Facets of Public Health in Europe

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Determinants of Healthy Ageing in European Countries

Open Access Journal of Gerontology & Geriatric Medicine ISSN: 2575-8543 Research Article OAJ Gerontol & Geriatric Med Volume 4 Issue 5 - February 2019 Copyright © All rights are reserved by Wim JA van den Heuvel DOI: 10.19080/OAJGGM.2019.04.555649 Determinants of Healthy Ageing in European countries Wim JA van den Heuvel1* and Marinela Olaroiu2 1Share Research Institute, University Medical Centre, Netherlands 2Foundation Research and Advice in Care for Elderly (RACE), Heggerweg 2a, Netherlands Submission: January 24, 2019; Published: February 26, 2019 *Corresponding author: Wim JA van den Heuvel, Share Research Institute, University Medical Centre, Netherlands Abstract Background and Objectives: The concept of healthy ageing is still at debate, although healthy ageing is recognized as an important policy objective internationally. Evidence of which determinants or policies at country level may affect healthy ageing is lacking. This study explores level indicates the proportion of citizens at risk for poverty and access to services. Social cohesion at national level describes the extent to whichthe relationship citizens are between willing vulnerability,to accept each social other. cohesion, Resilience and at nationalresilience, level and includes healthy nationalageing in resources 31 European for citizens, countries. which Vulnerability may support at nationalthem to overcome adverse events. Research Design and Methods: This comparative study includes data from 2013 or 2014, based on validated, comparable international data sets, i.e. Eurostat and European Social Survey. Healthy ageing describes how many years a person is expected to live in good perceived health. Healthy ageing combines life expectancy with self-perceived health. Vulnerability, social cohesion and resilience are assessed using 10 indicators,Results: selected Mean healthy from the ageing mentioned in the 31data European sets. -

Vorsorge Verzehr Verkehr

06/2011 · 4. Jahrgang Magazin der Wirtschaftsförderung der Stadt Willich für Unternehmer Vorsorge Verzehr Verkehr Gesund bleiben Mittagstisch für Shuttlebus für am Arbeitsplatz Mitarbeiter Gewerbegebiet WIR ist für Sie! – WIR ist DIE Plattform für Willicher Unternehmer Informationen, Termine, Treffen, Portraits, Netzwerk – Die Wirtschaftsförderung der Stadt Willich bietet in ihrem Magazin WIR einen Rundum-Service für alle Unternehmer in der Stadt Willich WIR... ... ist ein Projekt der Wirtschaftsförderung der Stadt Willich Entstanden auf Anregungen Willicher Unternehmer, die Vernetzung der zahlreichen Unternehmen in Willich zu verbessern, ist das Magazin ein Forum für Nachrichten, Informationen und Entwicklungen für und aus Willicher Unternehmen. ... informiert über Themen und Events aus dem Rathaus und aus der Wirtschaft Die Herausgeberin, die Wirtschaftsförderung der Stadt Willich, sorgt mit vielfältigen Aktivitäten und Veranstaltungen für eine umfassende Infor- mation und Betreuung der Unternehmen. Ihre Ansprechpartner sind: ... informiert über Themen, die Unternehmer in Willich interessieren Jede Ausgabe hat Schwerpunkthemen, die für die Willicher Wirtschaft • Josef Heyes • Martina Stall interessant sind - für Anregungen sind wir jederzeit offen! Bürgermeister Technische 949-164 Beigeordnete [email protected] 949-276 [email protected] ... will Netzwerke knüpfen und Synergie-Effekte schaffen Die Veröffentlichung von Nachrichten aus den Unternehmen der lokalen Wirtschaft ist wesentlicher Teil des redaktionellen Inhalts und natürlich • Andrea Ritter • Christian Hehnen kostenfrei - z.B.: Neue Betriebe, An- und Umsiedlungen, Kooperationen Leiterin der Gewerbegebiete Wirtschaftsförderung und Neuansiedlung / Namen und Nachrichten: Personalien, Jubiläen, Ehrungen / Willicher 949-296 949-281 [email protected] [email protected] Unternehmen engagieren sich (sozial, kulturell) / Buchempfehlungen / Lese-Tipps: Wirtschaft, Finanzen, Recht, Personal, Umwelt. -

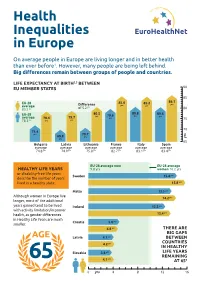

Health Inequalities in Europe (JAHEE)

90 85 86.1 yrs 85.2 85.6 EU-28 yrs yrs Difference yrs average of 5.2 83.5 yrs 80 80.6 80.8 80.5 EU-28 yrs yrs 79.6 yrs yrs 78.4 79.7 average 75 Health yrs yrs 78.3 yrs 70 71.4 yrs 70.7 69.8 yrs Inequalities yrs yrs 65 Spain Italy France Bulgaria Latvia Lithuania average average average average average average in Europe yrs yrs yrs yrs yrs yrs 83.4 83.1 82.7 74.8 74.9 75.8 On average people in Europe are living longer and in better health than ever before1. However, many people are being left behind. Big differences remain between groups of people and countries. LIFE EXPECTANCY AT BIRTH2,3 BETWEEN EU MEMBER STATES 90 85 86.1 EU-28 85.6 85.2 yrs Difference yrs yrs average yrs 83.5 yrs of 5.2 80 EU-28 80.5 80.8 80.6 yrs 79.6 yrs yrs average 78.4 79.7 yrs 75 78.3 yrs yrs yrs 70 71.4 yrs 70.7 69.8 yrs yrs yrs 65 Bulgaria Latvia Lithuania France Italy Spain average average average average average average 74.8 yrs 74.9 yrs 75.8 yrs 82.7 yrs 83.1 yrs 83.4 yrs EU-28 average men EU-28 average HEALTHY LIFE YEARS 9.8 yrs women 10.2 yrs or disability-free life years Sweden 15.4 yrs describe the number of years lived in a healthy state. -

Programme Book Is Printed on FSC Mix Paper

9th European Public Health Conference OVERVIEW PROGRAMME All for Health, WEDNESDAY 9 NOVEMBER THURSDAY 10 NOVEMBER FRIDAY 11 NOVEMBER SATURDAY 12 NOVEMBER 09:00 – 17:00 08:30 – 12:00 8:30 – 9:30 8:30 – 9:30 Pre-conferences Pre-conferences Parallel session 4 Parallel session 8 Health for All 9:40-10:40 9:40 – 10:40 Plenary 2 Parallel session 9 10:30 10:00 10:40 10:40 Coffee/tea break Coffee/tea break Coffee/tea break Coffee/tea break 10th European Public Health Conference 2017 11th European Public Health Conference 2018 11:10-12:40 11:10 – 12:40 Stockholm, Sweden Ljubljana, Slovenia Parallel session 5 Parallel session 10 PROGRAMME 12:30 12:00 12:40 - 14:00 12:40 Lunch for pre-conference Lunch for pre-conference Lunch break Lunch break delegates only delegates only Lunch symposiums Join the Networks 13:00 – 13:40 14:00 – 15:00 13:40 – 14:40 Opening ceremony Plenary 3 Plenary 5 13:50 – 14:50 15:10 – 16:10 14:40 – 15:25 Parallel session 1 Parallel session 6 Closing ceremony Sustaining resilient Winds of Change: towards new ways 15:00 – 16:00 and healthy communities of improving public health in Europe Plenary 1 15:00 16:00 16:10 1 November - 4 November 2017 28 November - 1 December 2018 Coffee/tea break Coffee/tea break Coffee/tea break Stockholmsmässan, Stockholm Cankarjev Dom, Ljubljana 16:30 – 17:30 16:40 – 17:40 Parallel session 2 Parallel session 7 #ephstockholm #eph2018 17:40 – 18:40 17:50 – 18:50 Parallel session 3 Plenary 4 19:30 – 22:00 19:30 – 23:59 Welcome reception Conference dinner 9 - 12 November 2016 www.ephconference.eu @ephconference -

Improving Healthcare Quality in Europe

Cover_WHO_nr52.qxp_Mise en page 1 20/08/2019 16:31 Page 1 51 THE ROLE OF PUBLIC HEALTH ORGANIZATIONS IN ADDRESSING PUBLIC HEALTH PROBLEMS IN EUROPE PUBLIC HEALTH IN ADDRESSING ORGANIZATIONS PUBLIC HEALTH THE ROLE OF Quality improvement initiatives take many forms, from the creation of standards for health Improving healthcare 53 professionals, health technologies and health facilities, to audit and feedback, and from fostering a patient safety culture to public reporting and paying for quality. For policy- makers who struggle to decide which initiatives to prioritise for investment, understanding quality in Europe Series the potential of different quality strategies in their unique settings is key. This volume, developed by the Observatory together with OECD, provides an overall conceptual Health Policy Health Policy framework for understanding and applying strategies aimed at improving quality of care. Characteristics, effectiveness and Crucially, it summarizes available evidence on different quality strategies and provides implementation of different strategies recommendations for their implementation. This book is intended to help policy-makers to understand concepts of quality and to support them to evaluate single strategies and combinations of strategies. Edited by Quality of care is a political priority and an important contributor to population health. This Reinhard Busse book acknowledges that "quality of care" is a broadly defined concept, and that it is often Niek Klazinga unclear how quality improvement strategies fit within a health system, and what their particular contribution can be. This volume elucidates the concepts behind multiple elements Dimitra Panteli of quality in healthcare policy (including definitions of quality, its dimensions, related activities, Wilm Quentin and targets), quality measurement and governance and situates it all in the wider context of health systems research. -

Rethinking European Union Foreign Policy Prelims 7/6/04 9:46 Am Page Ii

prelims 7/6/04 9:46 am Page i rethinking european union foreign policy prelims 7/6/04 9:46 am Page ii EUROPE IN CHANGE T C and E K already published The formation of Croatian national identity A centuries old dream . Committee governance in the European Union ₍₎ Theory and reform in the European Union, 2nd edition . , . , German policy-making and eastern enlargement of the EU during the Kohl era Managing the agenda . The European Union and the Cyprus conflict Modern conflict, postmodern union The time of European governance An introduction to post-Communist Bulgaria Political, economic and social transformation The new Germany and migration in Europe Turkey: facing a new millennium Coping with intertwined conflicts The road to the European Union, volume 2 Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania () The road to the European Union, volume 1 The Czech and Slovak Republics () Europe and civil society Movement coalitions and European governance Two tiers or two speeds? The European security order and the enlargement of the European Union and NATO () Recasting the European order Security architectures and economic cooperation The emerging Euro-Mediterranean system . . prelims 7/6/04 9:46 am Page iii Ben Tonra and Thomas Christiansen editors rethinking european union foreign policy Modern conflict, postmodern union Security architectures and economic cooperation MANCHESTER UNIVERSITY PRESS Manchester and New York distributed exclusively in the USA by Palgrave prelims 7/6/04 9:46 am Page iv Copyright © Manchester University Press 2004 While copyright in the volume as a whole is vested in Manchester University Press, copyright in individual chapters belongs to their respective authors. -

Barometer on Pilot Fatigue Brings Together Several Surveys on Pilot Fatigue Carried out by Member Associations of the European Cockpit Association

Pilot fatigue Barometer 1 Introduction Pilot fatigue Over the last few years, fatigue among pilots and cabin crew has become a genuine concern in the aviation world. Despite scientific studies showing that fatigue could jeopardise the safety of air operations, data about the prevalence of fatigue across Europe is scarce. With estimates of an approximate doubling of air traffic by 2020, quantifying this phenomenon becomes of major importance for the aviation world. Following the example of the Norwegian public service broadcaster, NRK, which revealed very high levels of fatigue, ECA Member Associations have taken up the challenge of surveying thousands of pilots across Europe. The intention of this Barometer is to take stock of the prevalence of fatigue in Europe’s cockpits by looking into fatigue polls, conducted by ECA members. This publication comes at a time when the European Aviation Safety Agency (EASA) has published a final proposal for Flight and Duty Time Regulations and the European Commission is to approve or amend it. We hope that the data compiled will serve as useful input for the related decision-making process. 2 © Andreas Tittelbach pilot fatigue Executive summary The 2012 Barometer on Pilot Fatigue brings together several surveys on pilot fatigue carried out by Member Associations of the European Cockpit Association. Between 2010 and 2012, more than 6.000 European pilots have been asked to self-assess the level of fatigue they are experiencing. The surveys confirm that pilot fatigue is common, dangerous and an under-reported phenomenon in Europe. • Over 50% of surveyed pilots experience fatigue as impairing their ability to perform well while on flight duty. -

Norwegian Actors' Engagement in Global Health to Contents the New Goals Must Be Simple and Measurable, Necessitating the Need for Clarity and Good Data

Meld.St. 11 (2011-2012) (white paper) Global health in foreign and development policy (2011-2012) Meld.St. 11 Meld.St. 11 (2011-2012) (white paper) Global health in foreign and development policy Norwegian actors' engagement in global health Commitments to global health by Norwegian actors Content Foreword Norwegian Knowledge Centre for the Espen Barth Eide, Minister of Foreign Affairs Health Services Heikki Eidsvoll Holmås, Minister of Magne Nylenna, Chief Executive 26 International Development Jonas Gahr Støre, Minister of Health Haukeland University Hospital (HUS) and Care Services 4 Jon Wigum Dahl, Director 28 Ministry of Foreign Affairs Oslo University Hospital Gry Larsen and Arvinn Eikeland Gadgil Kristin Schjølberg Hanche-Olsen State Secretaries 6 Head of Section 30 Ministry of Health and Care Services Statistics Norway (HOD) Bjørn Kjetil Getz Wold, Head of Division 32 Nina Tangnæs Grønvold, State Secretary 8 Sørlandet Hospital Ministry of Children, Equality Anders Wahlstedt, International Coordinator 34 and Social Inclusion Ahmad Ghanizadeh, State Secretary 10 Norwegian Health Network for Development Ministry of Agriculture and Food 12 Anders Wahlstedt, Chair of the Board 35 Norwegian Directorate of Health Chr. Michelsen Institute (CMI) Bjørn Guldvog, Director 14 Ottar Mæstad, Director 36 Norad Fafo Villa Kulild, Director General 16 Jon Pedersen, Managing Director 38 The Research Council of Norway Norwegian Forum for Global Health Mari Kristine Nes, Director General 18 Research (The Forum) Inger B. Sheel, Chair of the Board 40 FK Norway (Fredskorpset) Nita Kapoor, Director General 20 Peace Research Institute Oslo (PRIO) Henrik Urdal, Senior Researcher 42 Norwegian Institute of Public Health (NIPH) Faculty of Medicine, NTNU Camilla Stoltenberg, Director General 22 Stig A. -

Nippon Nachbarn Nachhaltig

Dez. 2018 - Feb. 2019 · 11. Jahrgang Magazin der Wirtschaftsförderung der Stadt Willich für Unternehmer NIPPON NACHBARN NACHHALTIG Bürgermeister besucht Netzwerk für Willicher rüsten Firmen in Japan BGM-Maßnahmen für die Zukunft WIR · Magazin für Unternehmen in der Stadt Willich / Dezember 2018 - Februar 2019 WIR · Magazin für Unternehmen in der Stadt Willich / Dezember 2018 - Februar 2019 Schneller, stabiler, EDITORIAL Sehr verehrte Willicher Unternehmerinnen, sehr geehrte Willicher Unternehmer, wirtschaftlicher. …kann es jetzt schon hören: „Modern ist, was Erfolg hat.“ Mag ja auf kurze Sicht sein – und trotzdem lohnt es sich, beim Thema „Moderne Unternehmensführung“, mit dem sich diese Ausgabe des WIR-MAGAZINs beschäftigt, einmal genauer hinzuschauen. Halten Sie sich für einen modernen Unternehmer? Was macht den eigentlich genau aus? Führung ganz sicher – und damit auch „moderne Führung“. Glasfaser für Ihr Die findet ja auf verschiedene Ebenen statt: Ganz sicher auch auf der der strukturellen Hierarchien, aber natürlich auch auf der Ebene der Qualität der Beziehungen zwischen Mitarbeitern und Führungskräften. Was also bedeutet moderne Führung? Ganz sicher liegen entscheidende Stellschrauben für nachhaltig gute Führung in den Bereichen Vertrauen, Transparenz, Offenheit. Aber eben auch bei Eigenverantwortung und Selbstorganisation: Moderne Führungskräfte, so kann man in jedem Seminar zum Thema hören, „moderieren“ die Kompetenzen anderer. Unternehmen. Klingt erstmal gut. Ist aber auch nicht wirklich neu – und macht eben auch Arbeit. Wer moderne Führungsansätze in seinem Unternehmen imple- mentieren möchte, kann diese nicht verordnen, sondern muss natürlich schwerpunktmäßig auf der persönlichen Einstellungsebene starten: Nur über Haltung und Einstellung glaubwürdiger, authentischer Führungskräfte lässt sich Verhaltensänderung in der Mannschaft erreichen. Und die braucht‘s, wenn sich das Unternehmen samt seiner Kultur wandeln soll. -

Research Report: Selected Case-Law of the European Court of Human Rights on Young People

RESEARCH REPORT _______________________ Selected case-law of the European Court of Human Rights on young people Publishers or organisations wishing to reproduce this report (or a translation thereof) in print or online are asked to contact [email protected] for further instructions. © Council of Europe/European Court of Human Rights, 2012 The document is available for downloading at www.echr.coe.int (Case-law – Case-Law Analysis – Research Reports). This document has been prepared by the Research Division and does not bind the Court. The text was finalised in November 2012, and may be subject to editorial revision. 2 COMPILATION OF RELEVANT CASE-LAW OF THE EUROPEAN COURT OF HUMAN RIGHTS ON YOUNG PEOPLE Compilation of Relevant Case-law of the European Court of Human Rights on Young People between 18 and 35 Years This compilation summarises the relevant case-law of the European Court of Human Rights on specific areas of importance for young people between 18 and 35 years: - Access to a professional career (under A.) ………………………………………….. 4 Bigaeva v. Greece, no. 26713/05, 28 May 2009 - Conscientious objection (under B.) …………………………………………………. 5 Savda v. Turkey, no. 42730/05, 12 June 2012 Bayatyan v. Armenia [GC], no. 23459/03, ECHR 2011 Thlimmenos v. Greece [GC], no. 34369/97, ECHR 2000-IV Koppi v. Austria, no. 33001/03, 10 December 2009 Gütl v. Austria, no. 49686/99, 12 March 2009 Löffelmann v. Austria, no. 42967/98, 12 March 2009 Ülke v. Turkey, no. 39437/98, 24 January 2006 Autio v. Finland, no. 17086/90, Commission decision of 6.12.1991 Johansen v. -

Young Adults in Nature-Based Services in Norway—In-Group and Between-Group Variations Related to Mental Health Problems

NJSR NORDIC JOURNAL of SOCIAL RESEARCH www.nordicjsr.net Young Adults in Nature-Based Services in Norway—In-Group and Between-Group Variations Related to Mental Health Problems Anne Mari Steigen* Faculty of Health and Social Sciences, Inland University of Applied Sciences Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, Karlstad University Email: [email protected] Bengt Eriksson Faculty of Health and Social Sciences, Inland University of Applied Sciences Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, Karlstad University Ragnfrid Eline Kogstad Faculty of Health and Social Sciences, Inland University of Applied Sciences Helge Prytz Toft Norwegian National Advisory Unit on Concurrent Substance Abuse and Mental Health Disorders, Innlandet Hospital Trust Institute of Clinical Medicine, University of Oslo Daniel Bergh Centre for Research on Child and Adolescent Mental Health, Karlstad University *Corresponding author Abstract Young adults with mental health problems who do not attend school or work constitute a significant welfare challenge in Norway. The welfare services available to these individuals include nature-based services, which are primarily located on farms and integrate the natural and agricultural environment into their daily activities. The aim of this study is to examine young adults (16–30 years old) not attending school or work who participated in nature-based services in Norway. In particular, the study analyses mental health problems among the participants and in-group variations regarding their symptoms of mental health problems using the Hopkins Symptoms Checklist (HSCL-10). This paper compares symptoms of mental health problems among participants in nature- NJSR – Nordic Journal of Social Research Vol 9, 2018 based services with those of a sample from the general population and a sample of those receiving clinical in-patient mental healthcare. -

Estonian Methodism During the First Year Under the Plague of the Red Commissars

Methodist History, 31:4 (July 1993) ESTONIAN METHODISM DURING THE FIRST YEAR UNDER THE PLAGUE OF THE RED COMMISSARS HEIGO RITSBEK "Immediately before the outbreak of World War II, Nazi Germany and Soviet Russia signed the Non-Aggression Pact of August 23, 1939, generally referred to as the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact. This treaty con tained secret provisions for dividing Eastern Europe into spheres of in fluence. "1 This pact is considered by many as one of the reasons for the onset of World War II. For Estonia, the Pact had terrible results. On June 17, 1940, Estonia was occupied by the Soviet Union. The Soviet secret police began to imprison and execute the population. The first mass deportation from Estonia to Soviet slave camps started on the night of June 13, 1941. Overnight, more than 10,000 people, including children and the elderly (or almost 1 percent of the population), were herded into overloaded box cars and taken away to remote areas in northern Russia and Siberia. These journeys often lasted several weeks under inhuman conditions, during which time a large number of deportees perished. Additionally, 1,741 people were later found in mass graves in Estonia. After the start of the Russian-German war on June 21, 1941, some 30,000 more Estonians were deported by the Soviets under the guise of conscription or were forced to leave Estonia to do slc>ve labor. All told, some 60,000 Estonians were arrested, murdered or deported during the first Soviet occupation 1940-1941.2 It is clear that under such circumstances, the Methodist Church in Estonia, which was founded by the missionary activities of the Methodist Episcopal Church in the United States of America, suffered very much.