Lpbcurrentnom Oldibm.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THOUGRT Am SENATE REFUSES a TARIFF on OIL for FIFTH TIME

THE WEATHER NET PRESS RUN Porecaat by i>. & Weatiiw Boreau, . Hartford. AVERAGE DAILV CIRCDIATION for tile Montii of February, 19S0 Fair and much colder tonfgffat; Saturday increasing cloudiness and 5 , 5 0 3 coatina^ cold. Memben of the AnOlt Biurcan of Clrcnlatloaa PRICE THREE CENTS SOUTH MANCHESTER, CONN., F*RH)AY, MARCH 21, 1930. TWENTY PAGES VOL. XLIV., NO. 146. (Classified Advertising on Page 18) FAMOUS FIDDLER AS “SILVER BULLET” TUNED UP AT DAYTONA BEACH PfflSONUQUOR SENATE REFUSES ALCOm PLEA SAVED BY WIFE FOR RECORD DASH » THOUGRT am FOR RETURN OF Mellie Dunham Gets Out ofj A TARIFF ON OIL Blazing Home in Time But} " m His Prizes and Relics Are| INDEmHERE CONViaSOX’d Burned. i Norway, Maine, March 21— 'M FOR FIFTH TIME (AP) —^Mellie Dunham, famous Arthur Aitken Dies Sudden fiddler was saved by his aged 5#^ Lalone, Moulthrope and Lan helpmate, “Gram,” from a fire which destroyed their century ly After Drinking Hooch, Watson, Republican Leader, dry to Be Brought Back old farmhouse on Crockett’s JOBLESS SnUATION Ride today, but his many “fid But Inyestigation Shows Announces That Upp^r X dles” and prizes, relics and , To This State to Face antiques were lost. , -V BAD AS IN ’14 “Gram,” awoke at 2 a. m. to find a room adjoining their bed Booze Not Direct Cause. House Shall Stay In Ses ^ Other Charges. room ablaze. She awakened Mellie and three grandchildren Arthur Aitken, unmarried, an out- i So Says New York State Of- sion Tomorrow Until It in smother room. side labor time keeper employed Hartford, Conn., March 21.—(AP) Assisted by “Gram,” Mellie —State’s Attorney Hugh M. -

Wcra Annual Report 2016

WCRA ANNUAL REPORT 2016 Meeting Washington’s Affordable Housing Needs Through Partnership Washington Community Reinvestment Association MISSION STATEMENT To be a catalyst for the creation and preservation of affordable housing in Washington state. To expand resources for real estate based community development in Washington state. To be a voice for its member financial institutions on affordable housing and community development issues. To provide a dynamic risk sharing vehicle to maximize private investment in community development throughout Washington state. To operate within a strategic and financially prudent structure. To work with public sector entities to promote public/private partnerships that achieve maximum leverage of public dollars. To provide value to its members and the communities they serve that will generate and sustain support for WCRA's long term operation and success. TABLE OF CONTENTS Featured Projects Lilac Place ................................................................................................................................................4 Glennwood Townhomes .......................................................................................................................6 Kirkland Avenue Townhomes ..............................................................................................................8 Valle Lindo II ..........................................................................................................................................10 Galbraith Gardens ................................................................................................................................11 -

Manufacturing Employer Survey

Manufacturing Employer Survey MARCH 2016 MANUFACTURING ADVANCEMENT PATHWAYS PROJECT MANUFACTURING EMPLOYER SURVEY I 1 This report was commissioned by SkillUp Washington, the workforce education funders’ collaborative at the Seattle Foundation. For more information about SkillUp, please visit www.skillupwa.org. Many thanks to the Boeing Company for supporting the Manufacturing Advancement Pathways Project, which catalyzed the employer outreach and engage- ment summarized in this report. Thanks also to our various MAPP college and community partners for sharing your employer contacts and engagement activities, which helped frame this report, including: • South Seattle College, Georgetown campus • North Seattle College • Everett Community College • Shoreline Community College • Renton Technical College • Seattle Jobs Initiative • Apprenticeship and Non-Traditional Employment for Women • Pacific Associates We would like to especially thank Dan Bernard and Pacific Associates for your tireless outreach to employers and encouraging them to complete this survey. This report could not have been completed without you. Written by Business Government Community Connections Design and layout by Noise w/o Sound Photography by Ryan Castoldi TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Background 5 2. Survey Purpose and Methods 6 3. Survey Results 7 3.1 Employer Hiring Needs, Sources, and Priorities 7 3.2 Employer Challenges Filling Jobs 10 3.3 Employer Perceptions of Community and 12 Technical College Graduate Preparedness for Work 3.4 Employer Recommendations for Improving 12 Student Preparedness 3.5 Employer Feedback about Workforce Retention 13 Obstacles, Advancement Requirements and Opportunities 3.6 Employer Partnerships with Community 17 and Technical Colleges 4. Recommendations 17 Attachment A MAPP Employer Survey Respondents 19 “In our area, we are getting more and more manufacturers starting businesses and growing their current ones – boats, airplane parts, health products, fishing poles, food products. -

Planning for Higher Education for Families Resources

PLANNING FOR HIGHER EDUCATION FOR FAMILIES RESOURCE SECTION 1200 FIFTH AVENUE, SUITE 700, SEATTLE, WA 98101 1 [email protected] | CENTSPROGRAM.ORG Table of Contents GETTING A BALLPARK ESTIMATE FOR HIGHER EDUCATION COSTS .......................................................................... 3 COLLEGE NAVIGATOR WEBSITE: http://nces.ed.gov/collegenavigator/ ..................................................... 6 BALANCE SHEET ......................................................................................................................................................... 8 INSTRUCTION GUIDE TO FILL OUT THE BALANCE SHEET: ..................................................................................... 9 BUGET SHEET .......................................................................................................................................................... 10 INSTRUCTION GUIDE TO FILL OUT BUDGET SHEET: ............................................................................................ 12 TRACKING EXPENSES- GENERAL LEDGER ................................................................................................................ 15 SAMPLE GENERAL LEDGER ...................................................................................................................................... 17 SAMPLE SPECIFIC LEDGER ....................................................................................................................................... 19 ENVELOPE METHOD ............................................................................................................................................... -

RAINIER TOWER RAINIER TOWER 1301 Fifth Avenue | Seattle, Washington 98101

RAINIER TOWER RAINIER TOWER 1301 Fifth Avenue | Seattle, Washington 98101 VIEW THE NEW ONLINE TOUR BOOK HERE BUILDING FACTS BUILDING AMENITIES ON-SITE RETAIL » Total Building Size ...................538,000 RSF » New conference room facility » Rainier Square is undergoing » Number of Floors ....................40 » Day-use lockers construction with brand new » Average Floor Plate ................18,700 RSF » Showers retail and building amenities » Year Built .....................................1977 » Parking available in the new tower coming in Q4 2021 » Parking Ratio .............................1 / 1,800 SF » Bike storage available in new tower Click the play buttons for virtual tours Damon McCartney David Greenwood (206) 838-7633 (206) 838-7635 [email protected] [email protected] Fairview Ave N Aloha St Valley St Roy St E Roy St Mercer St Yale Ave N Ave Yale E Mercer St Republican St Republican St Bellevue E Ave Westlake Ave N Ave Westlake Fairview Ave N Ave Fairview Dexter N Ave 9th Ave N 9th Ave Harrison St Thomas St John St Denny Way Westlake Ave 6th Ave Stewart St Battery St WALK SCORE Bell St RAINIER TOWER Blanchard St 99AVG ACROSS ALL 1301 Fifth Avenue | Seattle, Washington 98101 Olive Way METROPOLITAN TRACT BLDGS Lenora St Pine St 1 Virginia St RAINIER 6th Ave TOWER 1 CBD 7 PUGET SOUND 1 5th Ave PLAZA Pike St Lifestyle 6 1. Regal Cinemas 4th Ave 1 2 2. Westlake Park 5 2 1 3. Home Street Bank 3 9 Union St SKINNER 4. 5th Avenue Theater 2 2nd Ave BUILDING 5. U.S. Post Office 7 1 6. Key Bank 4 7 3 6 4 7. -

Registration Document

Believe a French société par actions simplifiée1 (simplified joint-stock company) with share capital of €402,344.21 Registered office: 24 rue Toulouse Lautrec, 75017 Paris Paris Trade and Companies Register (RCS) No. 481 625 853 REGISTRATION DOCUMENT The registration document was approved on 7 May 2021 by the Autorité des Marchés Financiers (AMF) in its capacity as the competent authority under Regulation (EU) 2017/1129. The AMF has approved this document after verifying that the information it contains is complete, consistent and comprehensible. The registration document carries the following approval number: I. 21-018. This approval must not be considered to be a favourable opinion on the issuer described in the registration document. The registration document may be used for the purposes of an offer to the public of securities or admission of securities to trading on a regulated market if it is completed by a securities note and, if applicable, a summary and the supplements thereto. The entire document was approved by the AMF pursuant to Regulation (EU) 2017/1129. It shall be valid until 7 May 2022 and, during this period but no later than at the same time as the securities note and under the conditions of Articles 10 and 23 of Regulation (EU) 2017/1129, it shall be completed by a supplement in the event of new material facts, errors or substantial inaccuracies. DISCLAIMER By accepting this document, you acknowledge, and agree to be bound by, the following statements. This document is a translation of Believe’s document d’enregistrement dated 7 May 2021 (the “Registration Document”). -

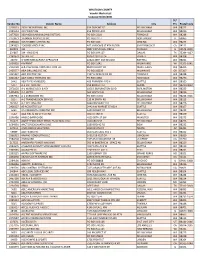

Vendor Number List (PDF)

WHATCOM COUNTY Vendor Master List Updated 06/26/2021 St/ Vendor No. Vendor Name Address City Prv Postal Code 2226513 2020 ENGINEERING INC 814 DUPONT ST BELLINGHAM WA 98225 2231654 24/7 PAINTING 256 PRINCE AVE BELLINGHAM WA 98226 2477603 360 MODULAR BUILDING SYSTEMS PO BOX 3218 FERNDALE WA 98248 2279973 3BRANCH PRODUCTS INC PO BOX 2217 NORTHBOOK IL 60065 2398518 3CS TIMBER CUTTING INC PO BOX 666 DEMING WA 98244 2243823 3DEGREE GROUP INC 407 SANSOME ST 4TH FLOOR SAN FRANCISCO CA 94111 294045 3M 2807 PAYSPHERE CIRCLE CHICAGO IL 60674-0000 234667 3M - XWD3349 PO BOX 844127 DALLAS TX 75284-4127 2161879 3S FIRE LLC 4916 123RD ST SE EVERETT WA 98208 24070 3-WIRE RESTAURANT APPLIANCE 22322 20TH AVE SE #150 BOTHELL WA 98021 1609820 4IMPRINT PO BOX 1641 MILWAUKEE WI 53201-1641 2319728 A & V GENERAL CONSTRUCTION LLC 8630 TILBURY RD MAPLE FALLS WA 98266 2435577 A&A DRILLING SVC INC PO BOX 68239 MILWAUKIE OR 97267 2431437 A&E ELECTRIC INC 2197 ALDERGROVE RD FERNDALE WA 98248 1816247 A&R CABLE THINNING INC PO BOX 4338 NOOKSACK WA 98276 5442 A&V TAPE HANDLERS 405 FAIRVIEW AVE N SEATTLE WA 98109 5477 A-1 GUTTERS INC 250 BOBLETT ST BLAINE WA 98230-4002 2378120 A-1 MOBILE LOCK & KEY 1956 S BURLINGTON BLVD BURLINGTON WA 98233 1405405 A-1 SEPTIC 565 WILTSE LN BELLINGHAM WA 98226 2457944 A-1 SHREDDING INC PO BOX 31366 BELLINGHAM WA 98228-3366 5514 A-1 TRANSMISSION SERVICE 210 W SMITH RD BELLINGHAM WA 98225 162561 A-1 WELDING INC 4000 IRONGATE RD BELLINGHAM WA 98226 2406127 A3 ACOUSTICS LLP 2442 NW MARKET ST #614 SEATTLE WA 98107 6461 AA ANDERSON COMPANY INC -

IBM BUILDING IBM BUILDING 1200 Fifth Avenue | Seattle, Washington 98101

IBM BUILDING IBM BUILDING 1200 Fifth Avenue | Seattle, Washington 98101 BUILDING FACTS BUILDING AMENITIES ON-SITE RETAIL » Total Building Size ...................225,000 RSF » Conference room facility » Mustard Seed Cafe » Number of Floors ....................20 » Shower facilities/ day-use lockers » Union Bank » Average Floor Plate ................12,300 RSF » Secure bike storage » Year Built .....................................1964 » 161 parking stalls » Parking Ratio .............................1 / 1,800 SF » EV charging system » LEED EB Gold Certified Damon McCartney David Greenwood (206) 838-7633 (206) 838-7635 [email protected] [email protected] Fairview Ave N Aloha St Valley St Roy St E Roy St Mercer St Yale Ave N Ave Yale E Mercer St Republican St Republican St Bellevue E Ave Westlake Ave N Ave Westlake Fairview Ave N Ave Fairview Dexter N Ave 9th Ave N 9th Ave Harrison St Thomas St John St Denny Way Westlake Ave 6th Ave Stewart St Battery St WALK SCORE Bell St IBM BUILDING Blanchard St 99AVG ACROSS ALL 1200 Fifth Avenue | Seattle, Washington 98101 Olive Way METROPOLITAN TRACT BLDGS Lenora St Pine St 1 Virginia St RAINIER 6th AveBUILDING 1 CBD 7 PUGET SOUND 1 5th Ave 2 PLAZA Pike St Lifestyle 9 1 1. Regal Cinemas 4th Ave 2 2 2. Westlake Park 6 2 1 3. Home Street Bank 4 10 8 Union St SKINNER 4. 5th Avenue Theater 3 2nd Ave BUILDING 1 5. U.S. Post Office 3 5 10 6. Key Bank 5 8 3 7 4 7. Benaroya Hall 9 8 3 17 16 4 24 8. Seattle Art Museum 15 3 1 4 9. -

Return of Private Foundation 990-PF

Return of Private Foundation OMB No. 1545-0052 Form 990-PF or Section 4947(a)(1) Nonexempt Charitable Trust Department of the Treasury Treated as a Private Foundation Internal Revenue Service Note. The foundation may be able to use a copy of this return to satisfy state reporting requirements. 2011 For calendar year 2011 or tax year beginning , and ending Name of foundation A Employer identification number JOHN S. AND JAMES L. KNIGHT FOUNDATION 65-0464177 Number and street (or P.O. box number if mail is not delivered to street address) Room/suite B Telephone number 200 SOUTH BISCAYNE BLVD 3300 (305)908-2600 City or town, state, and ZIP code C If exemption application is pending, check here~| MIAMI, FL 33131-2349 G Check all that apply: Initial return Initial return of a former public charity D 1. Foreign organizations, check here ~~| Final return Amended return Foreign organizations meeting the 85% test, Address change Name change 2. check here and attach computation ~~~~| H Check type of organization: X Section 501(c)(3) exempt private foundation E If private foundation status was terminated Section 4947(a)(1) nonexempt charitable trust Other taxable private foundation under section 507(b)(1)(A), check here ~| I Fair market value of all assets at end of year J Accounting method: Cash X Accrual F If the foundation is in a 60-month termination (from Part II, col. (c), line 16) Other (specify) under section 507(b)(1)(B), check here ~| | $ 2,033,881,211. (Part I, column (d) must be on cash basis.) Part I Analysis of Revenue and Expenses (a) Revenue and (b) Net investment (c) Adjusted net (d) Disbursements (The total of amounts in columns (b), (c), and (d) may not for charitable purposes necessarily equal the amounts in column (a).) expenses per books income income (cash basis only) 1 Contributions, gifts, grants, etc., received ~~~ N/A 2 Check | X if the foundation is not required to attach Sch. -

Sartorius Stedim Biotech Universal Registration Document 2020 4

Sartorius Stedim Biotech Key Figures All figures are given in millions of € according 2020 Δ in % 20197 2018 2017 2016 to the IFRS, unless otherwise specified Order intake, sales revenue and earnings Order intake 2,381.0 54.3 1,543.5 1,307.3 1,162.3 1,080.8 Sales revenue 1,910.1 32.6 1,440.6 1,212.2 1,081.0 1,051.6 Underlying EBITDA1, 2 604.7 43.5 421.5 342.4 294.9 288.7 Underlying EBITDA1, 2 as % of sales revenue 31.7 2.4 pp 29.3 28.2 27.3 27.5 Net profit after non-controlling interest 357.8 52.6 234.5 208.1 161.1 153.7 Underlying net profit1 after non-controlling interest2 383.8 45.9 263.0 219.3 180.4 176.6 Research and development costs 84.5 6.6 79.2 60.6 53.2 47.5 Financial data per share Earnings per share (in €) 3.88 52.6 2.54 2.26 1.75 1.67 Earnings per share (in €)1, 3 4.16 45.9 2.85 2.38 1.96 1.92 Dividend per share (in €) 0.684 100.0 0.34 0.57 0.46 0.42 Balance sheet Balance sheet total 3,069.3 66.3 1,845.4 1,571.5 1,403.9 1,195.8 Equity 1,482.9 24.7 1,188.9 1,044.9 879.5 763.6 Equity ratio (in %) 48.3 -16.1 pp 64.4 66.5 62.6 63.9 Financials Capital expenditures as % of sales revenue 8.3 -1.1 pp 9.4 14.6 12.6 7.6 Depreciation and amortization 100.9 38.5 72.8 60.9 50.6 44.7 Cash flow from operating activities 416.9 34.4 310.1 227.3 174.7 156.7 Net debt5 527.0 377.2 110.4 125.7 127.1 67.6 Ratio of net debt to underlying EBITDA1, 2, 6 0.8 0.5 pp 0.3 0.4 0.4 0.2 Total number of employees as of December 31 7,566 21.6 6,223 5,637 5,092 4,725 1 Adjusted for extraordinary items 2 For more information on EBITDA, net profit and the underlying presentation, please refer to the Group Business Development chapter and to the Glossary. -

Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the Supreme Court of Washington

NO. ________ IN THE Supreme Court of the United States SEATTLE’S UNION GOSPEL MISSION, Petitioner, v. MATTHEW S. WOODS, Respondent. On Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the Supreme Court of Washington PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI NATHANIEL L. TAYLOR KRISTEN K. WAGGONER ABIGAIL J. ST. HILAIRE JOHN J. BURSCH ELLIS, LI & MCKINSTRY Counsel of Record PLLC RORY T. GRAY 1700 Seventh Ave., ALLIANCE DEFENDING Suite 1810 FREEDOM Seattle, WA 98101 440 First Street, N.W. (206) 682-0565 Suite 600 Washington, D.C. 20001 (616) 450-4235 [email protected] Counsel for Petitioner i QUESTIONS PRESENTED Petitioner Seattle’s Union Gospel Mission is a nonprofit that exists to preach the gospel of Jesus Christ. Mission employees—all of whom must share and live out its beliefs—do so by meeting the needs of the homeless and evangelizing to them. One of the Mission’s many ministries is Open Door Legal Services, a legal clinic that assists those in Mission recovery programs and other vulnerable community members. Respondent Matthew Woods applied for an Open Door position with the stated intent of changing the Mission’s religious beliefs and without satisfying the prerequisites of regular church attendance, a pastor’s recommendation, and an explanation of his relationship with Jesus. Woods sued when the Mission hired a coreligionist instead. A state trial court ruled for the Mission, noting that it is exempt from state non-discrimination law. But the Washington Supreme Court held that exemp- tion violated the state constitution as-applied and declared the Mission’s First Amendment rights limi- ted to the ministerial exception, creating a split with six Courts of Appeals. -

FEDERAL REGISTER VOLUME 35 • NUMBER 242 Tuesday, December 15, 1970 • Washington, D.C

FEDERAL REGISTER VOLUME 35 • NUMBER 242 Tuesday, December 15, 1970 • Washington, D.C. Pages 18945-19004 Agencies in this issue— Agricultural Stabilization and Conservation Service Agriculture Department Atomic Energy Commission Civil Service Commission Commodity Credit Corporation Consumer and Marketing Service Delaware River Basin Commission Environmental Protection Agency Federal Home Loan Bank Board Federal Insurance Administration Federal Maritime Commission Federal Power Commission Federal Reserve System Federal Trade Commission Food and Drug Administration General Services Administration Housing and Urban Development Department Interior Department Internal Revenue Service Interstate Commerce Commission Land Management Bureau Maritime Administration National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration • Post Office Department Public Health Service Small Business Administration Detailed list of Contents appears inside. Latest Edition Guide to Record Retention Requirements [Revised as of January 1, 1970] This useful reference tool is designed they must be kept. Each digest carries to keep businessmen and the general a reference to the full text of the basic public informed concerning the many law or regulation providing for such published requirements in Federal laws retention. and regulations relating to record retention. The booklet’s index, numbering over The 89-page “Guide” contains about 2,200 items, lists for ready reference 1,000 digests which tell the user (1) the categories of persons, companies, what type records must be kept, (2) and products affected by Federal who must keep them, and (3) how long record retention requirements. Price: $1.00 Compiled by Office of the Federal Register, National Archives and Records Service, General Services Administration Order from Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington, D.C.