Articles Sting Victims: Third-Party Harms In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Queer Expertise: Urban Policing and the Construction of Public Knowledge About Homosexuality, 1920–1970

Queer Expertise: Urban Policing and the Construction of Public Knowledge About Homosexuality, 1920–1970 The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Lvovsky, Anna. 2015. Queer Expertise: Urban Policing and the Construction of Public Knowledge About Homosexuality, 1920–1970. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University, Graduate School of Arts & Sciences. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:17463142 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Queer Expertise: Urban Policing and the Construction of Public Knowledge about Homosexuality, 1920–1970 A dissertation presented by Anna Lvovsky to The Committee on Higher Degrees in the History of American Civilization in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of History of American Civilization Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts May 2015 © 2015 – Anna Lvovsky All rights reserved. Advisor: Nancy Cott Anna Lvovsky Queer Expertise: Urban Policing and the Construction of Public Knowledge about Homosexuality, 1920–1970 Abstract This dissertation tracks how urban police tactics against homosexuality participated in the construction, ratification, and dissemination of authoritative public knowledge about gay men in the -

The Undercover Manual for Law Enforcement

UNDERCOVER MANUAL POLICY MANUAL RESTRICTED FOR LAW ENFORCEMENT RESTRICTED FOREWORD .................................................................................................................. 5 HOW TO USE THE MANUAL ..................................................................................... 13 Manual Structure ........................................................................................................ 13 Policy.............................................................................................................. 13 Procedures ...................................................................................................... 13 Cross References ............................................................................................ 13 GENERAL ...................................................................................................................... 14 Undercover Policing ................................................................................................... 14 Purpose........................................................................................................... 14 Scope .............................................................................................................. 15 Definitions.................................................................................................................. 15 Undercover Agent .......................................................................................... 15 Handler.......................................................................................................... -

Water-Saving Ideas Rejected at Meeting

THE TWEED SHIRE Volume 2 #15 Thursday, December 10, 2009 Advertising and news enquiries: Phone: (02) 6672 2280 Our new Fax: (02) 6672 4933 property guide [email protected] starts on page 19 [email protected] www.tweedecho.com.au LOCAL & INDEPENDENT Water-saving ideas Restored biplane gets the thumbs up rejected at meeting Luis Feliu years has resulted in new or modified developments having rainwater tanks Water-saving options for Tweed resi- to a maximum of 3,000 litres but re- dents such as rainwater tanks, recy- stricted to three uses: washing, toilet cling, composting toilets as well as flushing and external use. Rainwater population caps were suggested and tanks were not permitted in urban rejected at a public meeting on Mon- areas to be used for drinking water day night which looked at Tweed Some residents interjected, saying Shire Council’s plan to increase the that was ‘absurd’ and asked ‘why not?’ shire’s water supply. while others said 3,000 litres was too Around 80 people attended the small. meeting at Uki Hall, called by the Mr Burnham said council’s water Caldera Environment Centre and af- demand management strategy had fected residents from Byrrill Creek identified that 5,000-litre rainwater concerned about the proposal to dam tanks produced a significant decrease their creek, one of four options under in overall demand but council had no discussion to increase the shire’s water power to enforce their use. supply. The other options are rais- Reuse not explored Nick Challinor, left, and Steve Searle guide the Tiger -

United States Trustee Program FY 2014 Budget Request

United States Trustee Program FY 2014 Budget Request March 6, 2013 Table of Contents Page Number I. Overview A. Background ...................................................................................................... 7 B. Full Program Costs .......................................................................................... 8 C. Performance Challenges .................................................................................. 8 1. Bankruptcy Filings ..................................................................................... 9 2. U.S. Trustee System Fund .......................................................................... 10 D. Revenue Estimates ........................................................................................... 11 E. Environmental Management Systems Implementation .................................... 13 II. Summary of Program Changes ............................................................................. 13 III. Appropriations Language and Analysis of Appropriations Language ............. 13 IV. Decision Unit Justification Administration of Cases ........................................................................................ 14 1. Program Description ............................................................................ 15 2. Performance Tables .............................................................................. 23 3. Data Definition, Validation, Verification and Limitations .................. 24 4. Performance, Resources, and Strategies ............................................. -

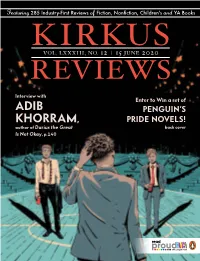

Kirkus Reviews

Featuring 285 Industry-First Reviews of Fiction, Nonfiction, Children'sand YA Books KIRKUSVOL. LXXXIII, NO. 12 | 15 JUNE 2020 REVIEWS Interview with Enter to Win a set of ADIB PENGUIN’S KHORRAM, PRIDE NOVELS! author of Darius the Great back cover Is Not Okay, p.140 with penguin critically acclaimed lgbtq+ reads! 9780142425763; $10.99 9780142422939; $10.99 9780803741072; $17.99 “An empowering, timely “A narrative H“An empowering, timely story with the power to experience readers won’t story with the power to help readers.” soon forget.” help readers.” —Kirkus Reviews —Kirkus Reviews —Kirkus Reviews, starred review A RAINBOW LIST SELECTION WINNER OF THE STONEWALL A RAINBOW LIST SELECTION BOOK AWARD WINNER OF THE PRINTZ MEDAL WINNER OF THE PRINTZ MEDAL 9780147511478; $9.99 9780425287200; $22.99 9780525517511; $8.99 H“Enlightening, inspiring, “Read to remember, “A realistic tale of coming and moving.” remember to fight, fight to terms and coming- —Kirkus Reviews, starred review together.” of-age… with a touch of —Kirkus Reviews magic and humor” A RAINBOW LIST SELECTION —Kirkus Reviews Featuring 285 Industry-First Reviews of Fiction, Nonfiction, Children’s,and YA Books. KIRKUSVOL. LXXXVIII, NO. 12 | 15 JUNE 2020 REVIEWS THE PRIDEISSUE Books that explore the LGBTQ+ experience Interviews with Meryl Wilsner, Meredith Talusan, Lexie Bean, MariNaomi, L.C. Rosen, and more from the editor’s desk: Our Books, Ourselves Chairman HERBERT SIMON BY TOM BEER President & Publisher MARC WINKELMAN John Paraskevas # As a teenager, I stumbled across a paperback copy of A Boy’s Own Story Chief Executive Officer on a bookstore shelf. Edmund White’s 1982 novel, based loosely on his MEG LABORDE KUEHN [email protected] coming-of-age, was already on its way to becoming a gay classic—but I Editor-in-Chief didn’t know it at the time. -

Understanding and Overcoming the Entrapment Defense in Undercover Operations

1 Understanding and Overcoming the Entrapment Defense in Undercover Operations Understanding and Overcoming the Entrapment Defense in Undercover Operations Sgt. Danny Baker Fort Smith Police Department Street Crimes Unit 2 Understanding and Overcoming the Entrapment Defense in Undercover Operations Introduction: Perhaps one of the most effective, yet often misunderstood investigatory tools available to law enforcement agencies around the world is that of the undercover agent. In all other aspects of modern policing, from traffic enforcement to homicide investigation, policing technique relies heavily upon the recognition and identification of an agent as an officer of the law. Though coming under question in recent years, it has long been professed that highly visible police have a deterrent effect on crime simply by their presence. Simply stated, the belief is that a criminal intent on breaking the law will likely refrain from doing so should he or she encounter, or have a high likelihood of encountering, a uniformed police officer just moments prior to the intended crime. Such presence certainly has its benefits in a civilized society. If to no other end, the calming and peace of mind that highly visible and accessible officers provide the citizenry is invaluable. The real dilemma arises when attempting to justify and fund this police presence that crime ridden neighborhoods and communities continually demand. Particularly when the crime suppression benefits of such tactics are questionable and impossible to measure. After all, how do you quantify the number of crimes that were never committed and, if you could, how do you correlate that to simple police presence? In polar opposition to the highly visible, readily accessible, uniformed officer, we find the undercover officer. -

Criminal Prosecutions and the 2008 Financial Crisis in the US and Iceland

Concordia Law Review Volume 4 | Number 1 Article 5 2019 Criminal Prosecutions and the 2008 Financial Crisis in the U.S. and Iceland: What Can a Small Town Icelandic Police Chief Teach the U.S. about Prosecuting Wall Street? Justin Rex Bowling Green State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.cu-portland.edu/clr Part of the Banking and Finance Law Commons CU Commons Citation Rex, Justin (2019) "Criminal Prosecutions and the 2008 Financial Crisis in the U.S. and Iceland: What Can a Small Town Icelandic Police Chief Teach the U.S. about Prosecuting Wall Street?," Concordia Law Review: Vol. 4 : No. 1 , Article 5. Available at: https://commons.cu-portland.edu/clr/vol4/iss1/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Law at CU Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Concordia Law Review by an authorized editor of CU Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CRIMINAL PROSECUTIONS AND THE 2008 FINANCIAL CRISIS IN THE U.S. AND ICELAND: WHAT CAN A SMALL TOWN ICELANDIC POLICE CHIEF TEACH THE U.S. ABOUT PROSECUTING WALL STREET? JUSTIN REX* Politicians, journalists, and academics alike highlight the paucity of criminal prosecutions for senior financial executives in the United States in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis. One common argument for the lack of prosecutions is that, though industry players behaved recklessly, they did not behave criminally. This Article evaluates this claim by detailing the civil and small number of criminal actions actually taken, and by reviewing leading arguments about whether behavior before the crisis was criminal. -

Combating Illicit Drug Trafficking by Undercover Operations by Mr

COMBATING ILLICIT DRUG TRAFFICKING BY UNDERCOVER OPERATIONS Wasawat Chawalitthamrong* I. INTRODUCTION Drug crime is a major problem facing every society in the world at present. They are different from the past by having secretly specialized and complicated systems. New technology techniques are used as tools, and drug crime is committed in systematic ways and in networks which involve organized crime and transnational crime, causing severe damage and effects on society, economics, politics and national security. Investigation cannot lead to offenders so efficient special investigation is needed to be used for wiretapping, intercepts, undercover operations, and controlled delivery. Special investigation plays a very important role in suppressing and convicting offenders. To understand how to handle organized crime and drug dealers, the comprehension of laws, investigation systems and techniques of drug crime investigation are necessary. Moreover, creating networks for information exchange and joint investigation will be the permanent solution and drug crime prevention. II. CHAPTER ONE A. Investigation Principles and Techniques of Drug Crime Investigation Drug crime is different from other crimes since it is committed by a group of people engaged in organized crime and by secretly specialized and complicated systems. Normal investigation cannot lead to a drug lord. The drug lord always avoids prosecution and conviction due to the lackof evidence such as drugs and money from drug dealings, except for money from money laundering. Collecting evidence and judicial proceedings with offenders need effective investigative techniques that are different form general crime suppression. To operate systematically and efficiently, undercover operations are the best solution for drug crime and for obtaining justice. -

Cape Coral Daily Breeze

Unbeaten no more CAPE CORAL Cape High loses match to Fort Myers DAILY BREEZE — SPORTS WEATHER: Partly Sunny • Tonight: Mostly Clear • Saturday: Partly Sunny — 2A cape-coral-daily-breeze.com Vol. 48, No. 53 Friday, March 6, 2009 50 cents Jury recommends life in prison for Fred Cooper “They’re the heirs to this pain. They’re the ones who Defense pleads for children’s sake want answers. They’re the ones who will have questions. If we kill him, there will be no answers, there will be no By STEVEN BEARDSLEY Cooper on March 16. recalled the lives of the victims, a resolution, there will be nothing.” Special to the Breeze Cooper, 30, convicted of killing young Gateway couple that doted on The state should spare the life of Steven and Michelle Andrews, both their 2-year-old child, and the trou- — Beatriz Taquechel, defense attorney for Fred Cooper convicted murderer Fred Cooper, a 28, showed little reaction to the bled childhood of the convicted, majority of Pinellas County jurors news, despite an emotional day that who grew up without his father and at times brought him to tears. got into trouble fast. stood before jurors and held their “They’re the heirs to this pain. recommended Thursday. pictures aloft, one in each hand. One They’re the ones who want Lee County Judge Thomas S. Jurors were asked to weigh the In the end, the argument for case for Cooper’s death with a pas- Cooper’s life was the lives of the was of the Andrewses’ 2-year-old answers,” Taquechel pleaded. -

Two Family Members Die in I-80 Rollover

FRONT PAGE A1 www.tooeletranscript.com TUESDAY TOOELE RANSCRIPT Two local players T compete against each other at college level See A9 BULLETIN October 2, 2007 SERVING TOOELE COUNTY SINCE 1894 VOL. 114 NO. 38 50¢ Two family members die in I-80 rollover by Suzanne Ashe injured in the wreck. He was victims to the hospital. STAFF WRITER one of seven people who were Jose Magdeleno, 9, Yadira thrown from the vehicle when it Miranda, 5, and Amie Cano, Two members of the same rolled several times. 5, were all flown to Primary family died as a result of a The car was speeding when it Children’s Hospital. crash near Delle on I-80 Sunday drifted to the left before Cano- Gutierrez said the family may night. Magdeleno overcorrected to the have been coming back from According to Utah Highway right and the car went off the Wendover. Patrol Trooper Sgt. Robert road, Gutierrez said. All eastbound lanes were Gutierrez, the single-vehicle Cano-Magdeleno’s wife, closed for about an hour after rollover occurred at 7:20 p.m. Roxanna Guatalupe Miranda, the accident, and lane No. 2 was near mile post 69. 22, and the driver’s daugh- closed for about three hours. Gutierrez said alcohol was ter Emily Cano, 10 were killed. Gutierrez said no one in the a factor, and open containers Dalila Marisol Cano, 39, is in two-door 1988 Ford Escort was were found at the scene. critical condition. wearing a seat belt. Photo courtesy of Utah Highway Patrol The driver, Jose J. -

Guidelines on Undercover Operations

Guidelines on Undercover Operations June 18, 2013 PREAMBLE These Guidelines on the use of undercover operations by Offices of Inspector General (OIGs) apply to those offices of Inspectors General with law enforcement powers received from the Attorney General under section 6(e) of the Inspector General Act of 1978, as amended, 1Any of the individual Offices of Inspector General that comprise the OIGs will be referred to in these Guidelines as an "OIG," 1 See Attorney General Guidelines for Offices of Inspector General with Statutory Law Enforcement Authority, Section III. TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................ 1 II. DEFINITIONS ............................................................................................................................ 1 A. UNDERCOVER ACTIVITIES ........................................................................................ 1 B. UNDERCOVER OPERATIONS ...................................................................................... 1 C. UNDERCOVER EMPLOYEE ......................................................................................... 1 D. IG UNDERCOVER REVIEW COMMITTEE ................................................................. 1 E. PROPRIETARY ................................................................................................................ 2 F. DESIGNATED PROSECUTOR ...................................................................................... -

If You Have Issues Viewing Or Accessing This File, Please Contact Us at NCJRS.Gov

If you have issues viewing or accessing this file, please contact us at NCJRS.gov. j, ., . DEVELOPING AND USING UNDERWORLD POLICE INFORMANTS Howard A. Katz I: Regional Law Enforcement Training Center COLLEGE OF THE MAINLAND Texas City, Texas = 7 DEVELOPING AND USING UNDERWORLD POLICE INFORMANtS TABLE OF CONTENTS In troduc tion ........................ I\: •••••• 1(1 ................. \I .......... ii Narcotics Investigations: Developing and Using Informants •••••••••••• 1 The Use of Juveniles as Police InformantB ..••.••••••••.••••••••••••• 13 The Use of Probationers and Parolees as Police Info~lants •••••.••••. 19 Appendix A - Confidential Informant File Form •••.••.•••••••••••••••• 29 Appendix B - Fiscal Accountability Forms .•••.••••••••••••••••••••••• 31 i INTRODUCTION The IiU,nderworld Informant" i·s a person who is engaged in criminal activities or who, if not so engaged, maintains a close relationship with persons involved in crime and vice activities, Their use by the police for the purpose of conducting investigations has always been quite contro- versial. The American public, by and large, has a strong belief in "fair play" and the use of such informants is generally considered as being somewhat unfair to persons under investigation. Furthermore, civil liber- tarians believe that the use of underworld informants, especially in vice and narcotics investigations, lends itt;lelf to the entrapment of the persons under investigation, a violation of their constitutional rights. Finally, the prosecution's case may be tainted in the eyes of a jury whenever an underworld informant played a substantial role in the investigatory process, since the defense attorney will almost surely lead the jurors to suspect that the informer was permitted to continue his crimimll .ectivities during the course of the investigation.