A Biological Survey of the Southern Mount Lofty Ranges

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In This Issue Birds SA Aims To: • Promote the Conservation of a SPECIAL BUMPER CHRISTMAS Australian Birds and Their Habitats

Linking people with birds in South Australia The Birder No 240 November 2016 In this Issue Birds SA aims to: • Promote the conservation of A SPECIAL BUMPER CHRISTMAS Australian birds and their habitats. ISSUE — LOTS OF PHOTOS • Encourage interest in, and develop knowledge of, the birds of South Australia. PLEASE VOLUNTEER — THE BIRDS • Record the results of research into NEED YOUR HELP! all aspects of bird life. • Maintain a public fund called the A NATIONAL PARK IN THE “Birds SA Conservation Fund” for INTERNATIONAL BIRD SANCTUARY the specific purpose of supporting the Association’s environmental objectives. CO N T E N T S N.B. ‘THE BIRDER’ will not be President’s Message 3 published in February 2017. The Birds SA Notes & News 4 next issue of this newsletter will be The Laratinga Birdfair 8 distributed at the March General Kangaroos at Sandy Creek CP. 9 Meeting, on 31 March 2017. Return of the Adelaide Rosella 10 Giving them wings 11 Cover photo Past General Meetings 13 Emu, photographed by Barbara Bansemer in Future General Meetings 15 Brachina Gorge, Flinders Ranges, on 26th Past Excursions 16 October 2016. Future Excursions 23 Bird Records 25 New Members From the Library 28 We welcome 25 new members who have About our Association 30 recently joined the Association. Their names are listed on p29. Photos from Members 31 CENTRE INSERT: SAOA HISTORICAL SERIES No: 58, JOHN SUTTON’S OUTER HARBOR NOTES, PART 8 DIARY The following is a list of Birds SA activities for the next few months. Further details of all these activities can be found later in ‘The Birder’. -

The Role of Intense Nest Predation in the Decline of Scarlet Robins and Eastern Yellow Robins in Remnant Woodland Near Armidale, New South Wales

The role of intense nest predation in the decline of Scarlet Robins and Eastern Yellow Robins in remnant woodland near Armidale, New South Wales S. J. S. DEBDSI A study of open-nesting Eastern Yellow Robins Eopsaltria australis and Scarlet Robins Petroica multicolor, on the New England Tablelands of New South Wales in 2000-02, found Iow breeding success typical of eucalypt woodland birds. The role of intense nest predation in the loss of birds from woodland fragments was investigated by means of predator-exclusion cages at robin nests, culling of Pied Currawongs Strepera graculina, and monitoring of fledging and recruitment in the robins. Nest-cages significantly improved nest success (86% vs 20%) and fledging rate (1.6 vs 0.3 fledglings per attempt) for both robin species combined (n = 7 caged, 20 uncaged). For both robin species combined, culling of currawongs produced a twofold difference in nest success (33% vs 14%), a higher fledging rate (0.5 vs 0.3 per attempt), and a five-day difference in mean nest survival (18 vs 13 days) (n = 62 nests), although sample sizes for nests in the cull treatment (n = 18) were small and nest predation continued. Although the robin breeding population had not increased one year after the cull, the pool of Yellow Robin recruits in 2001-03, after enhanced fledging success, produced two emigrants to a patch where Yellow Robins had become extinct. Management to assist the conservation of open-nesting woodland birds should address control of currawongs. Key words: Woodland birds, Habitat fragmentation, Nest predation, Predator exclusion, Predator removal. -

New Operational Taxonomic Units of Enterocytozoon in Three Marsupial Species Yan Zhang1, Anson V

Zhang et al. Parasites & Vectors (2018) 11:371 https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-018-2954-x RESEARCH Open Access New operational taxonomic units of Enterocytozoon in three marsupial species Yan Zhang1, Anson V. Koehler1* , Tao Wang1, Shane R. Haydon2 and Robin B. Gasser1* Abstract Background: Enterocytozoon bieneusi is a microsporidian, commonly found in animals, including humans, in various countries. However, there is scant information about this microorganism in Australasia. In the present study, we conducted the first molecular epidemiological investigation of E. bieneusi in three species of marsupials (Macropus giganteus, Vombatus ursinus and Wallabia bicolor) living in the catchment regions which supply the city of Melbourne with drinking water. Methods: Genomic DNAs were extracted from 1365 individual faecal deposits from these marsupials, including common wombat (n = 315), eastern grey kangaroo (n = 647) and swamp wallaby (n = 403) from 11 catchment areas, and then individually tested using a nested PCR-based sequencing approach employing the internal transcribed spacer (ITS) and small subunit (SSU) of nuclear ribosomal DNA as genetic markers. Results: Enterocytozoon bieneusi was detected in 19 of the 1365 faecal samples (1.39%) from wombat (n =1), kangaroos (n = 13) and wallabies (n =5).TheanalysisofITS sequence data revealed a known (designated NCF2) and four new (MWC_m1 to MWC_m4) genotypes of E. bieneusi. Phylogenetic analysis of ITS sequence data sets showed that MWC_m1 (from wombat) clustered with NCF2, whereas genotypes MWC_m2 (kangaroo and wallaby), MWC_m3 (wallaby) and MWC_m4 (kangaroo) formed a new, divergent clade. Phylogenetic analysis of SSU sequence data revealed that genotypes MWC_m3 and MWC_m4 formed a clade that was distinct from E. -

Husbandry Guidelines for Common Ringtail Possums, Pseudocheirus Peregrinus Mammalia: Pseudocheiridae

32325/01 Casey Poolman E0190918 Husbandry guidelines for Common Ringtail Possums, Pseudocheirus peregrinus Mammalia: Pseudocheiridae Ault Ringtail Possum Image: Casey Poolman Author: Casey Poolman Date of preparation: 7/11/2017 Open Colleges, Course name and number: ACM30310 Certificate III in Captive Animals Trainer: Chris Hosking Husbandry guidelines for Pseudocheirus peregrinus 1 32325/01 Casey Poolman E0190918 Author contact details [email protected] Disclaimer Please note that these husbandry guidelines are student material, created as part of student assessment for Open Colleges ACM30310 Certificate III in Captive Animals. While care has been taken by students to compile accurate and complete material at the time of creation, all information contained should be interpreted with care. No responsibility is assumed for any loss or damage resulting from using these guidelines. Husbandry guidelines are evolving documents that need to be updated regularly as more information becomes available and industry knowledge about animal welfare and care is extended. Husbandry guidelines for Pseudocheirus peregrinus 2 32325/01 Casey Poolman E0190918 Workplace Health and Safety risks warning Ringtail Possums are not an aggressive possum and will mostly try to freeze or hide when handled, however they can and do bite, which can be deep and penetrating. When handling possums always be careful not to get bitten, do not put your hands around its mouth. You should always use two hands and be firm but gentle. Adult Ringtail Possums should be gripped by the back of the neck and around the shoulders with one hand and around the base of the tail with the other. This should allow you to control the animal without hurting it and reduces the risk of you being bitten or scratched. -

Platypus Collins, L.R

AUSTRALIAN MAMMALS BIOLOGY AND CAPTIVE MANAGEMENT Stephen Jackson © CSIRO 2003 All rights reserved. Except under the conditions described in the Australian Copyright Act 1968 and subsequent amendments, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, duplicating or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. Contact CSIRO PUBLISHING for all permission requests. National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Jackson, Stephen M. Australian mammals: Biology and captive management Bibliography. ISBN 0 643 06635 7. 1. Mammals – Australia. 2. Captive mammals. I. Title. 599.0994 Available from CSIRO PUBLISHING 150 Oxford Street (PO Box 1139) Collingwood VIC 3066 Australia Telephone: +61 3 9662 7666 Local call: 1300 788 000 (Australia only) Fax: +61 3 9662 7555 Email: [email protected] Web site: www.publish.csiro.au Cover photos courtesy Stephen Jackson, Esther Beaton and Nick Alexander Set in Minion and Optima Cover and text design by James Kelly Typeset by Desktop Concepts Pty Ltd Printed in Australia by Ligare REFERENCES reserved. Chapter 1 – Platypus Collins, L.R. (1973) Monotremes and Marsupials: A Reference for Zoological Institutions. Smithsonian Institution Press, rights Austin, M.A. (1997) A Practical Guide to the Successful Washington. All Handrearing of Tasmanian Marsupials. Regal Publications, Collins, G.H., Whittington, R.J. & Canfield, P.J. (1986) Melbourne. Theileria ornithorhynchi Mackerras, 1959 in the platypus, 2003. Beaven, M. (1997) Hand rearing of a juvenile platypus. Ornithorhynchus anatinus (Shaw). Journal of Wildlife Proceedings of the ASZK/ARAZPA Conference. 16–20 March. -

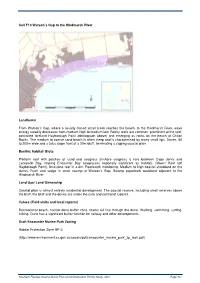

Cell F10 Watson's Gap to the Hindmarsh River L Andforms From

Cell F10 Watson’s Gap to the Hindmarsh River L andforms From Watson’s Gap, where a usually closed small creek reaches the b each, to the H indmarsh R iv er, wav e energ y steadily decreases from medium hig h to medium low. R ock y reefs are common, prominent at the reef- controlled foreland H ayb oroug h P oint (photog raph ab ov e) and emerg ing as rock s on the b each at C hiton R ock s. T he medium to coarse sand b each is often steep and is characterised b y many small rips. D unes, 5 0 to 2 0 0 m wide and a talus slope front of a 2 0 m b luff, terminating a sloping coastal plain. B enthic Hab itat/ B iota P latform reef with patches of sand and seag rass (inshore seag rass is rare b etween C ape J erv is and L acepede B ay, mak ing E ncounter B ay seag rasses reg ionally sig nificant as hab itat). O liv ers R eef (off H ayb oroug h P oint), limestone reef in 4 -6 m. R eefwatch monitoring . M edium to hig h coastal shrub land on the dunes. R ush and sedg e in small swamp at Watson’s Gap. S wamp paperb ark woodland adjacent to the H indmarsh R iv er. L and U se/ L and O w nership C oastal plain is almost entirely residential dev elopment. T he coastal reserv e, including small reserv es ab ov e the b luff, the b luff and the dunes are under the care and control of C ouncil. -

The Mahogany Glider

ISSUE #3 – WINTER 2019 THE MAHOGANY GLIDER The mahogany glider is one of Australia’s most threatened mammals and Queensland’s only listed endangered glider species. Named for its mahogany-brown belly, this graceful glider has two folds of skin, called a patagium, which stretch A mahogany glider, Petaurus gracilis, venturing out at the Hidden Vale Wildlife Centre. between the front and rear legs. These act as a ‘parachute’ enabling the animal to glide distances of and the Hidden Vale Wildlife Centre is manipulate their patagium in order to 30 metres in open woodland habitat. one of just a few locations authorised land safely. Their long tail is used for mid-air for breeding. Breeding is undertaken The Centre recently received funding stabilisation. as an insurance against extinction. to purchase additional structures The Centre regularly exchanges They look similar to sugar or squirrel including climbing ropes and nets, gliders with other authorised gliders, however mahogany gliders ladders and ‘unstable’ branches to locations to ensure genetic are much larger. They are nocturnal, simulate the movement of small trees. diversity in captive populations. elusive and silent, making research on We are also planning to introduce free-ranging animals very difficult. We encourage our mahogany gliders a range of glider-suitable feeding to develop and display their normal Mahogany gliders appear to be enrichment, such as whole fruits, range of behaviours. That is why we monogamous and will actively mark puzzle-feeders, or feed in a hanging have set up one half of their enclosure and defend their territory. They use log. We hope that our gliders will not with climbing structures in the form hollows in large eucalypt trees, lined only breed well, but will also become of ‘stable’ branches, while the right with a thick mat of leaves, as dens. -

Rodondo Island

BIODIVERSITY & OIL SPILL RESPONSE SURVEY January 2015 NATURE CONSERVATION REPORT SERIES 15/04 RODONDO ISLAND BASS STRAIT NATURAL AND CULTURAL HERITAGE DIVISION DEPARTMENT OF PRIMARY INDUSTRIES, PARKS, WATER AND ENVIRONMENT RODONDO ISLAND – Oil Spill & Biodiversity Survey, January 2015 RODONDO ISLAND BASS STRAIT Biodiversity & Oil Spill Response Survey, January 2015 NATURE CONSERVATION REPORT SERIES 15/04 Natural and Cultural Heritage Division, DPIPWE, Tasmania. © Department of Primary Industries, Parks, Water and Environment ISBN: 978-1-74380-006-5 (Electronic publication only) ISSN: 1838-7403 Cite as: Carlyon, K., Visoiu, M., Hawkins, C., Richards, K. and Alderman, R. (2015) Rodondo Island, Bass Strait: Biodiversity & Oil Spill Response Survey, January 2015. Natural and Cultural Heritage Division, DPIPWE, Hobart. Nature Conservation Report Series 15/04. Main cover photo: Micah Visoiu Inside cover: Clare Hawkins Unless otherwise credited, the copyright of all images remains with the Department of Primary Industries, Parks, Water and Environment. This work is copyright. It may be reproduced for study, research or training purposes subject to an acknowledgement of the source and no commercial use or sale. Requests and enquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be addressed to the Branch Manager, Wildlife Management Branch, DPIPWE. Page | 2 RODONDO ISLAND – Oil Spill & Biodiversity Survey, January 2015 SUMMARY Rodondo Island was surveyed in January 2015 by staff from the Natural and Cultural Heritage Division of the Department of Primary Industries, Parks, Water and Environment (DPIPWE) to evaluate potential response and mitigation options should an oil spill occur in the region that had the potential to impact on the island’s natural values. Spatial information relevant to species that may be vulnerable in the event of an oil spill in the area has been added to the Australian Maritime Safety Authority’s Oil Spill Response Atlas and all species records added to the DPIPWE Natural Values Atlas. -

DC MOUNT BARKER HERITAGE SURVEY Part 1: Heritage Analysis, Zones & Inventory

The District Council of Mount Barker DC MOUNT BARKER HERITAGE SURVEY Part 1: Heritage Analysis, Zones & Inventory Heritage Online Anna Pope & Claire Booth DC MOUNT BARKER HERITAGE SURVEY (2004) Part 1 Heritage Analysis, Zones & Inventory Part 2 State Heritage Recommendations Part 3 Local Heritage Recommendations: Biggs Flat to Hahndorf Part 4 Local Heritage Recommendations: Harrogate to Meadows Part 5 Local Heritage Recommendations: Mount Barker to Wistow Commissioned by: The District Council of Mount Barker Authors: Anna Pope Claire Booth Front cover photographs (all taken 2003-04): View towards Mount Barker summit from the cemetery of St James’ Anglican Church, Blakiston Bremer mine - proposed Callington State Heritage Area Callington Bridge - proposed Callington State Heritage Area Paechtown 2003 - proposed Historic (Conservation) Zone Macclesfield bridge from Catholic precinct - proposed Macclesfield State Heritage Area Schneemilch barn - Hahndorf State Heritage Area Mount Barker Heritage Survey (2004) ~ Part 1 Contents PART 1 ~ Summary Of Recommendations & Inventory CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION............................................................................................................1 1.1 Background............................................................................................................1 1.2 Objectives ..............................................................................................................1 1.3 Study Area .............................................................................................................1 -

National Parks and Wildlife Act 1972.PDF

Version: 1.7.2015 South Australia National Parks and Wildlife Act 1972 An Act to provide for the establishment and management of reserves for public benefit and enjoyment; to provide for the conservation of wildlife in a natural environment; and for other purposes. Contents Part 1—Preliminary 1 Short title 5 Interpretation Part 2—Administration Division 1—General administrative powers 6 Constitution of Minister as a corporation sole 9 Power of acquisition 10 Research and investigations 11 Wildlife Conservation Fund 12 Delegation 13 Information to be included in annual report 14 Minister not to administer this Act Division 2—The Parks and Wilderness Council 15 Establishment and membership of Council 16 Terms and conditions of membership 17 Remuneration 18 Vacancies or defects in appointment of members 19 Direction and control of Minister 19A Proceedings of Council 19B Conflict of interest under Public Sector (Honesty and Accountability) Act 19C Functions of Council 19D Annual report Division 3—Appointment and powers of wardens 20 Appointment of wardens 21 Assistance to warden 22 Powers of wardens 23 Forfeiture 24 Hindering of wardens etc 24A Offences by wardens etc 25 Power of arrest 26 False representation [3.7.2015] This version is not published under the Legislation Revision and Publication Act 2002 1 National Parks and Wildlife Act 1972—1.7.2015 Contents Part 3—Reserves and sanctuaries Division 1—National parks 27 Constitution of national parks by statute 28 Constitution of national parks by proclamation 28A Certain co-managed national -

The Western Ringtail Possum (Pseudocheirus Occidentalis)

A major road and an artificial waterway are barriers to the rapidly declining western ringtail possum, Pseudocheirus occidentalis Kaori Yokochi BSc. (Hons.) This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The University of Western Australia School of Animal Biology Faculty of Science October 2015 Abstract Roads are known to pose negative impacts on wildlife by causing direct mortality, habitat destruction and habitat fragmentation. Other kinds of artificial linear structures, such as railways, powerline corridors and artificial waterways, have the potential to cause similar negative impacts. However, their impacts have been rarely studied, especially on arboreal species even though these animals are thought to be highly vulnerable to the effects of habitat fragmentation due to their fidelity to canopies. In this thesis, I studied the effects of a major road and an artificial waterway on movements and genetics of an endangered arboreal species, the western ringtail possum (Pseudocheirus occidentalis). Despite their endangered status and recent dramatic decline, not a lot is known about this species mainly because of the difficulties in capturing them. Using a specially designed dart gun, I captured and radio tracked possums over three consecutive years to study their movement and survival along Caves Road and an artificial waterway near Busselton, Western Australia. I studied the home ranges, dispersal pattern, genetic diversity and survival, and performed population viability analyses on a population with one of the highest known densities of P. occidentalis. I also carried out simulations to investigate the consequences of removing the main causes of mortality in radio collared adults, fox predation and road mortality, in order to identify effective management options. -

FNCV Register of Photos

FNCV Register of photos - natural history (FNCVSlideReg is in Library computer: My computer - Local Disc C - Documents and settings - Library) [Square brackets] - added or updated name Slide number Title Place Date Source Plants SN001-1 Banksia marginata Grampians 1974 001-2 Xanthorrhoea australis Labertouche 17 Nov 1974 001-3 Xanthorrhoea australis Anglesea Oct 1983 001-4 Regeneration after bushfire Anglesea Oct 1983 001-5 Grevillea alpina Bendigo 1975 001-6 Glossodia major / Grevillea alpina Maryborough 19 Oct 1974 001-7 Discarded - out of focus 001-8 [Asteraceae] Anglesea Oct 1983 001-9 Bulbine bulbosa Don Lyndon 001-10 Senecio elegans Don Lyndon 001-11 Scaevola ramosissima (Hairy fan-flower) Don Lyndon 001-12 Brunonia australis (Blue pincushion) Don Lyndon 001-13 Correa alba Don Lyndon 001-14 Correa alba Don Lyndon 001-15 Calocephalus brownii (Cushion bush) Don Lyndon 001-16 Rhagodia baccata [candolleana] (Seaberry saltbush) Don Lyndon 001-17 Lythrum salicaria (Purple loosestrife) Don Lyndon 001-18 Carpobrotus sp. (Pigface in the sun) Don Lyndon 001-19 Rhagodia baccata [candolleana] Inverloch Don Lyndon 001-20 Epacris impressa Don Lyndon 001-21 Leucopogon virgatus (Beard-heath) Don Lyndon 001-22 Stackhousia monogyna (Candles) Don Lyndon 001-23 Correa reflexa (yellow) Don Lyndon 001-24 Prostanthera sp. Don Lyndon Fungi 002-1 Stinkhorn fungus Aseroe rubra Buckety Plains 30/12/1974 Margarey Lester 002-2 Fungi collection: Botany Group excursion Dom Dom Saddle 28 May 1988 002-3 Aleuria aurantia Aug 1966 R&M Jennings Bairnsdale FNC 002-4