The Sinagua and Aggregation: an Interdisciplinary Approach to Cultural Development

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Southern Sinagua Sites Tour: Montezuma Castle, Montezuma

Information as of Old Pueblo Archaeology Center Presents: March 4, 2021 99 a.m.-5:30a.m.-5:30 p.m.p.m. SouthernSouthern SinaguaSinagua SitesSites Tour:Tour: MayMay 8,8, 20212021 MontezumaMontezuma Castle,Castle, SaturdaySaturday MontezumaMontezuma Well,Well, andand TuzigootTuzigoot $30 donation ($24 for members of Old Pueblo Archaeology Center or Friends of Pueblo Grande Museum) Donations are due 10 days after reservation request or by 5 p.m. Wednesday May 8, whichever is earlier. SEE NEXT PAGES FOR DETAILS. National Park Service photographs: Upper, Tuzigoot Pueblo near Clarkdale, Arizona Middle and lower, Montezuma Well and Montezuma Castle cliff dwelling, Camp Verde, Arizona 9 a.m. to 5:30 p.m. Saturday May 8: Southern Sinagua Sites Tour – Montezuma Castle, Montezuma Well, and Tuzigoot meets at Montezuma Castle National Monument, 2800 Montezuma Castle Rd., Camp Verde, Arizona What is Sinagua? Named with the Spanish term sin agua (‘without water’), people of the Sinagua culture inhabited Arizona’s Middle Verde Valley and Flagstaff areas from about 6001400 CE Verde Valley cliff houses below the rim of Montezuma Well and grew corn, beans, and squash in scattered lo- cations. Their architecture included masonry-lined pithouses, surface pueblos, and cliff dwellings. Their pottery included some black-on-white ceramic vessels much like those produced elsewhere by the An- cestral Pueblo people but was mostly plain brown, and made using the paddle-and-anvil technique. Was Sinagua a separate culture from the sur- rounding Ancestral Pueblo, Mogollon, Hohokam, and Patayan ones? Was Sinagua a branch of one of those other cultures? Or was it a complex blending or borrowing of attributes from all of the surrounding cultures? Whatever the case might have been, today’s Hopi Indians consider the Sinagua to be ancestral to the Hopi. -

Arroyo 2015 States and Mexico Through a Treaty, Apportioned 1.5 MAF Elevation 1075 Feet

2015 Closing the Water Demand-Supply Gap in Arizona There is an acknowledged gap between future water of water. As a result, there is no one-size-fits-all solution to demand and supply available in Arizona. In some parts of closing the water demand-supply gap. Arizona, the gap exists today, where water users have been living on groundwater for a while, often depleting what Introduction can be thought of as their water savings account. In other places, active water storage programs are adding to water Many information sources were used to develop this savings accounts. The picture is complicated by variability issue of the Arroyo, which summarizes Arizona’s current in the major factors affecting sources and uses of water water situation, future challenges, and options for closing resources. Water supply depends on the volume that nature the looming water demand-supply gap. Three major provides, the location and condition of these sources, and documents, however, provide its foundation. All three the amount of reservoir storage available. Demand for water conclude that there is likely to be a widening gap between reflects population growth, the type of use, efficiency of supply and demand by mid-century unless mitigating use, and the location of that use. In a relatively short time actions are taken. frame, from 1980 to 2009, Arizona’s population grew from The first document is the Colorado River Basin Water 2.7 million people with a $30-billion economy to nearly 6.6 Supply and Demand Study (http://www.usbr.gov/lc/region/ million people with a $260-billion economy. -

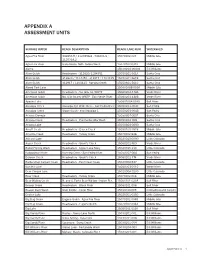

Appendix a Assessment Units

APPENDIX A ASSESSMENT UNITS SURFACE WATER REACH DESCRIPTION REACH/LAKE NUM WATERSHED Agua Fria River 341853.9 / 1120358.6 - 341804.8 / 15070102-023 Middle Gila 1120319.2 Agua Fria River State Route 169 - Yarber Wash 15070102-031B Middle Gila Alamo 15030204-0040A Bill Williams Alum Gulch Headwaters - 312820/1104351 15050301-561A Santa Cruz Alum Gulch 312820 / 1104351 - 312917 / 1104425 15050301-561B Santa Cruz Alum Gulch 312917 / 1104425 - Sonoita Creek 15050301-561C Santa Cruz Alvord Park Lake 15060106B-0050 Middle Gila American Gulch Headwaters - No. Gila Co. WWTP 15060203-448A Verde River American Gulch No. Gila County WWTP - East Verde River 15060203-448B Verde River Apache Lake 15060106A-0070 Salt River Aravaipa Creek Aravaipa Cyn Wilderness - San Pedro River 15050203-004C San Pedro Aravaipa Creek Stowe Gulch - end Aravaipa C 15050203-004B San Pedro Arivaca Cienega 15050304-0001 Santa Cruz Arivaca Creek Headwaters - Puertocito/Alta Wash 15050304-008 Santa Cruz Arivaca Lake 15050304-0080 Santa Cruz Arnett Creek Headwaters - Queen Creek 15050100-1818 Middle Gila Arrastra Creek Headwaters - Turkey Creek 15070102-848 Middle Gila Ashurst Lake 15020015-0090 Little Colorado Aspen Creek Headwaters - Granite Creek 15060202-769 Verde River Babbit Spring Wash Headwaters - Upper Lake Mary 15020015-210 Little Colorado Babocomari River Banning Creek - San Pedro River 15050202-004 San Pedro Bannon Creek Headwaters - Granite Creek 15060202-774 Verde River Barbershop Canyon Creek Headwaters - East Clear Creek 15020008-537 Little Colorado Bartlett Lake 15060203-0110 Verde River Bear Canyon Lake 15020008-0130 Little Colorado Bear Creek Headwaters - Turkey Creek 15070102-046 Middle Gila Bear Wallow Creek N. and S. Forks Bear Wallow - Indian Res. -

Free PDF Download

ARCHAEOLOGY SOUTHWEST CONTINUE ON TO THE NEXT PAGE FOR YOUR magazineFREE PDF (formerly the Center for Desert Archaeology) is a private 501 (c) (3) nonprofit organization that explores and protects the places of our past across the American Southwest and Mexican Northwest. We have developed an integrated, conservation- based approach known as Preservation Archaeology. Although Preservation Archaeology begins with the active protection of archaeological sites, it doesn’t end there. We utilize holistic, low-impact investigation methods in order to pursue big-picture questions about what life was like long ago. As a part of our mission to help foster advocacy and appreciation for the special places of our past, we share our discoveries with the public. This free back issue of Archaeology Southwest Magazine is one of many ways we connect people with the Southwest’s rich past. Enjoy! Not yet a member? Join today! Membership to Archaeology Southwest includes: » A Subscription to our esteemed, quarterly Archaeology Southwest Magazine » Updates from This Month at Archaeology Southwest, our monthly e-newsletter » 25% off purchases of in-print, in-stock publications through our bookstore » Discounted registration fees for Hands-On Archaeology classes and workshops » Free pdf downloads of Archaeology Southwest Magazine, including our current and most recent issues » Access to our on-site research library » Invitations to our annual members’ meeting, as well as other special events and lectures Join us at archaeologysouthwest.org/how-to-help In the meantime, stay informed at our regularly updated Facebook page! 300 N Ash Alley, Tucson AZ, 85701 • (520) 882-6946 • [email protected] • www.archaeologysouthwest.org ARCHAEOLOGY SOUTHWEST SPRING 2014 A QUARTERLY PUBLICATION OF ARCHAEOLOGYmagazine SOUTHWEST VOLUME 28 | NUMBER 2 A Good Place to Live for more than 12,000 Years Archaeology in Arizona's Verde Valley 3 A Good Place to Live for More Than 12,000 Years: Archaeology ISSUE EDITOR: in Arizona’s Verde Valley, Todd W. -

THE WATER QUALITY of the LITTLE COLORADO RIVER WATERSHED Fiscal Year 2007

THE WATER QUALITY OF THE LITTLE COLORADO RIVER WATERSHED Fiscal Year 2007 Prepared by the Surface Water Section March 2009 Publication Number OFR 09-11 LCR REPORT FY 2007 THE WATER QUALITY OF THE LITTLE COLORADO RIVER WATERSHED Fiscal Year 2007 By The Monitoring and Assessments Units Edited by Jason Jones and Meghan Smart Arizona Department of Environmental Quality ADEQ Water Quality Division Surface Water Section Monitoring Unit, Standards & Assessment Unit 1110 West Washington St. Phoenix, Arizona 85007-2935 ii LCR REPORT FY 2007 THANKS: Field Assistance: Anel Avila, Justin Bern, Aiko Condon, Kurt Ehrenburg, Karyn Hanson, Lee Johnson, Jason Jones, Lin Lawson, Sam Rector, Patti Spindler, Meghan Smart, and John Woods. Report Review: Kurt Ehrenburg, Lin Lawson, and Patti Spindler. Report Cover: From left to right: EMAP team including ADEQ, AZGF, and USGS; Rainbow over the Round Valley in the White Mountains; Measuring Tape, and Clear Creek located east of Payson. iii LCR REPORT FY 2007 ABBREVIATIONS Abbreviation Name Abbreviation Name ALKCACO3 Total Alkalinity SO4-T Sulfate Total ALKPHEN Phenolphthalein Alkalinity SPCOND Specific Conductivity Arizona Department of Suspended Sediment AQEQ Environmental Quality SSC Concentration AS-D Arsenic Dissolved su Standard pH Units AS-T Arsenic Total TDS Total Dissolved Solids Arizona Game and Fish AZGF Department TEMP-AIR Air Temperature Arizona Pollutant Discharge TEMP- AZPDES Elimination System WATER Water Temperature BA-D Barium Dissolved TKN Total Kjeldahl Nitrogen B-T Boron Total TMDL Total Maximum Daily Load CA-T Calcium Total USGS U.S. Geological Survey CFS Cubic Feet per Second ZN-D Zinc Dissolved CO3 Carbonate ZN-T Zinc Total CU-TRACE Copper Trace Metal CWA Clean Water Act DO-MGL Dissolved Oxygen in mg/l DO- PERCENT Dissolved Oxygen in Percent E. -

Traditional Resource Use of the Flagstaff Area Monuments

TRADITIONAL RESOURCE USE OF THE FLAGSTAFF AREA MONUMENTS FINAL REPORT Prepared by Rebecca S. Toupal Richard W. Stoffle Bureau of Applied Research in Anthropology University of Arizona Tucson, AZ 86721 July 19, 2004 TRADITIONAL RESOURCE USE OF THE FLAGSTAFF AREA MONUMENTS FINAL REPORT Prepared by Rebecca S. Toupal Richard W. Stoffle Shawn Kelly Jill Dumbauld with contributions by Nathan O’Meara Kathleen Van Vlack Fletcher Chmara-Huff Christopher Basaldu Prepared for The National Park Service Cooperative Agreement Number 1443CA1250-96-006 R.W. Stoffle and R.S. Toupal, Principal Investigators Bureau of Applied Research in Anthropology University of Arizona Tucson, AZ 86721 July 19, 2004 TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF TABLES................................................................................................................... iv LIST OF FIGURES .................................................................................................................iv CHAPTER ONE: STUDY OVERVIEW ..................................................................................1 Project History and Purpose...........................................................................................1 Research Tasks...............................................................................................................1 Research Methods..........................................................................................................2 Organization of the Report.............................................................................................7 -

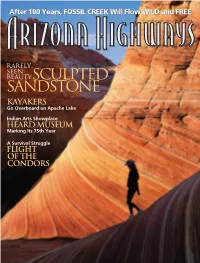

Sculpted Sandstone Kayakers Go Overboard on Apache Lake

After 100 Years, FOSSIL CREEK Will Flow WILD and FREE arizonahighways.com JUNE 2004 rarely seen Beauty Sculpted Sandstone Kayakers Go Overboard on Apache Lake Indian Arts Showplace Heard Museum Marking Its 75th Year A Survival Struggle Flight of the Condors {also inside} JUNE 2004 46 DESTINATION Walnut Canyon The Sinagua Indians had good reason to build their 22 COVER/PORTFOLIO 36 TRAVEL homes along the cliffs of Walnut Canyon. Nature’s Handiwork Chaos in a Tandem Kayak 42 BACK ROAD ADVENTURE in Sandstone Two wigglesome paddlers take a water-camping Drive through the stark beauty of Monument Valley class on Apache Lake and have a boatload of on the Navajo Indian Reservation. The odd shapes of multicolored petrified dunes called trouble getting the hang of capsize recovery. Coyote Buttes grace Arizona’s border with Utah. 48 HIKE OF THE MONTH The route up Strawberry Crater near Flagstaff ENVIRONMENT travels an area once violent Paria Canyon- 6 with volcanic activity. Vermilion Cliffs Fossil Creek Going Wild Again Wilderness By the end of December, this scenic stream in Coyote Monument 2 LETTERS & E-MAIL Buttes Valley central-Arizona will revert to a natural state as two Grand Canyon electric power plants are closed after nearly a 3 TAKING THE National Park OFF-RAMP Strawberry Crater hundred years of operation. Walnut Canyon National Monument 40 HUMOR Fossil MUSEUMS Creek 16 PHOENIX Heard Museum Marks 41 ALONG THE WAY Apache A nostalgic drive across Maricopa Lake Wells 75th Anniversary America is hard to beat— TUCSON Phoenix’s noted institution for Indian arts and culture except by arriving home continues to tie native creativity and traditions to in Arizona. -

Oak Creek Canyon

' " United States (. Il). Department of \~~!J'~~':P Agriculture CoconinoNational Forest Service ForestPlan Southwestern Region -""""" IU!S. IIIII.IIIIII... I I i I--- I I II I /"r, Vicinity Map @ , " .. .' , ",', '. ',,' , ". ,.' , ' ' .. .' ':':: ~'::.»>::~: '::. Published August 1987 Coconino N.ational Forest Land and Resource Management Plan This Page Intentionally Left Blank Coconino Foresst Plan TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION Purpose of the Plan. 1 Organization of the Forest Plan Documentation. 2 Planning Area Description. 2 2. ISSUES Overview . 5 Issues . 5 Firewood . 6 Timber Harvest Levels. 7 The Availability of Recreation Options . 8 Off-Road Driving . 9 Wildlife Habitat . 9 Riparian Habitat . 11 Geothermal Development . .. 11 Management of the Transportation System . 12 Use of the Public Lands . 13 Law Enforcement . 13 Landownership Adjustment . 14 Opportunities . 14 Public Affairs . 14 Volunteers . 15 3. SUMMARY OF THE ANALYSIS OF THE MANAGEMENT SITUATION Overview . 17 Prior Allocations . 18 4. MANAGEMENT DIRECTION Overview . 21 Mission . 21 Goals . 21 Objectives . 26 Regional Guide/Forest Plan . 26 Outputs & Range of Implementation . 26 Management Prescriptions . 46 Management Area Description . 46 Management Emphasis . 46 Program Components . 46 Activities . .. 47 Standards and Guidelines . 47 How to Apply Prescriptions . .. 47 Coordinating Requirements . .. 47 Coconino National Forest Plan – Partial Cancellation of Amendment No. 15 -3/05 Replacement Page i Coconino Forest Plan Table of Contents continued Standards and Guidelines . 51 Forest-wide . 51 MA 1 Wildernesses . 98 MA 2 Verde Wild and Scenic River . .. 113 MA 3 Ponderosa Pine and Mixed Conifer, Less Than 40 Percent Slopes. .. 116 MA 4 Ponderosa Pine and Mixed Conifer, Greater Than 40 Percent Slopes. 138 MA 5 Aspen . 141 MA 6 Unproductive Timber Land . -

EMERGING CONTAMINANTS in ARIZONA WATER a Status Report September 2016

EMERGING CONTAMINANTS IN ARIZONA WATER A Status Report September 2016 CONTAMINANT ASSESSMENT • MONITORING • RESEARCH OPPORTUNITIES • IMPACTS • RESOURCES • COMMUNICATION & OUTREACH Acknowledgements Misael Cabrera APEC Sponsor, ADEQ Director Henry Darwin APEC Sponsor, ADEQ Director (former) Trevor Baggiore APEC Chair, ADEQ Water Quality Division Director Mike Fulton APEC Chair, ADEQ Water Quality Division Director (former) Randy Gottler APEC Co-Chair, City of Phoenix Committee Chairs/Co-chairs* Dan Quintanar Chair, Outreach and Education Committee Tucson Water John Kmiec Chair, Chemical EC Committee Town of Marana Dr. Jeff Prevatt Chair, Microbial EC Committee Pima County Regional Wastewater Reclamation Dept. Cindy Garcia (M) Co-chair, Outreach and Education Committee City of Peoria Jamie McCullough Co-chair, Outreach and Education Committee City of El Mirage Dr. Channah Rock Co-chair, Outreach and Education Committee University of Arizona, Maricopa Agricultural Center Laura McCasland (O) Co-chair, Chemical EC Committee City of Scottsdale Steve Baker Co-chair, Microbial EC Committee Arizona Dept. of Health Services, Division of Public Health Services Additional APEC Members* Dr. Morteza Abbaszadegan (M) Arizona State University, Dept. of Civil and Environmental Engineering Dr. Leif Abrell (C,M) University of Arizona, Arizona Laboratory for Emerging Contaminants Jennifer Botsford (C,O) Arizona Dept. of Health Services, Office of Environmental Health Dr. Kelly Bright (M) University of Arizona, Soil, Water & Environmental Science Al Brown (O) Arizona State University, The Polytechnic School Dr. Mark Brusseau (C,O) University of Arizona, School of Earth & Environmental Sciences Alissa Coes (C) U.S. Geological Survey, Arizona Water Science Center Nick Paretti U.S. Geological Survey, Arizona Water Science Center Patrick Cunningham (O) The Law Office of Patrick J. -

Fall/Winter 2012 Contents New Books 1-17

The University of Utah Press FALL/WINTER 2012 CONTENTS New Books 1-17 New in Paperback 18 Featured Backlist 19-21 Essential Backlist 22-27 Index 28 E-book Availability The University of Utah Press has partnered with the ven- dors and aggregators listed below. Selected frontlist and backlist titles are available as e-books. Please consult the “These letters give a wonderful portrait of their appropriate site for availability and how to purchase. time—from the immediate pre–World War II years Amazon www.amazon.com/kindle-ebooks through the early part of that conflict. They also give the reader an intimate look at a very special literary Barnes & Noble www.barnesandnoble.com/ebooks friendship, one which allowed DeVoto and Sterne Ebsco a unique freedom of expression. This is a significant www.ebscohost.com/ebooks contribution to American intellectual history.” —Carl Brandt, Brandt & Hochman Literary Agents, Inc. Ebrary www.ebrary.com On the Cover: A fine example of architecture in Salt Lake City’s Avenues neighborhood. Photo © Elizabeth Cotter. Our Mission The University of Utah Press is an agency of The University of Utah. In accor- dance with the mission of the University, the Press publishes and disseminates scholarly books in selected fields and other printed and recorded materials of significance to Utah, the region, the country, and the world. The University of Utah Press is a member of the Association of American University Presses. www.UofUpress.com 1 Extraordinary letters between DeVoto and a fan ORD E R S offer a glimpse into the literary, cultural, and : 800-621-2736 historical world of the 1930s and ‘40s WWW.U OF U P R E SS. -

The Rio De Flag (RDF) Wastewater Treatment Plant (WWTP) Is a 4 MGD Plant That Serves the City of Flagstaff Arizona

An Exploration of Nutrient and Community Variables in Effluent Dependent Streams in Arizona David Walker, Ph.D University of Arizona Christine Goforth University of Arizona Samuel Rector Arizona Department of Environmental Quality EPA Grant Number X-828014-01-01 Acknowledgements Without the help of several persons, this work would not have been possible. Shelby Flint. UofA graduate student. Without Shelby’s organizational skills both in the field and lab, this project probably would have come to a screeching halt long ago. Shelby has moved on to bigger and better things but will always be sorely missed. Patti Spindler. Aquatic ecologist from ADEQ provided invaluable field and technical expertise. Emily Hirleman.. UofA graduate student. Field, laboratory, and comedic assistance. Nick Paretti. UofA graduate student. Field and laboratory assistance. Leah Bymers. UofA graduate student. Field and laboratory assistance. Elzbieta and Wit Wisniewski. UofA graduate students. Field assistance. Linda Taunt. Head of the Hydrological Support and Assessment Unit, ADEQ. Moral support (did I say I’d have it done on Wednesday?....I meant Thursday…or Friday…maybe next week) Susan Fitch. ADEQ. An endless supply of moral support. Steven Pawlowski. ADEQ. Technical expertise, reviewer, grant manager, and good guy. 2 Introduction 3 Relatively little information is known about waters within Arizona designated “aquatic and wildlife, effluent dependent” (EDW) and even less is known about biological communities living in waters designated as such. Nutrient levels are not routinely required in NPDES permits from these waters so that historical data is either lacking or non-existent. One aspect of EDW’s that is certain is that they will increase in number and importance as population centers increase. -

The East Verde Is a Rapidly Degrading Stream Flowing Through a Country Of

An archeological reconnaissance of the East Verde River in central Arizona Item Type Thesis-Reproduction (electronic); text Authors Peck, Fred Rawlings,1925- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 23/09/2021 22:17:51 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/191414 FroritespieCe The East Verde is a rapidly degradingstream flowing through a country of high relief. AN AtC HEOLOGICAL RECO ISANCE OF THE Ei$T VERDE RIVER IN CENTPLMIDNA by Fred R. Peck A Thesis submitted to the faculty of the Department of Anthropology in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of M$TER OF ARTS in the Graduate College, University of Arizona l96 Approved: Director of T is Y Date /95 This thesis has been submitted in partial fulfillment of requirements for an advanced degree at the University of Arizona and is deposited in the Library to be made available to borrowers under rules of the Library. Brief quotations from this thesis are allowable without special permission, provided that accurate acknowledgment of source is made. Requests for permission for extended quotation from or repro- duction of this manuscript in whole or in part may be granted by the head of the major department or the dean of the Graduate College when in their judgment the proposed use of the material is in the interests of scholarship.