River Navigation in Indiana

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

E.3-IDNR Roster of Navigable Waterways in Indiana

APPENDIX E.3 IDNR Roster of Navigable Waterways in Indiana Nonrule Policy Documents NATURAL RESOURCES COMMISSION Information Bulletin #3 July 1, 1992 SUBJECT: Roster of Indiana Waterways Declared Navigable I. NAVIGABILITY Property rights relative to Indiana waterways often are determined by whether the waterway is "navigable". Both common law and statutory law make distinctions founded upon whether a river, stream, embayment, or lake is navigable. A landmark decision in Indiana with respect to determining and applying navigability is State v. Kivett, 228 Ind. 629, 95 N.E.2d 148 (1950). The Indiana Supreme Court stated that the test for determining navigability is whether a waterway: was available and susceptible for navigation according to the general rules of river transportation at the time [1816] Indiana was admitted to the Union. It does not depend on whether it is now navigable. .The true test seems to be the capacity of the stream, rather than the manner or extent of use. And the mere fact that the presence of sandbars or driftwood or stone, or other objects, which at times render the stream unfit for transportation, does not destroy its actual capacity and susceptibility for that use. A modified standard for determining navigability applies to a body of water which is artificial. The test for a man-made reservoir, or a similar waterway which did not exist in 1816, is whether it is navigable in fact. Reed v. United States, 604 F. Supp. 1253 (1984). The court observed in Kivett that "whether the waters within the State under which the lands lie are navigable or non-navigable, is a federal" question and is "determined according to the law and usage recognized and applied in the federal courts, even though" the waterway may not be "capable of use for navigation in interstate or foreign commerce." Federal decisions applied to particular issues of navigability are useful precedents, regardless of whether the decisions originated in Indiana or another state. -

Unconsolidated Aquifer Systems of Hancock County, Indiana

Unconsolidated Aquifer Systems of Hancock County, Indiana by Glenn E. Grove Division of Water, Resource Assessment Section November 2005 Three unconsolidated aquifer systems have been mapped in Hancock County: the New Castle Till; the White River and Tributaries Outwash Subsystem; and the New Castle Complex. All three systems comprise sediments deposited by, or resulting from, glaciers, glacial meltwaters, and post-glacial precipitation events. Boundaries of these aquifer systems are commonly gradational and individual aquifers may extend across aquifer system boundaries. However, a relatively distinct boundary occurs where the White River Outwash and Tributaries Subsystem abuts the relatively steep valley walls of the Big Blue River. Outside of the valley of the Big Blue River, nearly the entire county has more than 100 feet of unconsolidated materials overlying the bedrock. Unconsolidated deposits are especially thick in the eastern third of the county where the sediments are commonly greater than 200 feet and in places (north of Cumberland) greater than 300 feet thick. However, in the Big Blue River valley there are a few areas where the unconsolidated deposits are less than 50 feet in thickness. Most unconsolidated deposits contain some sand or gravel and only a few dry holes have been reported in Hancock County. All the aquifer systems are typically capable of supplying domestic wells. The New Castle Till Aquifer System and the New Castle Complex Aquifer System are, in most places, capable of producing high-capacity wells. There are areas in the New Castle Complex where sand and gravel deposits are of sufficient thickness and extent to constitute major ground-water resources capable of supplying large municipal, industrial, and irrigation needs. -

Potentiometric Surface Map of the Unconsolidated Aquifers of Hancock County, Indiana

Mitchell E. Daniels, Jr., Governor Department of Natural Resources Division of Water Robert E. Carter Jr., Director Potentiometric Surface Map 18-A POTENTIOMETRIC SURFACE MAP OF THE UNCONSOLIDATED AQUIFERS OF HANCOCK COUNTY, INDIANA Hancock County, Indiana is located in the central portion of the state. The majority of the R. 7 E. R. 8 E. R. 6 E. R. 7 E. county is situated in the East Fork White River Basin, however, a relatively small area in the northwest section is located within the White and West Fork White River Basin. C k o e u e n r t The Potentiometric Surface Map (PSM) of the unconsolidated aquifers of Hancock County y 0 C 0 0 R 10 40 85 11 was mapped by contouring the elevations of 1745 static water-levels reported on well records 8 9 9 8 9 r 13 0 o N 7 12 2 a a «¬ 11 0 C 9 a 9 0 d 0 s 109 0 g 3 8 o received primarily over a 50 year period. These wells are completed in aquifers at various 8 10 h «¬ 7 8 4 0 u 0 u 5 v 12 9 8 i 9 6 11 0 n S 1 l l 9 depths, and typically, under confined conditions (bounded by impermeable layers above and 9 0 0 e t 9 R y 10 6 E 8 d Fortville R below the water bearing formation). However, some wells were completed under unconfined o County Road 1000 N a (not bounded by impermeable layers) settings. -

Hancock County Part B Update 10 2010

NPDES PHASE II MS4 GENERAL PERMIT STORM WATER QUALITY MANAGEMENT PLAN PART B: BASELINE CHARACTERIZATION REPORT UPDATE HANCOCK COUNTY, INDIANA PERMIT #INR040128 OCTOBER 30, 2010 NPDES PHASE II STORM WATER QUALITY MANAGEMENT PLAN (SWQMP) PART B: BASELINE CHARACTERIZATION REPORT UPDATE Prepared for: Hancock County, Indiana October 2010 Prepared by: Christopher B. Burke Engineering, Ltd. National City Center, Suite 1368-South 115 W. Washington Street Indianapolis, Indiana 46204 CBBEL Project Number 03-463 DISCLAIMER: Exhibits and any GIS data used within this report are not intended to be used as legal documents or references. They are intended to serve as an aid in graphic representation only. Information shown on exhibits is not warranted for accuracy or merchantability. Hancock County, Indiana NPDES Phase II SWQMP Part B: Baseline Characterization Report Update TABLE OF CONTENTS Page # 1.0 INTRODUCTION 1 2.0 LAND USE WITHIN MS4 AREA 2 2.1 DESCRIPTION OF MS4 AREA 2 2.2 POPULATION DATA 2 2.3 LAND USE DATA 3 2.4 WATERSHEDS WITHIN MS4 AREA 3 2.5 SUMMARY OF LAND USE EVALUATIONS 4 3.0 SENSITIVE AREA 5 3.1 ERODIBLE SOIL 5 3.2 SOIL SUITABLITY FOR SEPTIC SYSTEMS 5 3.3 NATURAL HERITAGE DATA 6 3.4 WETLANDS 6 3.5 OUTSTANDING AND EXCEPTIONAL USE WATERS 7 3.6 ESTABLISHED TMDL WATERS 7 3.7 RECREATIONAL WATERS 7 3.8 PUBLIC DRINKING WATER SOURCES 7 3.9 SUMMARY OF SENSITIVE AREA CONCLUSIONS 8 4.0 SUMMARY OF EXISTING MONITORING DATA 9 4.1 INDIANA INTEGRATED WATER MONITORING AND ASSESSMENT REPORT 9 4.2 UNITED STATES GEOLOGIC SURVEY (USGS) STUDIES 9 4.3 STREAM REACH CHARACTERIZATION EVALUATION REPORT 10 4.4 CLEAN WATER ACT CHAPTER 319 GRANT STUDIES 11 4.5 HEALTH DEPARTMENT STUDIES 11 5.0 IDENTIFICATION AND ASSESSMENT OF EXISTING BMPs 12 i Christopher B. -

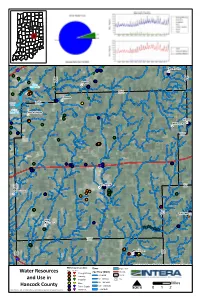

Water Resources and Use in Hancock County

S" ¸ # ¸ ¸ ¸ # # 9 # Markleville -6 ¸ I§¨¦ # S" n ¸ # y o r n n s i n o ¸ o # t d e l s i i a H d M m a a M H Ingalls ¸ ¸ # Geist # ¸ # Reservoir S" ¸ ¸ ¸ ¸ # # # # ¸ eek # ¸ # r Madison ¸ # l C l Hancock ¸ # a F ¸ Fortville # Hamilton S" Hamilton Hancock Marion Geist Reservoir McCordsville ¸ # ¸ S" # Shirley ¸ # Wilkinson S" S" Hancock ¸ # Henry ¸ # ¸ # ¸ # ¸ # ¨¦§I-70 ¸ # ¸ # ¸ ¸ # # S" k n c Henry o o i Greenfield c r Rush n a a M H S" Cumberland ¸ S" # ¸ # k c h o s c u n R a ¸ ¸ ¸ ¸ # # # H Carthage # ¸ # S" New Palestine " S Big Blue River ¸ # Hancock Shelby y h b l s y n e Morristown u b o l h i R r e S a h M S S" I ¨¦§-7 4 ¸ # Source: Esri, DigitalGlobe, GeoEye, i-cubed, USDA, USGS, AEX, Getmapping, Aerogrid, IGN, IGP, swisstopo, and the GIS User Community Withdrawal Location River Major Lakes ¸ # ¸ # WELL INTAKE 7Q2 Flow (MGD) Interstate ¸ Water Resources # Energy/Mining <10 MGD County ¸ # Industry Irrigation 10 - 50 MGD S" City ¸ and Use in # 50 - 100 MGD ¸ # Misc. Miles 100 - 500 MGD ¸ Hancock County # Public Supply N 0 1 2 Data Sources: U.S. Geological Survey and Indiana Department of Natural Resources Rural Use > 500 MGD Mitchell E. Daniels, Jr., Governor Department of Natural Resources Division of Water Kyle J. Hupfer, Director Aquifer Systems Map 20-B R. 7 E. R. 8 E. R. 6 E. R. 7 E. illage Br E V oo k 5 2 6 3 1 d 11 SR a 8 9 10 o 7 R 12 The occurrence of bedrock aquifers depends on the original composition of the rocks and 2 11 E 10 R S O 3 8 9 a 8 0 t 7 y s 12 t R 11 0 u subsequent changes which influence the hydraulic properties. -

Low-Flow Characteristics of Indiana Streams

LOW-FLOW CHARACTERISTICS OF INDIANA STREAMS By James A. Stewart U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Open-File Report 82-1007 Prepared in cooperation with INDIANA STATE BOARD OF HEALTH and the INDIANA DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES Indianapolis, Indiana 1983 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR JAMES G. WATT, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Dallas L. Peck, Director For additional information Copies of this report can write to: be purchased from: District Chief Open-File Services Section U.S. Geological Survey, WRD Western Distribution Branch 6023 Guion Road, Suite 201 Box 25425, Federal Center Indianapolis, Indiana 46254 Denver, Colorado 80225 (Telephone: (303) 234-5888) CONTENTS Page Abstract................................................................. 1 Introduction............................................................. 1 Purpose and scope.................................................... l Acknowledgments...................................................... 2 Physiography and geology................................................. 2 Northern zone........................................................ 2 Central zone......................................................... 4 Southern zone........................................................ 4 Precipitation............................................................ 5 Low-flow-frequency analysis.............................................. 5 Continuous-record stations........................................... 5 Partial-record stations............................................. -

Fishes of the White River Basin, Indiana

FISHES OF THE WHITE RIVER BASIN, U INDIANA G U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Since 1875, researchers have reported 158 species of fish belonging to 25 families in the White River Basin. Of these species, 6 have not been reported since 1900 and 10 have not been reported since 1943. Since the 1820's, fish communities in the White River Basin have been affected by the alteration of stream habitat, overfishing, the introduction of non-native species, agriculture, and urbanization. Erosion resulting from conversion of forest land to cropland in the 1800's led to siltation of streambeds and resulted in the loss of some silt- sensitive species. In the early 1900's, the water quality of the White River was seriously degraded for 100 miles by untreated sewage from the City of Indianapolis. During the last 25 years, water quality in the basin has improved because of efforts to control water pollu tion. Fish communities in the basin have responded favorably to the improved water quality. INTRODUCTION In 1991, the U.S. Geological Survey began the National Water- Quality Assessment (NAWQA) Program. The long-term goals of the NAWQA Program are to describe the status and trends in the quality of a large, representative part of the Nation's surface- and ground-water resources and to provide a sound, scientific understanding of the pri mary natural and human factors affecting the quality of these resources (Hirsch and others, 1988). The White River Basin in Indiana was among the first 20 river basins to be studied as part of this program. -

Driftwood Watershed

Driftwood 8 Digit Watershed (05120204) Delaware Total Acres: 745,529 Driftwood Watershed - 12 Digit HUCs Indiana Counties Acres Bartholomew County: 46,028 Brown County: 6,158 Hancock County: 171,554 Madison 0102 Henry County: 120,138 Hamilton Johnson County: 126,929 Madison County: 4,149 Marion County: 32,282 Hamilton Rush County: 74,139 0101 Shelby County: 164,152 Grey shaded 12-digit watersheds fall completely 0104 or partially within Indiana. Shaded 12-digit 0402 0401 watershed names and acres are on page 2. Hancock 0103 Henry 4-digit labels represent the last 4 numbers of the 12-digit watershed code. 0403 *Please note, all acres are approximate.* 0301 0107 1 0 Winter 2013 8 0106 0 0302 02 05 0105 0802 0 Marion 8 0405 0 0501 3 0108 0201 0404 3 0 5 0804 0 0504 0203 0202 0303 Fayette 0701 Rush 0702 0805 0204 0304 0205 0 0703 6 0 2 0601 Johnson 0806 0603 Shelby 0704 0604 0807 Franklin 0705 0902 0903 0901 Decatur MI 0904 Bartholomew Brown IL IN OH Ripley Jennings 0 2.25 4.5 9 Miles ± KY Number - 12 Digit HUC Last 4 Digits of HUC Name - 12 Digit HUC Acres within Indiana 051202040101 0101 Moonshine Run-Little Blue river 11,997.0 051202040102 0102 Summit Lake-Big Blue River 15,149.3 051202040103 0103 Elliott Run-Big Blue River 11,212.4 051202040104 0104 Jakes Branch-Duck Creek 17,500.6 051202040105 0105 Knightstown Spring-Buck Creek 12,582.6 051202040106 0106 Westwood Run-Big Blue River 16,127.0 051202040107 0107 MontgomeryMontgomery CreekCreek 15, 573. -

A History of American Settlement at Camp Atterbury

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Faculty Publications Anthropology, Department of 1-2010 A History of American Settlement at Camp Atterbury Steven D. Smith University of South Carolina - Columbia, [email protected] Chris J. Cochran Engineer Research and Development Center Champaign IL Construction Engineering Research Lab Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/anth_facpub Part of the Anthropology Commons Publication Info Published in 2010. © 2010, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Construction Engineering Research Laboratories. This Book is brought to you by the Anthropology, Department of at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ERDC/CERL TR-10-3 ERDC/CERL TR-10-3 The History of American Settlement at Camp Atterbury Steven D. Smith and Chris J. Cochran January 2010 Construction Engineering Laboratory Research Approved for public release; distribution is unlimited. ERDC/CERL TR-10-3 January 2010 The History of American Settlement at Camp Atterbury Steven D. Smith South Carolina Institute of Archaeology and Anthropology 1321 Pendleton Street Columbia, SC 29208 Chris J. Cochran Construction Engineering Research Laboratory U.S. Army Engineer Research and Development Center 2902 Newmark Drive Champaign, IL 61822 Final Report Approved for public release; distribution is unlimited. Prepared for Camp Atterbury Joint Maneuver Training Center Environmental Office PO Box 5000 Edinburgh, IN 46124 ERDC/CERL TR-10-3 ii Abstract: This report details the history of 19th and 20th century farm and community settlement within the Camp Atterbury Joint Maneuver Training Center, IN. -

William B. Palmer Collection, 1951–1990

Collection # P 0206 OM 0505 WILLIAM B. PALMER COLLECTION, 1951–1990 Collection Information Biographical Sketch Scope and Content Note Series Contents Cataloging Information Processed by Marilyn Rader and Dorothy A. Nicholson March 2014 revised May 2014 Manuscript and Visual Collections Department William Henry Smith Memorial Library Indiana Historical Society 450 West Ohio Street Indianapolis, IN 46202-3269 www.indianahistory.org COLLECTION INFORMATION VOLUME OF Photographs: 9 boxes of photographs, 1 box OVA COLLECTION: photographs, 1 OVA color photograph, 1 OVB photograph Negatives: 1 box 4x5 acetate negatives, 1 box of 120 mm acetate negatives, 6 boxes of 35 mm acetate negatives Manuscript Materials: 2 document cases, 1 OM folder Artifacts: 1 artifact COLLECTION 1951–1990 DATES: PROVENANCE: Heritage Photo Services, Indianapolis, Ind. 2002 Linda J. Kelso, Indianapolis, Ind. 2002 RESTRICTIONS: The negatives and color photograph are in cold storage and researchers must request them a day in advance and may view the negatives with the assistance of Library Staff. COPYRIGHT: The photographs in this collection were taken while William Palmer was an employee of the Indianapolis News. REPRODUCTION Permission to reproduce or publish material in this collection RIGHTS: must be obtained from the Indianapolis Star, copyright owner of the Indianapolis News. ALTERNATE FORMATS: RELATED HOLDINGS: ACCESSION 2002.0342, 2002.0424 NUMBER: NOTES: BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH William Beckner Palmer (1913–1997) was a staff photographer for the Indianapolis News. His assignments were random; society, sports, fire, accident, or human interest. Palmer had a standing assignment of “pick ups,” that meant he could take photographs of whatever he found of interest to the readers. -

Flood-Inundation Maps for the Driftwood River and Sugar Creek Near Edinburgh, Indiana

Prepared in cooperation with Camp Atterbury Joint Maneuver Training Center, Edinburgh, Indiana Flood-Inundation Maps for the Driftwood River and Sugar Creek near Edinburgh, Indiana Pamphlet to accompany Scientific Investigations Map 3210 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Cover. Hendricks Ford Bridge over the Driftwood River, near Edinburgh, Ind. (Photograph by Chad Menke, USGS, January 2011). Flood-Inundation Maps for the Driftwood River and Sugar Creek near Edinburgh, Indiana By Kathleen K. Fowler, Moon H. Kim, and Chad D. Menke Prepared in cooperation with Camp Atterbury Joint Maneuver Training Center, Edinburgh, Indiana Pamphlet to accompany Scientific Investigation Map 2012–3210 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior KEN SALAZAR, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey Marcia K. McNutt, Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2012 For more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment, visit http://www.usgs.gov or call 1–888–ASK–USGS. For an overview of USGS information products, including maps, imagery, and publications, visit http://www.usgs.gov/pubprod To order this and other USGS information products, visit http://store.usgs.gov Any use of trade, product, or firm names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this report is in the public domain, permission must be secured from the individual copyright owners to reproduce any copyrighted materials contained within this report. Suggested citation: Fowler, K.K., Kim, M.H., and Menke, C.D., 2012, Flood-inundation maps for the Driftwood River and Sugar Creek near Edinburgh, Indiana: U.S. -

Hancock County Trails Plan 7-18 Table of Contents

FINAL REPORT November 5, 2018 PREPARED BY: BUTLER, FAIRMAN & SEUFERT, INC. & HEALTH BY DESIGN 7-16 LETTER OF INTRODUCTION Butler Fairman & Seufert, Inc. (BF&S) and Health By Design (HbD) are pleased to present the Hancock County Trails Master Plan to the citizens and administrators of Hancock County, Indiana, and the municipalities of Cumberland, Fortville, Greenfield, McCordsville, New Palestine, Shirley, and Wilkinson. This report is the product of a collaborative effort by the Executive Committee, BF&S design professionals, HbD design professionals, the Steering Committee, local merchants and members of the Hancock County community. It is intended to serve as a guide for future alternative transportation and recreational development within Hancock County. Each bicycle facility route, pedestrian improvement, program recommendation, and policy recommendation was thoroughly researched. Decisions were based on a process that consisted of a county-wide inventory and analysis process, design synthesis, public input, and development of design standards before ultimately reaching the master plan stage. The resulting recommendations are the best solutions to initiating a county-wide bicycle and pedestrian network. The plan is intended to be a “living document” and will serve as a long lasting foundation for future alternative transportation development BF&S and HbD are very appreciative to have been able to assist Hancock County in this planning effort and we look forward to the implementation of these recommendations. Respectfully submitted on the 28th day of August, 2018, Butler, Fairman, & Seufert, Inc. Alan L. Hamersly, P.E. Jason G. Griffin, P.L.A. Health By Design Kim Irwin, MPH HANCOCK COUNTY TRAILS PLAN 7-18 TABLE OF CONTENTS A.