Identity in Ideologically Driven Organizing: Narrative Construction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Al Qaeda Network a New Framework for Defining the Enemy

THE AL QAEDA NETWORK A NEW FRAMEWORK FOR DEFINING THE ENEMY KATHERINE ZIMMERMAN SEPTEMBER 2013 THE AL QAEDA NETWORK A NEW FRAMEWORK FOR DEFINING THE ENEMY KATHERINE ZIMMERMAN SEPTEMBER 2013 A REPORT BY AEI’S CRITICAL THREATS PROJECT ABOUT US About the Author Katherine Zimmerman is a senior analyst and the al Qaeda and Associated Movements Team Lead for the Ameri- can Enterprise Institute’s Critical Threats Project. Her work has focused on al Qaeda’s affiliates in the Gulf of Aden region and associated movements in western and northern Africa. She specializes in the Yemen-based group, al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula, and al Qaeda’s affiliate in Somalia, al Shabaab. Zimmerman has testified in front of Congress and briefed Members and congressional staff, as well as members of the defense community. She has written analyses of U.S. national security interests related to the threat from the al Qaeda network for the Weekly Standard, National Review Online, and the Huffington Post, among others. Acknowledgments The ideas presented in this paper have been developed and refined over the course of many conversations with the research teams at the Institute for the Study of War and the American Enterprise Institute’s Critical Threats Project. The valuable insights and understandings of regional groups provided by these teams directly contributed to the final product, and I am very grateful to them for sharing their expertise with me. I would also like to express my deep gratitude to Dr. Kimberly Kagan and Jessica Lewis for dedicating their time to helping refine my intellectual under- standing of networks and to Danielle Pletka, whose full support and effort helped shape the final product. -

Congressional Record—Senate S1674

S1674 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — SENATE March 12, 2013 will have a ripple effect that could curb REMEMBERING BORAH VAN always gone first, providing a blueprint medical discoveries and weaken the DORMOLEN that helped guide negotiations on Cap- economies across the country. Mr. CORNYN. Mr. President, I want itol Hill, but not under this President. Dr. Francis Collins, Director of the to start my remarks today by remem- The budget process is an opportunity NIH, says there is no question that se- bering a great Texan who passed away for the President to outline his prior- questration will slow the development just yesterday. Sandy, my wife, and I ities. It is an opportunity for the Presi- of an influenza vaccine and cancer re- are deeply saddened by the loss of dent to tell the American people what search. we can afford and how we are going to Eli Zerhouni, head of NIH under Borah Van Dormolen, a remarkable pa- triot, a respected leader, and a loving pay for it. Above all, it is an oppor- President George W. Bush, said: tunity for the President to show real We are going to maim our innovation capa- wife. Borah rose through the ranks of the leadership on issues of national impor- bilities if we do these abrupt deep cuts at tance. NIH. It will impact science for generations U.S. Army, achieving the rank of lieu- to come. tenant colonel. After more than two As ADM Mike Mullen, the former Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, Right now, when so much good re- decades serving her Nation in the uni- said: The greatest national security search is moving us forward, we should form of the U.S. -

The Second Circuit As Arbiter of National Security Law

Fordham Law Review Volume 85 Issue 1 Article 8 2016 Threats Against America: The Second Circuit as Arbiter of National Security Law David Raskin U.S. Attorney in the Western District of Missouri Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/flr Part of the National Security Law Commons Recommended Citation David Raskin, Threats Against America: The Second Circuit as Arbiter of National Security Law, 85 Fordham L. Rev. 183 (2016). Available at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/flr/vol85/iss1/8 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. It has been accepted for inclusion in Fordham Law Review by an authorized editor of FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THREATS AGAINST AMERICA: THE SECOND CIRCUIT AS ARBITER OF NATIONAL SECURITY LAW David Raskin* INTRODUCTION For nearly 100 years, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit has been a leading force in defining and resolving the uniquely thorny issues that arise at the intersection of individual liberty and national security. The court’s decisions in this arena are characterized by its willingness to tackle difficult questions and its skill in balancing the needs of the government with the rights of the accused to ensure fundamental fairness in the ages of espionage and terror. I. THE ESPIONAGE PROBLEM AND THE RISE OF THE COLD WAR STATE In 1917, soon after the United States entered World War I, Congress passed the Espionage Act.1 The new law strengthened existing prohibitions on actions harmful to the national defense and, most notably, authorized the death penalty for anyone convicted of sharing information with the intent to harm U.S. -

Trends in Terrorism Threats to the United States and the Future of the Terrorism Risk Insurance Act

CENTER FOR TERRORISM RISK MANAGEMENT POLICY CHILD POLICY This PDF document was made available CIVIL JUSTICE from www.rand.org as a public service of EDUCATION the RAND Corporation. ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENT HEALTH AND HEALTH CARE Jump down to document6 INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS NATIONAL SECURITY The RAND Corporation is a nonprofit POPULATION AND AGING research organization providing PUBLIC SAFETY SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY objective analysis and effective SUBSTANCE ABUSE solutions that address the challenges TERRORISM AND facing the public and private sectors HOMELAND SECURITY TRANSPORTATION AND around the world. INFRASTRUCTURE Support RAND Purchase this document Browse Books & Publications Make a charitable contribution For More Information Visit RAND at www.rand.org Explore RAND Center for Terrorism Risk Management Policy View document details Limited Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law as indicated in a notice appearing later in this work. This electronic representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for non- commercial use only. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of our research documents. This product is part of the RAND Corporation monograph series. RAND monographs present major research findings that address the challenges facing the public and private sectors. All RAND mono- graphs undergo rigorous peer review to ensure high standards for research quality and objectivity. Trends in Terrorism Threats to the United States and the Future of the Terrorism Risk Insurance Act Peter Chalk, Bruce Hoffman, Robert Reville, Anna-Britt Kasupski The research described in this report was conducted by the RAND Center for Terrorism Risk Management Policy. -

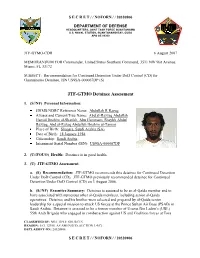

Detainee Is an Admitted Al-Qaida Facilitator, Who Had the Full Trust and Confidence of Al-Qaida Leadership

SECRET // DEPARTMENT OF DEFENSE STATES COMMAND HEADQUARTERS , JOINT TASK FORCE GUANTANAMO U.S. NAVAL STATION , GUANTANAMO BAY , CUBA APOAE09360 CUBA JTF- GTMO- CDR 26 May2008 MEMORANDUMFORCommander, UnitedStates SouthernCommand, 3511NW 91st Avenue, Miami, FL 33172 SUBJECT Recommendation for Continued Detention Under DoD Control (CD) for Guantanamo Detainee, ISN - 001461DP (S ) JTF - GTMO Detainee Assessment 1. ( S) Personal Information : JDIMS/ NDRC ReferenceName Mohammed Ahmad Rabbani Current/ True Name andAliases: AhmedGhulam Rabbani, Abu Badr Abu Rahman alPakistani, MuhammedHusayn Shah, Farida, Baderal-Madany, Sir Tum Place of Birth: SaudiArabia (SA ) Date ofBirth: 1970 Citizenship: Pakistan (PK ) InternmentSerial Number (ISN) US9PK -001461DP 2. ( U //FOUO Health: Detainee is in overall good health. 3. (U ) JTF-GTMOAssessment: a. (S ) Recommendation : JTF-GTMO recommends this detainee for Continued Detention Under DoD Control (CD) . JTF-GTMO previously recommended detainee for Continued Detention Under DoD Control (CD) on 21 September 2007. b. (S ) Executive Summary: Detainee is an admitted al-Qaida facilitator, who had the full trust and confidence of al-Qaida leadership . Detainee admitted working directly for senior al-Qaida operational planner Khalid Shaykh Muhammad, aka (KSM), 010024DP (KU- 10024). Detainee provided support to multiple al-Qaida sponsored terrorist operations and plans throughout the greater Middle East and possibly the US while maintaining several safe houses inPakistan (PK). Detainee received basic and advanced CLASSIFIED BY : MULTIPLE SOURCES REASON : 12958, AS AMENDED , SECTION 1.4( C ) DECLASSIFY ON : 20330526 SECRET NOFORN 20330526 SECRET // 20330526 JTF - GTMO -CDR SUBJECT : Recommendation for Continued Detention Under Control (CD) for Guantanamo Detainee , ISN -001461DP (S ) trainingat al-Qaida associatedtrainingcamps. ADDITIONALINFORMATIONABOUT THIS DETAINEEISAVAILABLEINAN SCISUPPLEMENT. -

Abu Ghaith Recalls 9/11 with Laden Inside Cave

SUBSCRIPTION THURSDAY, MARCH 20, 2014 JAMADA ALAWWAL 19, 1435 AH www.kuwaittimes.net Islamic scholar Teenager, UK hopes to Van Persie defends army officers foil fraudsters rescues United Brotherhood killed in Egypt with new in Champions in Kuwait3 violence8 1-pound25 coin League20 Abu Ghaith recalls 9/11 Max 27º Min 16º with Laden inside cave High Tide 11:03 & 21:33 Low Tide Ex-Qaeda spokesman unexpectedly testifies at US trial 04:46 & 16:05 40 PAGES NO: 16110 150 FILS NEW YORK: In surprise testimony in a Manhattan court- room yesterday, Osama bin Laden’s son-in-law recount- Trial closure ed the night of the Sept 11 attacks, when the Al-Qaeda leader sent a messenger to drive him into a mountain- of key roads ous area for a meeting inside a cave in Afghanistan. “Did you learn what happened? We are the ones who did it,” before summit the son-in-law, Sulaiman Abu Ghaith, recalled bin Laden telling him. When bin Laden asked what he thought KUWAIT: As the convening of the Arab summit next would happen next, Abu Ghaith testified that he week requires security and traffic measures, the traf- responded by predicting America “will not settle until it fic department will close some roads starting kills you and topples the state of the Taleban”. Saturday, March 22 at 8:45 am on a trial basis to reg- Bin Laden responded: “You’re being too pes- ulate traffic flows during the arrival of participating simistic,” Abu Ghaith recalled. Bin Laden then told the delegations. -

Combating Al Qaeda and the Militant Islamic Threat

TESTIMONY THE ARTS This PDF document was made available from www.rand.org as a public CHILD POLICY service of the RAND Corporation. CIVIL JUSTICE EDUCATION Jump down to document ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENT 6 HEALTH AND HEALTH CARE INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS The RAND Corporation is a nonprofit research NATIONAL SECURITY POPULATION AND AGING organization providing objective analysis and effective PUBLIC SAFETY solutions that address the challenges facing the public SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY and private sectors around the world. SUBSTANCE ABUSE TERRORISM AND HOMELAND SECURITY TRANSPORTATION AND INFRASTRUCTURE Support RAND WORKFORCE AND WORKPLACE Browse Books & Publications Make a charitable contribution For More Information Visit RAND at www.rand.org Explore RAND Testimony View document details Limited Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law as indicated in a notice appearing later in this work. This electronic representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for non- commercial use only. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of our research documents for commercial use. TESTIMONY Combating Al Qaeda and the Militant Islamic Threat BRUCE HOFFMAN CT-255 February 2006 Testimony presented to the House Armed Services Committee, Subcommittee on Terrorism, Unconventional Threats and Capabilities on February 16, 2006 This product is part of the RAND Corporation testimony series. RAND testimonies record testimony presented by RAND associates to federal, state, or local legislative committees; government-appointed commissions and panels; and private review and oversight bodies. The RAND Corporation is a nonprofit research organization providing objective analysis and effective solutions that address the challenges facing the public and private sectors around the world. -

Terrorism and the Mass Media After Al Qaeda: a Change of Course?

Terrorism and the Mass Media after Al Qaeda: A Change of Course? Manuel R. Torres Soriano Athena Intelligence Journal Vol. 3, No 2 Artículo 1 1 de abril de 2008 www.athenaintelligence.org ISSN 1998-5237 Athena Intelligence Journal Vol. 3, No 1, (2008), pp. 1-20 Terrorism and the Mass Media after Al Qaeda: A Change of Course? Manuel R. Torres Soriano Resumen Abstract Este artículo analiza las posibles relaciones This article analyzes the possible relationship entre grupos terroristas y medios de between terrorist groups and the media. As an comunicación. Se utiliza como estudio de caso a example, a case study on the Al Qaeda la organización Al Qaeda, analizándose su organization will be used. Our methodology will discurso público y su evolución histórica. Su involve analyzing the content of its public percepción de los mass media , es el resultado de statements and examining the developments un cálculo de oportunidad, lo que determina that have taken place during its history as an tres fases históricas: 1) De hostilidad hacia unos organization. Both perspectives suggest that medios a los cuales responsabiliza de que su terrorism’s view of the media, far from being mensaje sea ocultado o distorsionado; 2) composed of rigorous ideological or political Adaptación a un nuevo entorno, donde principles, is shaped by their calculations of existen canales dispuestos a interpretar la estimated opportunities. Its perception of the realidad desde una perspectiva mucho más mass media, has depended on its perception of cercana a la ideología yihadista (principalmente estimated media impact. This has determined Al Jazeera ); 3) Explotación de internet como three stages during its history: 1) Hostility estrategia indirecta de acercamiento a los toward media that it has held responsible for medios de masas. -

Download the PDF File

S E C R E T / / NOFORN / / 20320806 DEPARTMENT OF DEFENSE HEADQUARTERS, JOINT TASK FORCE GUANTANAMO U.S. NAVAL STATION, GUANTANAMO BAY, CUBA APO AE 09360 JTF-GTMO-CDR 6 August 2007 MEMORANDUM FOR Commander, United States Southern Command, 3511 NW 9lst Avenue, Miami, FL 33172 SUBJECT: Recommendation for Continued Detention Under DoD Control (CD) for Guantanamo Detainee, ISN US9SA-000067DP (S) JTF-GTMO Detainee Assessment 1. (S//NF) Personal Information: JDIMS/NDRC Reference Name: Abdullah R Razaq Aliases and Current/True Name: Abd al-Razzaq Abdallah Hamid Ibrahim al-Sharikh, Abu Hammam, Shaykh Abdul Razzaq, Abd al-Razaq Abdallah Ibrahim al-Tamini Place of Birth: Shaqara, Saudi Arabia (SA) Date of Birth: 18 January 1984 Citizenship: Saudi Arabia Internment Serial Number (ISN): US9SA-000067DP 2. (U//FOUO) Health: Detainee is in good health. 3. (U) JTF-GTMO Assessment: a. (S) Recommendation: JTF-GTMO recommends this detainee for Continued Detention Under DoD Control (CD). JTF-GTMO previously recommended detainee for Continued Detention Under DoD Control (CD) on 3 August 2006. b. (S//NF) Executive Summary: Detainee is assessed to be an al-Qaida member and to have associated with numerous other al-Qaida members, including senior al-Qaida operatives. Detainee and his brother were selected and prepared by al-Qaida senior leadership for a special mission to attack US forces at the Prince Sultan Air Base (PSAB) in Saudi Arabia. Detainee is assessed to be a former member of Usama Bin Laden’s (UBL) 55th Arab Brigade who engaged in combat action against US and Coalition forces at Tora CLASSIFIED BY: MULTIPLE SOURCES REASON: E.O. -

Jf

From: [~~~~~~~fI(( ~~~~]USAMA) </O=USA/OU=M A/CN=RECIPIEN TS/CN~ b6, b7C ··-·-·-·-·-·-·-·-·-·-·-·-·-·- i• Sent: Saturday, March 22, 2014 5:29 PM ,.----- ------ --·--- - To: ["-·---b6;-·b7C·---·-·:(USAMA)!- ·-·-·bECi)1c·-·-·-~usa.doj go_y?.:;i b6, b 7-_~_juSAMA) ':----------lisa:ao·. ov>i_______ _ b6 , b7C ,(USAMA)! b6 , b7C alusa.do·. ov>· :-_l?_~!_l?Jf·bic- ·--.}-~-rusAMX)°<;b6 b 'TC___- '@usa .do{go-~;;; r~ ·bs~·-bll- ·-](usAMA) r·-·-6,C6tc·-·-·~-iisi.aoj. gov > r -·-·-·-·bif i/ic·-·-·-·-·-·:0sAMA) r-·-·-bs:·-i:;1c··-·-·-4i"ii"s"a~doj. gov >; •·-·-·-·-·-·-·-·-·-·-·-·-·-·7.-·•·•·-·-·•·•·-·.. 1·-·-• - · - · - ·r-..:r-.:n.u·.:l"'..:r-.:!"'..:r-.:1"'..:r-.:!"'..:r-.:l"'.i • (... ....... • • • ., ••••••• • p : b6 b7C :(USAMA)! b6 b7C @usa.d0J gov>; Fn -·- .;ti;1c·~------(USAMA) \-·-·1>·1i",-·&1c-·t:gTiisa:aoTi(6v>; ;-·--·-·-·~s.-bf€~-~~~[USAMAV--ti~~~C:~:'.:~:llii~~d.ru=·-·o~>; ("""":'""i;e:"b=;-c·-·-·-·-·-·-·[UsAMA)C~~~~~J7-r~~~J?9usa .doj .g'o-,;;:·1 b6, b7C kUSAMA) r~..-b6, ij"fc;'"'-·lyiisa~dofgov > '-·-·---·-·-·--·-·---·-·---·-' 1--·-·-·-·-·-·-·-·-·-·-·-·-.I Subject : FW: The INVESTIGATIVE PROJECT on Terrori sm Update: 21 March 2014 From: The Investigative Project [mailto:update @ctnews .org] Sent: Friday,M arch 21, 2014 5:08 PM To: I b6, b7C (USAMA) Sub.iea:·1fie"IN'vtSTIGATIVE PROJECT on TerrorismUpda te: 21 March2 014 The Update 21 March 2014 [email protected] General security, policy 1. Iranian ship, in plain view but shrouded in mystery, looks very familiar to US 2. Al Qaeda urges followers to bomb world targets with instructions on how to make a car bomb 3. Chinese police university trains Beijing hackers 4. Pentagon goes hypersonic with long-range rapid attack weapon 5. -

May 21, 2020 Sent Via Facsimile & E-Mail Hon. Mitch Mcconnell

May 21, 2020 Sent via Facsimile & E-Mail Hon. Mitch McConnell Majority Leader U.S. Senate S-230, The Capitol Washington, DC 20515 Hon. Nancy Pelosi Speaker U.S. House of Representatives Rayburn House Office Building Washington, DC 20515 Re: Converting Guantánamo Bay Military Commissions Into An Article III Court Dear Majority Leader McConnell and Speaker Pelosi: The U.S. Military Commissions in Guantánamo Bay, Cuba were created to provide legal proceedings for “enemy combatant” detainees. Their purpose was to bring perpetrators to swift justice within the bounds of due process and provide closure to the victims’ families. However, the Military Commissions have fallen far short of these goals. The proceedings are slow, ineffective, and lacking in transparency. Pre-trial proceedings alone are approaching two decades without resolution and half of the convictions by Military Commission have been reversed on appeal. Prosecuting detainees in Military Commission proceedings means accepting that victims’ families may never see cases resolved, that defendants will not receive a speedy trial, and that Guantánamo will have another excuse to remain open despite overwhelming justification for its closure. In stark contrast, Article III courts have delivered fast, fair, and effective justice to nearly 700 terrorism cases since 9/11. The solution to this problem is typically framed as binary: either permit detainees to come to the United States to be tried before Article III courts or continue to hear their cases in Military Commission proceedings. Indeed, the New York City Bar Association has advocated for Guantánamo detainees to be tried before federal courts in the United States. -

Download the Transcript

BIN LADEN-2017/06/05 1 THE BROOKINGS INSTITUTION FALK AUDITORIUM THE EXILE: THE STUNNING INSIDE STORY OF OSAMA BIN LADEN AND AL QAEDA IN FLIGHT Washington, D.C. Monday, June 5, 2017 PARTICIPANTS: Moderator: BRUCE RIEDEL Senior Fellow and Director, Intelligence Project The Brookings Institution Featured Speaker: CATHERINE SCOTT-CLARK Author and Investigative Journalist * * * * * ANDERSON COURT REPORTING 706 Duke Street, Suite 100 Alexandria, VA 22314 Phone (703) 519-7180 Fax (703) 519-7190 BIN LADEN-2017/06/05 2 P R O C E E D I N G S MR. RIEDEL: Well, good morning, ladies and gentlemen. Welcome to The Brookings Institution and welcome to another in our series of events of the Brookings Intelligence project. It is a great pleasure for me this morning to spend an hour and a half with you and with Cathy Scott-Clark, co- author of what I think is one of the most important books that will come out this year, “The Exile”. I’ll explain why I think that in just a minute. I want to begin by asking you to please mute your cell phones, so we don’t have competition as to who has the best cell phone. I’d also ask you to bear with the program. We’re going to proceed in the following manner: I will have a conversation with Cathy for about 45 minutes or so, until about 9:45, and then we will open it up to questions from you. When we go to questions from the audience, could you please identify yourself and your affiliation just so we know the background to the questioner.