Knowles 2018 Wandi Oldmusi

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

16 Exhibition on Screen

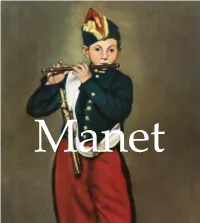

Exhibition on Screen - The Impressionists – And the Man Who Made Them 2015, Run Time 97 minutes An eagerly anticipated exhibition travelling from the Musee d'Orsay Paris to the National Gallery London and on to the Philadelphia Museum of Art is the focus of the most comprehensive film ever made about the Impressionists. The exhibition brings together Impressionist art accumulated by Paul Durand-Ruel, the 19th century Parisian art collector. Degas, Manet, Monet, Pissarro, Renoir, and Sisley, are among the artists that he helped to establish through his galleries in London, New York and Paris. The exhibition, bringing together Durand-Ruel's treasures, is the focus of the film, which also interweaves the story of Impressionism and a look at highlights from Impressionist collections in several prominent American galleries. Paintings: Rosa Bonheur: Ploughing in Nevers, 1849 Constant Troyon: Oxen Ploughing, Morning Effect, 1855 Théodore Rousseau: An Avenue in the Forest of L’Isle-Adam, 1849 (Barbizon School) Jean-François Millet: The Gleaners, 1857 (Barbizon School) Jean-François Millet: The Angelus, c. 1857-1859 (Barbizon School) Charles-François Daubigny: The Grape Harvest in Burgundy, 1863 (Barbizon School) Jean-François Millet: Spring, 1868-1873 (Barbizon School) Jean-Baptiste Camille Corot: Ruins of the Château of Pierrefonds, c. 1830-1835 Théodore Rousseau: View of Mont Blanc, Seen from La Faucille, c. 1863-1867 Eugène Delecroix: Interior of a Dominican Convent in Madrid, 1831 Édouard Manet: Olympia, 1863 Pierre Auguste Renoir: The Swing, 1876 16 Alfred Sisley: Gateway to Argenteuil, 1872 Édouard Manet: Luncheon on the Grass, 1863 Edgar Degas: Ballet Rehearsal on Stage, 1874 Pierre Auguste Renoir: Ball at the Moulin de la Galette, 1876 Pierre Auguste Renoir: Portrait of Mademoiselle Legrand, 1875 Alexandre Cabanel: The Birth of Venus, 1863 Édouard Manet: The Fife Player, 1866 Édouard Manet: The Tragic Actor (Rouvière as Hamlet), 1866 Henri Fantin-Latour: A Studio in the Batingnolles, 1870 Claude Monet: The Thames below Westminster, c. -

Class 3: the Impressionist Revolution

Class 3: The Impressionist Revolution A. Who were they? 1. Title Slide 1 (Renoir: The Skiff) 2. Revolution/Legacy Last week was most about poetry. Today, will be almost all about painting. I had originally announced it as “The Impressionist Legacy,” with the idea that I was take the actual painters—Monet, Renoir, and the like—for granted and spend the whole class on their legacy. But the more I worked, the more I saw that the changes that made modernism possible all occurred in the work of the Impressionists themselves. So I have changed the title to “The Impressionist Revolution,” and have tweaked the syllabus to add a class next week that will give the legacy the time it needs. 3. Monet: Impression, Sunrise (1872, Paris, Musée Marmottan) So who were the Impressionists? The name is the easy part. At the first group exhibition in 1874, Claude Monet (1840–1926) showed a painting of the port in his home town of Rouen, and called it Impression, Sunrise. A hostile critic seized on the title as an instrument of ridicule. But his quip backfired; within two years, the artists were using the name Impressionistes to advertise their shows. 4. Chart 1: artists before the first Exhibition 5. Chart 2: exhibition participation There were eight group exhibitions in all: in 1874, 1876, 1877, 1879, 1880, 1881, 1882, and 1886. So one answer to the question “Who were the Impressionists?” would be “Anyone who participated in one or more of their shows.” Here are seven who did, with a thumbnail of their earlier work, plus two who didn’t. -

Berthe Morisot and Mary Cassatt. Jessica Cresseveur University of Louisville

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 5-2016 The queer child and haut bourgeois domesticity : Berthe Morisot and Mary Cassatt. Jessica Cresseveur University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Part of the American Art and Architecture Commons, Modern Art and Architecture Commons, and the Theory and Criticism Commons Recommended Citation Cresseveur, Jessica, "The queer child and haut bourgeois domesticity : Berthe Morisot and Mary Cassatt." (2016). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 2409. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/2409 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The nivU ersity of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The nivU ersity of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE QUEER CHILD AND HAUT BOURGEOIS DOMESTICITY: BERTHE MORISOT AND MARY CASSATT By Jessica Cresseveur B.A., University of Louisville, 2000 M.A., University College London, 2003 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of the University of Louisville in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Humanities Department of Comparative Humanities University -

Dossier Pédagogique | Le Nain Created

Exposition / 22 mars - 26 juin 2017 LE MYSTÈRE LE NAIN DOSSIER PÉDAGOGIQUE 1 Exposition : Crédits photographiques : Commissariat : NICOLAS M ILOVANOVIC , conservateur en chef, département Couverture © RMN-GP (musée du Louvre) / Mathieu Rabeau SOMMAIRE des Peintures, musée du Louvre P. 4-5 © The National Gallery, Londres, Dist. RMN-GP / National Gallery LUC P IRALLA , conservateur, musée du Louvre-Lens Photographic Department P. 6 © RMN-GP (musée du Louvre) / Mathieu Rabeau Directeur de publication : P. 7 (de haut en bas, 1 et 2) © RMN-GP (musée du Louvre) / Jean-Gilles MARIE LAVANDIER, directrice, musée du Louvre-Lens Berizzi P. 7 (de haut en bas, 3) © RMN-GP (musée du Louvre) / Mathieu Rabeau ÉDITO 4 Responsable éditoriale : P. 7 (de haut en bas, 4) © RMN-GP / Daniel Arnaudet JULIETTE G UÉPRATTE , chef du service des Publics, musée du Louvre-Lens P. 8 © National Gallery of Art P. 9 © State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia / Peter Willi / Coordination : Bridgeman Images INTRODUCTION 6 EVELYNE REBOUL , chargée des actions éducatives, musée du Louvre-Lens P. 10 © RMN-GP (musée du Louvre) / Michel Urtado GAUTIER VERBEKE, responsable de la médiation, musée du Louvre-Lens P. 12 © RMN-GP (musée du Louvre) / Mathieu Rabeau JEANNE-THÉRÈSE BONTINCK , médiatrice, musée du Louvre-Lens P. 13 (haut) © RMN-GP (musée du Louvre) / Franck Raux PARTIE 1 : QUI LES FRÈRES LE NAIN PEIGNENTKILS ? 6 P. 13 (bas) © The National Gallery, Londres, Dist. RMN-GP / National Conception : Gallery Photographic Department I. D ES DÉTAILS INTRIGANTS 6 JEANNE-THÉRÈSE BONTINCK , médiatrice, musée du Louvre-Lens P. 14 © RMN-GP (musée Picasso de Paris) / Jean-Gilles Berizzi II. -

Chapter 25 Baroque

CHAPTER 25 BAROQUE Flanders, Dutch Republic, France,,g & England Flanders After Marti n Luth er’ s Re forma tion the region of Flanders was divided. The Northern half became the Dutch Republic, present day Holland The southern half became Flanders, Belgium The Dutch Republic became Protestant and Flanders became Catholic The Dutch painted genre scenes and Flanders artists painted religious and mythol ogi ca l scenes Europe in the 17th Century 30 Years War (1618 – 1648) began as Catholics fighting Protestants, but shifted to secular, dynastic, and nationalistic concerns. Idea of united Christian Empire was abandoned for secu lar nation-states. Philip II’s (r. 1556 – 1598) repressive measures against Protestants led northern provinces to break from Spain and set up Dutch Republic. Southern Provinces remained under Spanish control and retained Catholicism as offiilfficial re liiligion. PlitildititiPolitical distinction btbetween HlldHolland an dBlid Belgium re fltthiflect this or iiigina l separation – religious and artistic differences. 25-2: Peter Paul Rubens, Elevation of the Cross, 1610-1611, oil on Cue Card canvas, 15 X 11. each wing 15 X 5 • Most sought a fter arti st of hi s time - Ambassador, diplomat, and court painter. •Paintinggy style •Sculptural qualities in figures •Dramatic chiaroscuro •Color and texture like the Venetians • Theatrical presentation like the Italian Baroque •Dynamic energy and unleashed passion of the Baroque •Triptych acts as one continuous space across the three panels. •Rubens studied Renaissance and Baroque works; made charcoal drawings of Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel and the Laocoon and his 2 sons. •Shortly after returning home , commissioned by Saint Walburga in Antwerp to paint altarpiece – Flemish churches affirmed their allegiance to Catholicism and Spanish Hapsburg role after Protestant iconoclasm in region. -

L-G-0000349593-0002314995.Pdf

Manet Page 4: Self-Portrait with a Palette, 1879. Oil on canvas, 83 x 67 cm, Mr et Mrs John L. Loeb collection, New York. Designed by: Baseline Co Ltd 127-129A Nguyen Hue, Floor 3, District 1, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam © Sirrocco, London, UK (English version) © Confidential Concepts, worldwide, USA All rights reserved No part of this publication may be reproduced or adapted without the permission of the copyright holder, throughout the world. Unless otherwise specified, copyrights on the works reproduced lies with the respective photographers. Despite intensive research, it has not always been possible to establish copyright ownership. Where this is the case we would appreciate notification ISBN 978-1-78042-029-5 2 “He was greater than we thought he was.” — Edgar Degas 3 Biography 1832: Born Edouard Manet 23 January in Paris, France. His father is Director of the Ministry of Justice. Edouard receives a good education. 1844: Enrols into Rollin College where he meets Antonin Proust who will remain his friend throughout his life. 1848: After having refused to follow his family’s wishes of becoming a lawyer, Manet attempts twice, but to no avail, to enrol into Naval School. He boards a training ship in order to travel to Brazil. 1849: Stays in Rio de Janeiro for two years before returning to Paris. 1850: Returns to the School of Fine Arts. He enters the studio of artist Thomas Couture and makes a number of copies of the master works in the Louvre. 1852: His son Léon is born. He does not marry the mother, Suzanne Leenhoff, a piano teacher from Holland, until 1863. -

Manet the Modern Master

Manet the Modern Master ‘Portrait of Mademoiselle Claus’ Edouard Manet (1832-1883) oil on canvas, 111 x 70 cm Painted in 1868, the subject of the portrait is Fanny Claus, a close friend of Manet’s wife Suzanne Leenhoff. It was a preparatory study for ‘Le Balcon’ which now hangs in Musée d’Orsay. Originally the canvas was much larger, but Manet cut it up so that Berthe Morisot appears truncated on the right. He kept the painting in his studio during his lifetime. The artist John Singer Sargent then bought it at the studio sale following the artist’s death in 1884 and brought it to England. It stayed in the family until 2012 when it was put up for sale and The Ashmolean launched a successful fundraising campaign to save the painting from leaving the country. © Ashmolean Museum A modern portrait? Use of family and friends as models Manet’s ‘Portrait of Mlle Claus’ has an Manet broke new ground by defying traditional enigmatic quality that makes it very modern. techniques of representation and by choosing The remote and disengaged look on Fanny’s subjects from the events and circumstances face suggests a sense of isolation in urban of his own time. He also wanted to make society. The painting tells no story and its very a commentary on contemporary life and lack of narrative invites the viewer to construct frequently used family and friends to role play their own interpretations. It is a painting that has everyday (genre) scenes in his paintings. the ability to speak to us across the years. -

The Brothers Le Nain: Painters of 17Th-Century France

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE The Brothers Le Nain: Painters of 17th-Century France West Coast Presentation October 8, 2016–January 29, 2017 | Legion of Honor SAN FRANCISCO—The Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco are pleased to present The Brothers Le Nain: Painters of 17th-Century France, the first major exhibition in the United States devoted to the Le Nain brothers—Antoine (ca. 1598–1648), Louis (ca. 1600/1605–1648) and Mathieu (ca. 1607–1677). The presentation features more than forty of the brothers’ works to highlight the Le Nains’ full artistic production, and is organized in conjunction with the Kimbell Art Museum in Fort Worth, Texas, and the Musée du Louvre-Lens in France. Active in Paris during the 1630s and 1640s, the brothers are today best known for their startlingly realistic depictions of the poor. Painters of altarpieces, portraits and allegories, the brothers’ work was rediscovered in the 19th century by such art historians as Champfleury, and influenced many artists including Gustave Courbet and Édouard Manet. The brothers then became famous as “painters of reality,” admired for their deeply sympathetic and affecting portrayals of hard-working men and women. In these paintings, we see smiling field laborers, city beggars with deadpan expressions, mothers cradling infants with perfect intimacy, and children that dance and play music with a lack of pretension. The Museums’ Peasants before a House is one of the finest examples of this subject. “The brothers Le Nain have not been the subjects of a major exhibition since 1979, when more than 300,000 visitors first came to celebrate their masterful paintings at the Grand Palais in Paris,” says Max Hollein, Director of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco. -

Les Frères Le Nain Et Le Laonnois

- 49 - Les Frères Le Nain et le Laonnois par Pierre LEFÈVRE Ancien bibliothécaire de la ville de Laon Dans ce court aperçu, nous serions heureux de donner quelques précisions utiles concernant la magnifique exposition des œuvres des frères Le Nain, au Grand Palais, à Paris (l),et de répondre à cette question : oui ou non, dans certaines de leurs œuvres, les frères Le Nain se sont-ils inspirés du pays natal (2) ? Nous allons tenter d'y répondre dans l'exposé qui suit. Les premières recherches sur les Le Nain ont été menées par l'écrivain Laonnois Champfleury. Puis trente ans plus tard, il y a eu les importants travaux de Grandin, qui fut plusieurs années conservateur du musée de Laon. Ultérieurement Jamot quitte le Musée de Reims, pour être conservateur au Musée du Louvre. Admirateur convaincu des Le Nain, et aprks de sérieuses, patientes et méritoires recherches, il propose un classement des œuvres, les attribuant à l'aîné Louis, dit << Le Romain >> qu'il considère comme le plus grand peintre, incomparable, de la vie rustique ou à Antoine, dit << Le Jeune >>, ou à Mathieu, dit << Le Chevalier. >> - A l'heure présente, en se fondant sur des recherches radiographi- ques et autres, effectuées en France et à I'étranger, on estime que dans tout tableau il y a plus d'une main. Les très rares indications que l'on relève avec le plus grand soin sont : << LENAIN FECIT >>. Précisons : jamais de prénom. Aussi estime-t-on qu'il s'agit d'œuvres collectives. C'est &idemment une opinion toute différente de celle de Jamot. -

The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art

French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945 The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Editor 4525 Oak Street, Kansas City, Missouri 64111 | nelson-atkins.org Edouard Manet | The Croquet Party, 1871 The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art | French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945 Edouard Manet, The Croquet Party, 1871 Artist Edouard Manet, French, 1832–1883 Title The Croquet Party Object Date 1871 Alternate and Variant The Croquet Party at Boulogne-sur-Mer; La partie de croquet Titles Medium Oil on canvas Dimensions 18 x 28 3/4 in. (45.7 x 73 cm) (Unframed) Signature Signed lower right: Manet Credit Line The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art. Gift of Marion and Henry Bloch, 2015.13.11 doi: 10.37764/78973.5.522 the croquet lawn outside the casino at Boulogne-sur- Catalogue Entry Mer, in northern France. On the far left is Paul Roudier, the artist’s childhood friend and a central member of Manet’s social circle; he is the only figure in the scene to Citation address the spectator directly.1 Alongside him is Jeanne Gonzalès (1852–1924), a talented young painter who Chicago: would enjoy recognition at the Paris Salon from the late 1870s (Fig. 1).2 Jeanne was the younger sister of the Simon Kelly, “Edouard Manet, The Croquet Party, painter Eva (1849–1883), who was Manet’s favorite 1871,” catalogue entry in Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, female pupil. Jeanne, too, received artistic lessons from ed., French Paintings, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Manet and frequented his studio.3 She looks toward Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art (Kansas City: The Léon Leenhoff, Manet’s stepson (and, possibly, his Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021), biological son) and a favorite model for the artist.4 To the https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.522.5407 right is Léon’s mother—Manet’s wife, Suzanne Leenhoff MLA: —who raises her mallet to hit a croquet ball alongside an unknown partner. -

Parola Scenica: Towards Realism in Italian Opera Etdhendrik Johannes Paulus Du Plessis

Parola Scenica: Towards Realism in Italian Opera ETDHendrik Johannes Paulus du Plessis A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Arts, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of PhD by Thesis Abstract This thesis attempts to describe the emergence of a realistic writing style in nine- teenth-century Italian opera of which Giuseppe Verdi was the primary architect. Frequently reinforced by a realistic musico-linguistic device that Verdi would call parola scenica, the object of this realism is a musical syntax in which nei- ther the dramatic intent of the text nor the purely musical intent overwhelms the other. For Verdi the dramatically effective depiction of a ‘slice of a particular life’—a realist theatrical notion—is more important than the mere mimetic description of the words in musical terms—a romantic theatrical notion in line with opera seria. Besides studying the device of parola scenica in Verdi’s work, I also attempt to cast light on its impact on the output of his peers and successors. Likewise, this study investigates how the device, by definition texted, impacts on the orchestra as a means of realist narrative. My work is directed at explaining how these changes in mood of thought were instrumental in effecting the gradual replacement of the bel canto singing style typical of the opera seria of Rossini, Donizetti, and Bellini, by the school of thought of verismo, as exemplified by Verdi’s experiments. Besides the work of Verdi and the early nineteenth-cen- tury Italian operatic Romanticists, I touch also briefly on the œuvres of Puccini, ETDGiordano and the other veristi. -

Les Peintres Du Réel

HISTOIRE DE L’ART Les peintres du réel En réaction à l’académisme des sujets historiques et religieux et aux excès du romantisme, les peintres de la fin du XIXe siècle s’intéressent aux réalités les plus prosaïques. > PAR MARIE-ANGE FOUGÈRE, MAÎTRE DE CONFÉRENCES EN LITTÉRATURE FRANÇAISE, UNIVERSITÉ DE BOURGOGNE ans le dernier tiers du xixe siècle, les impres- quité – lire à ce sujet l’essai d’Erich Auerbach, sionnistes ne sont pas les seuls à rejeter la Mimésis (voir Savoir +) dans lequel l’auteur peinture d’histoire ou la peinture religieuse évoque L’Odyssée d’Homère. Depuis la Renais- et à représenter le réel tel qu’ils le voient et sance, les artistes se sont attachés à représenter la plus selon les canons classiques. Les natu- réalité – le corps humain, le mouvement, la vie ralistes, eux aussi, contestent la peinture quotidienne –, comme l’atteste l’exposition « Les 22 académique. Toutefois, le courant natura- Peintres de la réalité » (musée de l’Orangerie, Dliste a souffert d’un manque de reconnaissance, 1934) qui réunissait des peintres du xviie siècle d’abord parce qu’il ne présente pas une unité stylis- – Charles Le Brun, Simon Vouet, les frères Le Nain, 1031 O tique clairement identifiable, ensuite parce qu’il Philippe de Champaigne, Nicolas Poussin, Lubin TDC N n’apparaît pas sous la forme d’un groupe constitué, Baugin ou encore Georges de La Tour – dont les t enfin parce que son existence fut éclipsée par la fas- œuvres faisaient voisiner scènes paysannes, cination qu’exerça longtemps l’impressionnisme. portraits de gentilshommes et scènes religieuses.