Production Notes for Feature Film, “Snow Cake” It's April 2005 and The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pausing Encounters with Autism and Its Unruly Representation: an Inquiry Into Method, Culture and Academia in the Making of Disability and Difference in Canada

Pausing Encounters with Autism and Its Unruly Representation: An inquiry into method, culture and academia in the making of disability and difference in Canada A dissertation submitted to the Committee of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Arts and Science. TRENT UNIVERSITY Peterborough, Ontario, Canada Copyright by John Edward Marris 2013 Canadian Studies Ph.D. Graduate Program January 2014 ABSTRACT Pausing Encounters with Autism and Its Unruly Representation: An inquiry into method, culture and academia in the making of disability and difference in Canada John Edward Marris This dissertation seeks to explore and understand how autism, asperger and the autistic spectrum is represented in Canadian culture. Acknowledging the role of films, television, literature and print media in the construction of autism in the consciousness of the Canadian public, this project seeks to critique representations of autism on the grounds that these representations have an ethical responsibility to autistic individuals and those who share their lives. This project raises questions about how autism is constructed in formal and popular texts; explores retrospective diagnosis and labelling in biography and fiction; questions the use of autism and Asperger’s as metaphor for contemporary technology culture; examines autistic characterization in fiction; and argues that representations of autism need to be hospitable to autistic culture and difference. In carrying out this critique this project proposes and enacts a new interdisciplinary methodology for academic disability study that brings the academic researcher in contact with the perspectives of non-academic audiences working in the same subject area, and practices this approach through an unconventional focus group collaboration. -

Disability in an Age of Environmental Risk by Sarah Gibbons a Thesis

Disablement, Diversity, Deviation: Disability in an Age of Environmental Risk by Sarah Gibbons A thesis presented to the University of Waterloo in fulfillment of the thesis requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English Waterloo, Ontario, Canada, 2016 © Sarah Gibbons 2016 I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this thesis. This is a true copy of the thesis, including any required final revisions, as accepted by my examiners. I understand that my thesis may be made electronically available to the public. ii Abstract This dissertation brings disability studies and postcolonial studies into dialogue with discourse surrounding risk in the environmental humanities. The central question that it investigates is how critics can reframe and reinterpret existing threat registers to accept and celebrate disability and embodied difference without passively accepting the social policies that produce disabling conditions. It examines the literary and rhetorical strategies of contemporary cultural works that one, promote a disability politics that aims for greater recognition of how our environmental surroundings affect human health and ability, but also two, put forward a disability politics that objects to devaluing disabled bodies by stigmatizing them as unnatural. Some of the major works under discussion in this dissertation include Marie Clements’s Burning Vision (2003), Indra Sinha’s Animal’s People (2007), Gerardine Wurzburg’s Wretches & Jabberers (2010) and Corinne Duyvis’s On the Edge of Gone (2016). The first section of this dissertation focuses on disability, illness, industry, and environmental health to consider how critics can discuss disability and environmental health in conjunction without returning to a medical model in which the term ‘disability’ often designates how closely bodies visibly conform or deviate from definitions of the normal body. -

The Joy of Autism: Part 2

However, even autistic individuals who are profoundly disabled eventually gain the ability to communicate effectively, and to learn, and to reason about their behaviour and about effective ways to exercise control over their environment, their unique individual aspects of autism that go beyond the physiology of autism and the source of the profound intrinsic disabilities will come to light. These aspects of autism involve how they think, how they feel, how they express their sensory preferences and aesthetic sensibilities, and how they experience the world around them. Those aspects of individuality must be accorded the same degree of respect and the same validity of meaning as they would be in a non autistic individual rather than be written off, as they all too often are, as the meaningless products of a monolithically bad affliction." Based on these extremes -- the disabling factors and atypical individuality, Phil says, they are more so disabling because society devalues the atypical aspects and fails to accommodate the disabling ones. That my friends, is what we are working towards -- a place where the group we seek to "help," we listen to. We do not get offended when we are corrected by the group. We are the parents. We have a duty to listen because one day, our children may be the same people correcting others tomorrow. In closing, about assumptions, I post the article written by Ann MacDonald a few days ago in the Seattle Post Intelligencer: By ANNE MCDONALD GUEST COLUMNIST Three years ago, a 6-year-old Seattle girl called Ashley, who had severe disabilities, was, at her parents' request, given a medical treatment called "growth attenuation" to prevent her growing. -

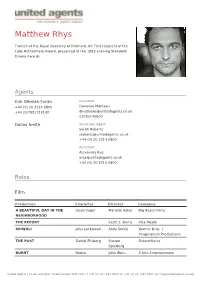

Matthew Rhys

Matthew Rhys Trained at the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art First recipient of the Lady Rothermere Award, presented at the 1993 Evening Standard Drama Awards Agents Kirk Whelan-Foran Assistant +44 (0) 20 3214 0800 Donovan Mathews +44 (0)7920713142 [email protected] 02032140800 Dallas Smith Associate Agent Sarah Roberts [email protected] +44 (0) 20 3214 0800 Assistant Alexandra Rae [email protected] +44 (0) 20 3214 0800 Roles Film Production Character Director Company A BEAUTIFUL DAY IN THE Lloyd Vogel Marielle Heller Big Beach Films NEIGHBORHOOD THE REPORT Scott Z. Burns Vice Media MOWGLI John Lockwood Andy Serkis Warner Bros. | Imaginarium Productions THE POST Daniel Ellsberg Steven DreamWorks Spielberg BURNT Reece John Wells 3 Arts Entertainment United Agents | 12-26 Lexington Street London W1F OLE | T +44 (0) 20 3214 0800 | F +44 (0) 20 3214 0801 | E [email protected] Production Character Director Company THE SCAPEGOAT John Charles Island Pictures Sturridge LUSTER Joseph Miller ADAM MASON Azurelight Pictures PATAGONIA Mateo Marc Evans Rainy Day Films ABDUCTION CLUB Strang Steven Schwartz Pathe DEATHWATCH Doc M.J. Bassett Pathe FAKERS Nick Blake Richard Janes Faking It Productions COME WHAT MAY Percy Christian Carion Nord-Ouest Productions GUILTY PLEASURES Count David Leland Boccaccio Productions Dzerzhinsky HEART Sean Charles Granada McDougal HOUSE OF AMERICA Boyo Marc Evans September Films LOVE AND OTHER DISASTERS Peter Simon Alek Keshishian Skyline Ltd PAVAROTTI IN DAD'S ROOM Nob Sara Sugarman Dragon -

14 Jan 2011 Draft

MOVING BEYOND LOVE AND LUCK: BUILDING RIGHT RELATIONSHIPS AND RESPECTING LIVED EXPERIENCE IN NEW ZEALAND AUTISM POLICY by HILARY STACE A thesis submitted to the Victoria University of Wellington in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Victoria University of Wellington 2011 Abstract Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) diagnoses have been rising rapidly in recent years and New Zealand is just one country grappling with the policy challenges this presents. Currently, love, such as a supportive family, and luck, that appropriate services are available, are required by people with autism and their families for good outcomes, a situation that is neither equitable nor sustainable. Autism was first named as a separate condition in 1943. The concept of autism has developed significantly since then in many ways, including as the cultural identity that many autistic adults now claim. Influenced by the international disability rights movement and local activism, New Zealand policy is now based on the social model of disability, whereby society as a whole has responsibility for removing disabling barriers. In 1997, a New Zealand mother, unable to find appropriate support at a time of crisis, killed her autistic daughter. A decade of policy work followed, leading to the 2008 publication of the New Zealand Autism Spectrum Disorder Guideline (Ministries of Health and Education, 2008) which is the first whole-of-spectrum, whole-of-life, whole- of-government, best practice approach in the world to address the extensive issues surrounding ASD. Prioritisation and initial attempts at implementation revealed new problems. The complexity, lack of simple solutions and fragmentation of autism policy indicates that this is a „wicked‟ policy problem. -

Patagonian Road Movies and Migration from Wales

I D E N T I D A D E S Núm. 5, Año 3 Diciembre 2013 pp. 131-136 ISSN 2250-5369 Patagonian road movies and migration from Wales Esther Whitfield1 Abstract This paper analyzes two recent films, Patagonia (2011) and Separado! (2010), both produced in Wales and set in Patagonia. It proposes that both take advantage of the codes and tropes of the road movie genre, and of the history of Welsh emigration to Patagonia, to situate Welsh language and culture in both a local and global context. Key Words Wales - Patagonia - road movie - emigration. Las road movies patagónicas y la migración desde Gales Resumen Este trabajo analiza dos películas recients, Patagonia (2011) y Separado!(2010), ambas producidas en Gales y escenificadas en la Patagonia. Propone que ambas se aprovechan de los códigos y tropos de la “road movie” y de la historia de emigración galesa a la Patagonia, para ubicar la cultura y lengua galesas en un contexto que es a la vez local y global. Palabras claves Gales - Patagonia - road movie - migración 1 Associate Professor of Comparative Literature, Brown University, Providence, Rhode Island, Estados Unidos. [email protected]. WHITFIELD PATAGONIAN ROAD MOVIES AND MIGRATION FROM WALES “The driving force propelling most road movies,” writes David Laderman, “is an embrace of the journey as a means of cultural critique” (Laderman 2002, 1). In the light of this analysis, this essay begins with two questions: in what ways might Patagonia lend itself- as setting, as landscape, as historically preconceived idea - to the road movie? And how do road movies set in Patagonia intersect with a history of immigrant travel to the region, specifically in the case of the storied nineteenth- century Welsh immigration to Chubut and the Esquel/ Trevelin area? My focus here is two bilingual (Spanish-Welsh) films, Patagonia and Separado!, released in 2011 and 2010 respectively in a context of much cultural production – in the form of novels, documentaries, radio programs etc. -

Launceston Lending Library 1

Launceston Lending Library 1 Shelf Title Author Category Audience Listing 22 Things a Woman Must Know if She Loves a Man with Simone Book SIM Adult Asperger's Syndrome (Donated item) National Autism A Parent's Guide to Evidence-Based Practice and Autism Book NAT Adult Center All Birds Have Anxiety Hoopmann Book HOO Adult An Asperger Leader's Guide to Living and Leading Change Bergemann Book BER Adult Asperger's on the Job (Must have advice for people with Asperger's or High Functioning Autism and their Employers, Simone Book SIM Adult Educators and advocates Aspergirls Simone Book SIM Adult Aspergirls Simone Book SIM Adult Autism All-Stars (How we use our Autism and Asperger Traits Santomauro Book SAN Adult to Shine in Life) Been There. Done That. Try This! An Aspie's Guide to Life on Attwood, Evans, Book ATT Adult Earth (Donated by Footprint Books) Lesko Build Your Own Life Lawson Book LAW Adult Coming Out Asperger: Diagnosis, Disclosure & Self- Murray Book MUR Adult Confidence Discover - A Resource for people planning for the future (A Endeavour Book END Adult National Disability Insurance Scheme Help Guide) Foundation Findings and Conclusions: National Standards Project, Phase National Autism Book NAT Adult 2 Center Helping Adults with Asperger's Syndrome Get & Stay Hired Bissonnette Book BIS Adult Neurotribes - The Legacy of Autism and how to think smarter Silberman Book SIL Adult about people who think differently Taking Care of Yourself and Your Family - A Resource Book Ashfield Book ASH Adult for Good Mental Health Emonds and The -

The Joy of Autism: Part 4

I also have a list of prominent unconfirmed participants, who should be confirmed shortly. I am looking for Canadian autistic persons to consider joining the board. Please send letters of interest to: [email protected] PERM ALINK POSTED BY ESTEE KLAR-WOLFOND AT 3/16/2006 11:19:00 AM 13 COM M ENTS LINKS TO THIS POST TUESDAY , M ARCH 14, 2006 The Difficulty of Knowing There is an old adage: Ignorance is Bliss. In the case of liberal eugenics, human genome research and ethics, some people might think this as they read on. As we come closer to discovering what makes us physically human, we come closer to becoming god-like. In the name of progress we fly higher and seek control. Apollo had a son called Phaethon, who was human. Phaethon nagged at Apollo to let him borrow the sun chariot and fly across the sky. Finally Apollo agreed. Phaethon proudly drove the sun chariot up into the sky, but then he lost control of the horses. The sun chariot dived towards the earth, burning everything. Finally Jupiter had to stop him with a thunder bolt. In the name of progress, human genetics, biotechnology and the economic engine that will profit dearly from it all, this movement will go on. To what end is yet to be determined. In the meantime, let’s keep talking about what this all means as my son hugs me from behind with his cherub smile this morning. I’ve been pondering my first pregnancy with Adam. The expectation of him. Needless to say, after thirty-six years of waiting, I was ecstatic. -

Autism in the Workforce

Autism in the Workforce By: David A. Holbrook A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the University Honors Program University of South Florida, St. Petersburg May 2, 2013 Thesis Director: Vicky Westra Founder of Artistas Café and Art for Autism University Honors Program University of South Florida St. Petersburg, Florida CERTIFICATE OF APPROVAL ___________________________ Honors Thesis ___________________________ This is to certify that the Honors Thesis of David A. Holbrook has been approved by the Examining Committee on May 2, 2013 as satisfying the thesis requirement of the University Honors Program Examining Committee: ___________________________ Thesis Director: Vicky Westra Founder of Artistas Café and Art for Autism ____________________________ Thesis Committee Member: Michael Glisson Manager of Artistas Café ___________________________ Thesis Committee Member: Stephanie Weber, Ph.D Professor, College of Education Abstract Individuals with Autism have tremendous challenges set out for them. Throughout their lives these individuals are told that they cannot succeed. They cannot achieve. Growing up with this mentality, these individuals enter adulthood without an outlet to give back to society. They are unable to find employment due to trepidations and misunderstandings of this disability brought on by a misleading and dangerous medical diagnosis. Unfortunately, this leads to them fading away within the crowd. They become a forgotten statistic amongst their generation. It is time for this ongoing trend to change. In this paper, the challenges and underlying factors of Autism brought on by the outlook of society are thoroughly examined. Moreover, the consequences of the resulting implications for society are similarly brought to light. This paper shows that the untapped capabilities and skills of these individuals are absolutely tremendous if and only if they are given a proper chance within society. -

PRESS Graphic Designer

© 2021 MARVEL CAST Natasha Romanoff /Black Widow . SCARLETT JOHANSSON Yelena Belova . .FLORENCE PUGH Melina . RACHEL WEISZ Alexei . .DAVID HARBOUR Dreykov . .RAY WINSTONE Young Natasha . .EVER ANDERSON MARVEL STUDIOS Young Yelena . .VIOLET MCGRAW presents Mason . O-T FAGBENLE Secretary Ross . .WILLIAM HURT Antonia/Taskmaster . OLGA KURYLENKO Young Antonia . RYAN KIERA ARMSTRONG Lerato . .LIANI SAMUEL Oksana . .MICHELLE LEE Scientist Morocco 1 . .LEWIS YOUNG Scientist Morocco 2 . CC SMIFF Ingrid . NANNA BLONDELL Widows . SIMONA ZIVKOVSKA ERIN JAMESON SHAINA WEST YOLANDA LYNES Directed by . .CATE SHORTLAND CLAUDIA HEINZ Screenplay by . ERIC PEARSON FATOU BAH Story by . JAC SCHAEFFER JADE MA and NED BENSON JADE XU Produced by . KEVIN FEIGE, p.g.a. LUCY JAYNE MURRAY Executive Producer . LOUIS D’ESPOSITO LUCY CORK Executive Producer . VICTORIA ALONSO ENIKO FULOP Executive Producer . BRAD WINDERBAUM LAUREN OKADIGBO Executive Producer . .NIGEL GOSTELOW AURELIA AGEL Executive Producer . SCARLETT JOHANSSON ZHANE SAMUELS Co-Producer . BRIAN CHAPEK SHAWARAH BATTLES Co-Producer . MITCH BELL TABBY BOND Based on the MADELEINE NICHOLLS MARVEL COMICS YASMIN RILEY Director of Photography . .GABRIEL BERISTAIN, ASC FIONA GRIFFITHS Production Designer . CHARLES WOOD GEORGIA CURTIS Edited by . LEIGH FOLSOM BOYD, ACE SVETLANA CONSTANTINE MATTHEW SCHMIDT IONE BUTLER Costume Designer . JANY TEMIME AUBREY CLELAND Visual Eff ects Supervisor . GEOFFREY BAUMANN Ross Lieutenant . KURT YUE Music by . LORNE BALFE Ohio Agent . DOUG ROBSON Music Supervisor . DAVE JORDAN Budapest Clerk . .ZOLTAN NAGY Casting by . SARAH HALLEY FINN, CSA Man In BMW . .MARCEL DORIAN Second Unit Director . DARRIN PRESCOTT Mechanic . .LIRAN NATHAN Unit Production Manager . SIOBHAN LYONS Mechanic’s Wife . JUDIT VARGA-SZATHMARY First Assistant Director/ Mechanic’s Child . .NOEL KRISZTIAN KOZAK Associate Producer . -

Mali Evans Editor

Shepperton Studios, Studios Road, Shepperton, Middx, TW17 OQD Tel: +44 (0)1932 571044 Website: www.saraputt.co.uk Mali Evans Editor TV Drama THE ENGLISH GAME 42 Management Production for Exec: Rory Aitken 6x60' NETFLIX Exec: Julian Fellowes Prod: Rhonda Smith Prod: Andy Morgan Dir: Brigitta Staermose JERUSALEM 42 Prod: Rhonda Smith Episodes 4, 5 & 6 Dir: Alex Winckler Dir: Dearbhla Walsh BANG Joio TV Prod: Catrin Lewis Defis Episodes 3 & 4 Dir: Ashley Way HINTERLAND/Y GWYLL Fiction Factory Prod: Gethin Scourfield Series II Prod: Ed Talfan Various Episodes HINTERLAND/Y GWYLL Fiction Factory Prod: Gethin Scourfield, Ed Talfan Series I Dir: Marc Evans, Rhys Powys Various Episodes DOORS OPEN Sprout Pictures Prod: Jon Finn TV Movie Dir: Marc Evans 1x120mins SHERLOCK Hartswood Films Prod: Sue Vertue Series I Dir: Euros Lyn 1x90mins Episode 2 - 'The Blind Banker' Winner: Televisual Bulldog Award for Best Editor AR Y TRACS Tidy Productions / Green Bay Media Prod: David Peet TV Movie Dir: Ed Talfan TIPYN O STAD Tonfedd / Eryri Production Prod: Pauline Williams Series I - VII Bafta Nominated Drama Series GWYFYN Fiction Factory Dir: Euros Lyn BAFTA award winning drama DIWRNOD HOLLOL MINDBLOWING HTV Dir: Euros Lyn HEDDIW BAFTA Nominated Drama YR ADUNIAD Boda Productions Dir: Ceri Sherlock TV Movie BAFTA Nomination for Best Editor NOSON YR HELIWR Back to Back Productions Dir: Peter Edwards TV Movie BAFTA winner for Best Editor Page 1 of 2 JERUSALEM 42 Dir: Rhonda Smith Editor Dir: Alex Winckler Episodes 4,5 & 6 Prod: Rhonda Smith Features THAT GOOD NIGHT -

Magic in the Moonlight

Sony Pictures Classics Presents in association with Gravier Productions, Inc. A Dippermouth Production in association with Perdido Productions & Ske-Dat-De-Dat Productions Magic in the Moonlight Written and Directed by Woody Allen East Coast Publicity West Coast Publicity Distributor 42West Block Korenbrot Sony Pictures Classics Scott Feinstein Max Buschman Carmelo Pirrone 220 West 42nd Street 110 S. Fairfax Ave, #310 Maya Anand 12th floor Los Angeles, CA 90036 550 Madison Ave New York, NY 10036 323-634-7001 tel New York, NY 10022 212-277-7555 323-634-7030 fax 212-833-8833 tel 212-833-8844 fax MAGIC IN THE MOONLIGHT Starring (in alphabetical order) Aunt Vanessa EILEEN ATKINS Stanley COLIN FIRTH Mrs. Baker MARCIA GAY HARDEN Brice HAMISH LINKLATER Howard Burkan SIMON McBURNEY Sophie EMMA STONE Grace JACKI WEAVER Co-starring (in alphabetical order) Caroline ERICA LEERHSEN Olivia CATHERINE McCORMACK George JEREMY SHAMOS Filmmakers Writer/Director WOODY ALLEN Producers LETTY ARONSON, p.g.a. STEPHEN TENENBAUM, p.g.a. EDWARD WALSON, p.g.a. Co-Producers HELEN ROBIN RAPHAËL BENOLIEL Executive Producer RONALD L. CHEZ Co-Executive Producer JACK ROLLINS Director of Photography DARIUS KHONDJI A.S.C., A.F.C Production Designer ANNE SEIBEL, ADC Editor ALISA LEPSELTER A.C.E. Costume Design SONIA GRANDE Casting JULIET TAYLOR PATRICIA DICERTO 2 MAGIC IN THE MOONLIGHT Synopsis Set in the 1920s on the opulent Riviera in the south of France, Woody Allen’s MAGIC IN THE MOONLIGHT is a romantic comedy about a master magician (Colin Firth) trying to expose a psychic medium (Emma Stone) as a fake.