© 2017 Suraj Lakshminarasimhan All

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PRESIDENT Qmin Annivesary Menu 2021

derful menu One year anniversary special President, Mumbai - IHCL SeleQ�ons UP TO 12KMS CONTACTLESS ONLINE PAYMENT RADIUS DELIVERY VIA UPI SAFETY & SUSTAINABLE HYGIENE ASSURED PACKAGING THE KONKAN CAFE INR 2000 + taxes for 2 people | INR 3500 + taxes for 4 people | INR 5500 + taxes for 6 people Vegetarian APPETIZER VALLAI POO CUTLET Breaded deep-fried banana flower pa�y ARITHA PUNDI Tempered rice dumplings, a corgi specialty MAIN COURSE ANANAS GOJJU Sweet and sour pineapple curry KOLAM PATTANI Corn and green peas cooked che�nad style PADPE UPKARI Seasonal greens with coconut shavings PALAKURA PAPPU Len�l cooked with spinach GHEE RICE MALABARI PARATHA Flaky bread specialty from Malabar region NEER DOSA Pancake made from thin rice ba�er DESSERTS HOT JALEBI Deep fried flour swirls soaked in sugar syrup DODOL Toffee like sugar palm-based confec�on • Vegetarian • Non-Vegetarian All prices are in INR and exclusive of taxes. Allergies or food intolerance should be mentioned to the order taker on call. THE KONKAN CAFE INR 2000 + taxes for 2 people | INR 3500 + taxes for 4 people | INR 5500 + taxes for 6 people Non Vegetarian APPETIZER VEYINCINA ROYYALU Spicy fried prawns KORI KEMPU Chicken strips tossed in tempered yogurt MAIN COURSE FISH GASSI Mangalorean style fish curry MUTTON SUKHE A dry lamb prepara�on from Konkan PADPE UPKARI Seasonal greens with coconut shavings PALAKURA PAPPU Len�l cooked with spinach GHEE RICE MALABARI PARATHA Flaky bread specialty from Malabar region NEER DOSA Pancake made from thin rice ba�er DESSERTS HOT JALEBI Deep fried flour swirls soaked in sugar syrup DODOL Toffee like sugar palm-based confec�on • Vegetarian • Non-Vegetarian All prices are in INR and exclusive of taxes. -

Main Items: Appam: Pittu: Dosa: Naan Bread: Kothu Parotta

Main Items: Idiyappam Idly Chappathi Idiyappa Kothu Appam: Plain Appam Paal Appam Egg Appam Pittu: Plain Pittu Kuzhal Pittu Keerai Pittu Veg Pittu Kothu Egg Pittu Kothu Dosa: Plain Dosa Butter Plain Dosa Onion Masala Egg Dosa Masala Dosa Egg Cheese Dosa Onion Dosa Nutella Dosa Ghee Roast Plain Roast Naan Bread: Plain Naan Garlic Naan Cheese Naan Garlic Cheese Naan Kothu Parotta: Veg Kothu Parotta Egg Kothu Parotta Chicken Kothu Parotta Mutton Kothu Parotta Beef Kothu Parotta Fish Kothu Parotta Prawn Kothu Parotta RICE: Plain Rice Coconut Rice Lemon Rice Sambar Rice Tamarind Rice Curd Rice Tomato Rice Briyani: Veg Briyani Chicken Briyani Mutton Briyani Fish Briyani Prawn Briyani Fried Rice: Veg Fried Rice Chicken Fried Rice Seafood Fried Rice Mixed Meat Fried Rice Egg Fried Rice Fried Noodles: Veg Fried Noodles Chicken Fried Noodles Seafood Fried Noodles Mixed Meat Fried Noodles Egg Fried Noodles Parotta: Plain Parotta Egg Parotta EggCheese Parotta Chilli Parotta Nutella Parotta Live Item: Varieties of Appam Varieties of Parotta Varieties of Pittu Varieties of Dosa Mutton(Bone Boneless ▭): Mutton Curry (Srilankan & Indian Style) ▭ Mutton Devil ▭ Mutton Rasam ▭ Mutton Kuruma ▭ Mutton Varuval ▭ Pepper Mutton ▭ Chicken(Bone Boneless ▭): Chicken Curry (Srilankan & Indian Style) ▭ Chicken 65 ▭ Pepper Chicken ▭ Chicken Devil ▭ Chicken Tikka ▭ Butter Chicken ▭ Chicken Rasam ▭ Chicken Kuruma ▭ Chicken Varuval ▭ Chilli Chicken ▭ Chicken Lollipop Chicken Drumstick -

British Landscapes Featuring England, Scotland and Wales March 11 – 21, 2020

United National Bank presents… British Landscapes featuring England, Scotland and Wales March 11 – 21, 2020 For more information contact Linda Drew Johnson United National Bank (229) 377-7200 [email protected] 11 Days ● 13 Meals: 9 Breakfasts, 4 Dinners Per Person Rates*: Double $3,384 Single $4,419 Triple $3,344 Included in Price: Round Trip Air from Tallahassee Municipal, Air Taxes and Fees/Surcharges, Hotel Transfers for groups of 10 or more Not included in price: Cancellation Waiver and Insurance of $315 per person Upgrade your in-flight experience with Elite Airfare Additional rate of: Business Class $4,790 † Refer to the reservation form to choose your upgrade option * All Rates are Per Person and are subject to change IMPORTANT CONDITIONS: Your price is subject to increase prior to the time you make full payment. Your price is not subject to increase after you make full payment, except for charges resulting from increases in government-imposed taxes or fees. Once deposited, you have 7 days to send us written consumer consent or withdraw consent and receive a full refund. (See registration form for consent.) Collette’s Flagship: Collette’s tours open the door to a world of amazing destinations. Marvel at must-see sights, sample regional cuisine, stay in centrally located hotels and connect with new and captivating cultures. These itineraries offer an inspiring and easy way to experience the world, where an expert guide takes care of all the details. 956435 Collette Experiences Must-See Inclusions Culinary Inclusions Behold the Crown Jewels See the quintessential Enjoy a private dinner at of Scotland on a guided sights of London with a Hall's Croft, a 400-year- tour of Edinburgh Castle. -

Donna Lee Brien Writing About Food: Significance, Opportunities And

Donna Lee Brien Writing about Food: Significance, opportunities and professional identities Abstract: Food writing, including for cookbooks and in travel and food memoirs, makes up a significant, and increasing, proportion of the books written, published, sold and read each year in Australia and other parts of the English-speaking world. Food writing also comprises a similarly significant, and growing, proportion of the magazine, newspaper and journal articles, Internet weblogs and other non-fiction texts written, published, sold and read in English. Furthermore, food writers currently are producing much of the concept design, content and spin-off product that is driving the expansion of the already popular and profitable food-related television programming sector. Despite this high visibility in the marketplace, and while food and other culinary-related scholarship are growing in reputation and respectability in the academy, this considerable part of the contemporary writing and publishing industry has, to date, attracted little serious study. Moreover, internationally, the emergent subject area of food writing is more often located either in Food History and Gastronomy programs or as a component of practical culinary skills courses than in Writing or Publishing programs. This paper will, therefore, investigate the potential of food writing as a viable component of Writing courses. This will include a preliminary investigation of the field and current trends in food writing and publishing, as well as the various academic, vocational and professional opportunities and pathways such study opens up for both the students and teachers of such courses. Keywords: Food Writing – Professional Food Writers – Creative and Professional Writing Courses – Teaching Creative and Professional Writing Biographical note Associate Professor Donna Lee Brien is Head of the School of Arts and Creative Enterprise at Central Queensland University, and President of the AAWP. -

Nutritional Information

NUTRITIONAL INFORMATION GF - gluten free DF – dairy free Chicken Soups Energy Kcal Fat g of which sat g Carb g of which sugar Fibre Protein Salt Free from Allergens Andaman Island Spiced Chicken 405 27 15 17.3 5.9 3.9 21.5 0.5 GF, DF SulPhites Californian Chicken Succotash 418 19 8.1 35 9.6 7.5 27 3.1 GF Milk, Celery Jammin Jamaican Jerk Chicken 392 25.3 15.2 19.4 4.2 6.7 18.4 0.5 GF, DF Celery Soto Ayam - Indonesian Chicken 414 27.5 15.3 15.5 5.4 7.9 22.2 0.6 GF, DF SulPhites Sri Lankan Chicken & Red Lentil 448 28.3 16.2 16.4 5.8 6.5 23.7 0.5 GF, DF Thai Style Crushed Chilli Chicken 579 65.1 47.2 10.4 8.9 2.7 27.6 0.8 DF Crustaceans, Soya, Fish, Gluten, SulPhites Vietnamese Chicken & Sweet Potato 496 14.4 5 23.3 10 5.6 17.7 0.5 GF, DF Fish Turkey Soups Turkey Chilli N/A GF, DF Celery NUTRITIONAL INFORMATION GF - gluten free DF – dairy free Beef Soups Energy Kcal Fat g of which sat g Carb g of which sugar Fibre Protein Salt Free From Allergens Dan Dan Sezchchaun Beef Broth 261 15.5 2.9 9.2 0.5 0.5 20.9 0.4 DF Gluten, Fish, SulPhites Kashmiri Beef 375 21.5 7.5 21.5 3.9 2.9 22.4 0.8 GF Milk, Mustard Keema - Spiced Mince Beef 432 21.8 8 16.1 7.6 4.6 13.8 0.4 GF Milk, Celery Malay Massman Beef 546 37 17 26 6 6 29 3.6 GF, DF Peanuts Moghul Beef 369 22 8.8 23 5.4 4.8 21 3.1 GF Milk, Celery Nusa Smokehouse Chill con Carne 319 14.5 3.2 21.4 8.1 8.1 21.7 0.8 GF, DF Celery Jungli Beef 513 39 21 19 4.4 3.5 22 3.1 GF, DF ShrimP (shrimP Paste) NUTRITIONAL INFORMATION GF - gluten free DF – dairy free Pork Soups Energy Kcal Fat g of which sat g Carb -

Using Regional Food Memoirs to Develop Values-Based Food Practices

BRIEN AND MCALLISTER — “SUNSHINE HAS A TASTE, YOU KNOW” “SUNSHINE HAS A TASTE, YOU KNOW” Using regional food memoirs to develop values-based food practices Donna Lee Brien Central Queensland University Margaret McAllister Central Queensland University Abstract Alongside providing a source of entertainment, the growth in food media of all kinds reflects a genuine consumer interest in knowing more about food. While there is culinary information available that serves to educate in relation to food-related practices (shopping, food preparation, cooking, eating out) in ways that can serve to build confidence and enthusiasm, we propose that, in order for new food practices to be not only adopted, but sustained, consumers need to hone and develop personal values that will complement their technical and practical knowledge. This is the marrying of evidence-based and values-based practice that makes for sustained change in personal habits and practices (Fulford 2008). This discussion proposes that regional food memoirs – and specifically those by food producers – can arouse interest and curiosity, build knowledge in regional food systems, and connect consumers to food Locale: The Australasian-Pacific Journal of Regional Food Studies Number 5, 2015 —32— BRIEN AND MCALLISTER — “SUNSHINE HAS A TASTE, YOU KNOW” producers and production. This, we propose, can activate consumers to develop and embed the kind of learning that reinforces a belief in the need to be an ‘authentic consumer’. An authentic consumer is one who knows themselves, their own needs and desires, and makes choices consciously rather than automatically. It follows that an authentic food consumer is engaged with their local food systems and aware of the challenges that confront these systems. -

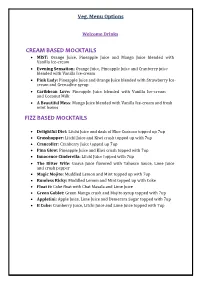

Cream Based Mocktails

Veg. Menu Options Welcome Drinks CREAM BASED MOCKTAILS MIST: Orange Juice, Pineapple Juice and Mango Juice blended with Vanilla Ice-cream Evening Sensation: Orange Juice, Pineapple Juice and Cranberry juice blended with Vanilla Ice-cream Pink Lady: Pineapple Juice and Orange Juice blended with Strawberry Ice- cream and Grenadine syrup Caribbean Love: Pineapple Juice blended with Vanilla Ice-cream and Coconut Milk A Beautiful Mess: Mango Juice blended with Vanilla Ice-cream and fresh mint leaves FIZZ BASED MOCKTAILS Delightful Diet: Litchi Juice and dash of Blue Curacao topped up 7up Grasshopper: Litchi Juice and Kiwi crush topped up with 7up Crancoller: Cranberry Juice topped up 7up Pina Glow: Pineapple Juice and Kiwi crush topped with 7up Innocence Cinderella: Litchi Juice topped with 7up The Bitter Wife: Guava Juice flavored with Tabasco Sauce, Lime Juice and crush pepper Magic Mojito: Muddled Lemon and Mint topped up with 7up Rumless Ricky: Muddled Lemon and Mint topped up with Coke Float it: Coke float with Chat Masala and Lime Juice Green Goblet: Green Mango crush and Mojito syrup topped with 7up Appletini: Apple Juice, Lime Juice and Demerara Sugar topped with 7up B Cube: Cranberry Juice, Litchi Juice and Lime Juice topped with 7up Vegetarian Starters Paneer Tikka Achari/ Paneer Kesri Tikka Paneer Tikka Hariali / Paner Ajwaini Tikka/ Paneer Shaslik/ Paneer Tawa Kebab/ Paneer Makai Roll Palak Aur Anar ki Tikki/ Palak ki Shikampuri/ Mutter Shammi Kebab Aloo Aur makai ki Tikki / Subz Shammi Kebab/ Dahi ke kebab Cocktail Samosa/ Mutter ki Shikampuri Golden fried Baby corn/ Crispy fried vegetables Salt & Papper/ Crispy Thai Cauliflower with peanut Sauce/ Chilli Paneer/ Sechwan Paneer/ Sesame Paneer Vegetarian Soup Tamatar dhaniya shorba Chesse Corn Tomato Soup Cream of Tomato Soup Tomato Basil Soup Palak Ka Shorba Dal aur nimbu ka Shorba Rasam Badam Ka Shorba Vegetable Hot & Sour Soup Veg. -

Meals in English Speaking Countries

Meals in English speaking countries the UK People in the UK usually have breakfast, lunch and dinner at home. Some of the English national meals are: Toad in the hole Full English breakfast Shepherd’s pie Spotted dick Fish and chips Black pudding Tikka masala Apple crumble with cream Now match the dishes with the correct photo. Divide the dishes into sweet and savoury ones. Pracovní list byl vytvořen v rámci projektu "Nová cesta za poznáním", reg. č. CZ.1.07/1.5.00/34.0034, za finanční podpory Evropského sociálního fondu a rozpočtu ČR. Uvedená práce (dílo) podléhá licenci Creative Commons Uveďte autora-Nevyužívejte dílo komerčně-Zachovejte licenci 3.0 Česko English people eat roast meat. It is usually served with boiled or roast potatoes, peas, Brussels sprouts, carrots, Yorkshire pudding, and gravy. English cuisine has been influenced by the communities coming to the UK, namely the Indian one. That’s why one of the popular meals in the UK is Tikka masala. Many people and children in particular eat at fast-food restaurants. The obesity is therefore increasing. This is one of the reasons a well-known chef, Jamie Oliver, started his campaign, called Food Revolution, to change the way children eat. the USA Many people think American food means fast-food. But it is the ethnic food that was brought to the USA by immigrants, such as Italians, Mexicans, or Greeks. So there is a great variety. Also Chinese and Indian take-aways are very popular. At the same time, Americans love to eat out. Americans work long hours, so they are often too tired to cook. -

A Dinner at the Governor's Palace, 10 September 1770

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1998 A Dinner at the Governor's Palace, 10 September 1770 Mollie C. Malone College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the American Studies Commons Recommended Citation Malone, Mollie C., "A Dinner at the Governor's Palace, 10 September 1770" (1998). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539626149. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-0rxz-9w15 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A DINNER AT THE GOVERNOR'S PALACE, 10 SEPTEMBER 1770 A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of American Studies The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by Mollie C. Malone 1998 APPROVAL SHEET This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts 'JYIQMajl C ^STIclU ilx^ Mollie Malone Approved, December 1998 P* Ofifr* * Barbara (farson Grey/Gundakerirevn Patricia Gibbs Colonial Williamsburg Foundation TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS iv ABSTRACT V INTRODUCTION 2 HISTORIOGRAPHY 5 A DINNER AT THE GOVERNOR’S PALACE, 10 SEPTEMBER 1770 17 CONCLUSION 45 APPENDIX 47 BIBLIOGRAPHY 73 i i i ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I want to thank Professor Barbara Carson, under whose guidance this paper was completed, for her "no-nonsense" style and supportive advising throughout the project. -

2018 Corporate Menus Gourmet Food for Every Event Let's Get Started!

2018 Corporate Menus Gourmet Food for Every Event From quick and healthy lunchtime drop offs, to full-service fundraisers and galas, The Gourmet Kitchen has you covered! Spice up your work week with fresh ingredients, exceptional service, and gourmet menu offerings. With dedicated event coordinators and professional chef team, we're with you every step of the way to make each event, no matter how small, a success! Let’s get started! Contact an event coordinator today to order your perfect menu. 303.465.2635 thegourmetkitchen.biz [email protected] Corporate Lunch Menus Cold Menus | $12 per person + taxes and delivery Assorted Gourmet Boxed Lunches (served buffet style or as boxed lunches, minimum of 6 sandwiches of one kind) Choose from: Breads: • Turkey • Sour Dough • Ham • Wheat • Roast Beef • Gluten Free Bread • Veggie Fresh Fruit | a bowl of fresh, seasonal fruit Chips | individual bags of assorted potato chips Chocolate Chip Cookies | fresh from the oven! Salad Bar Curried Quinoa Salad | cooked quinoa mixed with chopped veggies and spices Mixed Greens | Lettuce, spinach, arugula, kale Toppings: Dressings: • Feta cheese • Italian • Mushrooms • Balsamic Vinaigrette • Red onions • Chipotle Ranch • Black beans • Blue Cheese • Grilled chicken Hot Menus | $15 per person + taxes and delivery. Served Buffet Style or as boxed lunches. Dinner portions are $5 per person more American Kansas Style BBQ Beef Brisket | tender shredded beef brisket with a sweet Kansas style BBQ sauce Dinner Rolls Jicama-Apple Cole Slaw Garden Salad| mixed -

The East India Company: Agent of Empire in the Early Modern Capitalist Era

Social Education 77(2), pp 78–81, 98 ©2013 National Council for the Social Studies The Economics of World History The East India Company: Agent of Empire in the Early Modern Capitalist Era Bruce Brunton The world economy and political map changed dramatically between the seventeenth 2. Second, while the government ini- and nineteenth centuries. Unprecedented trade linked the continents together and tially neither held ownership shares set off a European scramble to discover new resources and markets. European ships nor directed the EIC’s activities, it and merchants reached across the world, and their governments followed after them, still exercised substantial indirect inaugurating the modern eras of imperialism and colonialism. influence over its success. Beyond using military and foreign policies Merchant trading companies, exem- soon thereafter known as the East India to positively alter the global trading plified by the English East India Company (EIC), which gave the mer- environment, the government indi- Company, were the agents of empire chants a monopoly on all trade east of rectly influenced the EIC through at the dawn of early modern capital- the Cape of Good Hope for 15 years. its regularly exercised prerogative ism. The East India Company was a Several aspects of this arrangement to evaluate and renew the charter. monopoly trading company that linked are worth noting: Understanding the tension in this the Eastern and Western worlds.1 While privilege granting-receiving relation- it was one of a number of similar compa- 1. First, the EIC was a joint-stock ship explains much of the history of nies, both of British origin (such as the company, owned and operated by the EIC. -

Exploration of Portuguese-Bengal Cultural Heritage Through Museological Studies

Exploration of Portuguese-Bengal Cultural Heritage through Museological Studies Dr. Dhriti Ray Department of Museology, University of Calcutta, Kolkata, West Bengal, India Line of Presentation Part I • Brief history of Portuguese in Bengal • Portuguese-Bengal cultural interactions • Present day continuity • A Gap Part II • University of Calcutta • Department of Museology • Museological Studies/Researches • Way Forwards Portuguese and Bengal Brief History • The Portuguese as first European explorer to visit in Bengal was Joao da Silveira in 1518 , couple of decades later of the arrival of Vasco Da Gama at Calicut in 1498. • Bengal was the important area for sugar, saltpeter, indigo and cotton textiles •Portuguese traders began to frequent Bengal for trading and to aid the reigning Nawab of Bengal against an invader, Sher Khan. • A Portuguese captain Tavarez received by Akbar, and granted permission to choose any spot in Bengal to establish trading post. Portuguese settlements in Bengal In Bengal Portuguese had three main trade points • Saptagram: Porto Pequeno or Little Haven • Chittagong: Porto Grande or Great Haven. • Hooghly or Bandel: In 1599 Portuguese constructed a Church of the Basilica of the Holy Rosary, commonly known as Bandel Church. Till today it stands as a memorial to the Portuguese settlement in Bengal. The Moghuls eventually subdued the Portuguese and conquered Chittagong and Hooghly. By the 18th century the Portuguese presence had almost disappeared from Bengal. Portuguese settlements in Bengal Portuguese remains in Bengal • Now, in Bengal there are only a few physical vestiges of the Portuguese presence, a few churches and some ruins. But the Portuguese influence lives on Bengal in other ways— • Few descendents of Luso-Indians (descendants of the offspring of mixed unions between Portuguese and local women) and descendants of Christian converts are living in present Bengal.