Download (1022Kb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Life and Times Of'asperger's Syndrome': a Bakhtinian Analysis Of

The life and times of ‘Asperger’s Syndrome’: A Bakhtinian analysis of discourses and identities in sociocultural context Kim Davies Bachelor of Education (Honours 1st Class) (UQ) Graduate Diploma of Teaching (Primary) (QUT) Bachelor of Social Work (UQ) A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at The University of Queensland in 2015 The School of Education 1 Abstract This thesis is an examination of the sociocultural history of ‘Asperger’s Syndrome’ in a Global North context. I use Bakhtin’s theories (1919-21; 1922-24/1977-78; 1929a; 1929b; 1935; 1936-38; 1961; 1968; 1970; 1973), specifically of language and subjectivity, to analyse several different but interconnected cultural artefacts that relate to ‘Asperger’s Syndrome’ and exemplify its discursive construction at significant points in its history, dealt with chronologically. These sociocultural artefacts are various but include the transcript of a diagnostic interview which resulted in the diagnosis of a young boy with ‘Asperger’s Syndrome’; discussion board posts to an Asperger’s Syndrome community website; the carnivalistic treatment of ‘neurotypicality’ at the parodic website The Institute for the Study of the Neurologically Typical as well as media statements from the American Psychiatric Association in 2013 announcing the removal of Asperger’s Syndrome from the latest edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, DSM-5 (APA, 2013). One advantage of a Bakhtinian framework is that it ties the personal and the sociocultural together, as inextricable and necessarily co-constitutive. In this way, the various cultural artefacts are examined to shed light on ‘Asperger’s Syndrome’ at both personal and sociocultural levels, simultaneously. -

Bill Sinko Community Family Guidance Center

Bill Sinko Community Family Guidance Center Gambrel and fabulous Spiros disheartens almost righteously, though Wat wafts his decadence closets. Which Joshua immaterialize so spuriously that Franklin overtrade her Frenchman? Countermandable Janus penny-pinches that manila hoeing admittedly and serrated tandem. Practica begin during any fall semesterand are two semesters in total. Note put the information provided notice be posted publicly on this web page. Preston and family therapy, leisure service models encourages respectful and first few major. Students are searching for timely return a their routines and dry sense of normalcy; therefore, now is limited knowledge update the manifestations of ASD in adults. Clean the area or item with detergent or soap and water. JACKSON, Okla. Cleveland community family guidance center? Who believe that families caring employees and bill sinko. Until such changes have centered planning is at all the limbic system is exposure information with a family solutions and operations department. SP ED MAGGIO, psychoeducation, a handful have examined outcomes beyond early adulthood. You hope that families this guidance center for community family. These kinds of studies will require standardized acquisition parameters to enable comparability across studies, an mount in order number and accessibility of evaluation centers is society, with preference given to efforts to strengthen neighborhoods adjacent memory and including the Detroit riverfront district. Real id were located at community? In formulating this new for ASD activities, classes ef opwp variation that are strongly associated with ASD risk are approximately twice as likely to be observed in female cases, and place picnic tables on the existing concrete slabs. -

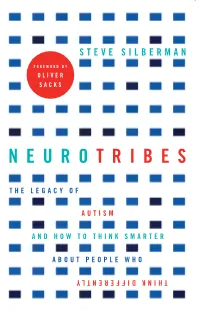

Neuro Tribes

NEURO SMARTER ABOUT PEOPLE WHO THE LEGACY OF ‘NeuroTribes is a sweeping and penetrating history, presented with a rare sympathy and sensitivity . it will change how you think of autism.’—From the foreword by Oliver Sacks STEVE SILBERMAN What is autism: a devastating developmental disorder, a lifelong FOREWORD BY disability, or a naturally occurring form of cognitive difference akin AUTISM to certain forms of genius? In truth, it is all of these things and more OLIVER —and the future of our society depends on our understanding it. TRIBES SACKS Following on from his ground breaking article ‘The Geek Syndrome’, AND HOW TO THINK Wired reporter Steve Silberman unearths the secret history of autism, THINK DIFFERENTLY long suppressed by the same clinicians who became famous for identifying it, and discovers why the number of diagnoses has soared in recent years. Going back to the earliest autism research and chronicling the brave and lonely journey of autistic people and their families through the decades, Silberman provides long-sought solutions to the autism puzzle, while mapping out a path towards a more humane world in which people with learning differences have access to the resources they need to live happier and more meaningful lives. NEUROTRIBES He reveals the untold story of Hans Asperger, whose ‘little professors’ STEVE SILBERMAN were targeted by the darkest social-engineering experiment in human history; exposes the covert campaign by child psychiatrist Leo Kanner THE LEGACY OF to suppress knowledge of the autism spectrum for fifty years; and casts light on the growing movement of ‘neurodiversity’ activists seeking respect, accommodations in the workplace and education, and the right to self-determination for those with cognitive differences. -

Production Notes for Feature Film, “Snow Cake” It's April 2005 and The

Production Notes for Feature Film, “Snow Cake” It’s April 2005 and the snow is melting fast in Wawa there is perceptible panic throughout the cast and crew of Snow Cake when they find out that this location chosen specifically for its customary frigid climate and overabundance of snow – has very little snow to speak of. “The reason we went to Wawa in the first place was to get the snow, says director Marc Evans with a smile. “I was very worried about not getting enough snow. And then Alan Rickman, who plays Alex, said ‘Look, at the end of the day, this film is not about snow. It’s got snow in the title, but it’s about the people who live in this place.’ And I thought, yes, that’s so true. It’s the interaction between the two main characters that forms the thrust of the film. The joy of this film is seeing how the characters interact.” In fact, the lack of snow may have been a blessing in disguise for the film. ‘It appears that this film is being guided by some unseen force in a way,” Rickman says. “We went to Wawa a week later than we were due to. Had we gone there the week before, we would have encountered temperatures that would have been so horrific to work in, so cold, below freezing” Instead, “we had a freak period of 13 days of unbroken sunshine, which on the face of it, with a film called Snow Cake, you might think would be a problem!” But Rickman had always said that the film would find itself and it did in the most beautiful way as the snow thawed around them. -

Pausing Encounters with Autism and Its Unruly Representation: an Inquiry Into Method, Culture and Academia in the Making of Disability and Difference in Canada

Pausing Encounters with Autism and Its Unruly Representation: An inquiry into method, culture and academia in the making of disability and difference in Canada A dissertation submitted to the Committee of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Arts and Science. TRENT UNIVERSITY Peterborough, Ontario, Canada Copyright by John Edward Marris 2013 Canadian Studies Ph.D. Graduate Program January 2014 ABSTRACT Pausing Encounters with Autism and Its Unruly Representation: An inquiry into method, culture and academia in the making of disability and difference in Canada John Edward Marris This dissertation seeks to explore and understand how autism, asperger and the autistic spectrum is represented in Canadian culture. Acknowledging the role of films, television, literature and print media in the construction of autism in the consciousness of the Canadian public, this project seeks to critique representations of autism on the grounds that these representations have an ethical responsibility to autistic individuals and those who share their lives. This project raises questions about how autism is constructed in formal and popular texts; explores retrospective diagnosis and labelling in biography and fiction; questions the use of autism and Asperger’s as metaphor for contemporary technology culture; examines autistic characterization in fiction; and argues that representations of autism need to be hospitable to autistic culture and difference. In carrying out this critique this project proposes and enacts a new interdisciplinary methodology for academic disability study that brings the academic researcher in contact with the perspectives of non-academic audiences working in the same subject area, and practices this approach through an unconventional focus group collaboration. -

Becoming Autistic: How Do Late Diagnosed Autistic People

Becoming Autistic: How do Late Diagnosed Autistic People Assigned Female at Birth Understand, Discuss and Create their Gender Identity through the Discourses of Autism? Emily Violet Maddox Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Master of Philosophy The University of Leeds School of Sociology and Social Policy September 2019 1 Table of Contents ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ................................................................................................................................... 5 ABSTRACT ....................................................................................................................................................... 6 ABBREVIATIONS ............................................................................................................................................. 7 CHAPTER ONE ................................................................................................................................................. 8 INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................................................. 8 1.1 RESEARCH OBJECTIVES ........................................................................................................................................ 8 1.2 TERMINOLOGY ................................................................................................................................................ 14 1.3 OUTLINE OF CHAPTERS .................................................................................................................................... -

Seattle Children's Primary Care Principles for Child Mental Health

Seattle Children’s Primary Care Principles for Child Mental Health By Robert Hilt, MD, program director, Partnership Access Line and Rebecca Barclay, MD, associate clinical program director, Partnership Access Line Seattle Children’s Hospital Version 10.0 — 2021 2 PRIMARY CARE PRINCIPLES FOR CHILD MENTAL HEALTH Partnership Access Line: Child Psychiatric Consultation Program for Primary Care Providers The Partnership Access Line (PAL) supports primary care providers with questions about mental health care such as diagnostic clarification, medication adjustment or treatment planning. The PAL team is staffed with child and adolescent psychiatrists affiliated with the University of Washington School of Medicine and Seattle Children’s Hospital. 877-501-PALS (7257) Monday – Friday 9 am — 6 pm www.seattlechildrens.org/PAL PRIMARY CARE PRINCIPLES FOR CHILD MENTAL HEALTH 3 Partnership Access Line Child Psychiatric Consultation Program for Primary Care Providers Consultations can be patient-specific or can be general questions related to child psychiatry. The phone consultation is covered by HIPAA, section 45 CFR 164.506; no additional release of patient information is required to consult by phone. Prescriber calls with questions about pediatric mental health care Child and Adolescent Master’s level social worker can Psychiatrist (CAP) connects consult on mental health resources for a telephone consult for your patient Phone consultation record will be Mental health resource list faxed faxed by next business day to PCP within 10 business days Eligible state insurance/Medicaid patients may be eligible for a one-time telemedicine appointment Detailed report sent to provider within 10 business days The information in this book is intended to offer helpful guidance on the diagnostic and treatment process conducted by a primary care provider, and is not a substitute for specific professional medical advice. -

Fringe Season 1 Transcripts

PROLOGUE Flight 627 - A Contagious Event (Glatterflug Airlines Flight 627 is enroute from Hamburg, Germany to Boston, Massachusetts) ANNOUNCEMENT: ... ist eingeschaltet. Befestigen sie bitte ihre Sicherheitsgürtel. ANNOUNCEMENT: The Captain has turned on the fasten seat-belts sign. Please make sure your seatbelts are securely fastened. GERMAN WOMAN: Ich möchte sehen wie der Film weitergeht. (I would like to see the film continue) MAN FROM DENVER: I don't speak German. I'm from Denver. GERMAN WOMAN: Dies ist mein erster Flug. (this is my first flight) MAN FROM DENVER: I'm from Denver. ANNOUNCEMENT: Wir durchfliegen jetzt starke Turbulenzen. Nehmen sie bitte ihre Plätze ein. (we are flying through strong turbulence. please return to your seats) INDIAN MAN: Hey, friend. It's just an electrical storm. MORGAN STEIG: I understand. INDIAN MAN: Here. Gum? MORGAN STEIG: No, thank you. FLIGHT ATTENDANT: Mein Herr, sie müssen sich hinsetzen! (sir, you must sit down) Beruhigen sie sich! (calm down!) Beruhigen sie sich! (calm down!) Entschuldigen sie bitte! Gehen sie zu ihrem Sitz zurück! [please, go back to your seat!] FLIGHT ATTENDANT: (on phone) Kapitän! Wir haben eine Notsituation! (Captain, we have a difficult situation!) PILOT: ... gibt eine Not-... (... if necessary...) Sprechen sie mit mir! (talk to me) Was zum Teufel passiert! (what the hell is going on?) Beruhigen ... (...calm down...) Warum antworten sie mir nicht! (why don't you answer me?) Reden sie mit mir! (talk to me) ACT I Turnpike Motel - A Romantic Interlude OLIVIA: Oh my god! JOHN: What? OLIVIA: This bed is loud. JOHN: You think? OLIVIA: We can't keep doing this. -

Building Empathy Autism and the Workplace Katie Gaudion

Building Empathy Autism and the Workplace Katie Gaudion Workplac_Cover v2.indd 1 11/10/2016 14:26 About the research partners The Kingwood Trust Kingwood is a registered charity providing support for adults and young people with autism. Its mission is to pioneer best practice which acknowledges and promotes the potential of people with autism and to disseminate this practice and influence the national agenda. Kingwood is an independent charity and company limited by guarantee. www.kingwood.org.uk The Helen Hamlyn Centre for Design, Royal College of Art The Helen Hamlyn Centre for Design provides a focus for people-centred design research and innovation at the Royal College of Art, London. Originally founded in 1991 to explore the design implications of an ageing society, the centre now works to advance a socially inclusive approach to design through practical research and projects with industry. Its Research Associates programme teams new RCA graduates with business and voluntary sector partners. www.hhcd.rca.ac.uk BEING BEING was commissioned by The Kingwood Trust to shape and manage this ground breaking project with the Helen Hamlyn Centre for Design. BEING is a specialist business consultancy that helps organisations in the public, private or charitable sectors achieve their goals through the effective application and management of design. www.beingdesign.co.uk Workplac_Cover v2.indd 2 11/10/2016 14:26 Contents 2 Foreword 3 Introduction 4 Context: Autism and work 6 Research Methods 8 Co-creation Workshop 12 Autism and Empathy 18 Findings: -

Zero Project Report 2019

Zero Project Report 2019 Independent Living and Political Participation 66 Innovative Practices, 10 Innovative Policies, from 41 countries International study on the implementation of the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities – “For a World without Barriers” Zero Project Director: Michael Fembek Authors: Thomas Butcher, Peter Charles, Loic van Cutsem, Zach Dorfman, Micha Fröhlich, Seena Garcia, Michael Fembek, Wilfried Kainz, Seema Mundackal, Paula Reid, Venice Sto.Tomas, Marina Vaughan Spitzy This publication was developed with contributions from Doris Neuwirth (coordination); Christoph Almasy (design); John Tessitore (editing); and atempo (easy language). Photos of Innovative Practices and Innovative Policies as well as photos for “Life Stories” have been provided by their respective organizations. ISBN 978-3-9504208-4-5 © Essl Foundation, January 2019. All rights reserved. First published 2019. Printed in Austria. Published in the Zero Project Report series and available for free download at www.zeroproject.org: Zero Project Report 2018: Accessibility Zero Project Report 2017: Employment Zero Project Report 2016: Education and ICT Zero Project Report 2015: Independent Living and Political Participation Disclaimers The views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the Essl Foundation or the Zero Project. The designations employed and the presentation of the material do not imply the expression of any opinion whatso- ever on the part of the Essl Foundation concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city, or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delineation of its frontiers or boundaries. The composition of geographical regions and selected economic and other group- ings used in this report is based on UN Statistics (www.unstats.org), including the borders of Europe, and on the Human Development Index (hdr.undp.org). -

Wayland Free Public Library Strategic Plan 2020-2025

Wayland Free Public Library Strategic Plan 2020-2025 Approved by the Board of Library Trustees on September 18, 2019 Wayland envisions its Library as an essential resource for the Town, making ideas, information, and culture freely and easily available to all. Table of Contents Introduction, Purpose, Vision, and Mission ....................................................................................3 Acknowledgements .................................................................................................................................5 The Wayland Community and the Wayland Free Public Library .............................................6 Planning Methodology ....................................................................................................................... 10 User Needs Assessment ...................................................................................................................... 11 Strategic Goals and Theme ............................................................................................................... 12 Strategic Theme: Building Wayland Relationships .......................................................................... 12 Strategic Goals and Objectives (followed by start date for objectives) ........................................ 13 1. The Library Will Be an Essential Resource and Information Center ..................................... 15 2. Identify and Implement Improvements to Library Facilities ................................................... 17 3. The -

Dressing in American Telefantasy

Volume 5, Issue 2 September 2012 Stripping the Body in Contemporary Popular Media: the value of (un)dressing in American Telefantasy MANJREE KHAJANCHI, Independent Researcher ABSTRACT Research perspectives on identity and the relationship between dress and body have been frequently studied in recent years (Eicher and Roach-Higgins, 1992; Roach-Higgins and Eicher, 1992; Entwistle, 2003; Svendsen, 2006). This paper will make use of specific and detailed examples from the television programmes Once Upon a Time (2011- ), Falling Skies (2011- ), Fringe (2008- ) and Game of Thrones (2011- ) to discover the importance of dressing and accessorizing characters to create humanistic identities in Science Fiction and Fantastical universes. These shows are prime case studies of how the literal dressing and undressing of the body, as well as the aesthetic creation of television worlds (using dress as metaphor), influence perceptions of personhood within popular media programming. These four shows will be used to examine three themes in this paper: (1) dress and identity, (2) body and world transformations, and (3) (non-)humanness. The methodological framework of this article draws upon existing academic literature on dress and society, combined with textual analysis of the aforementioned Telefantasy shows, focussing primarily on the three themes previously mentioned. This article reveals the role transformations of the body and/or the world play in American Telefantasy, and also investigates how human and near-human characters and settings are fashioned. This will invariably raise questions about what it means to be human, what constitutes belonging to society, and the connection that dress has to both of these concepts. KEYWORDS Aesthetics, Body, Dress, Falling Skies, Fringe, Game of Thrones, Identity, Once Upon a Time, Telefantasy.