Cornwall Farmstead Assessment Framework Cornwall Historic Farmsteads Guidance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Notice of Poll and Situation of Polling Stations

NOTICE OF POLL AND SITUATION OF POLLING STATIONS CORNWALL COUNCIL VOTING AREA Referendum on the United Kingdom's membership of the European Union 1. A referendum is to be held on THURSDAY, 23 JUNE 2016 to decide on the question below : Should the United Kingdom remain a member of the European Union or leave the European Union? 2. The hours of poll will be from 7am to 10pm. 3. The situation of polling stations and the descriptions of persons entitled to vote thereat are as follows : No. of Polling Station Situation of Polling Station(s) Description of Persons entitled to vote 301 STATION 2 (AAA1) 1 - 958 CHURCH OF JESUS CHRIST OF LATTER-DAY SAINTS KINGFISHER DRIVE PL25 3BG 301/1 STATION 1 (AAM4) 1 - 212 THE CHURCH OF JESUS CHRIST OF LATTER-DAY SAINTS KINGFISHER DRIVE PL25 3BG 302 CUDDRA W I HALL (AAA2) 1 - 430 BUCKLERS LANE HOLMBUSH ST AUSTELL PL25 3HQ 303 BETHEL METHODIST CHURCH (AAB1) 1 - 1,008 BROCKSTONE ROAD ST AUSTELL PL25 3DW 304 BISHOP BRONESCOMBE SCHOOL (AAB2) 1 - 879 BOSCOPPA ROAD ST AUSTELL PL25 3DT KATE KENNALLY Dated: WEDNESDAY, 01 JUNE, 2016 COUNTING OFFICER Printed and Published by the COUNTING OFFICER ELECTORAL SERVICES, ST AUSTELL ONE STOP SHOP, 39 PENWINNICK ROAD, ST AUSTELL, PL25 5DR No. of Polling Station Situation of Polling Station(s) Description of Persons entitled to vote 305 SANDY HILL ACADEMY (AAB3) 1 - 1,639 SANDY HILL ST AUSTELL PL25 3AW 306 STATION 2 (AAG1) 1 - 1,035 THE COMMITTEE ROOM COUNCIL OFFICES PENWINNICK ROAD PL25 5DR 306/1 STATION 1 (APL3) 1 - 73 THE COMMITTEE ROOM CORNWALL COUNCIL OFFICES PENWINNICK -

CORNWALL Extracted from the Database of the Milestone Society

Entries in red - require a photograph CORNWALL Extracted from the database of the Milestone Society National ID Grid Reference Road No Parish Location Position CW_BFST16 SS 26245 16619 A39 MORWENSTOW Woolley, just S of Bradworthy turn low down on verge between two turns of staggered crossroads CW_BFST17 SS 25545 15308 A39 MORWENSTOW Crimp just S of staggered crossroads, against a low Cornish hedge CW_BFST18 SS 25687 13762 A39 KILKHAMPTON N of Stursdon Cross set back against Cornish hedge CW_BFST19 SS 26016 12222 A39 KILKHAMPTON Taylors Cross, N of Kilkhampton in lay-by in front of bungalow CW_BFST20 SS 25072 10944 A39 KILKHAMPTON just S of 30mph sign in bank, in front of modern house CW_BFST21 SS 24287 09609 A39 KILKHAMPTON Barnacott, lay-by (the old road) leaning to left at 45 degrees CW_BFST22 SS 23641 08203 UC road STRATTON Bush, cutting on old road over Hunthill set into bank on climb CW_BLBM02 SX 10301 70462 A30 CARDINHAM Cardinham Downs, Blisland jct, eastbound carriageway on the verge CW_BMBL02 SX 09143 69785 UC road HELLAND Racecourse Downs, S of Norton Cottage drive on opp side on bank CW_BMBL03 SX 08838 71505 UC road HELLAND Coldrenick, on bank in front of ditch difficult to read, no paint CW_BMBL04 SX 08963 72960 UC road BLISLAND opp. Tresarrett hamlet sign against bank. Covered in ivy (2003) CW_BMCM03 SX 04657 70474 B3266 EGLOSHAYLE 100m N of Higher Lodge on bend, in bank CW_BMCM04 SX 05520 71655 B3266 ST MABYN Hellandbridge turning on the verge by sign CW_BMCM06 SX 06595 74538 B3266 ST TUDY 210 m SW of Bravery on the verge CW_BMCM06b SX 06478 74707 UC road ST TUDY Tresquare, 220m W of Bravery, on climb, S of bend and T junction on the verge CW_BMCM07 SX 0727 7592 B3266 ST TUDY on crossroads near Tregooden; 400m NE of Tregooden opp. -

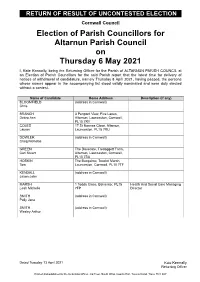

Election of Parish Councillors for Altarnun Parish Council on Thursday 6 May 2021

RETURN OF RESULT OF UNCONTESTED ELECTION Cornwall Council Election of Parish Councillors for Altarnun Parish Council on Thursday 6 May 2021 I, Kate Kennally, being the Returning Officer for the Parish of ALTARNUN PARISH COUNCIL at an Election of Parish Councillors for the said Parish report that the latest time for delivery of notices of withdrawal of candidature, namely Thursday 8 April 2021, having passed, the persons whose names appear in the accompanying list stood validly nominated and were duly elected without a contest. Name of Candidate Home Address Description (if any) BLOOMFIELD (address in Cornwall) Chris BRANCH 3 Penpont View, Five Lanes, Debra Ann Altarnun, Launceston, Cornwall, PL15 7RY COLES 17 St Nonnas Close, Altarnun, Lauren Launceston, PL15 7RU DOWLER (address in Cornwall) Craig Nicholas GREEN The Dovecote, Tredoggett Farm, Carl Stuart Altarnun, Launceston, Cornwall, PL15 7SA HOSKIN The Bungalow, Trewint Marsh, Tom Launceston, Cornwall, PL15 7TF KENDALL (address in Cornwall) Jason John MARSH 1 Todda Close, Bolventor, PL15 Health And Social Care Managing Leah Michelle 7FP Director SMITH (address in Cornwall) Polly Jane SMITH (address in Cornwall) Wesley Arthur Dated Tuesday 13 April 2021 Kate Kennally Returning Officer Printed and published by the Returning Officer, 3rd Floor, South Wing, County Hall, Treyew Road, Truro, TR1 3AY RETURN OF RESULT OF UNCONTESTED ELECTION Cornwall Council Election of Parish Councillors for Antony Parish Council on Thursday 6 May 2021 I, Kate Kennally, being the Returning Officer for the Parish of ANTONY PARISH COUNCIL at an Election of Parish Councillors for the said Parish report that the latest time for delivery of notices of withdrawal of candidature, namely Thursday 8 April 2021, having passed, the persons whose names appear in the accompanying list stood validly nominated and were duly elected without a contest. -

Update on Cornish Foodbanks 30Th July 2021

FOODBANK UPDATE Update on Cornish Foodbanks 30th July 2021 Foodbanks across Cornwall need supplies of all tinned, dried or long-life food items - with a typical food parcel including: Breakfast cereal, long-life milk, soup, pasta, rice, pasta sauce, tinned beans, tinned meat, tinned vegetables, tinned fruit, tinned puddings, tea or coffee, sugar, biscuits and snacks. Many of the foodbanks also collect: Baby food, baby milk, disposable nappies, washing up liquid, Washing Powder, soap, Dry Dog Food, canned Dog Food and canned Cat Food. The way each Cornish foodbank runs is very unique, depending on volunteers, the building they operate, their capacity, their community and their opening times. If you would like to donate and support your local foodbank, we have included links to some of the foodbanks below; we have purposely included references to their Facebook pages where possible. If you could help your foodbank by looking at their Facebook posts before contacting them, that would be super helpful as these often have the most up to date answers to many queries. Facebook posts often also have details of any financial donation appeals individual foodbanks are running, or for some foodbanks with websites, there is often a direct link to donate money to them. PLEASE NOTE: The mission of Foodbanks is to give out food parcels to people in need. Customers can access foodbanks with a food voucher. Many of the Foodbanks are now operating an e-voucher system but please check how your local Foodbank is operating. There are many wonderful community food projects that people without Foodbank vouchers can access and, in many cases, this may be more appropriate. -

Allocation of Schools Per Case Work Officer

Information Classification: PUBLIC Statutory Special Educational Needs | Find Your Case Work Officer This list details the schools and postcodes that each case work officer is responsible for. West Cornwall Rupert Lawler: Area Casework Officer (West) email: [email protected] CWO: Bridget Bingley email: [email protected] Area Postcodes TR17, TR18, TR20 Early years Allocated by home address Independent special school (ISP) / out of Allocated by home address county Post 16 Allocated by home address Special school Curnow (Upper Y7 – 11) Allocated by home address, or if dual registered ACE Academy allocated by mainstream school base EHE Allocated by home address Allocated by home address if single registered and by APAs mainstream school base if dual registered Secondary schools Primary schools Humphry Davy Alverton, Germoe, Gulval, Heamoor, Ludgvan, Marazion, Mousehole, Newlyn, Pensans, St Hilary, St Mounts Bay Academy Maddern’s, St Mary’s CE, St Mary’s RC, Trythall CWO: Jenni Trewhella email: [email protected] Area Postcodes TR12, TR13 Early years Allocated by home address Independent special school (ISP) / out of Allocated by home address county Post 16 Allocated by home address Information Classification: PUBLIC Special school Curnow (Lower Y-1 – 6 & Post 16 Y12-14) Allocated by home address or if dual registered ACE Academy allocated by mainstream school base EHE Allocated by home address Allocated by home address if single registered and by APAs mainstream school base if dual registered Secondary -

Edited by IJ Bennallick & DA Pearman

BOTANICAL CORNWALL 2010 No. 14 Edited by I.J. Bennallick & D.A. Pearman BOTANICAL CORNWALL No. 14 Edited by I.J.Bennallick & D.A.Pearman ISSN 1364 - 4335 © I.J. Bennallick & D.A. Pearman 2010 No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior permission of the copyright holder. Published by - the Environmental Records Centre for Cornwall & the Isles of Scilly (ERCCIS) based at the- Cornwall Wildlife Trust Five Acres, Allet, Truro, Cornwall, TR4 9DJ Tel: (01872) 273939 Fax: (01872) 225476 Website: www.erccis.co.uk and www.cornwallwildlifetrust.org.uk Cover photo: Perennial Centaury Centaurium scilloides at Gwennap Head, 2010. © I J Bennallick 2 Contents Introduction - I. J. Bennallick & D. A. Pearman 4 A new dandelion - Taraxacum ronae - and its distribution in Cornwall - L. J. Margetts 5 Recording in Cornwall 2006 to 2009 – C. N. French 9 Fitch‟s Illustrations of the British Flora – C. N. French 15 Important Plant Areas – C. N. French 17 The decline of Illecebrum verticillatum – D. A. Pearman 22 Bryological Field Meetings 2006 – 2007 – N. de Sausmarez 29 Centaurium scilloides, Juncus subnodulosus and Phegopteris connectilis rediscovered in Cornwall after many years – I. J. Bennallick 36 Plant records for Cornwall up to September 2009 – I. J. Bennallick 43 Plant records and update from the Isles of Scilly 2006 – 2009 – R. E. Parslow 93 3 Introduction We can only apologise for the very long gestation of this number. There is so much going on in the Cornwall botanical world – a New Red Data Book, an imminent Fern Atlas, plans for a new Flora and a Rare Plant Register, plus masses of fieldwork, most notably for Natural England for rare plants on SSSIs, that somehow this publication has kept on being put back as other more urgent tasks vie for precedence. -

December 2018 Contents

December 2018 Contents Message from Mrs Costello English Maths Science Art and Design Computing Design and Technology Geography History Foreign Languages Music Outdoor Learning Religious education Early Years Foundation Stage Physical Education and Sport Nativity Residential Inclusion Friends of Connor Downs Academy Page 2 A message from Mrs Costello Dear parents and carers, I hope that you enjoy reading the autumn term newsletter as much as I have. It has been wonderful to see how many exciting activities have been taking place across our academy involving children of all ages. As usual, a highlight for me this term has been the appointment of our prefect and Head prefects. I was very proud to hand out their badges with Mrs Eddy earlier in the term. We have an outstanding team of prefects who are working very hard to make our school a friendly place for all children. They are particularly keen to support our youngest children in their first experiences of school-life and to support staff at break times. I also enjoyed seeing so many of our children enjoying their music performances and I hope that you all had the opportunity to watch them perform too. We have so many talented children, from singers, dancers and actors to engineers of the future. It was a pleasure to see them having fun on stage and working together on their performances as a team. The remainder of this newsletter will demonstrate just how much effort all of the staff here put into providing a curriculum that is full of diverse knowledge, understanding and skills. -

Abg Partners

ABG PARTNERS CORNWALL FESTIVAL OF BUSINESS 2020 EQUIP YOUR SKILLS HUB WEBINARS BUSINESS WITH THE 7 SKILLS EVERY NEW SKILLS FOR FOOD & DRINK BUSINESS NEEDS A NEW WAY OF 2 Nov / 1 - 1.30pm WORKING HOW A SKILLS REVIEW CAN HELP YOUR BUSINESS THRIVE 3 Nov / 1 - 1.30pm Q&A WITH LOCAL SKILLS EXPERTS: ADAPT TO SURVIVE AND THRIVE 6 Nov / 1 - 2pm For more information visit www.ciosskillshub.com WHERE TO NEXT? WESTERN MORNING NEWS Thursday, October 22, 2020 ANNUAL BUsiness GUIDE 2020 3 Welcome from Bill Martin, Marketplace Publisher, Reach PLC Region’s unique opportunity £1 WEDNESDAY, AUGUST 5, 2020 TRUSTED NEWS SINCE 1860 DEVON £1 WEDNESDAY, OCTOBER 7, 2020 TRUSTED NEWS SINCE 1860 CORNWALL £1 MONDAY, MARCH 9, 2020 TRUSTED NEWS SINCE 1860 CORNWALL £1 MONDAY, JULY 13, 2020 TRUSTED NEWS SINCE 1860 DEVON > The Goonhilly Earth Station in Cornwall will get > A pledge by Prime Minister funding for a space institute Boris Johnson to invest in and manufacturing facility offshore wind farms has been BID TO PULL UP A CHAIR FOR welcomed by those behind ambitious plans for a floating turbine array in the Celtic Sea HELP FLYBE A £500 CURRYS THE PERFECT VIEW As tens of millions WORKERS of pounds are pumped WINPC WORLD VOUCHER PAGE 15 into West building projects DETAILS & TOKEn – pAGE 7 – from space engineering and mining to leisure centres and Bids in for cultural venues – it seems that finally... new school Time to deliver for in Cornwall WO separate bids have been submitted to the Gov- Ternment to open a new secondary school in Cornwall. -

Cornwall Council

Cornwall Council Preliminary Flood Risk Assessment ANNEX 5 – Chronology of Major Flood Events in Cornwall June 2011 1800 – 1899 A storm caused coastal flooding affecting a number of communities along the south coast on 19-20 January 1817. Polperro harbour was destroyed by this storm and Looe was badly damaged. Truro suffered from numerous flooding events during the 1800s (1811, 1815, 1818, 1838, 1841, 1844, 1846, 1848 (twice), 1869, 1875, 1880, 1882 (twice), 1885, 1894 and 1899). These were usually associated with high river flows coinciding with high tides. Known as the Great Flood of 16 July 1847, due to an intense rainstorm event on Davidstow Moor water collected in the valley and forced a passage of water down the Camel and Inney. Bodmin - Dunmere Valley and the whole area below Dunmere Hill was flooded by the River Camel. Dunmere Bridge was washed away as was the new 40 feet (12 m) high railway bridge. At St. Breward, bridges from Gam Bridge to Dunmere were washed away by a wall of water 12 to 18 feet (3.5-5.5 m) above normal along the River Camel. The devastating floods that swept down from Davidstow Moor washed away all but two of the bridges along the River Camel - Wadebridge and Helland being the only survivors. Serious flooding occurred in Par and St Blazey in November 1852. November 1875 saw heavy rain resulting in serious flooding in Bude, Camelford, Polmorla, Hayle, St Just, Penzance and Truro. Extreme rainfall in October 1880 resulted in serious flooding in both Bodmin and Truro. High tides at the end of September and early October 1882 resulted in flooding in Boscastle, Truro, Wadebridge and Padstow. -

Planning Future Cornwall

Cornwall Local Development Framework Framweyth Omblegya Teythyek Kernow Planning Future Cornwall Growth Factors: Hayle & St Ives Community Network Area Version 2 February 2013 Growth Factors – Hayle & St Ives Community Network Area This ‘Profile’ brings together a range of key facts about the Hayle & St Ives Community Network Area that will act as an evidence base to help determine how much growth the area should accommodate over the next twenty years to maintain to enhance its viability and resilience. Each ‘Profile’ is split into three sections: Policy Objectives, Infrastructure & Environmental Considerations and Socio-Economic Considerations. Summaries have been provided to indicate what the key facts might mean in terms of the need for growth – and symbols have been used as follows to give a quick overview: Supports the case for future No conclusion reached/ Suggests concern over growth neutral factor/further future growth evidence required Hayle & St Ives Overview: The Hayle & St. Ives Community Network Area contains 5 parishes and a range of settlements. Hayle and St. Ives (including Carbis Bay) are the main settlements within this area, and act as the local service centres to the smaller settlements surrounding them. Larger villages in the area include Connor Downs and St. Erth whereas smaller villages include Carnhell Green, Gwinear, Gwithian, Halsetown, Lelant, Nancledra, Reawla and Towednack. This is a CNA encapsulating very diverse landscapes - the high moors of the west to the conservative, rich farmlands of the south-eastern part of the area. The Towans are part of the industrial, defence-related and settlement history of the whole area, related to Hayle as are the quays and causeways all round the estuary1. -

Penwith Introduc on 2019

26/04/2019 Introduction Introducon Penwith 2019 The Penwith locality stretches from St Ives on the North Coast to Marazion on the South Coast. The locality includes the towns of Penzance and Hayle and the Key Messages small rural town of St Just. West Cornwall Hospital in Penzance is a 8 GP pracces, 2 of which are dispensing satellite hospital, providing a 24-hour Urgent Care Centre, amongst other 65,170 residents are registered at the GP Pracces facilies. Addionally there is St Michael’s hospital, in Hayle, providing a range of Over 12,000 residents registered at Stennack Surgery specialist services. Obesity is the worst long term condion Edward Hain community hospital, is located in St Ives along with a minor injury 27.5% of paents are elderly unit at the Stennack Surgery. Currently 644 care home beds, 1,063 new units planned The main general hospital for Cornwall, Royal Cornwall Hospitals NHS Trust, Treliske, is based in Truro. 65,170 12.43% Registered Paents GP Pracces Paents Obese Name Address Town Postcode Status/Dispensing ALVERTON PRAC 7 ALVERTON TERRACE PENZANCE TR18 4JH Pracce - Non Disp BODRIGGY HEALTH CTR 60 QUEENSWAY HAYLE TR27 4PB Pracce - Non Disp CAPE CORNWALL SURGERY ST.JUST-IN-PENWITH PENZANCE TR19 7HX Pracce - Disp MARAZION SURGERY GWALLON LANE MARAZION TR17 0HW Pracce - Disp MORRAB SURGERY 2 MORRAB ROAD PENZANCE TR18 4EL Pracce - Non Disp 27.5% ROSMELLYN SURGERY ALVERTON TERRACE PENZANCE TR18 4JH Pracce - Non Disp 1,063 STENNACK SURGERY THE OLD STENNACK SCHOOL ST.IVES TR26 1RU Pracce - Non Disp Care Home Paents SUNNYSIDE SURGERY HAWKINS ROAD PENZANCE TR18 4LT Pracce - Non Disp Units Planned 65+ Introducon Populaon Elderly Populaon 1/1 26/04/2019 Population Populaon Penwith 2019 The latest figures (2017) show that the populaon for the Penwith Locality is 63,936, with a difference of almost 3,000 more female than male. -

Ref: LCAA1820

Ref: LCAA6774 £249,950 2 Treeve Court, Treeve Lane, Connor Downs, Hayle, Cornwall FREEHOLD A 4 bedroomed mid terrace of three barn conversion with front and rear gardens, very generous parking and garage close to Gwithian Beach, in a semi rural location but within walking distance of various facilities. A perfect family home specially adapted and extended for disabled living with a large ground floor bedroom and huge wet shower room which could simply revert to further living accommodation if required. 2 Ref: LCAA6774 SUMMARY OF ACCOMMODATION Ground Floor: porch, entrance hall, lounge, semi open-plan to a kitchen/dining room. Double bedroom, very large en-suite wet shower room with disabled facilities. First Floor: landing, 3 bedrooms, bathroom. Stairs to an attic room. Outside: front and rear lawned gardens, large deck, shed. Garage, extensive parking owned by this property. DESCRIPTION 2 Treeve Court is the middle of three in a terrace created from a barn which was converted around 15 years ago. The property enjoys a semi rural location just outside Connor Downs on the way to the beach at Gwithian. A long driveway approach leads past large grassed areas which are partly owned by 2 Treeve Court with the majority still owned and maintained by the original owner of the barns and he overlooks it from his nearby bungalow. The extensive car parking to the front is actually owned by 2 Treeve Court with the other properties having a car parking space each in front of the respective buildings, whilst all three have a garage in a block to the side of which are the individual LPG tanks, with number two’s being replaced in 2016.