solar day (point 1 to 3). This is not the time for one complete spin of Earth (1 to 2). Because Earth also orbits at the same time as it is spinning, it takes a little extra time for the Sun to come back to noon after one complete spin. Because the orbit is elliptical, when Earth is closest to the Sun it is moving faster, and it takes longer to bring the Sun back around to noon. When Earth is farther it moves slower and it takes less time to rotate the Sun back to noon. Mean Solar Day is an average of the amount time it takes to go from noon to noon throughout an orbit = 24 Hours Real solar day varies by up to 30 seconds depending on the time of year. -

Chapter 8: Geologic Time

Chapter 8: Geologic Time 1. The Art of Time 2. The History of Relative Time 3. Geologic Time 4. Numerical Time 5. Rates of Change Copyright © The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. Permission required for reproduction or display. Geologic Time How long has this landscape looked like this? How can you tell? Will your grandchildren see this if they hike here in 80 years? The Good Earth/Chapter 8: Geologic Time The Art of Time How would you create a piece of art to illustrate the passage of time? How do you think the Earth itself illustrates the passage of time? What time scale is illustrated in the example above? How well does this relate to geological time/geological forces? The Good Earth/Chapter 8: Geologic Time Go back to the Table of Contents Go to the next section: The History of (Relative) Time The Good Earth/Chapter 8: Geologic Time The History of (Relative) Time Paradigm shift: 17th century – science was a baby and geology as a discipline did not exist. Today, hypothesis testing method supports a geologic (scientific) age for the earth as opposed to a biblical age. Structures such as the oldest Egyptian pyramids (2650-2150 B.C.) and the Great Wall of China (688 B.C.) fall within a historical timeline that humans can relate to, while geological events may seem to have happened before time existed! The Good Earth/Chapter 8: Geologic Time The History of (Relative) Time • Relative Time = which A came first, second… − Grand Canyon – B excellent model − Which do you think happened first – the The Grand Canyon – rock layers record thousands of millions of years of geologic history. -

Sidereal Time 1 Sidereal Time

Sidereal time 1 Sidereal time Sidereal time (pronounced /saɪˈdɪəri.əl/) is a time-keeping system astronomers use to keep track of the direction to point their telescopes to view a given star in the night sky. Just as the Sun and Moon appear to rise in the east and set in the west, so do the stars. A sidereal day is approximately 23 hours, 56 minutes, 4.091 seconds (23.93447 hours or 0.99726957 SI days), corresponding to the time it takes for the Earth to complete one rotation relative to the vernal equinox. The vernal equinox itself precesses very slowly in a westward direction relative to the fixed stars, completing one revolution every 26,000 years approximately. As a consequence, the misnamed sidereal day, as "sidereal" is derived from the Latin sidus meaning "star", is some 0.008 seconds shorter than the earth's period of rotation relative to the fixed stars. The longer true sidereal period is called a stellar day by the International Earth Rotation and Reference Systems Service (IERS). It is also referred to as the sidereal period of rotation. The direction from the Earth to the Sun is constantly changing (because the Earth revolves around the Sun over the course of a year), but the directions from the Earth to the distant stars do not change nearly as much. Therefore the cycle of the apparent motion of the stars around the Earth has a period that is not quite the same as the 24-hour average length of the solar day. Maps of the stars in the night sky usually make use of declination and right ascension as coordinates. -

Tennessee Hunting Seasons Summary 2021-22

2021-22 Tennessee Hunting Seasons Summary Please refer to the Tennessee Hunting and Trapping Guide for detailed hunting dates, bag limits, zones, units, and required licenses and/or permits. G = Gun • M = Muzzleloader • A = Archery • S = Shotgun DEER SPRING TURKEY Statewide bag limit: 2 antlered deer. No more than 1 per day. See the Tennes- S/A Young Sportsman (ages 6-16) Mar. 26-27, 2022* see Hunting and Trapping Guide for deer units and county listings. Daily bag: 1 bearded turkey per day. Counts toward spring A Aug. 27-29 Units A, B, C, D, L season bag of three (3). Private land, antlered deer only. S/A General Season April 2 - May 15, 2022* G/M/A Aug. 27-29 Unit CWD Bag limit: 3 bearded turkeys, no more than 1 per day. Antlered deer only. Private lands and select public lands (see hunting guide). *Some west and southern middle Tennessee counties have shortened seasons A Sep. 25-Oct. 29, Nov. 1-5 Statewide and reduced bag limits. See the Tennessee Hunting and Trapping Guide for Antlerless bag: Units A, B, C, D=4; Units L, CWD=3/day, no more information. season limit G/M/A Oct. 30 - Oct. 31, Jan. 8-9, 2022 Statewide GAME BIRDS Young Sportsman (ages 6-16). Antlerless bag: Units A, B, C, D=2; Units L, CWD=3/day Grouse Oct. 9- Feb. 28, 2022: Daily bag 3 M/A Nov. 6-19 Units A, B, C, D, L Quail Nov. 6 - Feb. 28, 2022: Daily bag 6 Antlerless bag: Units A, B=2; Units C, D=1; Unit L=3/day G/M/A Nov. -

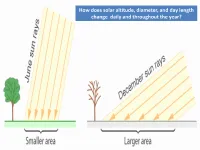

How Does Solar Altitude, Diameter, and Day Length Change Daily and Throughout the Year?

How does solar altitude, diameter, and day length change daily and throughout the year? Let’s prove distance doesn’t matter in seasons by investigating SOLAR ALTITUDE, DAY LENGTH and SOLAR DISTANCE… Would the sun have the same appearance if you observed it from other planets? Why do we see the sun at different altitudes throughout the day? We use the altitude of the sun at a time called solar “noon” because of daily solar altitude changes from the horizon at sunrise and sunset to it’s maximum daily altitude at noon. If you think solar noon is at 12:00:00, you’re mistaken! Solar “noon” doesn’t usually happen at clock-noon at your longitude for lots of reasons! SOLAR INTENSITY and ALTITUDE - Maybe a FLASHLIGHT will help us see this relationship! Draw the beam shape for 3 solar altitudes in your notebooks! How would knowing solar altitude daily and seasonally help make solar panels (collectors)work best? Where would the sun have to be located to capture the maximum amount of sunlight energy? Draw the sun in the right position to maximize the light it receives on panel For the northern hemisphere, in which general direction would they be pointed? For the southern hemisphere, in which direction would they be pointed? SOLAR PANELS at different ANGLES ON GROUND How do shadows show us solar altitude? You used a FLASHLIGHT and MODELING CLAY to show you how SOLAR INTENSITY, ALTITUDE, and SHADOW LENGTH are related! Using at least three solar altitudes and locations, draw your conceptual model of this relationship in your notebooks… Label: Sun compass direction Shadow compass direction Solar altitude Shadow length (long/short) Sun intensity What did the lab show us about how SOLAR ALTITUDE, DIAMETER, & DAY LENGTH relate to each other? YOUR GRAPHS are PROBABLY the easiest way to SEE the RELATIONSHIPS. -

Governing the Time of the World Written by Tim Stevens

Governing the Time of the World Written by Tim Stevens This PDF is auto-generated for reference only. As such, it may contain some conversion errors and/or missing information. For all formal use please refer to the official version on the website, as linked below. Governing the Time of the World https://www.e-ir.info/2016/08/07/governing-the-time-of-the-world/ TIM STEVENS, AUG 7 2016 This is an excerpt from Time, Temporality and Global Politics – an E-IR Edited Collection. Available now on Amazon (UK, USA, Ca, Ger, Fra), in all good book stores, and via a free PDF download. Find out more about E-IR’s range of open access books here Recent scholarship in International Relations (IR) is concerned with how political actors conceive of time and experience temporality and, specifically, how these ontological and epistemological considerations affect political theory and practice (Hutchings 2008; Stevens 2016). Drawing upon diverse empirical and theoretical resources, it emphasises both the political nature of ‘time’ and the temporalities of politics. This chronopolitical sensitivity augments our understanding of international relations as practices whose temporal dimensions are as fundamental to their operations as those revealed by more established critiques of spatiality, materiality and discourse (see also Klinke 2013). This transforms our understanding of time as a mere backdrop to ‘history’ and other core concerns of IR (Kütting 2001) and provides opportunities to reflect upon the constitutive role of time in IR theory itself (Berenskoetter 2011; Hom and Steele 2010; Hutchings 2007; McIntosh 2015). One strand of IR scholarship problematises the historical emergence of a hegemonic global time that subsumed within it local and indigenous times to become the time by which global trade and communications are transacted (Hom 2010, 2012). -

Physics: Sundial Science

Physics: Sundial Science MAIN IDEA Discover how the sun and its shadow is used to tell time by creating a sundial – an instrument that tracks the position of the sun to indicate time of day. SCIENCE BACKGROUND For centuries humans, have utilized the power of the sun as a light source, to grow food, and to tell time. Ancient civilizations used the sun to understand basic astronomy. By tracking the height of the sun in the sky, these civilizations developed calendars for the year and were able to identify harvesting and planting seasons (fall and spring equinoxes) all by tracking the movement of the sun. This also helped certain civilizations find the Equator, an imaginary circle around the Earth that divides it into two halves, the northern and southern hemisphere. By tracking the sun’s apparent position through the creation of sundials, these ancient civilizations were able to divide the day into morning and afternoon. A sundial is a device used to track time by marking a shadow on its surface as the sun moves. Light travels as a wave, similar to waves in the ocean. Shadows occur when this light wave is blocked by an object, creating a dark silhouette of that object on nearby surfaces as light continues to travel all around the object. Based on where the light source is, and the object that is blocking it, the shadow will look different. This is why for a sundial, the shadow will change throughout the day and even more noticeably throughout the year for the same time of day. -

THE PHYSICS of TIMLESSNESS Dr

Cosmos and History: The Journal of Natural and Social Philosophy, vol. 14, no. 2, 2018 THE PHYSICS OF TIMLESSNESS Dr. Varanasi Ramabrahmam ABSTRACT: The nature of time is yet to be fully grasped and finally agreed upon among physicists, philosophers, psychologists and scholars from various disciplines. Present paper takes clue from the known assumptions of time as - movement, change, becoming - and the nature of time will be thoroughly discussed. The real and unreal existences of time will be pointed out and presented. The complex number notation of nature of time will be put forward. Natural scientific systems and various cosmic processes will be identified as constructing physical form of time and the physical existence of time will be designed. The finite and infinite forms of physical time and classical, quantum and cosmic times will be delineated and their mathematical constructions and loci will be narrated. Thus the physics behind time-construction, time creation and time-measurement will be given. Based on these developments the physics of Timelessness will be developed and presented. KEYWORDS: physical time, psychological time, finite and infinite times, scalar and vector times, Classical, quantum and cosmic times, timelessness, movement, change, becoming INTRODUCTION: “Our present picture of physical reality, particularly in relation to the nature of time, is due for a grand shake-up—even greater, perhaps, than that which has already been provided by present-day relativity and quantum mechanics” [1]. Time is considered as www.cosmosandhistory.org 1 COSMOS AND HISTORY 2 one of the fundamental quantities in physics. Second, which is the duration of 9,192,631,770 cesium-133 atomic oscillations, is the unit. -

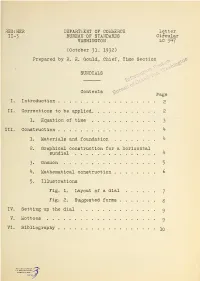

SUNDIALS \0> E O> Contents Page

REG: HER DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE Letter 1 1-3 BUREAU OF STANDARDS Circular WASHINGTON LC 3^7 (October Jl., 1932) Prepared by R. E. Gould, Chief, Time Section ^ . fA SUNDIALS \0> e o> Contents Page I. Introduction „ 2 II. Corrections to be applied 2 1. Equation of time 3 III. Construction 4 1. Materials and foundation 4 2. Graphical construction for a horizontal sundial 4 3. Gnomon . 5 4. Mathematical construction ........ 6 5,. Illustrations Fig. 1. Layout of a dial 7 Fig. 2. Suggested forms g IV. Setting up the dial 9 V. Mottoes q VI. Bibliography -10 . , 2 I. Introduction One of the earliest methods of determining time was by observing the position of the shadow cast by an object placed in the sunshine. As the day advances the shadow changes and its position at any instant gives an indication of the time. The relative length of the shadow at midday can also be used to indicate the season of the year. It is thought that one of the purposes of the great pyramids of Egypt was to indicate the time of day and the progress of the seasons. Although the origin of the sundial is very obscure, it is known to have been used in very early times in ancient Babylonia. One of the earliest recorded is the Dial of Ahaz 0th Century, B. C. mentioned in the Bible, II Kings XX: 0-11. , The Greeks used sundials in the 4th Century B. C. and one was set up in Rome in 233 B. C. Today sundials are used largely for decorative purposes in gardens or on lawns, and many inquiries have reached the Bureau of Standards regarding the construction and erection of such dials. -

Solar Panels and Optimization Introduction

Solar Panels and Optimization Due Thu, Nov. 2 2017 Image of the Sun. The image was taken from the astrophysics department at Stanford University. Introduction In this lab you will analyze how the efficiency of a solar panel depends on the season and its orientation. The solar radiation falling on a tilted plane (such as a solar panel) depends on numerous factors: the orientation of the plane, the time of the day, the season, the weather, etc. In the next few sections you will learn more about how this affects the power we can receive from solar panels. Figure 1: Sketch shows the Earth orbiting the Sun and the position of the Earth during different seasons. Figure 2: The angle s at the equator. The angle s is measured between the sun ray and the plane of the equator at noon. This implies that at summer solstice s = 23◦, at winter solstice s = −23◦ and the vernal/autumnal equinox s = 0◦. The Earth and the Sun The Earth's orbit about the Sun is almost circular so for this lab we will assume that the distance to the Sun is constant. However, the axis of the Earth is tilted relative to the plane in which the Earth moves around the Sun. The angle between the axis and a normal to this plane is roughly 23◦. As indicated in Figure 1, the north pole points away from the Sun during the northern hemisphere winter, and points toward the Sun during the northern hemisphere summer. Now let us imagine that we stand on the equator. -

Special Commission on Commonwealth's Time Zone Report

Report of the Special Commission on the Commonwealth’s Time Zone November 1, 2017 1 Contents Executive Summary ...................................................................................................3 Purpose of the Commission .......................................................................................6 Structure of the Commission .....................................................................................6 Background ................................................................................................................8 Findings ....................................................................................................................12 Economic Development: Commerce and Trade ...................................................12 Labor and Workforce ............................................................................................14 Public Health .........................................................................................................15 Energy ...................................................................................................................16 Crime and Criminal Justice...................................................................................18 Transportation .......................................................................................................19 Broadcasting .........................................................................................................20 Education and School Start-Times .......................................................................21 -

HUNTING and TRAPPING REGULATIONS Teal (Early Season) 5-20 Sep 2020 (All Zones) 6 18

Waterfowl Dates and Information 2020-2021 Illinois Digest of SPECIES DATES (INCLUSIVE) AND ZONES HOURS DAILY LIMIT POSSESSION LIMIT HUNTING AND TRAPPING REGULATIONS Teal (early season) 5-20 Sep 2020 (all zones) 6 18 Rail (Sora and Virginia only) 5 Sep - 13 Nov 2020 (all zones) Sunrise to Sunset 25 75 Deer & Turkey Season Dates and Limits Snipe (Wilson’s snipe) 5 Sep - 20 Dec 2020 (all zones) 8 24 SEASON DATES (INCLUSIVE) HOURS LIMIT 17 Oct - 15 Dec 2020 (North) Archery Deer (Counties with a firearm 1 Oct–19 Nov and 23 Nov–2 Dec and 7 Dec 2020–17 Jan 2021 One deer per archery permit 24 Oct - 22 Dec 2020 (Central) season and west of Route 47 in Kane County) Ducks (but see Scaup below) 6 18 Archery Deer (Cook, DuPage, Lake 14 Nov 2020 - 12 Jan 2021 (South-central) 1 Oct 2020–17 Jan 2021 One deer per archery permit 26 Nov 2020 - 24 Jan 2021 (South) and Kane [east of route 47] Counties) Firearm Deer 20-22 Nov and Mergansers Same as ducks 5 15 One deer per firearm permit (Shotgun, Muzzleloader, Handgun) 3-6 Dec 2020 1/2 hour Coots Same as ducks 15 45 before sunrise Muzzleloader-only Deer 11-13 Dec 2020 17 Oct - 30 Nov and 1 - 15 Dec (North) First Segment: First Segment: to 1/2 hour One deer per muzzleloader permit after sunset 24 Oct - 7 Dec and 8 - 22 Dec (Central) 2/day 6 31 Dec 2020–3 Jan 2021 and Scaup (Bluebills) Special CWD Deer One deer per valid permit 14 Nov - 28 Dec and 29 Dec - 12 Jan 2021 (SC) Second Segment: Second Segment: 15-17 Jan 2021 26 Nov - 9 Jan 2021 and 10 - 24 Jan (South) 1/day 3 Late Winter Antlerless-only Deer 31 Dec 2020–3 Jan 2021 and One antlerless deer per permit 1-15 Sep 2020 (North and Central) 5 15 (Shotgun, Muzzleloader, Handgun) 15-17 Jan 2021 Canada Geese (early season) 1-15 Sep 2020 (South-central and South) 2 6 Youth Firearm Deer 10-12 Oct 2020 One deer 1/2 hour before 17 Oct 2020 - 14 Jan 2021 (North) 1/2 hour before One tom, jake or bearded hen per permit, sunrise to sunset Youth Turkey (1 permit per year) 27-28 Mar and 3-4 Apr 2021 24 Oct - 1 Nov 2020 and sunrise to 1 p.m.