Crossyborder Intelligibility ± on the Intelligibility of Low

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

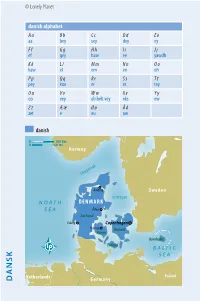

Danish Alphabet DENMARK Danish © Lonely Planet

© Lonely Planet danish alphabet A a B b C c D d E e aa bey sey dey ey F f G g H h I i J j ef gey haw ee yawdh K k L l M m N n O o kaw el em en oh P p Q q R r S s T t pey koo er es tey U u V v W w X x Y y oo vey do·belt vey eks ew Z z Æ æ Ø ø Å å zet e eu aw danish 0 100 km 0 60 mi Norway Skagerrak Aalborg Sweden Kattegat NORTH DENMARK SEA Århus Jutland Esberg Copenhagen Odense Zealand Funen Bornholm Lolland BALTIC SEA Poland Netherlands Germany DANSK DANSK DANISH dansk introduction What do the fairy tales of Hans Christian Andersen and the existentialist philosophy of Søren Kierkegaard have in common (apart from pondering the complexities of life and human character)? Danish (dansk dansk), of course – the language of the oldest European monarchy. Danish contributed to the English of today as a result of the Vi- king conquests of the British Isles in the form of numerous personal and place names, as well as many basic words. As a member of the Scandinavian or North Germanic language family, Danish is closely related to Swedish and Norwegian. It’s particularly close to one of the two official written forms of Norwegian, Bokmål – Danish was the ruling language in Norway between the 15th and 19th centuries, and was the base of this modern Norwegian literary language. In pronunciation, however, Danish differs considerably from both of its neighbours thanks to its softened consonants and often ‘swallowed’ sounds. -

Department of Regional Health Research Faculty of Health Sciences - University of Southern Denmark

Department of Regional Health Research Faculty of Health Sciences - University of Southern Denmark The focus of Department of Regional Health Research, Region of Southern Denmark, and Region Zealand is on cooperating to create the best possible conditions for research and education. 1 Successful research environments with open doors With just 11 years of history, Department of Regional Health Research (IRS) is a relatively “The research in IRS is aimed at the treatment new yet, already unconditional success of the person as a whole and at the more experiencing growth in number of employees, publications and co-operations across hospitals, common diseases” professional groups, institutions and national borders. University partner for regional innovations. IRS is based on accomplished hospitals professionals all working towards improving The research in IRS is directed towards the man’s health and creating value for patients, person as a whole and towards the more citizens and the community by means of synergy common diseases. IRS reaches out beyond the and high professional and ethical standards. traditional approach to research and focusses on We largely focus on the good working the interdisciplinary and intersectoral approach. environment, equal rights and job satisfaction IRS makes up the university partner and among our employees. We make sure constantly organisational frame for clinical research and to support the delicate balance between clinical education at hospitals in Region of Southern work, research and teaching. Denmark* and Region Zealand**. Supports research and education Many land registers – great IRS continues working towards strengthening geographical spread research and education and towards bringing the There is a great geographical spread between the department and the researchers closer together hospitals, but research environments and in the future. -

Hele Rapporten I Pdf Format

Miljø- og Energiministeriet Danmarks Miljøundersøgelser Typeinddeling og kvalitetselementer for marine områder i Danmark Vandrammedirektiv–projekt, Fase 1 Faglig rapport fra DMU, nr. 369 [Tom side] Miljø- og Energiministeriet Danmarks Miljøundersøgelser Typeinddeling og kvalitetselementer for marine områder i Danmark Vandrammedirektiv–projekt, Fase 1 Faglig rapport fra DMU, nr. 369 2001 Kurt Nielsen Afdeling for Sø- og Fjordøkologi Bent Sømod Aarhus Amt Trine Christiansen Afdeling for Havmiljø Datablad Titel: Typeinddeling og kvalitetselementer for marine områder i Danmark Undertitel: Vandrammedirektiv-projekt, Fase 1 Forfattere: Kurt Nielsen1, Bent Sømod2, Trine Christiansen3 Afdelinger: 1Afd. for Sø- og Fjordøkologi 2Aarhus Amt 3Afd. for Havmiljø Serietitel og nummer: Faglig rapport fra DMU nr. 369 Udgiver: Miljø- og Energiministeriet Danmarks Miljøundersøgelser URL: http://www.dmu.dk Udgivelsestidspunkt: August 2001 Faglig kommentering: Dorte Krause-Jensen, Danmarks Miljøundersøgelser; Henning Karup, Miljøstyrelsen; Nanna Rask, Fyns Amt Layout: Pia Nygård Christensen Korrektur: Aase Dyhl Hansen og Pia Nygård Christensen Bedes citeret: Nielsen, K., Sømod, B. & T. Christiansen 2001: Typeinddeling og kvalitetselementer for marine områder i Danmark. Vandrammedirektiv-projekt, Fase 1. Danmarks Miljøundersøgelser. 107 s. - Faglig rapport fra DMU nr. 369. http://faglige-rapporter.dmu.dk. Gengivelse tilladt med tydelig kildeangivelse. Sammenfatning: Rapporten indeholder en opdeling af de danske kystområder i 16 forskellige typer i henhold -

Scheepvaart Ten Oosten Van De Ijssel Deel 4: Vechtezompen Op De Overijsselse Vecht

Scheepvaart ten oosten van de IJssel deel 4: Vechtezompen op de Overijsselse Vecht Het oosten van het land heeft zijn varenstraditie ontdekt. Er verschenen al veel nieuwe zompen op het water, daarover schreven we in de vorige afleveringen van deze serie. De nieuwste plannen betreffen twee Vechtzompen die gaan varen op de Overijsselse Vecht. Uiteraard niet meer met vracht maar met toeristen. Tekst en foto's Wim de Bruijn e.a. In het westen van Overijssel werd vroeger ook wel van een dubbelzomp. In de punt van De eerste Vechtezomp kreeg ook een zeiltuig. Het oor- nooit gesproken over zompen, maar over de pegzomp was een vooronder met helemaal spronkelijke tuig maakte gebruik van twee sprieten Vechtezompen, naar de rivier waarop ze voe- voorin een klein kacheltje of fornuisje. Men ren. Toch werden ze altijd in Enter gebouwd, sliep op een bank van planken tegen het ach- de schipper met één lijn het grootzeil tegen de net als de zompen. Men kende er twee soor- terschot van het vooronder. Ze voerden het mast trekken, zodat het geen wind meer ving. ten: lösse zompen met losse boeisels, ook wel grote spriettuig met twee sprieten in een vier- pegzompen genoemd en opgeboeide zompen kant grootzeil. Er kon snel zeil worden gemin- De Overijsselse Vecht met een berghout. Dat woord peg is afgeleid derd door er één spriet uit te halen en de top De Overijsselse Vecht is een regenwaterrivier van het peghöltien, een 25 cm lang houtje, iets te laten vallen. Die werd dan met een lijntje met een oorsprong in Münsterland in Duits- gebogen en aangescherpt als een mesje. -

Possessive Constructions in Modern Low Saxon

POSSESSIVE CONSTRUCTIONS IN MODERN LOW SAXON a thesis submitted to the department of linguistics of stanford university in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of master of arts Jan Strunk June 2004 °c Copyright by Jan Strunk 2004 All Rights Reserved ii I certify that I have read this thesis and that, in my opinion, it is fully adequate in scope and quality as a thesis for the degree of Master of Arts. Joan Bresnan (Principal Adviser) I certify that I have read this thesis and that, in my opinion, it is fully adequate in scope and quality as a thesis for the degree of Master of Arts. Tom Wasow I certify that I have read this thesis and that, in my opinion, it is fully adequate in scope and quality as a thesis for the degree of Master of Arts. Dan Jurafsky iii iv Abstract This thesis is a study of nominal possessive constructions in modern Low Saxon, a West Germanic language which is closely related to Dutch, Frisian, and German. After identifying the possessive constructions in current use in modern Low Saxon, I give a formal syntactic analysis of the four most common possessive constructions within the framework of Lexical Functional Grammar in the ¯rst part of this thesis. The four constructions that I will analyze in detail include a pronominal possessive construction with a possessive pronoun used as a determiner of the head noun, another prenominal construction that resembles the English s-possessive, a linker construction in which a possessive pronoun occurs as a possessive marker in between a prenominal possessor phrase and the head noun, and a postnominal construction that involves the preposition van/von/vun and is largely parallel to the English of -possessive. -

Funen Energy Plan

STRATEGIC ENERGY PLANNING AT MUNICIPAL LEVEL Funen Energy Plan Funen is characterised by a high share of agriculture, From a systemic point of view, he emphasizes that the with remarkable biomass resources, and well- energy system needs to be redesigned. He finds it developed district heating and gas distributing important to link large heat pumps to surplus heat systems. To ensure the success and stability of future from industries so that they will be as cost-effective as local investments in the energy sector, Funen has possible. Furthermore, he stresses the importance of developed a political framework for the future energy using heat pumps to harness production of electricity investments, an energy plan. from wind turbines. The plan was developed in a wide cooperation between 9 municipalities on Funen and Ærø, 5 supply companies, University of Southern Denmark (SDU), Centrovice (the local agricultural trade organisation), and Udvikling Fyn (a regional business development company). In total, 36 students from SDU have made their Christian Tønnesen, Project manager and Head of the diploma work under the auspices of the energy plan Settlement & Business Department, Faaborg-Midtfyn thus creating a win-win satiation for students, Municipality, underlines: “The ambition for Funen university, local businesses, and municipalities. Energy Plan is to create a platform for the energy Exporting biomass fuel instead of electricity stakeholders, so that they from a common point of view can approach a joint planning for the future The energy plan presents a number of energy with a focus on innovation and optimal recommendations linked to particularly challenging solutions.” energy areas, where robust and long-term navigation Students contributing to real life energy plans is crucial. -

Coalitieakkoord Dinkelland Duurzaam Doorontwikkelen

Coalitieakkoord 2018 – 2022: Dinkelland Duurzaam Doorontwikkelen Dinkelland Duurzaam Doorontwikkelen Uitnodigend, pragmatisch en respectvol Voor u ligt het coalitieakkoord 2018-2022 dat gesloten is door de fracties van het CDA en de VVD. Met dit akkoord zetten beide partijen de samenwerking voort die ze in 2017 zijn aangegaan. CDA en VVD hebben uitgesproken er vertrouwen in te hebben Dinkelland de komende vier jaren samen goed te kunnen besturen. In dit akkoord geven wij onze ambities weer, waarbij de Strategische Agenda van de Raad het vertrekpunt is. De Strategische Agenda en onze ambities hebben we uitgewerkt in verschillende agenda’s. Met deze agenda’s geven we ruimte voor de inbreng van inwoners, organi- saties, bedrijven en de gemeenteraad om samen de goede dingen te doen voor Dinkelland. Ondertekend op dinsdag 15 mei 2018 CDA VVD Jos Jogems Marcel Tijink Coalitieakkoord 2018 – 2022: Dinkelland Duurzaam Doorontwikkelen 2 Inhoud Strategische Agenda van de Raad Voorwoord Dinkelland Duurzaam Doorontwikkelen Inleiding In deze kaders vindt u terug wat er in de strategische agenda van de Raad op dit onderwerp staat. Agenda Aantrekkelijk wonen en leven Agenda Duurzaamheid Agenda Beleving Agenda Dinkelland onderneem’t Agenda Inclusieve samenleving Agenda Sport en bewegen Speerpunten andere partijen Agenda Leven lang leren Agenda Veiligheid, toezicht en handhaving Samen Duurzaam Doorontwikkelen Agenda Dinkelland in de Regio Op 20 april jongstleden heeft elke fractie van de gemeenteraad op enkele thema’s een inhoudelijke bijdra- Dinkelland financieel ge kunnen leveren voor het coalitieakkoord. De coalitie- partners geven in dit kader aan hoe zij met deze inbreng Portefeuilleverdeling omgaan. Coalitieakkoord 2018 – 2022: Dinkelland Duurzaam Doorontwikkelen 3 Inleiding Dinkelland is volop in ontwikkeling. -

Modeling Regional Variation in Voice Onset Time of Jutlandic Varieties of Danish

Chapter 4 Modeling regional variation in voice onset time of Jutlandic varieties of Danish Rasmus Puggaard Universiteit Leiden It is a well-known overt feature of the Northern Jutlandic variety of Danish that /t/ is pronounced with short voice onset time and no affrication. This is not lim- ited to Northern Jutland, but shows up across the peninsula. This paper expands on this research, using a large corpus to show that complex geographical pat- terns of variation in voice onset time is found in all fortis stops, but not in lenis stops. Modeling the data using generalized additive mixed modeling both allows us to explore these geographical patterns in detail, as well as test a number of hypotheses about how a number of environmental and social factors affect voice onset time. Keywords: Danish, Jutlandic, phonetics, microvariation, regional variation, stop realization, voice onset time, aspiration, generalized additive mixed modeling 1. Introduction A well-known feature of northern Jutlandic varieties of Danish is the use of a variant of /t/ known colloquially as the ‘dry t’. While the Standard Danish variant of /t/ has a highly affricated release, the ‘dry t’ does not. Puggaard (2018) showed that variation in this respect goes beyond just that particular phonetic feature and dialect area: the ‘dry t’ also has shorter voice onset time (VOT) than affricated variants, and a less affricated, shorter variant of /t/ is also found in the center of Jutland. This paper expands on Puggaard (2018) with the primary goals of providing a sounder basis for investigating the geographic spread of the variation, and to test whether the observed variation is limited to /t/ or reflects general patterns in plosive realization. -

CEMENT for BUILDING with AMBITION Aalborg Portland A/S Portland Aalborg Cover Photo: the Great Belt Bridge, Denmark

CEMENT FOR BUILDING WITH AMBITION Aalborg Portland A/S Cover photo: The Great Belt Bridge, Denmark. AALBORG Aalborg Portland Holding is owned by the Cementir Group, an inter- national supplier of cement and concrete. The Cementir Group’s PORTLAND head office is placed in Rome and the Group is listed on the Italian ONE OF THE LARGEST Stock Exchange in Milan. CEMENT PRODUCERS IN Cementir's global organization is THE NORDIC REGION divided into geographical regions, and Aalborg Portland A/S is included in the Nordic & Baltic region covering Aalborg Portland A/S has been a central pillar of the Northern Europe. business community in Denmark – and particularly North Jutland – for more than 125 years, with www.cementirholding.it major importance for employment, exports and development of industrial knowhow. Aalborg Portland is one of the largest producers of grey cement in the Nordic region and the world’s leading manufacturer of white cement. The company is at the forefront of energy-efficient production of high-quality cement at the plant in Aalborg. In addition to the factory in Aalborg, Aalborg Portland includes five sales subsidiaries in Iceland, Poland, France, Belgium and Russia. Aalborg Portland is part of Aalborg Portland Holding, which is the parent company of a number of cement and concrete companies in i.a. the Nordic countries, Belgium, USA, Turkey, Egypt, Malaysia and China. Additionally, the Group has acti vities within extraction and sales of aggregates (granite and gravel) and recycling of waste products. Read more on www.aalborgportlandholding.com, www.aalborgportland.dk and www.aalborgwhite.com. Data in this brochure is based on figures from 2017, unless otherwise stated. -

Overijsselaars Gezocht

Overijsselaars gezocht Inhoud 1. Overijsselaars gezocht ............................................................................. 7 Inleiding ................................................................................................................................... 7 Vormen van onderzoek ............................................................................................................ 8 Vastleggen van gegevens .......................................................................................................... 9 Is er al onderzoek gedaan? ..................................................................................................... 10 Genealogie en internet ........................................................................................................... 12 Archiefbewaarplaatsen in Overijssel ....................................................................................... 13 Archiefbezoek: hoe gaat dat? ................................................................................................. 15 Literatuur ............................................................................................................................... 16 Online verwijzingen ................................................................................................................ 16 2. Het begin van het archiefonderzoek ...................................................... 17 Inleiding ................................................................................................................................ -

CUH Was Seemg More Tourist Traffic Than Usual. Harlingen Is a on The

The Frisians in 'Beowulf' Bremmer Jr., Rolf H.; Conde Silvestre J.C, Vázquez Gonzáles N. Citation Bremmer Jr., R. H. (2004). The Frisians in 'Beowulf'. In V. G. N. Conde Silvestre J.C (Ed.), Medieval English Literary and Cultural Studies (pp. 3-31). Murcia: SELIM. doi:•Lei fgw 1020 Version: Not Applicable (or Unknown) License: Leiden University Non-exclusive license Downloaded from: https://hdl.handle.net/1887/20833 Note: To cite this publication please use the final published version (if applicable). THE FRISIANS IN BEOWULF- BEOWULF IN FRISIA: THE VICISSITUDES TIME ABSTRACT One of the remarkable aspects is that the scene of the main plot is set, not in but in Scandinavia. Equa!l)' remarkable is that the Frisian~ are the only West Germanic tribe to a considerable role in tvvo o{the epic's sub-plots: the Finnsburg Episode raid on Frisia. In this article, I willjirst discuss the significance of the Frisians in the North Sea area in early medieval times (trade), why they appear in Beowul{ (to add prestige), and what significance their presence may have on dating (the decline ajter 800) The of the article deals with the reception of the editio princeps of Beovvulf 1 881) in Frisia in ha!fofth!:' ninete?nth century. summer 1 1, winding between Iiarlingen and HU.<~CUH was seemg more tourist traffic than usual. Harlingen is a on the coast the province of Friesland/Fryslan, 1 \Vijnaldum an insignificant hamlet not far north from Harlingen. Surely, the tourists have enjoyed the sight of lush pastures leisurely grazed Friesian cattle whose fame dates back to Roman times. -

Old Frisian, an Introduction To

An Introduction to Old Frisian An Introduction to Old Frisian History, Grammar, Reader, Glossary Rolf H. Bremmer, Jr. University of Leiden John Benjamins Publishing Company Amsterdam / Philadelphia TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of 8 American National Standard for Information Sciences — Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Bremmer, Rolf H. (Rolf Hendrik), 1950- An introduction to Old Frisian : history, grammar, reader, glossary / Rolf H. Bremmer, Jr. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. 1. Frisian language--To 1500--Grammar. 2. Frisian language--To 1500--History. 3. Frisian language--To 1550--Texts. I. Title. PF1421.B74 2009 439’.2--dc22 2008045390 isbn 978 90 272 3255 7 (Hb; alk. paper) isbn 978 90 272 3256 4 (Pb; alk. paper) © 2009 – John Benjamins B.V. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, by print, photoprint, microfilm, or any other means, without written permission from the publisher. John Benjamins Publishing Co. · P.O. Box 36224 · 1020 me Amsterdam · The Netherlands John Benjamins North America · P.O. Box 27519 · Philadelphia pa 19118-0519 · usa Table of contents Preface ix chapter i History: The when, where and what of Old Frisian 1 The Frisians. A short history (§§1–8); Texts and manuscripts (§§9–14); Language (§§15–18); The scope of Old Frisian studies (§§19–21) chapter ii Phonology: The sounds of Old Frisian 21 A. Introductory remarks (§§22–27): Spelling and pronunciation (§§22–23); Axioms and method (§§24–25); West Germanic vowel inventory (§26); A common West Germanic sound-change: gemination (§27) B.