Collins2018.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Anya Gallaccio

ANYA GALLACCIO Born Paisley, Scotland 1963 Lives London, United Kingdom EDUCATION 1985 Kingston Polytechnic, London, United Kingdom 1988 Goldsmiths' College, University of London, London, United Kingdom SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2019 NOW, The Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, Edinburgh, Scotland Stroke, Blum and Poe, Los Angeles, CA 2018 dreamed about the flowers that hide from the light, Lindisfarne Castle, Northumberland, United Kingdom All the rest is silence, John Hansard Gallery, Southampton, United Kingdom 2017 Beautiful Minds, Thomas Dane Gallery, London, United Kingdom 2015 Silas Marder Gallery, Bridgehampton, NY Lehmann Maupin, New York, NY Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego, San Diego, CA 2014 Aldeburgh Music, Snape Maltings, Saxmundham, Suffolk, United Kingdom Blum and Poe, Los Angeles, CA 2013 ArtPace, San Antonio, TX 2011 Thomas Dane Gallery, London, United Kingdom Annet Gelink, Amsterdam, The Netherlands 2010 Unknown Exhibition, The Eastshire Museums in Scotland, Kilmarnock, United Kingdom Annet Gelink Gallery, Amsterdam, The Netherlands 2009 So Blue Coat, Liverpool, United Kingdom 2008 Camden Art Centre, London, United Kingdom 2007 Three Sheets to the wind, Thomas Dane Gallery, London, United Kingdom 2006 Galeria Leme, São Paulo, Brazil One art, Sculpture Center, New York, NY 2005 The Look of Things, Palazzo delle Papesse, Siena, Italy Blum and Poe, Los Angeles, CA Silver Seed, Mount Stuart Trust, Isle of Bute, Scotland 2004 Love is Only a Feeling, Lehmann Maupin, New York, NY 2003 Love is only a feeling, Turner Prize Exhibition, -

Tate Report 08-09

Tate Report 08–09 Report Tate Tate Report 08–09 It is the Itexceptional is the exceptional generosity generosity and and If you wouldIf you like would to find like toout find more out about more about PublishedPublished 2009 by 2009 by vision ofvision individuals, of individuals, corporations, corporations, how youhow can youbecome can becomeinvolved involved and help and help order of orderthe Tate of the Trustees Tate Trustees by Tate by Tate numerousnumerous private foundationsprivate foundations support supportTate, please Tate, contact please contactus at: us at: Publishing,Publishing, a division a divisionof Tate Enterprisesof Tate Enterprises and public-sectorand public-sector bodies that bodies has that has Ltd, Millbank,Ltd, Millbank, London LondonSW1P 4RG SW1P 4RG helped Tatehelped to becomeTate to becomewhat it iswhat it is DevelopmentDevelopment Office Office www.tate.org.uk/publishingwww.tate.org.uk/publishing today andtoday enabled and enabled us to: us to: Tate Tate MillbankMillbank © Tate 2009© Tate 2009 Offer innovative,Offer innovative, landmark landmark exhibitions exhibitions London LondonSW1P 4RG SW1P 4RG ISBN 978ISBN 1 85437 978 1916 85437 0 916 0 and Collectionand Collection displays displays Tel 020 7887Tel 020 4900 7887 4900 A catalogue record for this book is Fax 020 Fax7887 020 8738 7887 8738 A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. DevelopDevelop imaginative imaginative education education and and available from the British Library. interpretationinterpretation programmes programmes AmericanAmerican Patrons Patronsof Tate of Tate Every effortEvery has effort been has made been to made locate to the locate the 520 West520 27 West Street 27 Unit Street 404 Unit 404 copyrightcopyright owners ownersof images of includedimages included in in StrengthenStrengthen and extend and theextend range the of range our of our New York,New NY York, 10001 NY 10001 this reportthis and report to meet and totheir meet requirements. -

Michael Landy Born in London, 1963 Lives and Works in London, UK

Michael Landy Born in London, 1963 Lives and works in London, UK Goldsmith's College, London, UK, 1988 Solo Exhibitions 2017 Michael Landy: Breaking News-Athens, Diplarios School presented by NEON, Athens, Greece 2016 Out Of Order, Tinguely Museum, Basel, Switzerland (Cat.) 2015 Breaking News, Michael Landy Studio, London, UK Breaking News, Galerie Sabine Knust, Munich, Germany 2014 Saints Alive, Antiguo Colegio de San Ildefonso, Mexico City, Mexico 2013 20 Years of Pressing Hard, Thomas Dane Gallery, London, UK Saints Alive, National Gallery, London, UK (Cat.) Michael Landy: Four Walls, Whitworth Art Gallery, Manchester, UK 2011 Acts of Kindness, Kaldor Public Art Projects, Sydney, Australia Acts of Kindness, Art on the Underground, London, UK Art World Portraits, National Portrait Gallery, London, UK 2010 Art Bin, South London Gallery, London, UK 2009 Theatre of Junk, Galerie Nathalie Obadia, Paris, France 2008 Thomas Dane Gallery, London, UK In your face, Galerie Paul Andriesse, Amsterdam, The Netherlands Three-piece, Galerie Sabine Knust, Munich, Germany 2007 Man in Oxford is Auto-destructive, Sherman Galleries, Sydney, Australia (Cat.) H.2.N.Y, Alexander and Bonin, New York, USA (Cat.) 2004 Welcome To My World-built with you in mind, Thomas Dane Gallery, London, UK Semi-detached, Tate Britain, London, UK (Cat.) 2003 Nourishment, Sabine Knust/Maximilianverlag, Munich, Germany 2002 Nourishment, Maureen Paley/Interim Art, London, UK 2001 Break Down, C&A Store, Marble Arch, Artangel Commission, London, UK (Cat.) 2000 Handjobs (with Gillian -

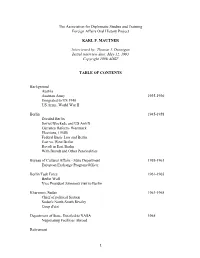

Mautner, Karl.Toc.Pdf

The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project KARL F. MAUTNER Interviewed by: Thomas J. Dunnigan Initial interview date: May 12, 1993 opyright 1998 ADST TABLE OF CONTENTS Background Austria Austrian Army 1 35-1 36 Emigrated to US 1 40 US Army, World War II Berlin 1 45-1 5, Divided Berlin Soviet Blockade and US Airlift .urrency Reform- Westmark Elections, 01 4,1 Federal Basic 2a3 and Berlin East vs. West Berlin Revolt in East Berlin With Brandt and Other Personalities Bureau of .ultural Affairs - State Department 1 5,-1 61 European E5change Program Officer Berlin Task Force 1 61-1 65 Berlin Wall 6ice President 7ohnson8s visit to Berlin 9hartoum, Sudan 1 63-1 65 .hief of political Section Sudan8s North-South Rivalry .oup d8etat Department of State, Detailed to NASA 1 65 Negotiating Facilities Abroad Retirement 1 General .omments of .areer INTERVIEW %: Karl, my first (uestion to you is, give me your background. I understand that you were born in Austria and that you were engaged in what I would call political work from your early days and that you were active in opposition to the Na,is. ould you tell us something about that- MAUTNER: Well, that is an oversimplification. I 3as born on the 1st of February 1 15 in 6ienna and 3orked there, 3ent to school there, 3as a very poor student, and joined the Austrian army in 1 35 for a year. In 1 36 I got a job as accountant in a printing firm. I certainly couldn8t call myself an active opposition participant after the Anschluss. -

A Brief History of the Arts Catalyst

A Brief History of The Arts Catalyst 1 Introduction This small publication marks the 20th anniversary year of The Arts Catalyst. It celebrates some of the 120 artists’ projects that we have commissioned over those two decades. Based in London, The Arts Catalyst is one of Our new commissions, exhibitions the UK’s most distinctive arts organisations, and events in 2013 attracted over distinguished by ambitious artists’ projects that engage with the ideas and impact of science. We 57,000 UK visitors. are acknowledged internationally as a pioneer in this field and a leader in experimental art, known In 2013 our previous commissions for our curatorial flair, scale of ambition, and were internationally presented to a critical acuity. For most of our 20 years, the reach of around 30,000 people. programme has been curated and produced by the (founding) director with curator Rob La Frenais, We have facilitated projects and producer Gillean Dickie, and The Arts Catalyst staff presented our commissions in 27 team and associates. countries and all continents, including at major art events such as Our primary focus is new artists’ commissions, Venice Biennale and dOCUMEntA. presented as exhibitions, events and participatory projects, that are accessible, stimulating and artistically relevant. We aim to produce provocative, Our projects receive widespread playful, risk-taking projects that spark dynamic national and international media conversations about our changing world. This is coverage, reaching millions of people. underpinned by research and dialogue between In the last year we had features in The artists and world-class scientists and researchers. Guardian, The Times, Financial Times, Time Out, Wall Street Journal, Wired, The Arts Catalyst has a deep commitment to artists New Scientist, Art Monthly, Blueprint, and artistic process. -

April 2007 � Liebe Leserinnen Und Leser, Neu Auf Der Potsdamer

Die Stadtteilzeitung Ihre Zeitung für Schöneberg - Friedenau - Steglitz Zeitung für bürgerschaftliches Engagement und Stadtteilkultur Ausgabe Nr. 40 - April 2007 www.stadtteilzeitung-schoeneberg.de L Liebe Leserinnen und Leser, Neu auf der Potsdamer Ick sitze inner Küche... Immerhin haben sich doch einige Ring frei für die von Ihnen an den alten Spruch von den Klopsen noch erinnert - Schöneberger! darunter sogar eine Neuberliner (Friedenauer) deutsch-französi- Jetzt geht's Berg auf für Kin- sche Familie! Versprochen ist der, Jugendliche, Erwachsene versprochen, hier ist er: und Senioren aus Schöne- Ick sitze da und esse Klops berg! Schnell Umziehen, Auf- Mit eenmal kloppt's wärmen und dann ab in den Ick kieke, staune, wund're mir Ring 'ne Runde Boxen… Uff eenmal isse uff, die Tür! Nanu, denk ick, ick denk nanu Vor kurzem, am 22. Februar, Jetzt isse uff, erst war se zu? eröffnete in der Potsdamer Ick jehe raus und kieke Straße 152 der Boxclub "Wir und wer steht draußen: icke! aktiv. Boxsport & mehr.". Es ist ein soziales Kiezprojekt und Wen wundert's, dass es diverse gleichzeitig ein neuer Treffpunkt Versionen davon gibt? Wir ha- für sportliche Schöneberger. Auf ben sozusagen eine mittlere ge- ca. 500 Quadratmetern werden wählt, und Elfriede Knöttke unterschiedliche Kurse für Jung freut sich über die Grüße und ist und Alt angeboten. Ehrenamt- ganz glücklich, denn jetzt hat sie Die General-Pape-Straße beginnt (oder endet) am neuen Bahnhof Südkreuz Foto: Thomas Protz lich organisiert und für die ihre Wette gewonnen und ihr Nutzer kostenlos. Es wird sicher Günter muß eine Woche lang L jeder was für seinen "Sportge- abwaschen! Ein Areal mit Überraschungen: v. -

Im Geiste Der Beiden Testamente Aus De

RUNDBRIEF zur Förderung der Freundschaft zwischen dem Alten und dem Neuen Gottesvolk — im Geiste der beiden Testamente 11111V. Folge 1951/1952 Freiburg, Dezember 1951 Nummer 12/15 4 SONDER-AUSGABE: FRIEDE MIT ISRAEL Aus dem Inhalt: 1. Erste Schritte auf dem Wege zum Frieden mit Israel von Karlheinz Schmidthüs Seite 3 a) ,Wo ift dein Bruder Abel?' Ansprache zur Einweihung des Gedächtnismales auf dem alten Judenfriedhof in Schlüchtern von Wilhelm Praesent am 7. August 1949 Seite 4 b) „Gib, o Gott, daß in keines Menschen Herz Haß aufsteige !" Rede von Landesrabbiner Dr. Robert R.Geis auf dem Jüdischen Friedhof anläßlidi der Einweihung des Gedenksteins für die jüdischen Opfer des Nationalsozialismus. Kassel, Sonntag, den 25. Juni 1950. Seite 5 c) „Wir bitten Israel um Frieden" von Eridt Lüth Seite 7 d) Nahum Goldmann an Erich Lüth Seite 8 e) Die Erklärungen Bundeskanzler Dr. Adenauers und der Parteien zur Wieder- gutmachung . Seite 9 n Rabbiner Dr. Leo Bai& zur Regierungs- und Parteienerklärung .. Seite 11 g) Resolution des Zentralrats der Juden in Deutschland über die deutsche Regierungs- erklärung . . Seite 11 h) Jüdischer Weltkongreß zur deutschen Regierungserklärung Seite 12 1) Israel antwortet auf die Erklärung der Bundesregierung zum jüdisch-deutschen Verhältnis , Seite 12 k) „Ich schenke Deutschland den Frieden !" Aus einem offenen Brief an Erich Lüth und Rudolf Küstermeier von ihrem 1(2-Leidensgefährten Israel Gelber aus Jerusalem Seite 13 2. Deutschland und Israel von E. L. Ehrlich Seite 14 3. Der neue Staat Israel und die Christenheit. Bericht von der Düsseldorfer Tagung des Deutschen evangelischen Ausschusses für Dienst an Israel, 26. Februar bis 2. -

The Free German League of Culture

VOLAJRUME JOURNAL 0 NO.9 SEPTEMBER 200 The Free German League of Culture oday, it is hard to imagine that 1939 at an informal meeting held at the the AJR was once overshadowed Hampstead home of the refugee lawyer T by other organisations claiming and painter Fred Uhlman. It was formally to represent the refugees from Germany constituted at a meeting on 1 March 1939, and Austria in Britain. Yet this was the when Uhlman was appointed chairman, case during the wartime years, when and four honorary presidents were the Free German League of Culture elected: the artist Oskar Kokoschka, the (FGLC, Freier Deutscher Kulturbund) drama critic Alfred Kerr, the writer Stefan was active as the body representing the Zweig and the film director Berthold refugees from Germany, and the Austrian Viertel. The presence of these eminent Centre those from Austria. These were names indicates the importance of culture politically inspired organisations, aiming to the League and to its political aims. It to represent all anti-Nazi refugees from had close relations with the small group Germany or Austria irrespective of of German Communists who had fled to religion or race, unlike the AJR, whose London. Its strategy mirrored Communist constituency was the Jewish refugees tactics during the Popular Front period of irrespective of nationality. the 1930s: to use a programme of cultural Both the FGLC and the Austrian Centre and artistic events to enlist the support of were founded in 1939, just before the FGLC honorary president Oskar Kokoschka a broad spectrum of left-liberal, culturally outbreak of war. -

Manifestopdf Cover2

A Manifesto for the Book Sarah Bodman and Tom Sowden A Manifesto for the Book Sarah Bodman and Tom Sowden with an edited selection of interviews, essays and case studies from the project What will be the canon for the artist’s book in the 21st Century? 1 A Manifesto for the Book Published by Impact Press at The Centre for Fine Print Research University of the West of England, Bristol February 2010 Free download from: http://www.bookarts.uwe.ac.uk/canon.htm This publication is a result of a project funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council from March 2008 - February 2010: What will be the canon for the artist’s book in the 21st Century? The AHRC funds postgraduate training and research in the arts and humanities, from archaeology and English literature to design and dance. The quality and range of research supported not only provides social and cultural benefits but also contributes to the economic success of the UK. For further information on the AHRC, please see the website www.ahrc.ac.uk ISBN 978-1-906501-04-4 © 2010 Publication, Impact Press © 2010 Images, individual artists © 2010 Texts, individual authors Editors Sarah Bodman and Tom Sowden The views expressed within A Manifesto for the Book are not necessarily those of the editors or publisher. Impact Press, Centre for Fine Print Research UWE, Bristol School of Creative Arts Kennel Lodge Road, Bristol BS3 2JT United Kingdom Tel: +44 (0) 117 32 84915 Fax: +44 (0) 117 32 85865 www.bookarts.uwe.ac.uk [email protected] [email protected] 2 Contents Interview with Eriko Hirashima founder of LA LIBRERIA artists’ bookshop in Singapore 109 A Manifesto for the Book Sarah Bodman and Tom Sowden 5 Interview with John Risseeuw, proprietor of his own Cabbagehead Press and Director of ASU’s Pyracantha Interview with Radoslaw Nowakowski on publishing his own Press, Arizona State University, USA 113 books and artists’ books “non-describing the world” since the 70s in Dabrowa Dolna, Poland. -

The Sculpted Voice an Exploration of Voice in Sound Art

The Sculpted Voice an exploration of voice in sound art Author: Olivia Louvel Institution: Digital Music and Sound Art. University of Brighton, U.K. Supervised by Dr Kersten Glandien 2019. Table of Contents 1- The plastic dimension of voice ................................................................................... 2 2- The spatialisation of voice .......................................................................................... 5 3- The extended voice in performing art ........................................................................16 4- Reclaiming the voice ................................................................................................20 Bibliography ....................................................................................................................22 List of audio-visual materials ............................................................................................26 List of works ....................................................................................................................27 List of figures...................................................................................................................28 Cover image: Barbara Hepworth, Pierced Form, 1931. Photographer Paul Laib ©Witt Library Courtauld Institute of Art London. 1 1- The plastic dimension of voice My practice is built upon a long-standing exploration of the voice, sung and spoken and its manipulation through digital technology. My interest lies in sculpting vocal sounds as a compositional -

Adapted to the Cinema by Harold Pinter for Jerry Schatzberg (1989): from (Auto)Biography to Politics

Interfaces Image Texte Language 37 | 2016 Appropriation and Reappropriation of Narratives Reunion, a Novella by Fred Uhlman (1971) adapted to the Cinema by Harold Pinter for Jerry Schatzberg (1989): from (auto)biography to politics Isabelle Roblin Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/interfaces/298 DOI: 10.4000/interfaces.298 ISSN: 2647-6754 Publisher: Université de Bourgogne, Université de Paris, College of the Holy Cross Printed version Date of publication: 1 January 2016 Number of pages: 163-179 ISSN: 1164-6225 Electronic reference Isabelle Roblin, “Reunion, a Novella by Fred Uhlman (1971) adapted to the Cinema by Harold Pinter for Jerry Schatzberg (1989): from (auto)biography to politics”, Interfaces [Online], 37 | 2016, Online since 19 March 2018, connection on 06 January 2021. URL: http://journals.openedition.org/interfaces/298 ; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/interfaces.298 Les contenus de la revue Interfaces sont mis à disposition selon les termes de la Licence Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International. 163 REUNION, A NOVELLA BY FRED UHLMAN (1971) ADAPTED TO THE CINEMA BY HAROLD PINTER FOR JERRY SCHATZBERG (1989): FROM (AUTO)BIOGRAPHY TO POLITICS Isabelle Roblin Before starting on the analysis of the ways in which Harold Pinter and Jerry Schatzberg transformed and re appropriated Fred Uhlman’s text to make it into a film, it is necessary to sum up what the text is about. The plot of Uhlman’s largely autobiographical novella is quite simple. It is about the short and intense, but ultimately impossible, friendship between two fifteen-year-old school boys during the rise of the Nazi party in Stuttgart in the early 1930s, and more exactly between February 1932 and January 1933. -

ABGABE Letztfassung IV

DIPLOMARBEIT Titel der Diplomarbeit „Kunst basteln. Die Wurstserie von Fischli und Weiss im Kontext der Zürcher Szene 1979/80“ Verfasserin Simone Mathys-Parnreiter angestrebter akademischer Grad Magistra der Philosophie (Mag. Phil.) Wien, 2010 Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt: A315 Studienrichtung lt. Studienblatt: Kunstgeschichte Betreuer: Prof. Friedrich Teja Bach Thanks to the Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, for kindly providing me with photographic images of the Wurstserie . Dank an Bice Curiger für Ihre Zeit und ihr grosszügiges Zurverfügungstellen von Dokumentationsmaterial ihrer Ausstellung „Saus und Braus. Stadtkunst“ und Dank an Dora Imhof von der Universität Zürich für die Möglichkeit an Künstlerinterviews im Rahmen des Oral History Projektes teilzunehmen. 2 INHALTSVERZEICHNIS 1) EINLEITUNG .......................................................................................................................5 2) WURSTSERIE (1979) ..........................................................................................................8 2.1 Bricolage und Dilettantismus .......................................................................................28 2.2 Verortung im Gesamtwerk ...........................................................................................40 3) KONTEXT: ZÜRCHER SZENE 1979/1980 ....................................................................47 3.1 Punk und seine Bedeutung für Fischli/Weiss ..............................................................48 3.1.1 Das Projekt Migro (um 1980)