1996 Report of Gifts (104 Pages)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Unali'yi Lodge

Unali’Yi Lodge 236 Table of Contents Letter for Our Lodge Chief ................................................................................................................................................. 7 Letter from the Editor ......................................................................................................................................................... 8 Local Parks and Camping ...................................................................................................................................... 9 James Island County Park ............................................................................................................................................... 10 Palmetto Island County Park ......................................................................................................................................... 12 Wannamaker County Park ............................................................................................................................................. 13 South Carolina State Parks ................................................................................................................................. 14 Aiken State Park ................................................................................................................................................................. 15 Andrew Jackson State Park ........................................................................................................................................... -

Monck's Corner, Berkeley County, South Carolina

Monck's Corner, Berkeley County, South Carolina by Maxwell Clayton Orvin, 1951 In Memoriam John Wesley Orvin, first Mayor of Moncks Corner, S.C., b. March 13, 1854, d. December 17, 1916.He was the son of John Riley Orvin, a Confederate States Soldier in Co. E., Fifth S.C. Cavalry and Salena Louise Huffman, South Carolina. Transcribed by D. Whitesell for South Carolina Genealogy Trails PREFACE The text of this little book is based on matter compiled for a general history of Berkeley County, and is presented in advance of that unfinished undertaking at the request of several persons interested in the early history of the county seat and its predecessor. Recorded in this volume are facts gleaned from newspaper articles, official documents, and hitherto unpublished data vouched for by persons of undoubted veracity. Newspapers might well be termed the backbone of history, but unfortunately few issues of newspapers published in Berkeley County between 1882 and 1936 can now be found, and there was a dearth of persons interested in ''sending pieces" to the daily papers outside the county. Thus much valuable information about the county at large and the county seat has been lost. A complete file of The Berkeley Democrat since 1936 has been preserved by Editor Herbert Hucks, for which he will undoubtedly receive the blessings of the historically minded. Pursuing the self-imposed task of compiling material for a history of the county, and for this volume, I contacted many people, both by letter and in person, and I sincerely appreciate the encouragement and help given me by practically every one consulted. -

Prints and Their Production; a List of Works in the New York Public Library

N E UC-NRLF PRINTS AND THEIR PRODUCTION A LIST OF WORKS IN THE NEW YORK PUPUBLIC LIBRARY COMPILED BY FRANK WEITENKAMPF, L.H.D. CHIEF, ART AND PRINTS DIVISION NEW YORK PUBLIC LIB-RARY 19 l6 ^4^ NOTE to This list contains the titles of works relating owned the prints and their production, by Reference on Department of The New York Public Library in the Central Build- November 1, 1915. They are Street. ing, at Fifth Avenue and Forty-second Reprinted September 1916 FROM THE Bulletin of The New York Public Library November - December 1915 form p-02 [ix-20-lfl 25o] CONTENTS I. Prints as Art Products PAGE - - Bibliography 1 Individual Artists - - 2>7 - 2 General and Miscellaneous Works Special Processes - - _ . 79 Periodicals and Societies - - - 3 Etching - - - - - - 79 Processes: Line Engraving and Proc- Handbooks (Technical) - - 79 esses IN General - - - 4 History - 81 Regional - ----- 82 Handbooks for the Student and Col- (Subdivided lector ------ 6 by countries.) Stipple 84 Sales and Prices: General Works - 7 Mezzotint - 84 Extra-Illustration - - - - 8 Aquatint 86 Care of Prints ----- 8 Dotted Prints (Maniere Criblee; History (General) . - _ _ 9 Schrotblatter) - - - - 86 Nielli -_--__ H Wood Engraving - - - - 86 Paste Prints ("Teigdrucke") - - 12 Handbooks (Technical) - - 87 Reproductions of Prints - - - 12 History ------ 87 History (Regional) - - - - 13 Block-books ----- 89 (Subdivided by countries; includes History: Regional- - - - 90 Japanese prints.) (Subdivided by countries.) Dictionaries of Artists - - - 26 Lithography ----- 91 Exhibitions (General and Miscel- Handbooks (Technical) - - 91 laneous) 29 History ------ 94 Collections (Public) - - - - 31 Regional - 95 (Subdivided by countries.) (Subdivided by countries.) Collections (Private) - - - - 34 Color Prints ----- 96 II. -

AUDIENCE of the FEAST of the FULL MOON 22 February 2016 – 13 Adar 1 5776 23 February 2016 – 14 Adar 1 5776 24 February 2016 – 15 Adar 1 5776

AUDIENCE OF THE FEAST OF THE FULL MOON 22 February 2016 – 13 Adar 1 5776 23 February 2016 – 14 Adar 1 5776 24 February 2016 – 15 Adar 1 5776 ++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++ As a point of understanding never mentioned before in any Akurian Lessons or Scripts and for those who read these presents: When The Most High, Himself, and anyone else in The Great Presence speaks, there is massive vision for all, without exception, in addition to the voices that there cannot be any misunderstanding of any kind by anybody for any reason. It is never a situation where a select sees one vision and another sees anything else even in the slightest detail. That would be a deliberate deception, and The Most High will not tolerate anything false that is not identified as such in His Presence. ++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++ Encamped and Headquartered in full array at Philun, 216th Realm, 4,881st Abstract, we received Call to present ourselves before The Most High, ALIHA ASUR HIGH, in accordance with standing alert. In presence with fellow Horsemen Immanuel, Horus and Hammerlin and our respective Seconds, I requested all available Seniors or their respective Seconds to attend in escort. We presented ourselves in proper station and I announced our Company to The Most High in Grand Salute as is the procedure. NOTE: Bold-italics indicate emphasis: In the Script of The Most High, by His direction; in any other, emphasis is mine. The Most High spoke: ""Lord King of Israel El Aku ALIHA ASUR HIGH, Son of David, Son of Fire, you that is Named of My Own Name, know that I am pleased with your Company even unto the farthest of them on station in the Great Distances. -

Ballads and Poems Relating to the Burgoyne Campaign. Annotated

: : : to vieit Europe, I desire to state that his great accjuaintancc witti military matters, his long and faithful research into the military histories of modern nations, his correct comprehension of our own late war, and his intimacy with man.v of our leading Generals and Statesmen durinjr the period of its con- tinuance, with his tried and devoted loyalty and patriotism, recommend him as an eminently suitable person to visit foreign countries, to impart as weU as receive proper views upon all such subjects as are connected with his position as a military writer. Such high qualifications, apart from his being a gentleman of family, of fortune, and of refined cultivation, are entitled to the most favorable consideration from all thosH who esteem and admire them. With great respect, A. PLEA8ANTON, Bvt. Major- Gen'l, U.S.A. ExEcunvK Manbioh, I; Wati., D. C, July 13, 1869. f I heartily concur with Gen'l Pleasanton in his high appreciation of the services rendered by Gen'l de Peysteb, upon whom the State of New York has conferred the rank of Brevet Major-General. I commend him to the favorable consideration of those whom he may meet in his present visit to Europe. U. S. GRANT. ExEcunri Mansion, 1 W<ukingtm, D. a, July I3th, 1869. Dear Sir • ) I take pleasure in forwarding to you the enclosed endorsement of the President. Yours Very Truly, Gen. J. Watts db Pktsteb. HORACE PORTER.* •Major of Ordnance, V. 8. A. ; Brtvtt Brigadier-General V. S. A.; A.-de-C. to tke General-in-Chief ; and Private Secretary to the Pretident of the U.S. -

Genres of Financial Capitalism in Gilded Age America

Reading the Market Peter Knight Published by Johns Hopkins University Press Knight, Peter. Reading the Market: Genres of Financial Capitalism in Gilded Age America. Johns Hopkins University Press, 2016. Project MUSE. doi:10.1353/book.47478. https://muse.jhu.edu/. For additional information about this book https://muse.jhu.edu/book/47478 [ Access provided at 28 Sep 2021 08:25 GMT with no institutional affiliation ] This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Reading the Market new studies in american intellectual and cultural history Jeffrey Sklansky, Series Editor Reading the Market Genres of Financial Capitalism in Gilded Age America PETER KNIGHT Johns Hopkins University Press Baltimore Open access edition supported by The University of Manchester Library. © 2016, 2021 Johns Hopkins University Press All rights reserved. Published 2021 Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper Johns Hopkins Paperback edition, 2018 2 4 6 8 9 7 5 3 1 Johns Hopkins University Press 2715 North Charles Street Baltimore, Maryland 21218-4363 www.press.jhu.edu The Library of Congress has cataloged the hardcover edition of this book as folllows: Names: Knight, Peter, 1968– author Title: Reading the market : genres of financial capitalism in gilded age America / Peter Knight. Description: Baltimore : Johns Hopkins University Press, [2016] | Series: New studies in American intellectual and cultural history | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2015047643 | ISBN 9781421420608 (hardcover : alk. paper) | ISBN 9781421420615 (electronic) | ISBN 1421420600 [hardcover : alk. paper) | ISBN 1421420619 (electronic) Subjects: LCSH: Finance—United States—History—19th century | Finance— United States—History—20th century. -

Animals in Central Park, Prospect Park

INDEX Barber Shop Quartet Baseball and Softball Diamonds Birth Announcements (Animals in Central Park, Prospect Park Zoo) Boxing Tournament Bronx Park Plgds,- Boston Road and East l80th Street- Brooklyn Battery Tunnel Plaza Playground Children's Dance Festival (Bronx, Brooklyn, Richmond, Manhattan & Queens!, Concert - Naumburg Orchestra Coney Island Fishing Contest Dyckman House - Closing for refurbishing, painting and general rehabilitation Egg Rolling Contest Flower Show (Greenhouse - Prospect Park) Frank Frisch Field Bleachers Golf Courses St. Harlem River Driveway (repaving section Washington Bridge to Dyckman) Driveway closed) Henry Hudson Parkway (construction of additional access facilities near George Washington Bridge) Kissena Corridor Playground Laurelton Parkway Reconstruction Liberty Poles - City Hall Park Marionette Circus Name Band Dances Osborn Memorial Recreational Facilities St. Nicholas Playground (St. Nicholas Housing Project Manhattan) Tennis Courts Opening Tree Planting &:*.. Van Wyck Expressway and Queens Boulevard « Ward's Island Wollman Memorial (termination of ice and roller skating) DtPARTMEN O F PARKS REGENT 4-1000 ARSENAL, CENTRAL PARK FOR RELEASE IMMEDIATELY Form H-1-10M-508074(53) 114 The seeond of three concerts scheduled this season at the south end of Harlem Meer, 110th Street in Central Park, will be given on Thursday, July SO at 8:30 P. M» Juanito Sanabria and his orchestra will play for this concert. These concerts have again been contributed by an anonymous donor to provide musical entertainment for the residents of the com- munity at the north end of Central Park. Juanito Sanabria*s music for this oonoert will consist of popular Latin-American numbers. As there are no facilities for dancing at Harlem Meer, Mr. -

Palmetto State's Memory, a History of the South Carolina Department of Archives & History 1905-1960

THE PALMETTO STATE’S MEMORY THE PA L M E T TO STATE’S MEMORY i A History of the South Carolina Department of Archives & History, 1905-1960 by Charles H. Lesser A HISTORY OF THE SCDAH, 1905-1960 © 2009 South Carolina Department of Archives & History 8301 Parklane Road Columbia, South Carolina 29223 http://scdah.sc.gov Book design by Tim Belshaw, SCDAH ii THE PALMETTO STATE’S MEMORY TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface ................................................................................................................................................................... v Part I: The Salley Years ................................................................................................................................. 1 Beginnings ......................................................................................................................................................... 1 Confederate and Revolutionary War Records and Documentary Editing in the Salley Years ........... 10 Salley vs. Blease and a Reorganized Commission ..................................................................................... 18 The World War Memorial Building ............................................................................................................ 21 A.S. Salley: A Beleaguered But Proud Man ............................................................................................... 25 Early Skirmishes in a Historical Battle ...................................................................................................... -

Download Attachment

Group Name Address Line 1 Address Line 2 City State Zip ABBEVILLE SCHOOL DISTRICT 60 400 GREENVILLE ST ABBEVILLE SC 296201749 ADJUTANT GENERAL'S OFFICE 1 NATIONAL GUARD RD COLUMBIA SC 292014752 AID TO SUBDIVISIONS-COUNTY AUDITORS & TREASURERS 100 Wade Hampton Buildin Columbia SC 292010000 AIKEN AREA COUNCIL ON AGING 159 MORGAN ST NW AIKEN SC 298013621 AIKEN COUNTY ALCOHOL & DRUG ABUSE COMMISSION 1105 GREGG HWY NW AIKEN SC 298016341 AIKEN COUNTY BOARD OF DISABILITIES 105 LANCASTER STREET AIKEN SC 298013770 AIKEN COUNTY PUBLIC SCHOOLS 1000 BROOKHAVEN DR AIKEN SC 298032109 AIKEN HOUSING AUTHORITY 100 ROGERS TER AIKEN SC 298013435 AIKEN TECHNICAL COLLEGE 2276 JEFFERSON DAVIS HWY GRANITEVILLE SC 298294045 ALLENDALE & BARNWELL COUNTIES DSN BOARD 20 PARK ST BARNWELL SC 298122900 ALLENDALE COUNTY 526 MEMORIAL AVE N ALLENDALE SC 298102712 ALLENDALE COUNTY HOSPITAL PO BOX 218 1787 ALLENDALE FAIRFAX H FAIRFAX SC 298279133 ALLENDALE COUNTY SCHOOL DISTRICT 3249 ALLENDALE FAIRFAX H FAIRFAX SC 298279163 ALLENDALE SOIL & WATER CONSERVATION DISTRICT 398 BARNWELL HIGHWAY ROOM 113 ALLENDALE SC 298102745 ALLIGATOR RURAL WATER & SEWER COMPANY 378 W PINE AVE MC BEE SC 291019229 ALSTON WILKES SOCIETY 3519 MEDICAL DR COLUMBIA SC 292036504 ANDERSON 1&2 CAREER & TECHNOLOGY CENTER 702 BELTON HWY WILLIAMSTON SC 296979520 ANDERSON COUNTY ALTERNATIVE SCHOOL 805 E WHITNER ST ANDERSON SC 296241757 ANDERSON COUNTY DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION SUITE 202 907 NORTH MAIN ST ANDERSON SC 296215513 ANDERSON COUNTY DISABILITY SPECIAL NEEDS BOARD 214 MCGEE RD ANDERSON SC 296252104 -

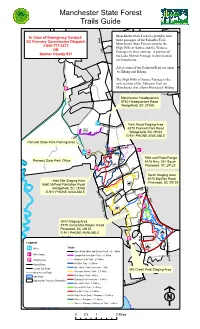

Manchester State Forest Trails Guide

Manchester State Forest Trails Guide d R H Manchester State Forest is proud to host in In Case of Emergency Contact: w G y three passt ages of the Palmetto Trail. n SC Forestry Commission Dispatch r Manchestu er State Forest contains the 1-800-777-3473 B 2 High Hills of Santee and the Wateree 6 OR 1 Passages in their entirety. A portion of Sumter County 911 the Lake Marion Passage is also located d on EMmainl Rchester. S p o ts R All sectionsd of the PalmettoTrail are open to Hiking and Biking. The High Hills of Santee Passage is the only section of the Palmetto Trail on !i Manchester that allows Horseback Riding. Manchester Headquarters 6740 Headquarters Road Wedgefield, SC 29168 !@Hea Park Road Staging Area dquar ad ters Ro 6370 Poinsett Park Road d !G a Wedgefield, SC 29168 o R E-911 PHONE AVAILABLE r Poinsett State Park Parking Area e v i R k Road !i t Par et !© !i ns !@ oi P Rifle and Pistol Range Poinsett State Park Office 5415 Hwy. 261 South d R !G ill Pinewood, SC 29125 s M d !i ma R rist Ch ek Cre rth South Staging Area Ea rs 6070 Big Bay Road Hart Site Staging Area lle u Pinewood, SC 29125 5580 Millford Plantation Road F !È H Wedgefield, SC 29168 w ad d. M o il R y i R ra E-911 PHONE AVAILABLE lf rd o ke ua r a G d L !i 2 w 6 P o D 1 l a n t a t i !i o !È n R d d OHV Staging Area R n i 5775 Camp Mac Boykin Road k y Pinewood, SC 29125 o E-911 PHONE AVAILABLE B !L c a !i M C Legend p o n m n a e Trails C !L !@ Office c t Open Road (Bike and Equine Trail) - 11.1 Miles o r !© Rifle Range R Campbell's Pond Bike Trail - 3.1 Miles -

Tsalagiyi Nvdagi Tribal Minutes of April 17Th, 2021

Tsalagiyi Nvdagi Meeting Minutes April 17th, 2021 Meeting held on Land of Spirits led by UGU Ron Black Eagle Trussell. Present were: UGU Ron Black Eagle Trussell Deputy Chief John Laughing Bear Stephenson Treaty District Chief Jennifer Spirit Wolf Forest Central District Chief Kassa Eagle Wolf Willingham Justice Council Arlie Path Maker Bice Sharon Evening Deer Bice Jack Thunder Hawk Sheridan Brenda Nature Woman Sheridan Laura Kamama Buchmann Elisha Grey Wolf Buchmann Lily Little Hawk Forest Present by Proxie: Northeastern District Chief Ramona Yellow Buffalo Calf Woman TePaske Southern District Chief John Big Sky Garcia At Large District Chief William Crazy Bear Hoff Absent: Northern District Chief Tom Adcox Pacific Northwest Chief Chet McVay Meeting started at 1:00 PM. All were smudged prior to the meeting. Treasurers Report: As of March 31st,2021 Total is $6076.02 A letter from Chief Hoff who is our representative to National Congress of American Indians (NCAI), had attended a virtual meeting by Zoom, on February 21, 2021, and was informed that our Tribe is now listed in the Southwestern Plains Region, having been moved from the Southeastern Region. This is to more accurately reflect our geographic location. The National Conference which was to be held in Alaska, in June, will now be a virtual conference. The new Secretary of the Interior will be a woman of native descent. At Large District Chief William Crazy Bear Hoff is purchasing and paying for the installation of a 12 foot by 20 foot carport to be installed on The Land of Spirits, once the ground is leveled and prepped for the work to be done. -

Presbyterianism : Its Relation to the Negro

^JjJW OF PRINCt PRESBYTERfANISM. ITS RELATION TO THE NEGRO. ILLUSTRATED BY The Berean Presbyterian Church, PHILADELPHIA, WITH SKETCH OF THE CHURCH AND AUTO BIOGRAPHY OF THE AUTHOR MATTHEW ANDERSON, A.M., MEMBER OF THE AMERICAN ACADEMY OF POLITICAL AND SOCIAL SCIENCE, AND THE AMERICAN NEGRO ACADEMY FOR THE PROMOTION OF LETTHRS, ART, LITERATURE AND SCIENCE. WITH INTRODUCTIONS FRANCIS J. GRIMKE, D. D, PASTOR OF THE FIFTEENTH STREET PRESBYTERIAN CHURCH, WASHINGTON, D. C, JOHN B. REEVE, D. D„ PASTOR OK THE CENTRAL PRESBYTERIAN CHURCH, LOMBARD STREET, PHILADELPHIA. PHILADELPHIA, PA. : JOHN McGILL WHITE & CO., 1328 Chestnut Strebt. Copyright, 1897, BY JOHN McGILL WHITE & CO. Thi sunshine Phiss. In compliance with current copyright law, LBS Archival Products produced this replacement volume on paper that meets the AN5I Standard Z39.48-1984 to replace the irreparably deteriorated original. 1992 (So) DEDICATION MY FRIEND TO , JOHN McGILL, WHO FOSTERED AND SUSTAINED THE BEREAN PRESBYTERIAN CHURCH FOR OVER FOURTEEN YEARS, AND TO THE FRIENDS OF THE COLORED PEOPLE GENERALLY, IS THIS BOOK MOST GRATEFULLY AND AFFECTIONATELY DEDICATED BY THE AUTHOR. Philadelphia, Jul}', 1897. INTRODUCTORY NOTE. Presbyterian I have known the pastor of the Berean Church, the Rev. Matthew Anderson, for a number of years. We were in the Theological Seminary at Princeton together, since which time our friendship has deepened with increasing years. From the inception of his work in Philadelphia I have watched his career with the deepest interest, loo much cannot be said in praise of his self-sacrificing and indefatigable efforts in pushing forward the work to which, in the providence of God, he was called shortly after the completion of his Semi- nary course.