Trudeau's World

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Calculus of Interest Canadian Peacekeeping Diplomacy in Cyprus, 1963-1993

Canadian Military History Volume 24 Issue 2 Article 8 2015 A Calculus of Interest Canadian Peacekeeping Diplomacy in Cyprus, 1963-1993 Greg Donaghy Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.wlu.ca/cmh Part of the Military History Commons Recommended Citation Greg Donaghy "A Calculus of Interest Canadian Peacekeeping Diplomacy in Cyprus, 1963-1993." Canadian Military History 24, 2 (2015) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholars Commons @ Laurier. It has been accepted for inclusion in Canadian Military History by an authorized editor of Scholars Commons @ Laurier. For more information, please contact [email protected]. : A Calculus of Interest Canadian Peacekeeping Diplomacy in Cyprus, 1963-1993 A Calculus of Interest Canadian Peacekeeping Diplomacy in Cyprus, 1963-1993 GREG DONAGHY Abstract: Fifty years ago, Canadian peacekeepers landed on the small Mediterranean island of Cyprus, where they stayed for thirty long years. This paper uses declassified cabinet papers and diplomatic records to tackle three key questions about this mission: why did Canadians ever go to distant Cyprus? Why did they stay for so long? And why did they leave when they did? The answers situate Canada’s commitment to Cypress against the country’s broader postwar project to preserve world order in an era marked by the collapse of the European empires and the brutal wars in Algeria and Vietnam. It argues that Canada stayed— through fifty-nine troop rotations, 29,000 troops, and twenty-eight dead— because peacekeeping worked. Admittedly there were critics, including Prime Ministers Pearson, Trudeau, and Mulroney, who complained about the failure of peacemaking in Cyprus itself. -

Debates of the Senate

CANADA Debates of the Senate 2nd SESSION . 39th PARLIAMENT . VOLUME 144 . NUMBER 46 OFFICIAL REPORT (HANSARD) Thursday, April 3, 2008 ^ THE HONOURABLE NOËL A. KINSELLA SPEAKER CONTENTS (Daily index of proceedings appears at back of this issue). Debates and Publications: Chambers Building, Room 943, Tel. 996-0193 Published by the Senate Available from PWGSC ± Publishing and Depository Services, Ottawa, Ontario K1A 0S5. Also available on the Internet: http://www.parl.gc.ca 1045 THE SENATE Thursday, April 3, 2008 The Senate met at 1:30 p.m., the Speaker in the chair. reflect on the importance of clean water, and it is meant, of course, to encourage Canadians to do their part to protect and Prayers. preserve our lakes, rivers, wetlands and aquifers. We have more fresh water than any country in the world, but SENATORS' STATEMENTS we cannot take it for granted. Fresh water is now called blue gold and may soon be the most precious commodity in the world. Our resources will come under increasing demand. JOURNALISTS LOST IN THE LINE OF DUTY We often hear stories about how the United States and other Hon. Joan Fraser: Honourable senators, I rise again this year, nations have designs on our water, but we do not need to go as I do every year, to pay homage to the journalists who, in the abroad to find threats. We need only to look in the mirror. Right preceding year, were killed or died in the line of duty, died now, Canadians are the biggest users and abusers of Canadian covering conflicts or were killed because they were journalists water, and although we must be vigilant about preventing bulk telling truths that someone did not want to be told. -

MARCEL CADIEUX, the DEPARTMENT of EXTERNAL AFFAIRS, and CANADIAN INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS: 1941-1970

MARCEL CADIEUX, the DEPARTMENT of EXTERNAL AFFAIRS, and CANADIAN INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS: 1941-1970 by Brendan Kelly A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History University of Toronto © Copyright by Brendan Kelly 2016 ii Marcel Cadieux, the Department of External Affairs, and Canadian International Relations: 1941-1970 Brendan Kelly Doctor of Philosophy Department of History University of Toronto 2016 Abstract Between 1941 and 1970, Marcel Cadieux (1915-1981) was one of the most important diplomats to serve in the Canadian Department of External Affairs (DEA). A lawyer by trade and Montreal working class by background, Cadieux held most of the important jobs in the department, from personnel officer to legal adviser to under-secretary. Influential as Cadieux’s career was in these years, it has never received a comprehensive treatment, despite the fact that his two most important predecessors as under-secretary, O.D. Skelton and Norman Robertson, have both been the subject of full-length studies. This omission is all the more glaring since an appraisal of Cadieux’s career from 1941 to 1970 sheds new light on the Canadian diplomatic profession, on the DEA, and on some of the defining issues in post-war Canadian international relations, particularly the Canada-Quebec-France triangle of the 1960s. A staunch federalist, Cadieux believed that French Canadians could and should find a place in Ottawa and in the wider world beyond Quebec. This thesis examines Cadieux’s career and argues that it was defined by three key themes: his anti-communism, his French-Canadian nationalism, and his belief in his work as both a diplomat and a civil servant. -

Human Security, Mutual Vulnerability, and Sustainable Development: a Critical View

Human Security, Mutual Vulnerability, and Sustainable Development: A Critical View by Jorge Nef This essay is an attempt to provide a historical and structural frame of reference for the study of human security, from a distinctively “foreign” standpoint.1 More specifically, the essay explores its various meanings, intellectual roots, and antecedents, as well as, the debates and controversies about its significance and its implications for the conduct of global politics and foreign policy. In addition, and more substantively, the aim of the paper is to advance some tentative observations regarding the interface among peace, human rights, and sustainable development in a post–Cold War context. The main thesis in this analysis is that growing interdependence, a main consequence of integration and globalization, creates mutual vulnerability for all nations, groups, and individuals. With the end of World War II, military security and economic development became the parameters of what was then construed as a rigid bipolar world system. The end of the Cold War spearheaded a tendency to celebrate unipolarity and the “end of history”2 as the inevitable result of globalization and the work of market forces. However, this neofunctional utopia came to an abrupt end with the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. In its stead, an all-encompassing and already evolving mutation of the national security doctrine reemerged, centered not on deterrence but on preemption. Its prime manifestation has been the War on Terror. As with the Cold War, but without the constraint of mutual deterrence, security is perceived once again as an endless zero-sum game.3 In this new context, the once unthinkable, yet omnipresent, negative-score game, has become a distinct probability. -

Alternative North Americas: What Canada and The

ALTERNATIVE NORTH AMERICAS What Canada and the United States Can Learn from Each Other David T. Jones ALTERNATIVE NORTH AMERICAS Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars One Woodrow Wilson Plaza 1300 Pennsylvania Avenue NW Washington, D.C. 20004 Copyright © 2014 by David T. Jones All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, scanned, or distributed in any printed or electronic form without permission. Please do not participate in or encourage piracy of copyrighted materials in violation of author’s rights. Published online. ISBN: 978-1-938027-36-9 DEDICATION Once more for Teresa The be and end of it all A Journey of Ten Thousand Years Begins with a Single Day (Forever Tandem) TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction .................................................................................................................1 Chapter 1 Borders—Open Borders and Closing Threats .......................................... 12 Chapter 2 Unsettled Boundaries—That Not Yet Settled Border ................................ 24 Chapter 3 Arctic Sovereignty—Arctic Antics ............................................................. 45 Chapter 4 Immigrants and Refugees .........................................................................54 Chapter 5 Crime and (Lack of) Punishment .............................................................. 78 Chapter 6 Human Rights and Wrongs .................................................................... 102 Chapter 7 Language and Discord .......................................................................... -

Panel Chair Biographies Margaret

Revised on October 14, 2014 Panel Chair Biographies Margaret Boittin is Professor at Osgoode Hall Law School. Previously, she was a Fellow at the Center on Democracy, Development and the Rule of Law at Stanford University. She has a JD from Stanford, and is completing her PhD in Political Science at the University of California, Berkeley. In addition, she holds an MA in Political Science from UC Berkeley and a BA from Yale University. Her PhD dissertation is on the regulation of prostitution in China. She is also conducting research on human trafficking in Nepal, and criminal law policy and local enforcement in the United States. Bilingual in French and English, Boittin is also fluent in Mandarin Chinese, and proficient in Russian and Spanish. Her primary teaching interests are property law, international law, criminal law, state and local government law, Chinese law, comparative law, and empirical methods. Jutta Brunnée is the Interim Dean, Professor of Law and Metcalf Chair in Environmental Law at the University of Toronto, Faculty of Law. Her teaching and research interests are in the areas of Public International Law and International Environmental Law. Her recent work has focused on international law and international relations theory, compliance with international law, the inter-state use of force, domestic application of international law, multilateral environmental agreements, climate change issues and international environmental liability regimes. Professor Brunnée is also the co-author of Legitimacy and Legality in International Law: An Interactional Account (Cambridge University Press, 2010), which was awarded the American Society of International Law’s 2011 Certificate of Merit for preeminent contribution to creative scholarship. -

York University Archives & Special Collections (CTASC) Finding

York University Archives & Special Collections (CTASC) Finding Aid - Richard Jarrell fonds (F0721) Generated by Access to Memory (AtoM) 2.5.3 Printed: December 16, 2019 Language of description: English York University Archives & Special Collections (CTASC) 305 Scott Library, 4700 Keele Street, York University Toronto Ontario Canada M3J 1P3 Telephone: 416-736-5442 Fax: 416-650-8039 Email: [email protected] http://www.library.yorku.ca/ccm/ArchivesSpecialCollections/index.htm https://atom.library.yorku.ca//index.php/richard-jarrell-fonds Richard Jarrell fonds Table of contents Summary information .................................................................................................................................... 10 Administrative history / Biographical sketch ................................................................................................ 10 Scope and content ......................................................................................................................................... 11 Arrangement .................................................................................................................................................. 12 Notes .............................................................................................................................................................. 11 Access points ................................................................................................................................................. 12 Collection holdings ....................................................................................................................................... -

DIPLOMACY, CANADIAN-AMERICAN RELATIONS and ACID RAIN DIPLOMACY, CANADIAN-AMERICAN RELATIONS and the ISSUE of ACID RAIN by NANCY MARY MACKNESON, B.A

DIPLOMACY, CANADIAN-AMERICAN RELATIONS AND ACID RAIN DIPLOMACY, CANADIAN-AMERICAN RELATIONS AND THE ISSUE OF ACID RAIN By NANCY MARY MACKNESON, B.A. (Hons) A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts McMaster University (c) Copyright by Nancy Mary MacKneson, September 1993 MASTER OF ARTS (1993) McMaster University (Political Science) Hamilton, Ontario TITLE: Diplomacy, Canadian-American Relations and the Issue of Acid Rain AUTHOR: Nancy Mary MacKneson, B.A.(Hons) (Trent University) SUPERVISOR: Professor Kim Richard Nossal NUMBER OF PAGES: vi,160 ii ABSlRACf Diplomacy has been an important component in international relations since the earliest of civilizations. As societies evolved, so did diplomacy. In the context of the relationship between Canada and the United States the issue of acid rain resulted in some unusual diplomatic tactics being employed by Canada. This thesis seeks to review the degree of this unusual behaviour and determine whether it is an indication of a shift in the nature of diplomacy in the Canadian-American relationship, or an isolated incident, not likely to be repeated. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMEN1S There are a number of people to whom I am indebted for the successful completion of this thesis. Of particular note is my supervisor, Professor Kim Richard Nossal, for his patience and guidance throughout the many months. In addition, I appreciative of the support and suggestions from Professors Richard Stubbs and George Breckenridge. I also owe a great deal to my parents for granting me the gift of curiosity as well as their constant support as I searched for answers. -

From Ethnic Nationalism to Strategic Multiculturalism

FROM ETHNIC NATIONALISM TO STRATEGIC MULTICULTURALISM: SHIFTING STRATEGIES OF REMEMBRANCE IN THE QUÉBÉCOIS SECESSIONIST MOVEMENT M. LANE BRUNER Abstract The controversy surrounding Jacques Parizeaus M. Lane Bruner is dramatically rejected address on the evening of the Assistant Professor of Québécois referendum on October 30th, 1995, provides an Communication at History opportunity to examine the shifting politics of memory in and Society Division, the Québécois secessionist movement. By tracing the Babson College, Babson historical tensions between French and English Canadians, Park, Massachusetts. the manner in which those tensions were transmuted into language and constitutional law, and how those laws reflect competing articulations of national identity, the Québécois movement is shown to have shifted from an ethnic nationalism based on French Canadien ancestry to a civic nationalism based on strategic multiculturalism. Vol.4 (1997), 3 41 Human beings are situated in both a material political economy and an ideational economy, and there is a symbiotic relationship between those economies (Baudrillard 1981; 1988).1 Contemporary rhetorical theories, premised upon the notion that lan- guage ultimately constitutes and motivates human action, are intimately concerned with the various ways in which the ideational economy, from individual identity to collective identity, is constructed. Following Benedict Andersons (1991) position that collective identities can be productively conceptualised as imagined communities, and building upon that conception by arguing that national identities are politically consequential fictions produced, maintained, and transformed in part by rhetorical processes, I analyse in this essay how the history of political and economic inequality in Canada has contributed to the evolution of public policies and public discourses designed to construct collective national identity in the province of Québec. -

''Six Mois A` Hanoi'': Marcel Cadieux, Canada, and The

BRENDAN KELLY ‘‘Six mois a` Hanoi’’: Marcel Cadieux, Canada, and the International Commission for Supervision and Control in Vietnam, 1954–5 Abstract: Drawing on an unpublished memoir by Marcel Cadieux entitled ‘‘Six mois a` Hanoi,’’ this article offers the first biographical study of a Canadian diplomat to serve on the International Commission for Supervision and Control in Vietnam. It argues that Cadieux’s pioneering experience on that commission during its first months in 1954–5 shaped his pro-American views on the Vietnam War as under- secretary of state for external affairs between 1964 and 1970. It also uses Cadieux’s tenure in Hanoi as a lens through which to explore larger issues of both long-standing and more recent interest to Canadian international historians, including the bureaucratic culture of the Department of External Affairs, Canadian diplomacy’s relationship with the decolonizing countries of the Third World, and the role of race, culture, religion, and anti-communism in the making of Canadian foreign policy. Keywords: Marcel Cadieux, biography, Canada, Vietnam, diplomacy, Interna- tional Commission for Supervision and Control, Department of External Affairs, Cold War, Vietnam War, Third World, decolonization, communism, race, culture, religion Re´sume´ : S’appuyant sur un me´moire ine´dit de Marcel Cadieux intitule´ « Six mois a` Hanoi », l’auteur pre´sente la premie`re e´tude biographique d’un diplomate canadien ayant sie´ge´ a` la Commission internationale pour la surveillance et le controˆle au Vieˆt- Nam. Selon lui, l’expe´rience pionnie`re de Cadieux durant les premiers mois d’existence de cette commission, en 1954-1955, a fac¸onne´ ses opinions proame´ricaines au sujet de la guerre du Vieˆt-Nam alors qu’il e´tait sous-secre´taire d’E´tat aux Affaires exte´rieures, de 1964 a` 1970. -

Bolderboulder 2005 - Bolderboulder 10K - Results Onlineraceresults.Com

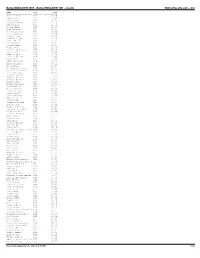

BolderBOULDER 2005 - BolderBOULDER 10K - results OnlineRaceResults.com NAME DIV TIME ---------------------- ------- ----------- Michael Aish M28 30:29 Jesus Solis M21 30:45 Nelson Laux M26 30:58 Kristian Agnew M32 31:10 Art Seimers M32 31:51 Joshua Glaab M22 31:56 Paul DiGrappa M24 32:14 Aaron Carrizales M27 32:23 Greg Augspurger M27 32:26 Colby Wissel M20 32:36 Luke Garringer M22 32:39 John McGuire M18 32:42 Kris Gemmell M27 32:44 Jason Robbie M28 32:47 Jordan Jones M23 32:51 Carl David Kinney M23 32:51 Scott Goff M28 32:55 Adam Bergquist M26 32:59 trent r morrell M35 33:02 Peter Vail M30 33:06 JOHN HONERKAMP M29 33:10 Bucky Schafer M23 33:12 Jason Hill M26 33:15 Avi Bershof Kramer M23 33:17 Seth James DeMoor M19 33:20 Tate Behning M23 33:22 Brandon Jessop M26 33:23 Gregory Winter M26 33:25 Chester G Kurtz M30 33:27 Aaron Clark M18 33:28 Kevin Gallagher M25 33:30 Dan Ferguson M23 33:34 James Johnson M36 33:38 Drew Tonniges M21 33:41 Peter Remien M25 33:45 Lance Denning M43 33:48 Matt Hill M24 33:51 Jason Holt M18 33:54 David Liebowitz M28 33:57 John Peeters M26 34:01 Humberto Zelaya M30 34:05 Craig A. Greenslit M35 34:08 Galen Burrell M25 34:09 Darren De Reuck M40 34:11 Grant Scott M22 34:12 Mike Callor M26 34:14 Ryan Price M27 34:15 Cameron Widoff M35 34:16 John Tribbia M23 34:18 Rob Gilbert M39 34:19 Matthew Douglas Kascak M24 34:21 J.D. -

The Order of Military Merit to Corporal R

Chapter Three The Order Comes to Life: Appointments, Refinements and Change His Excellency has asked me to write to inform you that, with the approval of The Queen, Sovereign of the Order, he has appointed you a Member. Esmond Butler, Secretary General of the Order of Military Merit to Corporal R. L. Mailloux, I 3 December 1972 nlike the Order of Canada, which underwent a significant structural change five years after being established, the changes made to the Order of Military U Merit since 1972 have been largely administrative. Following the Order of Canada structure and general ethos has served the Order of Military Merit well. Other developments, such as the change in insignia worn on undress ribbons, the adoption of a motto for the Order and the creation of the Order of Military Merit paperweight, are examined in Chapter Four. With the ink on the Letters Patent and Constitution of the Order dry, The Queen and Prime Minister having signed in the appropriate places, and the Great Seal affixed thereunto, the Order had come into being, but not to life. In the beginning, the Order consisted of the Sovereign and two members: the Governor General as Chancellor and a Commander of the Order, and the Chief of the Defence Staff as Principal Commander and a similarly newly minted Commander of the Order. The first act of Governor General Roland Michener as Chancellor of the Order was to appoint his Secretary, Esmond Butler, to serve "as a member of the Advisory Committee of the Order." 127 Butler would continue to play a significant role in the early development of the Order, along with future Chief of the Defence Staff General Jacques A.