Hope in the Dark

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sexuality, Blood, Imperialism and the Mytho-Celtic Origins of Dracula

Droch Fhola: Sexuality, Blood, Imperialism and the Mytho-Celtic Origins of Dracula Author: Joseph A Mendes Persistent link: http://hdl.handle.net/2345/399 This work is posted on eScholarship@BC, Boston College University Libraries. Boston College Electronic Thesis or Dissertation, 2005 Copyright is held by the author, with all rights reserved, unless otherwise noted. 1 Introduction: Dracula. Drac-ula . It is hard to ignore the menace in the name, the morbid delight one gets in pronouncing a name that is riddled with such meaning. At some level, human society is fascinated with the notion of a vampire: a revenant that ret urns from beyond the grave to extract the blood of the living in order to extend its unholy life. It plays on our basic fears as humans, the fear of the dead, the fear of dying, the fear of the unknown, and a fascination with this substance consisting of p lasma, platelets, and cells that runs through our veins. Bram Stoker took all of these fears to new heights when he wrote Dracula , one of the most enduring horror stories to ever be composed. The novel has generated enormous criticism that has chiefly been divided into the camps of Irishness, colonialism/imperialism, and sexuality. Whether it was intentional or not, Stoker’s novel is a breeding ground for almost every sexual fetish, deviance, and perversion that is known to mankind. Characters in the novel engage in mutilation, blood-drinking, perverted fellation, sexual acts in front of their spouse, female domination, male domination, group rape, homosexuality, male penetration, and sadomasochism. -

Smartilience Presentation

SMARTilience integrated monitoring model for the climate-resilient smart city 1 WHAT YOU WILL GET Insight into the topic of climate and resilience Contribute a tool that promotes climate-friendly work in cities (SMARTilience) Informations about transforming research Possibility to become a member of our Peer to Peer Insight into some projects in the area of civil protection 2 CLIMATE ADAPTATION Source: https://www.morgenstadt.de/de/projekte/aktuelle-projekte/innovationsprogramm_klimaneutrale_staedte.html 3 GOVERNANCE AND RESILIENCE “wide” definition of the governance term (see Mayntz 2004; Benz et al 2007 and Zürn 2008) "While the concept of control explicitly targets the control actions of political actors, the governance perspective deals with the institutional structure and its effects on the actions of the addresses (Trute et al 2008: 177)" (Stoy 2015: 34). Preparedness: dealing with possible climate impacts Recovery: probability to recover again 4 CORONA EFFECTS Comparison NO2 in Europe, source: https://www.dlr.de/content/de/artikel/news/2020/02/20200505_corona-effekt- auf-luftqualitaet-eindeutig.html 5 WHAT IS THE SMARTILIENCE PROJECT ABOUT? Promotion by o Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) o Funding measure "Flagship Initiative Zukunftsstadt“ Promoter o DLR German Aerospace Center e. V. Duration o 1-year definition phase (2017-2018) o 3-year research and development phase (2019-2022) Consortia: cities Halle and Mannheim, HafenCity University and University of Stuttgart, Drees&Sommer and Malik Management Gmbh 6 URBAN GOVERNANCE TOOLBOX The operation Development of a socio-technical control model for climate-resilient urban development (urban governance toolbox) Testing of the control model in the Halle (Saale) and Mannheim real-life laboratories The objective to support municipal decision-makers and actors* in taking efficient climate action 7 SMART TOOLS AND WORK PACKAGES Control, planning and implementation of climate protection and climate adaptation measures are data- based. -

1. PERSONAL DETAILS Piekkari, Maiden Name Marschan, Rebecca, Born 1967, Finnish Citizen, Researcher ID L-2736-2016, ORCHID 000-0002-4026-5850 2

1. PERSONAL DETAILS Piekkari, maiden name Marschan, Rebecca, born 1967, Finnish citizen, Researcher ID L-2736-2016, ORCHID 000-0002-4026-5850 2. EDUCATION AND DEGREES COMPLETED 10.5.1996 DSc (International Marketing, Helsinki School of Economics, Finland 27.5.1994 LSc (International Marketing), Helsinki School of Economics, Finland 25.5.1990 MSc (International Marketing, Helsinki School of Economics, Finland 3. CURRENT POSITION 2016– Head of International Business Unit, Aalto University School of Business, Finland 2004– Professor of International Business, Aalto University School of Business, Finland 4. PREVIOUS POSITIONS 2011–2015 Vice Dean, Research and International Relations, Aalto University School of Business 2007–2010 Head of International Business Unit, Aalto University School of Business 2002–2004 Research Fellow, Hanken School of Economics, Finland 2000–2000 Lecturer, University of Bath, School of Management, UK 1999–1999 Research Associate, Sheffield University Management School, UK 5. CAREER BREAKS 19.11.2000–1.12.2001 (12 months),19.1.2005–1.12.2007 (24 months) Maternity leave 6. PERSONAL RESEARCH FUNDING AND GRANTS 1.8.2014–31.7.2015 Sabbatical grants from Professoripooli (27 000e + 5 000e for travels); Marcus Wallenberg Foundation (10 000e); HSE Foundation (2 800e) 7. LEADERSHIP AND SUPERVISION EXPERIENCE Supervisor of post-doctoral researchers (5), Aalto University School of Business; Supervisor of doctoral dissertations as Committee Chair, Aalto University School of Business: Rauni Seppola (2004), Kristiina Mäkelä (2006), -

US Helsinki Commission

Commission on Security & Cooperation in Europe: U.S. Helsinki Commission “U.S. Priorities for Engagement at the OSCE” Committee Members Present: Senator Roger Wicker (R-MS), Co-Chairman; Senator Ben Cardin (D-MD), Ranking Member; Representative Joe Wilson (R-SC), Ranking Member; Senator John Boozman (R-AR); Senator Sheldon Whitehouse (D-RI); Representative Emanuel Cleaver, II (D-MO); Representative Marc Veasey (D-TX); Representative Richard Hudson (R-NC); Representative Sheila Jackson Lee (D-TX) Committee Staff Present: Rebecca Neff, State Department Senior Advisor, Commission for Security and Cooperation in Europe Witness: Ambassador Philip T. Reeker, Senior Bureau Official, U.S. Department of State The Hearing Was Held From 10:04 a.m. To 11:34 a.m. via Videoconference, Senator Ben Cardin (D-MD), Ranking Member, Commission for Security and Cooperation in Europe, presiding Date: Tuesday, December 8, 2020 Transcript By Superior Transcriptions LLC www.superiortranscriptions.com CARDIN: (In progress) I participated, Senator Wicker participated, I think Senator Hudson also participated in some of the side meetings that we’ve had during this period of time within the OSCE Parliamentary Assembly. And we had a meeting virtually to reaffirm our commitment to the OSCE moving forward. So, it was a commitment by parliamentarians from the OSCE states that we recognized we needed to do more. Last month we celebrated the 30th anniversary of the Charter of Paris. We had a Parliamentary Assembly gathering to help celebrate the Charter. It was the fall of the iron curtain that brought that about. And one of the great opportunities that I’ve had in my lifetime was to be in Berlin and actually take home a piece of the wall, and to see the fall of the iron curtain. -

Hollywood Pantages Theatre Los Angeles, California

® HOLLYWOOD PANTAGES THEATRE LOS ANGELES, CALIFORNIA PLAYBILL.COM 04-03 Love Never Dies Cover - Retro.indd 1 3/9/18 12:29 PM HOLLYWOOD PANTAGES THEATRE TROIKA ENTERTAINMENT PRESENTS Music Lyrics ANDREW LLOYD WEBBER GLENN SLATER Book BEN ELTON Based on The Phantom of Manhattan by FREDERICK FORSYTH Additional Lyrics CHARLES HART Orchestration DAVID CULLEN & ANDREW LLOYD WEBBER Starring GARDAR THOR CORTES MEGHAN PICERNO KATRINA KEMP RICHARD KOONS CASEY LYONS JAKE HESTON MILLER RACHEL ANNE MOORE BRONSON NORRIS MURPHY MARY MICHAEL PATTERSON STEPHEN PETROVICH SEAN THOMPSON and KAREN MASON Chelsey Arce, Erin Chupinsky, Diana DiMarzio, Tyler Donahue, Yesy Garcia, Alyssa Giannetti, Michael Gillis, Tamar Greene, Natalia Lepore Hagan, Lauren Lukacek, Alyssa McAnany, Dave Schoonover, Adam Soniak, John Swapshire IV, Kelly Swint, Lucas Thompson, Correy West, Arthur Wise Set & Costume Design Sound Design Lighting Design Wig & Hair Design GABRIELA TYLESOVA MICK POTTER NICK SCHLIEPER BACKSTAGE ARTISTRY Design Supervisor Technical Director Music Supervisor Casting by EDWARD PIERCE RANDY MORELAND KRISTEN BLODGETTE TARA RUBIN CASTING LINDSAY LEVINE, CSA Tour Booking, Press & Marketing Production Manager Music Coordinator General Manager BROADWAY BOOKING ANNA E. BATE DAVID LAI KAREN BERRY OFFICE NYC TALITHA FEHR Company Manager Music Director Production Stage Manager AARON QUINTANA DALE RIELING DANIEL S. ROSOKOFF Associate Director Executive Producer Associate Choreographer GAVIN MITFORD RANDALL A. BUCK SIMONE SAULT Choreographed by GRAEME MURPHY AO Directed -

Nora's Second Pre-Caucus

Party -D irecteD MeDiation : F acilitating Dialogue Between inDiviDuals gregorio BillikoPF , university of california ([email protected] , 209.525-6800) © 2014 regents of the university of california n o i t a r o p r o C l e r o C © 10 Nora’s Second Pre-Caucus the mediator opens with a general question about how things are going and then asks if nora has any feelings about the mediation process in which she has been participating. nora : things are fine . the process is fine. uh, rebecca was nice to me the other day. [laughing.] i was floored. it was wonderful! MeDiator : so, maybe there have been . nora : i think so. MeDiator : . some changes . already. nora : i think so. yeah. this type of improvement is typical in PDM, when there is more than one set of pre-caucuses, or when there is a lapse of time between these meetings and the joint session. the PDM process allows the parties to take some definitive steps toward reconciliation on their own. MeDiator : that has been the goal, but we haven’t brought you together, so hopefully . those steps can be taken . nora : yeah. we’ve had some pleasant exchanges, and that’s excellent. MeDiator : yes, well, good. if you don’t have anything else, i just want to go back, because it’s been a little over a 196 • Party -D ireCteD MeDiatioN month since we met, and review a few things with you. the mediator summarizes nora’s comments from her first pre- caucus. nora corrects a few notions but mostly agrees with the mediator’s understanding of the situation. -

Performance As a Master Narrative in Music History

Roundtable: Performance as a Master Narrative in Music History DANIEL BAROLSKY, SARA GROSS CEBALLOS, REBECCA PLACK, AND STEVEN M. WHITING The Editors or a Roundtable in this issue the Editors invited musicologists from various institutions to engage in an e-mail conversation with Daniel F Barolsky over the summer of 2012 to discuss the how music historians engage students with issues of performance in their classes. As Barolsky states in his opening essay “The music in our existing histories is restricted to past compositions, as mere museum artifacts. Yet the identities of the wonderful performers who brought these pieces to life (and many of whom we can still see and hear today!) are relegated to the liner notes, their presence and inter- pretive contribution repressed and ignored.” Are there ways we can enrich, transform, or adapt our teaching to focus more on a history of performance? Would such a change be more meaningful to our students, most of whom see themselves as young performers, rather than as young composers? What new questions, discussions, and course assignments would arise from such changes? The Editors invited musicologists who teach at a variety of schools (small liberal arts college, conservatories of various sizes and locations, and large state schools) to discuss the issue of teaching about music performance in music history courses and to share their thoughts and experiences about their work in this area. Daniel Barolsky began the conversation with an opening essay to which the panel responded by e-mail during the summer of 2012.1 Among the several threads that develop are questions about the choices for recordings of the score anthologies that accompany textbooks, the differences between teaching a survey for undergraduates and an advanced seminar, and teaching suggestions that address performance more clearly—such as 1. -

May 2016 in THIS ISSUE

Organized in 1969 and supported by churches, civic organizations, businesses, & individuals, CHO -- The Committee for Helping Others -- provides simple, loving charity to persons in need of goods and services which they are unable to provide for themselves or obtain from government services. May 2016 IN THIS ISSUE George's Corner George’s Corner: Mark Your Calendars: o Viva Vienna A reminder: It costs CHO approximately $1,000 a year to print and mail the 2 Newsletters to you. Your willingness to receive the o NFCU 5K Run/Walk Newsletters by email would enable our Emergency Services folks to o CROP Walk send 4 more $250 checks to supplement some of your more needy Needs neighbors' rent, utility, or doctor bills. The email version of the Briefs: Newsletter is in COLOR, and those who opt for the email version o Clothes Closet Summer will also receive more timely notices of our activities (no more than Closing once a quarter). o Furniture Program Summer Schedule If you no longer wish to receive a paper copy of the CHO Newsletter Thanks to our Donors in May and November, please let us know at [email protected], or by CHO Activities leaving a message on the CHO phone line 703-281-7614 (and don’t Fundraising/Food Collection forget to include your email address). Shortly after going into the Events: mail, a PDF version is available on our web site - www.cho-va.com. o SCOV Interfaith Service o Whole Foods Day Did you know? o Stuff the Bus Volunteer Award 1. You can provide a financial donation to CHO on our web Christmas Program Report page (cho-va.com) – see the Donate now! banner. -

Rebecca A. Kleinhample April 23, 2021 Executive Director

Club Meeting Speaker: Rebecca A. Kleinhample April 23, 2021 Oyster Point of Newport News Meets at During the COVID19 By Jeffery Andrew Trimbur on Wednesday, April 21, 2021 Shutdown, we are meeting via Zoom. Please email the president Executive Director, Virginia Living Museum for the link if you wish to join us. In August we anticipate we can resume meeting at Christopher Appointed Executive Director in December 2016, Kleinhample Newport University, David Student established a vision to reenergize natural science education Union. through exemplary guest experience and the highest standards 1 University Place of animal welfare at the Virginia Living Museum, taking the Newport News, VA Museum from where we�ve always been to where we need to Time: Friday at 07:30 AM be. Under Kleinhample�s leadership, the Museum is completing an aggressive strategic plan that increases program services and delights over 290,000 guests a year. She Events continues to drive financial sustainability through earned and contributed income, improved efficiencies with tight budgeting No Events found and data based decisions. At the heart of this community built, beloved, and sustained organization is a mission to connect people to nature through educational experiences that promote Speakers conservation. Kleinhample works to ensure the same for generations to come. The Museum serves as a community April 23, 2021 anchor, a priceless economic driver and resource to area Rebecca A. Kleinhample Executive residents and visiting tourists. By delivering Natural Science and Director, Virginia Living Museum Environmental Education through popular and fun hands-on live demonstrations, exhibits and programs for all ages, the Birthdays museum mission is even more relevant now as it was at the founding in 1966. -

Rebecca Macieira-Kaufmann

Rebecca Macieira-Kaufmann Rebecca Macieira-Kaufmann is a seasoned CEO with broad leadership experience in sales & marketing, risk management and international business operations, most recently at Citigroup and its subsidiaries. She brings deep expertise in the financial services industry and digitizing the consumer experience. With a demonstrated track record of leading highly successful business turnarounds, scaling new businesses and expanding operations globally, Macieira-Kaufmann also brings a strong background in governance through her corporate and non-profit board experiences. At The ExCo Group, she works with succession candidates, c-suite executives and senior leaders. In addition to her work at The ExCo Group, Macieira-Kaufmann currently serves on the Board of Governors of the San Francisco Symphony (Audit and Executive Committees) and on the Senior Jewish Living Group Board. Previously, Macieira-Kaufmann served on the board of Congregation Emanu-EI, CalChamber, and is the former President of JVS. She is a frequently sought-after speaker on leadership and business transformation, culture change and building high-performing teams. She has presented to business schools and organizations nationally. Macieira-Kaufmann spent over 11 years at Citigroup across a range of CEO, President and Managing Director roles, most recently serving as Head of Citigroup’s International Personal Bank. She managed a full P&L line of business serving the offshore wealth needs of multi-national clients in over 100 countries. From operations to marketing & sales, Macieira-Kaufmann was able to transform the business to avoid closure. She remediated the issues, simplified the operations and digitized the customer experience— growing the business exponentially and leaving it in strength. -

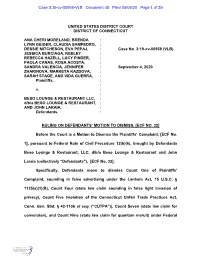

Case 3:19-Cv-00958-VLB Document 48 Filed 09/04/20 Page 1 of 39

Case 3:19-cv-00958-VLB Document 48 Filed 09/04/20 Page 1 of 39 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT DISTRICT OF CONNECTICUT ANA CHERI MORELAND, BRENDA : LYNN GEIGER, CLAUDIA SAMPEDRO, : DESSIE MITCHESON, EVA PEPAJ, : Case No. 3:19-cv-00958 (VLB) JESSICA BURCIAGA, KEELEY : REBECCA HAZELL, LUCY PINDER, : PAOLA CANAS, ROSA ACOSTA, : SANDRA VALENCIA, JENNIFER : September 4, 2020 ZHARINOVA, MARKETA KAZDOVA, : SARAH STAGE, AND VIDA GUERRA, : Plaintiffs, : : v. : : BESO LOUNGE & RESTAURANT LLC, : d/b/a BESO LOUNGE & RESTAURANT, : AND JOHN LARAIA, : Defendants. : RULING ON DEFENDANTS’ MOTION TO DISMISS, [ECF NO. 32] Before the Court is a Motion to Dismiss the Plaintiffs’ Complaint, [ECF No. 1], pursuant to Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 12(b)(6), brought by Defendants Beso Lounge & Restaurant, LLC, d/b/a Beso Lounge & Restaurant and John Laraia (collectively “Defendants”). [ECF No. 32]. Specifically, Defendants move to dismiss Count One of Plaintiffs’ Complaint, sounding in false advertising under the Lanham Act, 15 U.S.C. § 1125(a)(1)(B), Count Four (state law claim sounding in false light invasion of privacy), Count Five (violation of the Connecticut Unfair Trade Practices Act, Conn. Gen. Stat. § 42-110b et seq. (“CUTPA”)), Count Seven (state law claim for conversion), and Count Nine (state law claim for quantum meruit) under Federal Case 3:19-cv-00958-VLB Document 48 Filed 09/04/20 Page 2 of 39 Rule of Civil Procedure 12(b)(6) for failure to state claims upon which relief can be granted. [ECF No. 32-1 at 1-19]. Defendants also move to dismiss all claims of Plaintiffs Keeley Rebecca Hazell, Rosa Acosta, and Sandra Valencia as time-barred under the various applicable statutes of limitations. -

Daphne Du Maurier Chapter 1 Last Night I Dreamed I Went to Manderley

Rebecca: Daphne du Maurier Chapter 1 Last night I dreamed I went to Manderley* again. It seemed to me that I was passing through the iron gates that led to the driveway. The drive was just a narrow track now, its stony surface covered with grass and weeds. Sometimes, when I thought I had lost it, it would appear again, beneath a fallen tree or beyond a muddy 5 pool formed by the winter rains. The trees had thrown out new low branches which stretched across my way. I came to the house suddenly, and stood there with my heart beating fast and tears filling my eyes. There was Manderley, our Manderley, secret and silent as it had 10 always been, the grey stone shining in the moonlight of my dream. Time could not spoil the beauty of those walls, nor of the place itself, as it lay like a jewel in the hollow of a hand. The grass sloped down towards the sea, which was a sheet of silver lying calm under the moon, like a lake undisturbed by wind or storm. 15 I turned again to the house, and I saw that the garden had run wild, just as the woods had done. Weeds were everywhere. But moonlight can play strange tricks with the imagination, even with a dreamer’s imagination. As I stood there, I could swear that the house was not an empty shell, but lived and breathed as it had 20 lived before. Light came from the windows, the curtains blew softly in the night air, and there, in the library, the door stood half open as we had left it, with my handkerchief on the table beside the bowl of autumn flowers.