Packer & Oswald

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Crowdfunding Is Hot

FEBRUARY 2017 Volume 33 Issue 02 DIGEST Mad Marketing Maven HOW MADMAN MUNTZ BUILT 3 EMPIRES Army Salutes Soldier’s Invention SAVING TIME AND MONEY Big Help for Tiny Babies BUSINESS MODEL: GIVING BACK IT DOESN’T TAKE AN EINSTEIN TO KNOW ... CROWDFUNDING IS HOT $5.95 FULTON, MO FULTON, PERMIT 38 PERMIT US POSTAGE PAID POSTAGE US PRSRT STANDARD PRSRT EDITOR’S NOTE Inventors DIGEST EDITOR-IN-CHIEF REID CREAGER ART DIRECTOR CARRIE BOYD New Website Adds CONTRIBUTORS STAFF SGT. ROBERT R. ADAMS To the Conversation STEVE BRACHMANN DON DEBELAK For many of us, there’s nothing like the traditional magazine experience—hold- JACK LANDER ing the original, glossy physical product in your hands; turning the paper pages; JEREMY LOSAW tearing out portions and/or pages to display or save; and having a flexible, por- GENE QUINN table keepsake that’s never susceptible to electronic or battery failure. JOHN G. RAU A publication that provides both this and a strong internet presence is the best EDIE TOLCHIN of both worlds. With that in mind, Inventors Digest recently updated its website GRAPHIC DESIGNER (inventorsdigest.com). We wanted to make our online content more attractive and JORGE ZEGARRA streamlined, with the goal of inviting even more readers. There’s also more content than ever before; we’re loading more current articles from each issue and going INVENTORS DIGEST LLC back through the archives to pull older ones. This is part of a larger mission: to make PUBLISHER the website a central hub for the Inventors LOUIS FOREMAN Digest community and encourage readers to become active participants in national VICE PRESIDENT, INTERACTIVE AND WEB conversations involving invented-related MATT SPANGARD subjects. -

Muntz, Earl 1932

Earl “Madman” Muntz Biography Earl “Madman” Muntz - Class of 1932 (did not actually graduate), - b. January 3, 1914 d. June 21, 1987 Earl “Madman” Muntz! The very name conjures up memories, for many, of one of the wildest and craziest entrepreneurs of the 20th century. First of the loud, nuts, in-your-face used car salesmen, in the 1940s his billboards blanketed Southern California screaming, “I wanna give ‘em away, but Mrs. Muntz won’t let me - SHE’S CRAZY!” and “I buy ‘em retail, sell ‘em wholesale - IT'S MORE FUN THAT WAY!” These billboards, plus a steady bombardment of radio ads, helped Muntz sell $76 million worth of automobiles in 1947, when a million dollars was real money. And his logo -- a caricature of Muntz wearing a black Napoleon hat and red BVDs -- seemed to be everywhere. He produced and sold Muntz TVs, cheap but functional sets that competed successfully in the marketplace with RCA, Philco and other electronic giants of the time. And his TV business made him a second multimillion dollar fortune. He produced the first American sports car -- the Muntz Jet. A beautiful, well-crafted, speedy car that was a precursor of Chevrolet's Corvette, the Muntz Jet was an aesthetic and mechanical success, but Muntz’s first financial disappointment. The Jets sold for $5,500 but they cost $6,500 to produce, and this at a time (the early 1950s) when a new Cadillac could be had for $3,200. Earl Muntz’s third fortune came in the 1960s when he invented the four-track car stereo, becoming the first major player in the soon-to-be-huge car stereo market. -

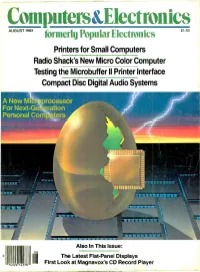

Computersalectronics AUGUST 1983 Formerly Popular Electronics $1.50

Computersalectronics AUGUST 1983 formerly Popular Electronics $1.50 Printers for Small Computers Radio Shack's New Micro Color Computer Testing the Microbuffer II Printer Interface Compact DiscDigital Audio Systems Also In This Issue: 08 o heT !Latest Flat -Panel Displays 1111 First 4024 1427 Look at Magnavox's CD Record Player www.americanradiohistory.comAmericanRadioHistory.Com You can wait for industry siandards to mandate improved performance. Or you can have it now on Maxell. The Gold Standard. The refinements of The Gold Standard, from clear and accurate. And lubricants reduce fric- oxide particles to lubricant to jacket, are uniquely tion between head and disk for a longer media Maxell. And therefore, so are the benefits. and head life. To house it, we then Our unique, uniform crystals assure dense a constructed a new jacket heat - oxide packing. So you begin with an origi- resistant to 140° F to withstand drive nal signal of extraordinary fidelity. A signal heat without warp or wear. And we safeguard in ways that leave industry created the floppy disk that standards in our wake. leads the industry in error -free performance and durability. An advanced binder bonds oxides to the base material preventing time All industry standards exist to and money- wasting dropouts. assure reliable performance. Calendering then smooths the sur- The Gold Standard expresses face for a read /write signal that stays a higher aim: perfection. mexeII. IT'S WORTH IT Computer Products Division, Maxell Corporation of America, 60 Oxford Drive, Moonachie, N.J. 07074 201 -440 -8020 Circle No. 30 on Free Information Card www.americanradiohistory.comAmericanRadioHistory.Com the KLH Solo Price Slashed List Price $199- Suggested Retail $169 January 1983 Dealer Cost $106 NOW $68 It's been killing us. -

Frequently Asked Questions - Alt.Collecting.8-Track-Tapes

Frequently Asked Questions - alt.collecting.8-track-tapes http://web.archive.org/web/20080603124715/http://www.8track... Information File and Frequently Asked Questions List FAQ Version 2.0 - Updated: March 2004 means New to this version back to 8-track Heaven Compiled by Malcolm Riviera with excellent assistance from Abigail Lavine, Our Lady of the 8-Tracks ([email protected]), Eric Wilson ([email protected]fi.net) and Ronald Bensley ([email protected]) and many others. Please send all additions, corrections, and suggestions to Malcolm Riviera at 8track@8trackheaven . Special thanks to Russ Forster for allowing me to lift freely from his fine publication "8-Track Mind" for many of the answers found below. Answers taken directly from the pages of "8-Track Mind" are denoted by [8TM - author name] at the beginning of the answer. This file is intended to provide a general information base and answer some frequently asked questions about 8-track tapes and other analog audio formats that are discussed on alt.collecting.8-track-tapes. It is hoped that this file will be useful to newcomers to the group and help fill in information gaps in the minds of experienced trackers. Table of Contents 1. 8-track tapes on Internet? Are you kidding? 2. Who invented the 8-track tape? 3. A. When did they stop making 8-tracks? B. Why did they stop making 8-tracks? C. Were 8-tracks popular internationally, or only in America? 4. What is "8-Track Mind"? 5. How does an 8-track work, anyway? 6. Where can I buy 8-track tapes and players? 7. -

NSN October 2018 B.Pub

Volume 18 Issue 10 October 1, 2018 My Pride and Joy Steve Allen’s Beautiful Barn Find This month we are reprinting a story from the September 2018 issue of the Road Race Lincoln Registry magazine, VIVA CARRERA, courtesy of Mike Denny, publisher. It is an interesting saga about one person’s passion for a very particular automobile, a 1953 Lincoln Capri. Here is the story as presented by the owner of this fine Lincoln — Steve Allen. Anyone with a passion for history and antique automobiles, inevitably finds them- selves daydreaming of their idea of the perfect barn find. The reality is that it rarely Welcome to the plays out as you envision. However, there are those exceptions that come along when you least expect it. Take my 1953 Lincoln Capri Convertible, for example. Northstar News, the My wife (Marie) and I had been discussing the long list of possibilities for what was monthly publication of to be the second car in our small collection. The problem was that we had such a wide the Northstar Region range of likes, we found it difficult to zero in on any one choice. of the Lincoln and One evening we were watching an old Lucille Ball, Desi Arnaz movie called the Continental Owners “Long Long Trailer.” It was a comedy of a newly married couple; who pulled an over- sized trailer across the country and it nearly broke up their marriage. The car that was Club. We value your used in the film was an early 1950s convertible. “That’s it!” Marie said, “That’s the kind opinions and appreciate of car I’d like own. -

DVD Players/Recorders and Camcorders

Brick 10005726: Analogue/Digital Converters Definition Includes any products that can be described/observed as a device which converts a standard analogue signal from a cd player, games console or cassette to a digital output, both optical and coaxial. Excludes products such as converter cassettes and swich–boxes. Type of Analogue/Digital Converter (20002648) Attribute Definition Indicates, with reference to the product branding, labelling or packaging, the descriptive term that is used by the product manufacturer to identify the type of analogue and/or digital converter. Attribute Values AUDIO CONVERTER UNCLASSIFIED (30002515) VIDEO CONVERTER (30013420) UNIDENTIFIED (30002518) (30013421) Page 1 of 198 Brick 10001467: Audio Headsets Definition Includes any products that can be described/observed as an audio receiver with small speakers that can be held to each ear by a headband or inserted into the ear, in order for one to listen to audio sounds. Specifically excludes communication headsets, which also contain a microphone for two–way communications. Excludes products such as Microphones, Converter Cassettes and Audio/Visual Cables. Corded/Cordless (20001116) Attribute Definition Indicates, with reference to the product branding, labelling or packaging, the descriptive term that is used by the product manufacturer to identify whether the product is connected to a base unit or power supply by a cord. Attribute Values CORDED (30007714) CORDLESS (30007715) UNIDENTIFIED (30002518) Signal Connection (20002597) Attribute Definition Indicates, -

BBC R&D Annual Review 2006-2007

Preparing the BBC for Creative Futures and Digital Britain. Ensuring it has the technology to remain relevant to licence fee payers and their evolving needs. BBC RESEARCH & INNOVATION ANNUAL REVIEW 1 Contents Foreword 4 NEW SERVICES CORE TECHNOLOGIES High Definition Television 6 Networks for Programme Production 30 Interactive Television for the On-demand World 8 Radio Systems 32 Online, On-demand, and On The Move 10 Video Compression – Dirac and Dirac Pro 34 Freeview Playback 13 Audio Compression 36 CONTENTS Serving our Audiences – User-centred Research 14 Digital Rights Management 37 PRODUCTION WORKING WITH US Production Magic 16 Collaborative Projects 38 D-3 Videotape Preservation System 19 Standards 40 Programme Production 20 BBC Information & Archives 43 Radio Spectrum for Production 23 The Innovation Forum 44 Future Media Innovation 45 DELIVERY Digital TV – Switchover 24 More Information 46 Digital TV – Architectures 26 Index 47 Audience Research 27 Credits and address 48 DAB and Digital Radio Mondiale 28 Kamaelia 29 2 APRIL 2006 – MARCH 2007 BBC RESEARCH & INNOVATION ANNUAL REVIEW 3 Foreword by Huw Williams, Head of Research & Innovation FOREWORD A new name Our achievements We continue to support our colleagues in production, with are about to be shown at the prestigious NAB broadcasters’ This review reflects a year of important I would like to pick out some of our significant achievements innovative solutions to make routine tasks easier and to encourage exhibition and conference in Las Vegas. We are also very close during the past year. creative programming.The Piero sports graphics system won the to trialling the delivery of digital TV and radio channels to 3G changes, with the renaming of our parent award for Innovation in Content Creation at IBC 2006. -

60Th-Anniversary-Boo

HORATIO ALGER ASSOCIATION of DISTINGUISHED AMERICANS, INC. A SIXTY-YEAR HISTORY Ad Astra Per Aspera – To the Stars Through Difficulties 1947 – 2007 Craig R. Barrett James A. Patterson Louise Herrington Ornelas James R. Moffett Leslie T. Welsh* Thomas J. Brokaw Delford M. Smith Darrell Royal John C. Portman, Jr. Benjy F. Brooks* Jenny Craig Linda G. Alvarado Henry B. Tippie John V. Roach Robert C. Byrd Sid Craig Wesley E. Cantrell Herbert F. Boeckmann, II Kenny Rogers Gerald R. Ford, Jr. Craig Hall John H. Dasburg Jerry E. Dempsey Art Buchwald Paul Harvey Clarence Otis, Jr. Archie W. Dunham Joe L. Dudley, Sr. S. Truett Cathy Thomas W. Landry* Richard M. Rosenberg Bill Greehey Ruth Fertel* Robert H. Dedman* Ruth B. Love David M. Rubenstein Chuck Hagel Quincy Jones Julius W. Erving J. Paul Lyet* Howard Schultz James V. Kimsey Dee J. Kelly Daniel K. Inouye John H. McConnell Roger T. Staubach Marvin A. Pomerantz John Pappajohn Jean Nidetch Fred W. O’Green* Christ Thomas Sullivan Franklin D. Raines Don Shula Carl R. Pohlad Willie Stargell* Kenneth Eugene Behring Stephen C. Schott Monroe E. Trout D.B. Reinhart* Henry Viscardi, Jr.* Doris K. Christopher Philip Anschutz Dennis R. Washington Robert H. Schuller William P. Clements, Jr. Peter M. Dawkins Carol Bartz Joe L. Allbritton Romeo J. Ventres John B. Connally, Esq.* J. R. “Rick” Hendrick, III Arthur A. Ciocca Walter Anderson Carol Burnett Nicholas D’Agostino* Richard O. Jacobson Thomas C. Cundy Dwayne O. Andreas Trammell Crow Helen M. Gray* Harold F. “Gerry” Lenfest William J. Dor Dorothy L. Brown Robert J. -

1952 Muntz Jet (Her Nickname Is “BUTTERCUP”)

1952 Muntz Jet (Her nickname is “BUTTERCUP”) M-130 This Muntz Jet is the 30th of 198 cars built car equipped with an ice chest and by The Muntz Car Company during the liquor cabinet in the rear arm seats. The period 1951 thru 1954. It is sometimes interior dashboard received an aircraft credited as the first high-performance like, Stewart-Warner instrumentation; personal luxury car built in America with as well as, what is considered Detroit’s the capability of doing 0 to 60 in 8.6 first modern console/bucket seat layout. seconds. Earl Muntz became the largest The Muntz was available in colors such Used Car Dealer in the world during as Boy Blue, Elephant Pink, Chartreuse, WWII, often paying servicemen $50 to Purple and Buttercup Yellow. Famous drive a car from the Midwest to California owners of the Muntz Jet include many where he reaped bigger margins. In Hollywood Celebrities such as: Clara 1949, he became a multi unit Kaiser Bow, Vic Damone, Grace Kelly and Dealer and was credited with selling Mickey Rooney. This M-130 Muntz Jet 22,000 out of 147,000 cars built that year. was initially purchased by the Pillsbury In 1950, he decided to build his own car, Family and later discovered in Michigan the Muntz Jet and purchased the Frank about 50 years ago. In 1952, a Muntz Kurtis Company and expanded this Jet sold for $5,500 while a 1952 Cadillac two seat creation into a four passenger Convertible sold for $3,800. Earl Muntz was a combination • Became a household name after WWII of PT Barnum’s hucksterism, when Bob Hope, Groucho Marx, Red a pinch of Thomas Edison’s Skelton, Jack Benny and others poked curiosity and President Trump’s early fun at his wacky sales pitches…thus the entrepreneurial adventures. -

Inventory Listing for "Digital Atsc". Click on the "Buy Now" Link to Purchase an Item

Inventory Listing for "Digital Atsc". Click on the "Buy Now" link to purchase an item. • Sansonic FT-300A ATSC Digital To Analog TV Converter w/Remote - New & Unused!!! ($13.00) - Buy Now • NEW SUNKEY DIGITAL TO ANALOG CONVERTER BOX HDTV SIGNAL ANTENNA DTV TV SK-801ATSC ($38.99) - Buy Now • COBY DTV-102 ATSC DIGITAL TV CONVERTER BOX TUNER * REMOTE * BRAND NEW **W CABLE ($29.95) - Buy Now • Artec USB Digital Cable QAM ATSC T18AR Tuner HDTV Card ($19.99) - Buy Now • Digital Prism ATSC-752 7" 480i HD LCD Television ($39.99) - Buy Now • Portable Digital/Analog TV Free-to-Air ATSC HDTV Telescopic Antenna w/Mag. base ($9.99) - Buy Now • Artec ATSC Indoor UHF VHF Digital HDTV TV AN2 Antenna ($10.99) - Buy Now • Digital Prism ATSC-710 7" LCD Television ($21.50) - Buy Now • USB Digital ATSC HDTV NTSC Video Capture TV FM Tuner ($32.95) - Buy Now • Car Digital TV Antenna Amplifier Signal Booster For Tuner Receiver DVB-T / ATSC ($16.49) - Buy Now • (New) Nfusion HD FTA Digital Satellite Receiver with ATSC Tuner and HD 1080i PVR ($139.99) - Buy Now • HDTV OUTDOOR DIGITAL ATSC TV DTV UHF VHF FM ANTENNA QUICK ASSEMBLY w/BRACKET ($49.00) - Buy Now • New Digital Flat TV indoor HDTV VHF UHF Antenna ATSC air ,4 Tuner PC Card HD ($9.99) - Buy Now • DIGITAL PRISM 3.5 HANDHELD DIGITAL LCD PORTABLE TV BLACK ATSC-301 ($19.95) - Buy Now • New Digital Flat TV indoor HDTV VHF UHF Antenna ATSC air ,4 Tuner PC Card HD ($10.10) - Buy Now • Artec USB Digital Cable QAM ATSC T19ARD Tuner HDTV Card Retail ($19.99) - Buy Now • AccessHD DTA1030D Digital Set-Top Converter -

Downloadsquad.Com

NORTHWESTERN UNIVERSITY TV Repair: New Media “Solutions” to Old Media Problems A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS for the degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Field of Screen Cultures By Bret Maxwell Dawson EVANSTON, ILLINOIS DECEMBER 2008 2 © Copyright by Bret Maxwell Dawson 2008 All rights reserved 3 ABSTRACT TV Repair: New Media “Solutions” to Old Media Problems Bret Maxwell Dawson Television’s history has at numerous points been punctuated by pronouncements that technological innovations will improve its programming, empower its audiences, and heal the injuries it has inflicted on American society. This enduring faith in the inevitability and imminence of television’s technological salvation is the subject of this dissertation. TV Repair offers a series of case studies of the promotion and reception of four new media technologies, each of which was at the moment of its introduction touted by members of various constituencies as a technological fix for television’s problems, as well as for the problems television’s critics have accused it of causing. At each of these moments of innovation, I explore the questions, fantasies, fears, and power struggles provoked by television’s convergence with new media, as well as the social, cultural, and economic contexts within which these mergers take place. Taken together, these case studies broaden our understanding of television’s technological history, and contribute to an ongoing dialogue about television’s place within studies of “new media.” In many contexts, television acts as a convenient shorthand for “old media,” connoting the passivity, centralization, and rigidity that new media promise to deliver us from. -

Annexes to the Report for the EC on a European Approach to Exploiting

Report for the European Commission ‘Exploiting the digital dividend’ – a European approach Annexes to the final report 14 August 2009 13496-294b ‘Exploiting the digital dividend’ – a European approach Contents Annex A: An inventory of national situations affecting the digital dividend in EU Member States A-1 A.1 Austria 1 A.2 Bulgaria 7 A.3 Cyprus 12 A.4 Czech Republic 17 A.5 Denmark 24 A.6 Estonia 29 A.7 Finland 33 A.8 France 39 A.9 Germany 48 A.10 Hungary 54 A.11 Ireland 63 A.12 Latvia 69 A.13 Lithuania 74 A.14 Luxembourg 81 A.15 Malta 87 A.16 Netherlands 94 A.17 Portugal 101 A.18 Romania 110 A.19 Slovakia 115 A.20 Slovenia 120 A.21 Spain 125 A.22 Sweden 131 A.23 UK 137 Annex B: A review of the situation regarding the digital dividend in neighbouring countries B-1 B.1 Croatia 1 B.2 Norway 3 B.3 Russia 8 B.4 Switzerland 10 B.5 Turkey 17 13496-294b ‘Exploiting the digital dividend’ – a European approach Annex C: A review of the situation regarding the digital dividend in non-European countries C-1 C.1 China 1 C.2 Japan 2 C.3 South Korea 6 C.4 USA 8 Annex D: Glossary Annex E: Stakeholders’ Hearings summary Annex F: First Member States’ workshop summary Annex G: Second Member States’ workshop summary 13496-294b ‘Exploiting the digital dividend’ – a European approach Copyright © 2009. Analysys Mason Limited has produced the information contained herein for the European Commission.