Class 3: the Impressionist Revolution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

16 Exhibition on Screen

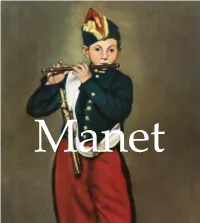

Exhibition on Screen - The Impressionists – And the Man Who Made Them 2015, Run Time 97 minutes An eagerly anticipated exhibition travelling from the Musee d'Orsay Paris to the National Gallery London and on to the Philadelphia Museum of Art is the focus of the most comprehensive film ever made about the Impressionists. The exhibition brings together Impressionist art accumulated by Paul Durand-Ruel, the 19th century Parisian art collector. Degas, Manet, Monet, Pissarro, Renoir, and Sisley, are among the artists that he helped to establish through his galleries in London, New York and Paris. The exhibition, bringing together Durand-Ruel's treasures, is the focus of the film, which also interweaves the story of Impressionism and a look at highlights from Impressionist collections in several prominent American galleries. Paintings: Rosa Bonheur: Ploughing in Nevers, 1849 Constant Troyon: Oxen Ploughing, Morning Effect, 1855 Théodore Rousseau: An Avenue in the Forest of L’Isle-Adam, 1849 (Barbizon School) Jean-François Millet: The Gleaners, 1857 (Barbizon School) Jean-François Millet: The Angelus, c. 1857-1859 (Barbizon School) Charles-François Daubigny: The Grape Harvest in Burgundy, 1863 (Barbizon School) Jean-François Millet: Spring, 1868-1873 (Barbizon School) Jean-Baptiste Camille Corot: Ruins of the Château of Pierrefonds, c. 1830-1835 Théodore Rousseau: View of Mont Blanc, Seen from La Faucille, c. 1863-1867 Eugène Delecroix: Interior of a Dominican Convent in Madrid, 1831 Édouard Manet: Olympia, 1863 Pierre Auguste Renoir: The Swing, 1876 16 Alfred Sisley: Gateway to Argenteuil, 1872 Édouard Manet: Luncheon on the Grass, 1863 Edgar Degas: Ballet Rehearsal on Stage, 1874 Pierre Auguste Renoir: Ball at the Moulin de la Galette, 1876 Pierre Auguste Renoir: Portrait of Mademoiselle Legrand, 1875 Alexandre Cabanel: The Birth of Venus, 1863 Édouard Manet: The Fife Player, 1866 Édouard Manet: The Tragic Actor (Rouvière as Hamlet), 1866 Henri Fantin-Latour: A Studio in the Batingnolles, 1870 Claude Monet: The Thames below Westminster, c. -

Berthe Morisot and Mary Cassatt. Jessica Cresseveur University of Louisville

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 5-2016 The queer child and haut bourgeois domesticity : Berthe Morisot and Mary Cassatt. Jessica Cresseveur University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Part of the American Art and Architecture Commons, Modern Art and Architecture Commons, and the Theory and Criticism Commons Recommended Citation Cresseveur, Jessica, "The queer child and haut bourgeois domesticity : Berthe Morisot and Mary Cassatt." (2016). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 2409. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/2409 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The nivU ersity of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The nivU ersity of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE QUEER CHILD AND HAUT BOURGEOIS DOMESTICITY: BERTHE MORISOT AND MARY CASSATT By Jessica Cresseveur B.A., University of Louisville, 2000 M.A., University College London, 2003 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of the University of Louisville in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Humanities Department of Comparative Humanities University -

L-G-0000349593-0002314995.Pdf

Manet Page 4: Self-Portrait with a Palette, 1879. Oil on canvas, 83 x 67 cm, Mr et Mrs John L. Loeb collection, New York. Designed by: Baseline Co Ltd 127-129A Nguyen Hue, Floor 3, District 1, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam © Sirrocco, London, UK (English version) © Confidential Concepts, worldwide, USA All rights reserved No part of this publication may be reproduced or adapted without the permission of the copyright holder, throughout the world. Unless otherwise specified, copyrights on the works reproduced lies with the respective photographers. Despite intensive research, it has not always been possible to establish copyright ownership. Where this is the case we would appreciate notification ISBN 978-1-78042-029-5 2 “He was greater than we thought he was.” — Edgar Degas 3 Biography 1832: Born Edouard Manet 23 January in Paris, France. His father is Director of the Ministry of Justice. Edouard receives a good education. 1844: Enrols into Rollin College where he meets Antonin Proust who will remain his friend throughout his life. 1848: After having refused to follow his family’s wishes of becoming a lawyer, Manet attempts twice, but to no avail, to enrol into Naval School. He boards a training ship in order to travel to Brazil. 1849: Stays in Rio de Janeiro for two years before returning to Paris. 1850: Returns to the School of Fine Arts. He enters the studio of artist Thomas Couture and makes a number of copies of the master works in the Louvre. 1852: His son Léon is born. He does not marry the mother, Suzanne Leenhoff, a piano teacher from Holland, until 1863. -

Manet the Modern Master

Manet the Modern Master ‘Portrait of Mademoiselle Claus’ Edouard Manet (1832-1883) oil on canvas, 111 x 70 cm Painted in 1868, the subject of the portrait is Fanny Claus, a close friend of Manet’s wife Suzanne Leenhoff. It was a preparatory study for ‘Le Balcon’ which now hangs in Musée d’Orsay. Originally the canvas was much larger, but Manet cut it up so that Berthe Morisot appears truncated on the right. He kept the painting in his studio during his lifetime. The artist John Singer Sargent then bought it at the studio sale following the artist’s death in 1884 and brought it to England. It stayed in the family until 2012 when it was put up for sale and The Ashmolean launched a successful fundraising campaign to save the painting from leaving the country. © Ashmolean Museum A modern portrait? Use of family and friends as models Manet’s ‘Portrait of Mlle Claus’ has an Manet broke new ground by defying traditional enigmatic quality that makes it very modern. techniques of representation and by choosing The remote and disengaged look on Fanny’s subjects from the events and circumstances face suggests a sense of isolation in urban of his own time. He also wanted to make society. The painting tells no story and its very a commentary on contemporary life and lack of narrative invites the viewer to construct frequently used family and friends to role play their own interpretations. It is a painting that has everyday (genre) scenes in his paintings. the ability to speak to us across the years. -

The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art

French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945 The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Editor 4525 Oak Street, Kansas City, Missouri 64111 | nelson-atkins.org Edouard Manet | The Croquet Party, 1871 The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art | French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945 Edouard Manet, The Croquet Party, 1871 Artist Edouard Manet, French, 1832–1883 Title The Croquet Party Object Date 1871 Alternate and Variant The Croquet Party at Boulogne-sur-Mer; La partie de croquet Titles Medium Oil on canvas Dimensions 18 x 28 3/4 in. (45.7 x 73 cm) (Unframed) Signature Signed lower right: Manet Credit Line The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art. Gift of Marion and Henry Bloch, 2015.13.11 doi: 10.37764/78973.5.522 the croquet lawn outside the casino at Boulogne-sur- Catalogue Entry Mer, in northern France. On the far left is Paul Roudier, the artist’s childhood friend and a central member of Manet’s social circle; he is the only figure in the scene to Citation address the spectator directly.1 Alongside him is Jeanne Gonzalès (1852–1924), a talented young painter who Chicago: would enjoy recognition at the Paris Salon from the late 1870s (Fig. 1).2 Jeanne was the younger sister of the Simon Kelly, “Edouard Manet, The Croquet Party, painter Eva (1849–1883), who was Manet’s favorite 1871,” catalogue entry in Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, female pupil. Jeanne, too, received artistic lessons from ed., French Paintings, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Manet and frequented his studio.3 She looks toward Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art (Kansas City: The Léon Leenhoff, Manet’s stepson (and, possibly, his Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021), biological son) and a favorite model for the artist.4 To the https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.522.5407 right is Léon’s mother—Manet’s wife, Suzanne Leenhoff MLA: —who raises her mallet to hit a croquet ball alongside an unknown partner. -

Madame Manet in the Conservatory a Comparison Between Two Versions

MADAME MANET IN THE CONSERVATORY A COMPARISON BETWEEN TWO VERSIONS RESEARCH FORUM PAINTING PAIRS COLLABORATION BY DIANA M. JASKIERNY AND SAMANTHA ROBERTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Our thanks go to the following for their constant and overwhelming support for our research throughout the duration of this project: Aviva Burnstock (Courtauld Institute of Art) Elisabeth Reissner (Courtauld Institute of Art) Karen Serres (Curator, Courtauld Gallery) Maureen Cross (Courtauld Institute of Art) Thierry Ford (Conservator, Nasjonalmuseet for kunst, arkitektur og design, Oslo) Laura Homer (Conservator, Nasjonalmuseet for kunst, arkitektur og design, Oslo) Juliet Wilson Bareau Mary-Anne Stevens Kim Muir (The Art Institute of Chicago) Vivien Green (Curator, Guggenheim, New York) Gillian McMillan (Conservator, Guggenheim, New York) Lois Oliver (Courtauld Institute of Art) The Courtauld Institute of Art 1 Table of Index Page List of Figures 3 I. Introduction 5 II. History 6 Provenance 6 Material placement within the 19th Century 8 III. Composition 11 Technical examination of technique and changes in 11 the composition Changes found in other Manet paintings 15 IV. Materials 18 Pigments and their uses 18 Comparative analysis with a Manet found in the 21 Pushkin The significance of drawings 25 V. Conclusion 28 VI. References 29 2 LIST OF FIGURES Figure 1: Mme Manet in the Conservatory, Édouard Manet, c. 1879, The National Museum of Art, Architecture, and Design Oslo, Norway Figure 2: Mme Manet in the Conservatory, Unknown artist, c. 1875-1895, Private Collection Figure 3: Cross section from privately owned version in regular light showing the presence of one ground layer Figure 4: Cross section from privately owned version in Ultraviolet light showing the presence of one ground layer Figure 5: Scanning X-Ray Fluorescence map - Mercury Figure 6: Scanning X-Ray Fluorescence map - Chrome Figure 7: Series of images illustrating how infrared imaging of the Oslo version can show how the bench posts originally extended to the edge of the canvas. -

Seeing Laure: Race and Modernity from Manet's Olympia to Matisse

Seeing Laure: Race and Modernity from Manet’s Olympia to Matisse, Bearden and Beyond Denise M. Murrell Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2014 © 2013 Denise M. Murrell All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT Seeing Laure: Race and Modernity from Manet’s Olympia to Matisse, Bearden and Beyond Denise M. Murrell During the 1860s in Paris, Edouard Manet and his circle transformed the style and content of art to reflect an emerging modernity in the social, political and economic life of the city. Manet’s Olympia (1863) was foundational to the new manner of painting that captured the changing realities of modern life in Paris. One readily observable development of the period was the emergence of a small but highly visible population of free blacks in the city, just fifteen years after the second and final French abolition of territorial slavery in 1848. The discourse around Olympia has centered almost exclusively on one of the two figures depicted: the eponymous prostitute whose portrayal constitutes a radical revision of conventional images of the courtesan. This dissertation will attempt to provide a sustained art-historical treatment of the second figure, the prostitute’s black maid, posed by a model whose name, as recorded by Manet, was Laure. It will first seek to establish that the maid figure of Olympia, in the context of precedent and Manet’s other images of Laure, can be seen as a focal point of interest, and as a representation of the complex racial dimension of modern life in post-abolition Paris. -

“Manet and Marx: Two Sides of the Coin” by George Heard Hamilton, 1983

Guggenheim Museum Archives Reel-to-Reel collection Hilla Rebay Lecture: “Manet and Marx: Two Sides of the Coin” by George Heard Hamilton, 1983 PART 1 THOMAS M. MESSER And welcome to the fourth Hilla Rebay Lecture at the Guggenheim Museum. As many of you know, Hilla Rebay was the first Director of the Guggenheim Museum, then called the Museum for Non-Objective Painting. And it is Hilla Rebay who is responsible for some of our most important acquisitions, acquisitions that we continue to be proud of, and that show up in such exhibitions as the present survey of Kandinsky’s art during the Russian years, and the Bauhaus. A foundation in her name was created still during her lifetime, and occupies itself with that part of the collection that [00:01:00] remains in the possession of the executors of Hilla’s will, but is administered, actually, and is in custody at the Guggenheim Museum. So the foundation works closely with us, with relation to the collection, as well as toward such activities as the lecture series. The annual Hilla Rebay lectures, then, have enabled us during the years to bring to the Guggenheim very distinguished lecturers, especially in twentieth century art, none of whom more so than George Heard Hamilton, Director Emeritus of the Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute in Williamstown. Dr. Hamilton is known to [00:02:00] many of us as the author of such decisive and important publications as the 19th and 20th Century Art: Painting, Sculpture, and Architecture, and, even more apropos to the lecture tonight, his book on Manet and his critics. -

The Influence of Japonisme in Claude Monet's Impression

THE INFLUENCE OF JAPONISME IN CLAUDE MONET’S IMPRESSION, SUNRISE A thesis submitted to the College of Arts of Kent State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts by Chelsea N. Cooper May 2020 Thesis written by Chelsea Cooper B.A., Kent State University, 2016 M.A., Kent State University, 2020 Approved by _________________________________________ Shana Klein, Ph.D., Advisor _________________________________________ Marie Bukowski, M.F.A., Director, School of Art _________________________________________ John R Crawford-Spinelli, Ed.D., Dean, College of Arts ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF FIGURES………………………………………………………….........…….…….iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS……………………………………………………….........………vi CHAPTER I. THE PIONEERING CLAUDE MONET 1 Introduction………………………………………………………………..........……..1 Monet’s Life and Career Leading to Impression, Sunrise.............................................2 Before the Birth of Impression, Sunrise…………………………………....…............5 II. ENDING SECLUSION- JAPANESE IMPORTING 10 History of the Trade………………………………………………………........…….10 Japonisme: A Cultural Exploitation……………..…………………………........…...12 The Great Masters: Hiroshige, Hokusai, and Utamaro……………………........…....14 Monet’s Obsession with Japonisme…………………………………………........….17 The Prevalent Influence of Ukiyo-e on Nineteenth Century Artists…………............21 III. IMPRESSION, SUNRISE: A PAINTING FIT FOR WOODBLOCK 27 The Beginnings of Impressionism...............................................................................27 A -

Manet's Contemporaries

MANET’S ‘COUP DE TÊTE’: THE SECRETS HIDDEN IN PLAIN SIGHT O COUP DE TÊTE DE MANET: OS SEGREDOS ’: The Secrets Hidden in Plain Sight ESCONDIDOS EM PLENA LUZ DO DIA Coup de Tête Manet’s ‘ Manet’s Moyra Anne Ashford EL COUP DE TÊTE DE MANET: LOS SECRETOS ESCONDIDOS A MOYRA ANNE ASHFORD PLENA LUZ DEL DÍA ARS - N 40 ANO 18 126 ABSTRACT Modern art began with Édouard Manet’s The Picnic (Le Déjeuner sur L’Herbe, 1863). A small minority of scholars have ventured that Manet’s impetus for breaking from Artigo Inédito Moyra Anne Ashford* tradition stemmed from memories of his 1849 voyage to Brazil. This view is eschewed by the majority and the museum establishment, who hold to a French and classical origin. * Essayist and former journalist at The Sunday Through a close examination of early written sources, the paintings themselves and Times and The Daily Telegraph, United links to 19th century Rio, the author proposes that Manet worked distinct Rio memories Kingdom. DOI: 10.11606/issn.2178- into two pivotal paintings: The Picnic, which he set in the forests of Guanabara Bay; 0447.ars.2020.176216 Olympia (1863) was inspired not by a Parisian brothel, but by slave-owning, mid- nineteenth century Rio de Janeiro. This article recounts how the research unfolded. KEYWORDS Édouard Manet; Rio de Janeiro; Émile Zola; Olympia; Impressionism ’: The Secrets Hidden in Plain Sight RESUMO RESUMEN A arte moderna teve início com Le Déjeuner sur L’Herbe (1863), El arte moderno empezó con Le Déjeuner sur L’Herbe de Édouard Manet. -

A Short History of Celebrity This Page Intentionally Left Blank

A Short History of Celebrity This page intentionally left blank To view this page, please refer to the print version of this book. Copyright © 2010 by Princeton University Press Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540 In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TW All Rights Reserved Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Inglis, Fred. A short history of celebrity / Fred Inglis. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-691-13562-5 (hardcover : alk. paper) 1. Celebrities—History. 2. Celebrities—Biography. 3. Fame— Social aspects—History. 4. Fame—Psychological aspects— History. 5. History, Modern. 6. Popular culture—History. 7. Civilization, Modern. I. Title. D210.I525 2010 305.5’2—dc22 2009050143 British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available This book has been composed in Adobe Garamond and ITC Golden Cockeral Printed on acid-free paper. ∞ press.princeton.edu Printed in the United States of America 1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2 For Jessie and Abby Guardians of the Middle Station This page intentionally left blank Contents Acknowledgements ix part i Fame and Feeling 1. The Performance of Celebrity 3 2. A Very Short History of the Feelings 19 part ii The Rise of Celebrity: A Three-Part Invention 3. The London–Brighton Road, 1760–1820 37 4. Paris: Haute Couture and the Painting of Modern Life 74 5. New York and Chicago: Robber Barons and the Gossip Column, 1880–1910 108 part iii The Past in the Present 6. The Geography of Recognition: Celebrity on Its Holidays 135 7. -

Painting at the Origin

1 Painting at the Origin Paul Galvez The title of the Getty exhibition Courbet and the Modern Landscape puts my problem front and center: how can we call a work such as the Getty Museum’s Grotto of Sarrazine (ca. 1864, fig. 1) modern when, in the same decade, other works such as Éduoard Manet’s Races at Longchamp (1867[?], fig. 2) are proposing the breathtaking pace of the spectacle and the brushstroke as the defining features of modern painting? Or to put it another way, does it make any sense to mention in the same breath the brooding, figureless grottoes of 1864 and the multicolored swarm of humanity gathering for Music in the Tuileries Garden (1862, fig. 3)? My answer is, of course, yes, we can. But to do so means finding a place for darkness and deceleration in our understanding of modern experience, at the expense of—or, rather, as an alternative to—the brilliance and immediacy made familiar to us by the art of Manet and the Impressionists. In the first part of this paper, I discuss two pictorial strategies Gustave Courbet uses in 1864 to create the feeling of slow immersion. I will then reemerge from the depths of Courbet’s painting, so to speak, to explore its modernity from another point of view, not that of speed and the city, but that of matter and its origins. Figure 1 Gustave Courbet (French, 1819–1877). The Grotto of Sarrazine near Nans-sous-Sainte-Anne, ca. 1864. Oil on canvas, 50 x 60 cm (19 11/16 x 23 5/8 in.).