When It Comes to Racial Justice, Why Is It Wrong to Demand the "Impossible"?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Black Women As Activist Intellectuals: Ella Baker and Mae Mallory Combat Northern Jim Crow in New York City's Public Schools During the 1950S

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Publications and Research Hostos Community College 2019 Black Women as Activist Intellectuals: Ella Baker and Mae Mallory Combat Northern Jim Crow in New York City's Public Schools during the 1950s Kristopher B. Burrell CUNY Hostos Community College How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/ho_pubs/93 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] £,\.PYoo~ ~ L ~oto' l'l CILOM ~t~ ~~:t '!Nll\O lit.ti t~ THESTRANGE CAREERS OfTHE JIMCROW NORTH Segregation and Struggle outside of the South EDITEDBY Brian Purnell ANOJeanne Theoharis, WITHKomozi Woodard CONTENTS '• ~I') Introduction. Histories of Racism and Resistance, Seen and Unseen: How and Why to Think about the Jim Crow North 1 Brian Purnelland Jeanne Theoharis 1. A Murder in Central Park: Racial Violence and the Crime NEW YORK UNIVERSITY PRESS Wave in New York during the 1930s and 1940s ~ 43 New York www.nyupress.org Shannon King © 2019 by New York University 2. In the "Fabled Land of Make-Believe": Charlotta Bass and All rights reserved Jim Crow Los Angeles 67 References to Internet websites (URLs) were accurate at the time of writing. Neither the author nor New York University Press is responsible for URLs that may have expired or John S. Portlock changed since the manuscript was prepared. 3. Black Women as Activist Intellectuals: Ella Baker and Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Mae Mallory Combat Northern Jim Crow in Names: Purnell, Brian, 1978- editor. -

The Crusader Monthll,J Nelijsletter

THE CRUSADER MONTHLL,J NELIJSLETTER ROBERT F. WILLIAMS, EDITOR -IN EXILE- VoL . ~ - No. 9 MAY 1968 Afro-Americans & Slick John Kennedy Government of the United States is no government T~E of the Afro-Americans at all. The slick John Ken- nedy gang is operating one of the greatest sham govern- ment in the entire world. Afro-Americans and fair minded Od > ~- O THE wN«< /l~USL . lF Yov~Re EyER IN NE60, CALL ME AT whites must be gullible indeed to believe that the racist, KKK dominated so-called U.S. Government is concerned with the welfare and human rights of colored people. The colored people of the USA must bring themselves to realize that taken integration is a slick manuever to check the restlessness of an oppressed people fast becoming infect ed with the germ of total resistance policy developing among all of the oppressed peoples of the world. Token integration means nothing to the masses. Even an idiot should be able to see that so-called Token integration is no more than window dressing designed to lull the poor downtrodden Afro-American to sleep and to make the out side world think that the racist, savage USA is a fountainhead of social justice and democracy. The Afro-American in the USA is facing his greatest crisis since chattel slavery. All forms of violence and underhanded methods o.f extermination are being stepped up against our people. Contrary to what the "big daddies" and their "good nigras" would have us believe about all of the phoney progress they claim the race is making, the True status of the Afro-Ameri- can is s#eadily on the down turn. -

Emily J.H. Contois

Updated June 2021 EMILY J.H. CONTOIS 800 S. Tucker Drive, Department of Media Studies, Oliphant Hall 132, Tulsa, OK 74104 [email protected] | emilycontois.com | @emilycontois — EDUCATION — Ph.D. Brown University, 2018 American Studies with Gender & Sexuality Studies certificate, Advisor: Susan Smulyan M.A. Brown University, 2015 American Studies M.L.A. (Award for Excellence in Graduate Study), Boston University, 2013 Gastronomy, Thesis Advisor: Warren Belasco, Reader: Carole Counihan M.P.H. University of California, Berkeley, 2009 Public Health Nutrition B.A. (summa cum laude, Phi Beta Kappa), University of Oklahoma, 2007 Letters with Medical Humanities minor, Thesis Advisor: Julia Ehrhardt — APPOINTMENTS — Chapman Assistant Professor, Media Studies, The University of Tulsa, 2019-2022 Assistant Professor, Media Studies, The University of Tulsa, 2018-Present — PUBLICATIONS — Books 2020: Diners, Dudes, and Diets: How Gender and Power Collide in Food Media and Culture (University of North Carolina Press). Reviewed in: International Journal of Food Design (2021), Advertising & Society Quarterly (Author Meets Critics 2021), Men and Masculinities (2020), Library Journal (2020); Named one of Helen Rosner’s “Great Food-ish Nonfiction 2020;” Included on Civil Eats, “Our 2020 Food and Farming Holiday Book Gift Guide” and Food Tank’s “2020 Summer Reading List;” Featured in: Vox, Salon, Elle Paris, BitchMedia, San Francisco Chronicle, Tulsa World, Currant, BU Today, Culture Study, InsideHook, Nursing Clio Edited Collections 2022: {forthcoming} Food Instagram: Identity, Influence, and Negotiation, co-edited with Zenia Kish (University of Illinois Press). Refereed Journal Articles 2021: {forthcoming} “Real Men Don’t Eat Quiche, Do They? Food, Fitness, and Masculinity Crisis in 1980s America,” European Journal of American Culture’s 40th anniversary special issue. -

President's Report

· mount holyoke · PRESIDENT’S REPORT · a note from the · PRESIDENT The College has always been a place where big visions take shape. For over 180 years, we have opened opportunities for students to deepen their understanding and sharpen their response to a fast-changing world with challenges both known and unknown. We prepare students to learn and to lead because in life and work, we know this is what makes all the difference. Now that we have been deeply engaged in the work for two years of our five-year Plan for 2021, I’m delighted to share our progress, including an overview of some of Mount Holyoke’s new strategic initia- tives. In January 2018, we opened the Dining Commons, a part of the new Community Center, which is now also nearing completion. With the extensive renovations to Blanchard Hall we are creating a co-curricular hub in support of student leadership and programs, as well as a coffee shop and pub. We’ve also added new residential, co-curricular, and academic spaces. These spaces are the heart of our community-building efforts, giving more attention to shared endeavors and creating a sense of belonging. They represent a commitment to place at Mount Holyoke, reminding us all of the power of relationships that is in the very warp and woof of the College and the Alumnae Association. There is an energy and excitement to our being in the same space at the same times each day to eat, talk, think, and debate in companionship and cooperation. I hope the stories in these pages excite you about our current initi atives and our plans for the future. -

New Pathways in Civil Rights Historiography

Jeanne Theoharris, Komozi Woodard, eds.. Freedom North: Black Freedom Struggles Outside the South, 1940-1980. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2001. vii + 326 pp. $26.95, paper, ISBN 978-0-312-29468-7. Reviewed by Patrick Jones Published on H-1960s (June, 2005) A few weeks into my "Civil Rights Movement" point. I want to contest my students' ready no‐ seminar, I place a series of images on the over‐ tions of the movement as they think they know it. head projector. One shows a long, inter-racial pro‐ Over the remainder of the semester, we set off on cession of movement activists marching down a an academic adventure to develop a more compli‐ street lined with modest homes, lifting signs and cated understanding of white supremacy and singing songs. Another depicts a sneering young struggles for racial justice. white man stretching a large confederate fag. Yet Admittedly, this brief exercise is a bit cheap another portrays three angry white men, faces and gimmicky, but the visual trickery conveys an contorted in rage, holding a crudely scrawled sign important point that is not soon lost on my stu‐ with the words "white power." I ask my students dents: most of us have been taught to accept, un‐ to scan these images for clues that might unlock critically, a certain narrative of the civil rights their meaning. Of course, they have seen such movement. This narrative focuses mainly on the photos before, from Montgomery and Little Rock, South and privileges well-known leaders, non-vio‐ Birmingham and Selma, and invariably it is these lent direct action, integration, and voting rights. -

Confronting Antisemitism in Modern Media, the Legal and Political Worlds an End to Antisemitism!

Confronting Antisemitism in Modern Media, the Legal and Political Worlds An End to Antisemitism! Edited by Armin Lange, Kerstin Mayerhofer, Dina Porat, and Lawrence H. Schiffman Volume 5 Confronting Antisemitism in Modern Media, the Legal and Political Worlds Edited by Armin Lange, Kerstin Mayerhofer, Dina Porat, and Lawrence H. Schiffman ISBN 978-3-11-058243-7 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-067196-4 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-067203-9 DOI https://10.1515/9783110671964 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. For details go to https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Library of Congress Control Number: 2021931477 Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2021 Armin Lange, Kerstin Mayerhofer, Dina Porat, Lawrence H. Schiffman, published by Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston The book is published with open access at www.degruyter.com Cover image: Illustration by Tayler Culligan (https://dribbble.com/taylerculligan). With friendly permission of Chicago Booth Review. Printing and binding: CPI books GmbH, Leck www.degruyter.com TableofContents Preface and Acknowledgements IX LisaJacobs, Armin Lange, and Kerstin Mayerhofer Confronting Antisemitism in Modern Media, the Legal and Political Worlds: Introduction 1 Confronting Antisemitism through Critical Reflection/Approaches -

Concerned, Meet Terrified Intersectional Feminism and the Women's March

Women's Studies International Forum 69 (2018) 49–55 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Women's Studies International Forum journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/wsif Concerned, meet terrified: Intersectional feminism and the Women's March T ⁎ Sierra Brewer, Lauren Dundes Department of Sociology, McDaniel College, United States ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: The first US Women's March on January 21, 2017 seemingly had the potential to unite women across race. To Women's March assess the progress of feminism towards an increasingly intersectional feminist approach, the authors collected Trump and analyzed interview data from 20 young African American women who shared their impressions of the Clinton Women's March that followed Donald Trump's inauguration during the month after the march. Interviewees White feminism believed that Trump's election and his sexism spurred the march, prompting the participation of many women Intersectional feminism who had not previously embraced feminism. Interviewees suggested that the march provided white women with Pussy hat ff Race a means to protest the election rather than a way to address social injustice disproportionately a ecting lower Gender social classes and people of color. Interviewees believed that a racially inclusive feminist movement would Intersectionality remain elusive without a greater commitment to intersectional feminism. African American Introduction shaming of Latina Alicia Machado, crowned Miss Universe in 1996) (Chozick & Grynbaum, 2017). Indeed, the 2005 hot mic comment ap- “If I see that white folks are concerned, then people of color need to peared to be a principal focal point of the march for white women be terrified.” galvanized by Trump bragging that fame allowed him to be sexually In the above quotation, Women's March co-chair Tamika Mallory aggressive with women without their consent. -

Africa Latin America Asia 110101101

PL~ Africa Latin America Asia 110101101 i~ t°ica : 4 shilhnns Eurnna " fi F 9 ahillinnc Lmarica - .C' 1 ;'; Africa Latin America Asia Incorporating "African Revolution" DIRECTOR J. M . Verg6s EDITORIAL BOARD Hamza Alavi (Pakistan) Richard Gibson (U .S.A.) A. R. Muhammad Babu (Zanzibar) Nguyen Men (Vietnam) Amilcar Cabrera (Venezuela) Hassan Riad (U.A .R .) Castro do Silva (Angola) BUREAUX Britain - 4. Leigh Street, London, W. C. 1 China - A. M. Kheir, 9 Tai Chi Chang, Peking ; distribution : Guozj Shudian, P.O . Box 399, Peking (37) Cuba - Revolucibn, Plaza de la Revolucibn, Havana ; tel. : 70-5591 to 93 France - 40, rue Franqois lei, Paris 8e ; tel. : ELY 66-44 Tanganyika - P.O. Box 807, Dar es Salaam ; tel. : 22 356 U .S.A. - 244 East 46th Street, New York 17, N. Y. ; tel. : YU 6-5939 All enquiries concerning REVOLUTION, subscriptions, distribution and advertising should be addressed to REVOLUTION M6tropole, 10-11 Lausanne, Switzerland Tel . : (021) 22 00 95 For subscription rates, see page 240. PHOTO CREDITS : Congress of Racial Equality, Bob Adelman, Leroy McLucas, Associated Press, Photopress Zurich, Bob Parent, William Lovelace pp . 1 to 25 ; Leroy LcLucas p . 26 ; Agence France- Presse p . 58 ; E . Kagan p . 61 ; Photopress Zurich p . 119, 122, 126, 132, 135, 141, 144,150 ; Ghana Informa- tion Service pp . 161, 163, 166 ; L . N . Sirman Press pp . 176, 188 ; Camera Press Ltd, pp . 180, 182, 197, 198, 199 ; Photojournalist p . 191 ; UNESCO p . 195 ; J .-P . Weir p . 229 . Drawings, cartoons and maps by Sine, Strelkoff, N . Suba and Dominique and Frederick Gibson . -

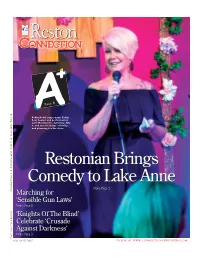

Restonreston

RestonReston Page 8 Robin Dodd (stage name Robin Rex) hosted and performed at Café Montmartre, Saturday, July 8, and was in charge of hiring and planning for the show. Classifieds, Page 10 Classifieds, ❖ RestonianRestonian BringsBrings Entertainment, Page 9 ❖ ComedyComedy toto LakeLake AnneAnne News,News, PagePage 33 Opinion, Page 4 MarchingMarching forfor ‘Sensible‘Sensible GunGun Laws’Laws’ News,News, PagePage 66 ‘Knights‘Knights OfOf TheThe Blind’Blind’ CelebrateCelebrate ‘Crusade‘Crusade AgainstAgainst Darkness’Darkness’ News,News, PagePage 33 Photo by Steve Broido www.ConnectionNewspapers.comJuly 19-25, 2017 online at www.connectionnewspapers.comReston Connection ❖ July 19-25, 2017 ❖ 1 South Lakes High School 2017 All Night Grad Party gratefully thanks our generous donors: Platinum ($500+) Emmert Family Harris Family FrozenYo Escape Room, Herndon Harvey Family Weber’s Pet Supermarket, Fox Mill Grealish Family Hawley Family Great Falls Area Ministries Hirshfeld Family Gold ($100 - 499) Hand & Stone Massage & Facial Spa Hughes Family Baser Family Harris Teeter, Spectrum Center Hunan East Restaurant Bond Family Harris Teeter, Woodland Crossing Irwin Family Chic Fil-A, Reston Jammula Family Jaeger Family Dlott Family Jersey Mike’s Subs, Reston Kanode Family Flippin’ Pizza, Reston Kalypso’s Sports Grill Karras Family Glory Days, Fox Mill & North Point Kong Family Kelly Family Golinsky Specific Chiropractic KSB Café of New York Konowe Family Greater Reston Arts Center King Pollo, Reston Kumar Family HoneyBaked Ham Lucia’s Italian Ristorante, -

Robert F. Williams, Negroes with Guns, Ch. 3-5, 1962

National Humanities Center Resource Toolbox The Making of African American Identity: Vol. III, 1917-1968 Robert F. Williams R. C. Cohen Negroes With Guns *1962, Ch. 3-5 Robert F. Williams was born and raised in Monroe, North Carolina. After serving in the Marine Cops in the 1950s, he returned to Monroe and in 1956 assumed leadership of the nearly defunct local NAACP chapter; within six months its membership grew from six to two-hundred. Many of the new members were, like him, military veterans trained in the use of arms. In the late 1950s the unwillingness of Southern officials to address white violence against blacks made it increasingly difficult for the NAACP to keep all of its local chapters committed to non-violence. In 1959, after three white men were acquitted of assaulting black women in Monroe, Williams publicly proclaimed the right of African Americans to armed self-defense. The torrent of criticism this statement brought down on the NAACP prompted its leaders — including Thurgood Marshall, Roy Wilkins, and Martin Luther King, Jr. — to denounce Williams. The NAACP eventually suspended him, but he continued to make his case for self-defense. Williams in Tanzania, 1968 Chapter 3: The Struggle for Militancy in the NAACP Until my statement hit the national newspapers the national office of the NAACP had paid little attention to us. We had received little help from them in our struggles and our hour of need. Now they lost no time. The very next morning I received a long distance telephone call from the national office wanting to know if I had been quoted correctly. -

Mae Mallory Papers

THE MAE MALLORY COLLECTION Papers, 1961-1967 (Predominantly, 1962-1963) 1 linear foot Accession Number 955 L.C. Number The papers of Mae Mallory were placed in the Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs in January of 1978 by General Baker and were opened for research in December of 1979. Mae Mallory (also known as Willie Mae Mallory) was born in Macon, Georgia on June 9, 1927. She later went to live in New York City with her mother in 1939. She became active in the black civil rights movement and was secretary of the organization, Crusaders for Freedom. She was closely associated with the ultra-militant leader of the NAACP chapter in Monroe, North Carolina, Robert F. Williams, who advocated that blacks arm them- selves in order to defend their rights. In 1961 she, Williams and others were charged with kidnap pong a white couple during a racial disturbance in Monroe. She fled to Cleveland, Ohio, to avoid arrest, but was imprisoned from 1962 to 1964 in the Cuyahoga County Jail to await extradition to North Carolina to face trial. Williams, who, like Mallory, protested his innocence of the charges, fled via Canada to Cuba and later China. In 1964 she was returned to Monroe, stood trial, and was convicted. She appealed the sentence, and in the following year the North Carolina Supreme Court dismissed the case because blacks had been excluded from the grand jury. The material in this collection reflects Mallory's participation in the civil rights movement and documents her period of imprisonment. Important subjects covered in the collection are: Black activism (1960's) Civil rights movement Monroe Defense Committee Revolutionary Action Movement (RAM) Robert F. -

Women's March, Like Many Before It, Struggles for Unity

Women’s March, Like Many Before It, Struggles for Unity - Not Even Past BOOKS FILMS & MEDIA THE PUBLIC HISTORIAN BLOG TEXAS OUR/STORIES STUDENTS ABOUT 15 MINUTE HISTORY "The past is never dead. It's not even past." William Faulkner NOT EVEN PAST Tweet 0 Like THE PUBLIC HISTORIAN Women’s March, Like Many Before It, Struggles for Unity Making History: Houston’s “Spirit of the Originally posted on the blog of The American Prospect, January 6, 2017. Confederacy” By Laurie Green For those who believe Donald Trump’s election has further legitimized hatred and even violence, a “Women’s March on Washington” scheduled for January 21 offers an outlet to demonstrate mass solidarity across lines of race, religion, age, gender, national identity, and sexual orientation. May 06, 2020 More from The Public Historian BOOKS America for Americans: A History of Xenophobia in the United States by Erika Lee (2019) April 20, 2020 More Books The 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom (The Center for Jewish History via Flickr) The idea of such a march first ricocheted across social media just hours after the TV networks called the DIGITAL HISTORY election for Trump, when a grandmother in Hawaii suggested it to fellow Facebook friends on the private, pro-Hillary Clinton group page known as Pantsuit Nation. Millions of postings later, the D.C. march has mushroomed to include parallel events in 41 states and 21 cities outside the United States. An Más de 72: Digital Archive Review independent national organizing committee has stepped in to articulate a clear mission and take over https://notevenpast.org/womens-march-like-many-before-it-struggles-for-unity/[6/19/2020 8:58:41 AM] Women’s March, Like Many Before It, Struggles for Unity - Not Even Past logistics.