Zionism I INTRODUCTION II HISTORICAL BACKGROUND A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Resolutions of the Zionist Congress Xxxvii

1 2 RESOLUTIONS OF THE ZIONIST CONGRESS XXXVII TABLE OF CONTENTS NO. TITLE PAGE 1 The Declaration of Independence as a Zionist Tool 4 2 Non-Stop Zionism 4 3 WZO Involvement in Israeli Society 5 4 The Unity of the Jewish People 5-6 5 The Restitution of Jewish Refugees' Property 6 6 Recognition of the Jewish People as Indigenous to the Land of Israel 6-7 7 Preserving a Healthy Climate for Israel’s Future 7 8 Protecting Israel’s Water Supply from Pollution 7-8 9 Appropriate Zionist Response 8 10 The Intensification of Zionist Advocacy (Hasbara) 8 11 National and International Issues 8-9 12 The State of Israel’s Relations with USA Jewry 9 Deepening the Connection between Israeli Society and Communities of Israeli Yordim 13 9 in the Diaspora 14 Israeli Government Initiative with the International Jewish Community 9-10 15 Zionist Movement Activity in Light of Escalating Antisemitism 10 16 Aliyah Promotion and Countering Antisemitism 10 17 Withholding Funds from Entities Hostile to Israel 11 18 Development of Young Zionist Leadership 11 19 Establishment of an Institute for Zionist Education 11-12 20 Prevention of Assimilation 12 21 Young Leadership 12 22 Ingathering of the Exiles (1) 12-13 23 Ingathering of the Exiles (2) 13 24 Ingathering of the Exiles (3) 13 25 Enhancement of Activity to Promote Aliyah 13-14 26 Hebrew Language #2 14 27 Aliyah 14-15 3 NO. TITLE PAGE 28 Absorption of Ethiopian Jews 15 29 Establishment of an Egalitarian Prayer Space at the Western Wall 15-16 30 The Druze Zionist Movement 16 31 Opposition to Hate Crimes 16 32 Refining -

Forming a Nucleus for the Jewish State

Table of Contents Introduction ........................................................................................... 3 Jewish Settlements 70 CE - 1882 ......................................................... 4 Forming a Nucleus for First Aliyah (1882-1903) ...................................................................... 5 Second Aliyah (1904-1914) .................................................................. 7 the Jewish State: Third Aliyah (1919-1923) ..................................................................... 9 First and Second Aliyot (1882-1914) ................................................ 11 First, Second, and Third Aliyot (1882-1923) ................................... 12 1882-1947 Fourth Aliyah (1924-1929) ................................................................ 13 Fifth Aliyah Phase I (1929-1936) ...................................................... 15 First to Fourth Aliyot (1882-1929) .................................................... 17 Dr. Kenneth W. Stein First to Fifth Aliyot Phase I (1882-1936) .......................................... 18 The Peel Partition Plan (1937) ........................................................... 19 Tower and Stockade Settlements (1936-1939) ................................. 21 The Second World War (1940-1945) ................................................ 23 Postwar (1946-1947) ........................................................................... 25 11 Settlements of October 5-6 (1947) ............................................... 27 First -

Arab-Israeli Relations

FACTSHEET Arab-Israeli Relations Sykes-Picot Partition Plan Settlements November 1917 June 1967 1993 - 2000 May 1916 November 1947 1967 - onwards Balfour 1967 War Oslo Accords which to supervise the Suez Canal; at the turn of The Balfour Declaration the 20th century, 80% of the Canal’s shipping be- Prepared by Anna Siodlak, Research Associate longed to the Empire. Britain also believed that they would gain a strategic foothold by establishing a The Balfour Declaration (2 November 1917) was strong Jewish community in Palestine. As occupier, a statement of support by the British Government, British forces could monitor security in Egypt and approved by the War Cabinet, for the establish- protect its colonial and economic interests. ment of a national home for the Jewish people in Palestine. At the time, the region was part of Otto- Economics: Britain anticipated that by encouraging man Syria administered from Damascus. While the communities of European Jews (who were familiar Declaration stated that the civil and religious rights with capitalism and civil organisation) to immigrate of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine to Palestine, entrepreneurialism and development must not be deprived, it triggered a series of events would flourish, creating economic rewards for Brit- 2 that would result in the establishment of the State of ain. Israel forcing thousands of Palestinians to flee their Politics: Britain believed that the establishment of homes. a national home for the Jewish people would foster Who initiated the declaration? sentiments of prestige, respect and gratitude, in- crease its soft power, and reconfirm its place in the The Balfour Declaration was a letter from British post war international order.3 It was also hoped that Foreign Secretary Lord Arthur James Balfour on Russian-Jewish communities would become agents behalf of the British government to Lord Walter of British propaganda and persuade the tsarist gov- Rothschild, a prominent member of the Jewish ernment to support the Allies against Germany. -

Steps to Statehood Timeline

STEPS TO STATEHOOD TIMELINE Tags: History, Leadership, Balfour, Resources 1896: Theodor Herzl's publication of Der Judenstaat ("The Jewish State") is widely considered the foundational event of modern Zionism. 1917: The British government adopted the Zionist goal with the Balfour Declaration which views with favor the creation of "a national home for the Jewish people." / Balfour Declaration Feb. 1920: Winston Churchill: "there should be created in our own lifetime by the banks of the Jordan a Jewish State." Apr. 1920: The governments of Britain, France, Italy, and Japan endorsed the British mandate for Palestine and also the Balfour Declaration at the San Remo conference: The Mandatory will be responsible for putting into effect the declaration originally made on November 8, 1917, by the British Government, and adopted by the other Allied Powers, in favour of the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people. July 1922: The League of Nations further confirmed the British Mandate and the Balfour Declaration. 1937: Lloyd George, British prime minister when the Balfour Declaration was issued, clarified that its purpose was the establishment of a Jewish state: it was contemplated that, when the time arrived for according representative institutions to Palestine, / if the Jews had meanwhile responded to the opportunities afforded them ... by the idea of a national home, and had become a definite majority of the inhabitants, then Palestine would thus become a Jewish commonwealth. July 1937: The Peel Commission: 1. "if the experiment of establishing a Jewish National Home succeeded and a sufficient number of Jews went to Palestine, the National Home might develop in course of time into a Jewish State." 2. -

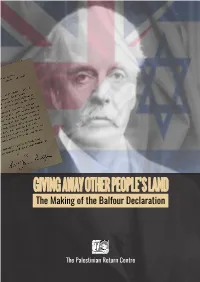

The Making of the Balfour Declaration

The Making of the Balfour Declaration The Palestinian Return Centre i The Palestinian Return Centre is an independent consultancy focusing on the historical, political and legal aspects of the Palestinian Refugees. The organization offers expert advice to various actors and agencies on the question of Palestinian Refugees within the context of the Nakba - the catastrophe following the forced displacement of Palestinians in 1948 - and serves as an information repository on other related aspects of the Palestine question and the Arab-Israeli conflict. It specializes in the research, analysis, and monitor of issues pertaining to the dispersed Palestinians and their internationally recognized legal right to return. Giving Away Other People’s Land: The Making of the Balfour Declaration Editors: Sameh Habeeb and Pietro Stefanini Research: Hannah Bowler Design and Layout: Omar Kachouch All rights reserved ISBN 978 1 901924 07 7 Copyright © Palestinian Return Centre 2017 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publishers or author, except in the case of a reviewer, who may quote brief passages embodied in critical articles or in a review. مركز العودة الفلسطيني PALESTINIAN RETURN CENTRE 100H Crown House North Circular Road, London NW10 7PN United Kingdom t: 0044 (0) 2084530919 f: 0044 (0) 2084530994 e: [email protected],uk www.prc.org.uk ii Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................3 -

“To Be an American”: How Irving Berlin Assimilated Jewishness and Blackness in His Early Songs

“To Be an American”: How Irving Berlin Assimilated Jewishness and Blackness in his Early Songs A document submitted to The Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS in the Performance Studies Division of the College-Conservatory of Music 2011 by Kimberly Gelbwasser B.M., Northwestern University, 2004 M.M., University of Cincinnati, 2006 Committee Chair: Steven Cahn, Ph.D. Abstract During the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, millions of immigrants from Central and Eastern Europe as well as the Mediterranean countries arrived in the United States. New York City, in particular, became a hub where various nationalities coexisted and intermingled. Adding to the immigrant population were massive waves of former slaves migrating from the South. In this radically multicultural environment, Irving Berlin, a Jewish- Russian immigrant, became a songwriter. The cultural interaction that had the most profound effect upon Berlin’s early songwriting from 1907 to 1914 was that between his own Jewish population and the African-American population in New York City. In his early songs, Berlin highlights both Jewish and African- American stereotypical identities. Examining stereotypical ethnic markers in Berlin’s early songs reveals how he first revised and then traded his old Jewish identity for a new American identity as the “King of Ragtime.” This document presents two case studies that explore how Berlin not only incorporated stereotypical musical and textual markers of “blackness” within two of his individual Jewish novelty songs, but also converted them later to genres termed “coon” and “ragtime,” which were associated with African Americans. -

Now and Forever — a Conversation with Israel Zangwill (New York: Robert M

Now and Forever — A Conversation with Israel Zangwill (New York: Robert M. McBride & Co., 1925), 156 pp. Another "by Jews, for Jews" special, from the Memory Hole. The tone of works such as this is quite different from what is presented in the media for general (i.e., "gentile") consumption. A strange little book I picked up. Samuel Roth discusses the state of Jewry with Israel Zangwill. Zangwill was a playwright who coined the phrase "melting pot" and who wrote a standard "refutation" of the Protocols . It deals with how Jews see themselves -- and how they think others see them. It's funny to see two Jews pretending to be "against" one another in a debate -- like two ants from the same anthill. All the extreme arrogance and subjectivity of Jews is displayed here. Jews are distinctive in the world in raising such things to near hallucinogenic levels. Compare with Hosmer and Marcus Eli Ravage. Some of the most incredible (or oddly candid) statements I highlighted in red as I went thru' the text. Jews say "we're special because we remember" -- their way of saying they institutionalize trans-generational ethnic hatred as a way of separating themselves from the rest of human society. My favorite part -- Roth compares St. Paul with Trotsky! He further says that Jews are the only real Christians, and that "Jesus preached of Jews and for Jews". He says that Jesus hated the world (when he really just hated Jews -- but Jews are "the world", according to them: all others are "not of Adam"). But we mustn't forget that this Problem is primarily an ethnic, and not a religious, one. -

Lazarus, Syrkin, Reznikoff, and Roth

Diaspora and Zionism in Jewish American Literature Brandeis Series in American Jewish History,Culture, and Life Jonathan D. Sarna, Editor Sylvia Barack Fishman, Associate Editor Leon A. Jick, The Americanization of the Synagogue, – Sylvia Barack Fishman, editor, Follow My Footprints: Changing Images of Women in American Jewish Fiction Gerald Tulchinsky, Taking Root: The Origins of the Canadian Jewish Community Shalom Goldman, editor, Hebrew and the Bible in America: The First Two Centuries Marshall Sklare, Observing America’s Jews Reena Sigman Friedman, These Are Our Children: Jewish Orphanages in the United States, – Alan Silverstein, Alternatives to Assimilation: The Response of Reform Judaism to American Culture, – Jack Wertheimer, editor, The American Synagogue: A Sanctuary Transformed Sylvia Barack Fishman, A Breath of Life: Feminism in the American Jewish Community Diane Matza, editor, Sephardic-American Voices: Two Hundred Years of a Literary Legacy Joyce Antler, editor, Talking Back: Images of Jewish Women in American Popular Culture Jack Wertheimer, A People Divided: Judaism in Contemporary America Beth S. Wenger and Jeffrey Shandler, editors, Encounters with the “Holy Land”: Place, Past and Future in American Jewish Culture David Kaufman, Shul with a Pool: The “Synagogue-Center” in American Jewish History Roberta Rosenberg Farber and Chaim I. Waxman,editors, Jews in America: A Contemporary Reader Murray Friedman and Albert D. Chernin, editors, A Second Exodus: The American Movement to Free Soviet Jews Stephen J. Whitfield, In Search of American Jewish Culture Naomi W.Cohen, Jacob H. Schiff: A Study in American Jewish Leadership Barbara Kessel, Suddenly Jewish: Jews Raised as Gentiles Jonathan N. Barron and Eric Murphy Selinger, editors, Jewish American Poetry: Poems, Commentary, and Reflections Steven T.Rosenthal, Irreconcilable Differences: The Waning of the American Jewish Love Affair with Israel Pamela S. -

THE STATE of ISRAEL 70 YEARS of INDEPENDENCE - Building a Nation

1 The Zionist General Council Session XXXVII/4 THE STATE OF ISRAEL 70 YEARS OF INDEPENDENCE - Building a Nation October 2018 2 Plenary No. 1 - Opening of the Zionist General Council Session Eli Cohen opened the first session and thanked the members of the audit committee and praised the auditor and his team, who - in their attempt to reach a level of satisfaction, which all can find to be acceptable - see all the flaws and improvements. Rabbi Yehiel Wasserman was invited to the stage for a ceremony conferring honorary fellowships to various members for their activities in the Zionist movement and their significant contribution to shaping its path and activities. This year, thanks to the WZO’s extensive activity over the past decade, quite a few people will be receiving this status. Honorary fellows are highly motivated individuals who have devoted many years of their time to the Zionist movement and who are role models for the next generation. Rabbi Wasserman then thanked the members of the Committee for Honorary Fellows: Barbara Goldstein, Silvio Joskowicz, Dalia Levy, Karma Cohen, Hernan Felman, Jacques Kupfer and Nava Avissar, the committee’s coordinator, for their dedicated work. Honorary Fellows: Mrs. Ana Marlene Starec – Mrs. Starec has been active in the Zionist movement for the past 54 years. She has been serving as Honorary President of WIZO for many years now and is also engaged in advocacy activities for Israel in the Diaspora in general, and with the Jewish communities of Brazil, in particular. Her human rights activities earned her a medal from the state of Rio de Janeiro, and she has also received a medal from the French Senate for her activities for humanity. -

CAUTION: ZIONISM! Essays on the Ideology, Organisation and Practice of Zionism

CAUTION: ZIONISM! Essays on the Ideology, Organisation and Practice of Zionism Yuri Ivanov Moscow Progress Publishers 1970 Contents Preface I Myth and Reality II "A Time to Cast Stones and a Time to Gather Stones Together" III Roofless Labyrinth IV Crossroads V Caution: Zionism! To fellow countrymen and foreign comrades whose kind advice has been of such help. Yuri Ivanov Preface Gone are the days when the enemies of the young Soviet republic fervently awaited the collapse of the world's first workers' and peasants' state. The Land of Soviets proved its viability in the face of armed intervention and its magnificent performance in the life- and-death struggle against the nazi hordes already belongs to history. Gone, indeed, are many of the illusions harboured by the enemies of communism, but not their hatred and their intention to continue the struggle with all the means that remain at their disposal. Lenin held that it was the fundamental duty of the Soviet press to make a concrete analysis of the forces acting against communism, however secondary they might appear at first glance. This book makes a study of modern Zionism, one of the most tenacious, though veiled varieties of anti-communism. Meir Vilner, Secretary of the Political Bureau of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Israel, wrote in a letter to Soviet journalists in January 1968: "Zionism is, alas, a 'forgotten' question but nonetheless a most actual one. ." How right he is! For a long time many champions of Zionism were sparing no efforts to make Zionism appear nothing more than an obsolete term. -

Jewish State and Jewish Land Program Written in Jerusalem by Yonatan Glaser, UAHC Shaliach, 2003

December 2003 \ Kislev 5764 Jewish State and Jewish Land Program written in Jerusalem by Yonatan Glaser, UAHC Shaliach, 2003 Rationale We live in a time where taking an interest in Israel is not taken for granted and where supporting Israel, certainly in parts of our public life like on campus, may be done at a price. Even in the best of times, it is important to be conceptually clear why we Jews want our own country. What can and should it mean to us, how might it enrich and sustain us – those of us who live in it and those of us who do not? What might contributing to its well-being entail? If that is at the best of times, then this – one of the most difficult times in recent memory – is an excellent time to re- visit the basic ideas and issues connected to the existence of Israel as a Jewish state in the ancient Land of Israel. With this in mind, this program takes us on a ‘back to basics’ tour of Israel as a Jewish country in the Jewish Land. Objectives 1. To explore the idea of Jewish political independence. 2. To explore the meaning of Jewish historical connection to Eretz Yisrael 3. To learn about the Uganda Plan in order to recognize that issues connected to independence and living in Eretz Yisrael have been alive and relevant for at least the last 100 years. Time 1 hour and fifteen minutes Materials 1. Copies of the four options (Attachment #1) 2. White Board or poster Board. -

Bibliography

Bibliography Abrams, Ruth. ‘Jewish Women in the International Woman Suffrage Alliance, 1899–1926’. PhD diss., Brandeis University, 1997. Abse, Leo. ‘A Tale of Collaboration not Conflict with the “People of the Book” ’. Review of The Jews of South Wales, ed. Ursula Henriques. New Welsh Review, 6.2 (1993): 16–21. Ackroyd, Peter. London: The Biography. London: Chatto & Windus, 2001. Alderman, Geoffrey. ‘The Anti-Jewish Riots of August 1911 in South Wales’. Welsh History Review, 6.2 (1972): 190–200. ———. ‘The Jew as Scapegoat? The Settlement and Reception of Jews in South Wales before 1914’. Jewish Historical Society of England: Transactions, 26 (1974–78): 62–70. ———. Modern British Jewry. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1992. Alleyne, Brian. ‘An Idea of Community and Its Discontents: Towards a More Reflexive Sense of Belonging in Multicultural Britain’. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 25.4 (2002): 607–627. Arata, Stephen D. ‘The Occidental Tourist: Dracula and the Anxiety of Reverse Colonization’. Victorian Studies, 33.4 (1990): 62–45. Avineri, Shlomo. ‘Theodor Herzl’s Diaries as a Bildungsroman’. Jewish Social Studies, 5.3 (1999): 1–46. Avitzur, Shmuel. The Industry of Action: A Collection on the History of Israeli Industry, in Commemoration of Nahum Wilbusch, Pioneer of the New Hebrew Industry in Israel. Tel-Aviv: Milo, 1974. [Hebrew]. Back, Les. New Ethnicities and Urban Culture: Racisms and Multiculture in Young Lives. London: Routledge, 1996. Bakhtin, Mikhail. Rabelais and His World. Trans. Helene Iswolsky. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1968. Bar-Avi, Israel. Dr Moses Gaster. Jerusalem: Cénacle Littéraire ‘Menorah’, 1973. Bareli, Avi. ‘Forgetting Europe: Perspectives on the Debate about Zionism and Colonialism’.