Hong Kong: the Final Stages

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Monthly Report HK

July 2005 in Hong Kong 01.08.2005 / No 19 A condensed press review prepared by the Consulate General of Switzerland in Hong Kong Introduction Hong Kong has a new Chief of Administration. Yuan revaluation sets stage for boom in HK. Domestic politics Tsang sent condolences to Britain: Chief Executive Donald Tsang Yam-kuen expressed his condolences for victims of the London bombings, saying he was deeply shocked and saddened by the attacks. New chief of administration: Raphael Hui, a veteran civil servant and former Secretary for Financial Services has been appointed as Chief Secretary to the HK government. The new No. 2 of HK is known to be close to the chief executive and to business circles. In his first press interview he said his main tasks would be electoral reforms for the 2007-2008 elections, resolving the West Kowloon controversy and finding new blood for HK politics. Weak attendance at July 1st march: Only 21’000 (barely 4% of 2003 500’000) participated in the traditional protest march prompting Beijing to say that the event had lost its popularity. Democracy and universal suffrage were just two items on the marchers’ growing wish list which also included labour and gay rights. With the resignation of Tung, the shelving of Article 23 and an economy on the rebound most highly contentious issues have faded. Pro-Beijing organizations also staged a morning parade with also about 30’000 people clanging cymbals and singing patriotic songs to mark the handover. One newspaper ironically mentioned that on the same day that more than 200’000 people went to see an exhibit featuring dinosaurs in a shopping mall. -

The Eu Through the Eyes of Asia

THE EU THROUGH THE EYES OF ASIA THE EU THROUGH THE EYES OF ASIA Media, Public and Elite Perceptions in China, Japan, Korea, Singapore and Thailand Editorial Supervisor: Cover Design: Asia-Europe Foundation © Copyright by Asia-Europe Foundation, National Centre for Research on Europe, Ateneo de Manila University and University of Warsaw The views expressed in this publication are strictly those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Asia-Europe Founda- tion, National Centre for Research on Europe, Ateneo de Manila University or University of Warsaw Warsaw 2007 ISBN [...] Printed: Zakład Grficzny Uniwersytet Warszawski, zam. 919/2007 Contentsand, Peter Ryan and A Message from the Asia-Europe Foundation .......................................................7 Acknowledgments .............................................................................................. 9 Prologue: BERTRAND FORT The Strategic Importance of the ESiA Network in Reinforcing Asia-Europe Relations ................................................................................. 11 PART I: INTRODUCTION Chapter 1: MARTIN HOLLAND, PETER RYAN ALOJZY Z. NOWAK NATALIA CHABAN Introduction: The EU through the Eyes of Asia ..........................................23 Chapter 2: NATALIA CHABAN MARTIN HOLLAND Research Methodology ................................................................................ 28 PART II: COUNTRY STUDIES Chapter 3: DAI BINGRAN ZHANG SHUANGQUAN EU Perceptions in China: Emerging Themes from the News Media, Public Opinion, and -

Hong Kong's Endgame and the Rule of Law (Ii): the Battle Over "The People" and the Business Community in the Transition to Chinese Rule

HONG KONG'S ENDGAME AND THE RULE OF LAW (II): THE BATTLE OVER "THE PEOPLE" AND THE BUSINESS COMMUNITY IN THE TRANSITION TO CHINESE RULE JACQUES DELISLE* & KEVIN P. LANE- 1. INTRODUCTION Transitional Hong Kong's endgame formally came to a close with the territory's reversion to Chinese rule on July 1, 1997. How- ever, a legal and institutional order and a "rule of law" for Chi- nese-ruled Hong Kong remain works in progress. They will surely bear the mark of the conflicts that dominated the final years pre- ceding Hong Kong's legal transition from British colony to Chinese Special Administrative Region ("S.A.R."). Those endgame conflicts reflected a struggle among adherents to rival conceptions of a rule of law and a set of laws and institutions that would be adequate and acceptable for Hong Kong. They unfolded in large part through battles over the attitudes and allegiance of "the Hong Kong people" and Hong Kong's business community. Hong Kong's Endgame and the Rule of Law (I): The Struggle over Institutions and Values in the Transition to Chinese Rule ("Endgame I") focused on the first aspect of this story. It examined the political struggle among members of two coherent, but not monolithic, camps, each bound together by a distinct vision of law and sover- t Special Series Reprint: Originally printed in 18 U. Pa. J. Int'l Econ. L. 811 (1997). Assistant Professor, University of Pennsylvania Law School. This Article is the second part of a two-part series. The first part appeared as Hong Kong's End- game and the Rule of Law (I): The Struggle over Institutions and Values in the Transition to Chinese Rule, 18 U. -

Hong Kong British National (Overseas) Visa 4

BRIEFING PAPER Number CBP 8939, 5 May 2021 Hong Kong British By Melanie Gower National (Overseas) visa Esme Kirk-Wade Contents: 1. Background to British National (Overseas) status 2. Calls to extend BN(O) immigration and citizenship rights 3. The new Hong Kong British National (Overseas) visa 4. The BN(O) visa: topical issues www.parliament.uk/commons-library | intranet.parliament.uk/commons-library | [email protected] | @commonslibrary 2 Hong Kong British National (Overseas) visa Contents Summary 3 1. Background to British National (Overseas) status 5 1.1 Acquiring BN(O) status: legislation 5 1.2 Immigration and citizenship rights historically conferred by BN(O) status 6 2. Calls to extend BN(O) immigration and citizenship rights 10 2.1 Until May 2020 10 2.2 Summer 2020: Announcement of a new visa route for BN(O)s 11 2.3 Ten Minute Rule Bill: Hong Kong Bill 2019-21 13 3. The new Hong Kong British National (Overseas) visa 14 3.1 Policy, legislation and guidance 14 3.2 Practical details 14 3.3 More generous terms than other visa categories? 18 4. The BN(O) visa: topical issues 19 4.1 How many people might come to the UK? 19 4.2 Integration support and managing the impact on local areas 19 4.3 The gaps in the UK’s offer 21 4.4 What are other countries doing? 21 Cover page image copyright Attribution: Chinese demonstrators, 2019– 20 Hong Kong protests by Studio Incendo – Wikimedia Commons page. Licensed by Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic (CC BY 2.0) / image cropped. -

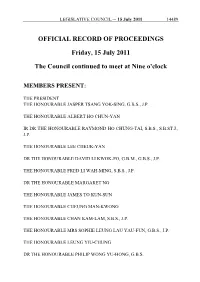

OFFICIAL RECORD of PROCEEDINGS Friday, 15 July

LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ─ 15 July 2011 14489 OFFICIAL RECORD OF PROCEEDINGS Friday, 15 July 2011 The Council continued to meet at Nine o'clock MEMBERS PRESENT: THE PRESIDENT THE HONOURABLE JASPER TSANG YOK-SING, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE ALBERT HO CHUN-YAN IR DR THE HONOURABLE RAYMOND HO CHUNG-TAI, S.B.S., S.B.ST.J., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LEE CHEUK-YAN DR THE HONOURABLE DAVID LI KWOK-PO, G.B.M., G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE FRED LI WAH-MING, S.B.S., J.P. DR THE HONOURABLE MARGARET NG THE HONOURABLE JAMES TO KUN-SUN THE HONOURABLE CHEUNG MAN-KWONG THE HONOURABLE CHAN KAM-LAM, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE MRS SOPHIE LEUNG LAU YAU-FUN, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LEUNG YIU-CHUNG DR THE HONOURABLE PHILIP WONG YU-HONG, G.B.S. 14490 LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ─ 15 July 2011 THE HONOURABLE WONG YUNG-KAN, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LAU KONG-WAH, J.P. THE HONOURABLE LAU WONG-FAT, G.B.M., G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE MIRIAM LAU KIN-YEE, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE EMILY LAU WAI-HING, J.P. THE HONOURABLE ANDREW CHENG KAR-FOO THE HONOURABLE TAM YIU-CHUNG, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LI FUNG-YING, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE TOMMY CHEUNG YU-YAN, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE FREDERICK FUNG KIN-KEE, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE VINCENT FANG KANG, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE WONG KWOK-HING, M.H. -

Minutes Have Been Seen by the Administration)

立法會 Legislative Council LC Paper No. CB(4)88/13-14 (These minutes have been seen by the Administration) Ref : CB4/PL/ITB/1 Panel on Information Technology and Broadcasting Minutes of special meeting held on Tuesday, 25 June 2013, at 8:30 am in Conference Room 1 of the Legislative Council Complex Members present : Hon WONG Yuk-man (Chairman) Hon James TO Kun-sun Hon Emily LAU Wai-hing, JP Hon WONG Ting-kwong, SBS, JP Hon Ronny TONG Ka-wah, SC Hon Cyd HO Sau-lan Hon Mrs Regina IP LAU Suk-yee, GBS, JP Hon Paul TSE Wai-chun, JP Hon LEUNG Kwok-hung Hon Albert CHAN Wai-yip Hon Claudia MO Hon YIU Si-wing Hon MA Fung-kwok, SBS, JP Hon Charles Peter MOK Hon CHAN Chi-chuen Members attending : Hon LEE Cheuk-yan Hon WU Chi-wai, MH Hon Gary FAN Kwok-wai Hon IP Kin-yuen Action - 2 - Members absent : Dr Hon Elizabeth QUAT, JP (Deputy Chairman) Hon Steven HO Chun-yin Hon SIN Chung-kai, SBS, JP Ir Dr Hon LO Wai-kwok, BBS, MH, JP Hon Christopher CHUNG Shu-kun, BBS, MH, JP Public officers : Agenda item I attending Miss Susie HO, JP Permanent Secretary for Commerce and Economic Development (Communications and Technology) Mr Joe WONG, JP Deputy Secretary for Commerce and Economic Development (Communications and Technology) Radio Television Hong Kong Mr Roy TANG, JP Director of Broadcasting Mr TAI Keen-man Deputy Director of Broadcasting (Programmes) Attendance by : Agenda item I invitation Radio Television Hong Kong Programme Staff Union Ms Janet MAK Former Chairperson of Union Ms CHOI Toi-ling Committee Member Civic Party Ms Bonnie LEUNG Exco Member Action -

PDF Full Report

Heightening Sense of Crises over Press Freedom in Hong Kong: Advancing “Shrinkage” 20 Years after Returning to China April 2018 YAMADA Ken-ichi NHK Broadcasting Culture Research Institute Media Research & Studies _____________________________ *This article is based on the same authors’ article Hong Kong no “Hodo no Jiyu” ni Takamaru Kikikan ~Chugoku Henkan kara 20nen de Susumu “Ishuku”~, originally published in the December 2017 issue of “Hoso Kenkyu to Chosa [The NHK Monthly Report on Broadcast Research]”. Full text in Japanese may be accessed at http://www.nhk.or.jp/bunken/research/oversea/pdf/20171201_7.pdf 1 Introduction Twenty years have passed since Hong Kong was returned to China from British rule. At the time of the 1997 reversion, there were concerns that Hong Kong, which has a laissez-faire market economy, would lose its economic vigor once the territory is put under the Chinese Communist Party’s one-party rule. But the Hong Kong economy has achieved generally steady growth while forming closer ties with the mainland. However, new concerns are rising that the “One Country, Two Systems” principle that guarantees Hong Kong a different social system from that of China is wavering and press freedom, which does not exist in the mainland and has been one of the attractions of Hong Kong, is shrinking. On the rankings of press freedom compiled by the international journalists’ group Reporters Without Borders, Hong Kong fell to 73rd place in 2017 from 18th in 2002.1 This article looks at how press freedom has been affected by a series of cases in the Hong Kong media that occurred during these two decades, in line with findings from the author’s weeklong field trip in mid-September 2017. -

Challenger Party List

Appendix List of Challenger Parties Operationalization of Challenger Parties A party is considered a challenger party if in any given year it has not been a member of a central government after 1930. A party is considered a dominant party if in any given year it has been part of a central government after 1930. Only parties with ministers in cabinet are considered to be members of a central government. A party ceases to be a challenger party once it enters central government (in the election immediately preceding entry into office, it is classified as a challenger party). Participation in a national war/crisis cabinets and national unity governments (e.g., Communists in France’s provisional government) does not in itself qualify a party as a dominant party. A dominant party will continue to be considered a dominant party after merging with a challenger party, but a party will be considered a challenger party if it splits from a dominant party. Using this definition, the following parties were challenger parties in Western Europe in the period under investigation (1950–2017). The parties that became dominant parties during the period are indicated with an asterisk. Last election in dataset Country Party Party name (as abbreviation challenger party) Austria ALÖ Alternative List Austria 1983 DU The Independents—Lugner’s List 1999 FPÖ Freedom Party of Austria 1983 * Fritz The Citizens’ Forum Austria 2008 Grüne The Greens—The Green Alternative 2017 LiF Liberal Forum 2008 Martin Hans-Peter Martin’s List 2006 Nein No—Citizens’ Initiative against -

A Case Study of Statutory Minimum Wage in Hong Kong

Lingnan University Digital Commons @ Lingnan University Theses & Dissertations Department of Political Sciences 8-7-2015 Newspaper portrayal and legislative voting process : a case study of statutory minimum wage in Hong Kong Ngai Chiu WONG Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.ln.edu.hk/pol_etd Part of the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Wong, N. C. (2015). Newspaper portrayal and legislative voting process: A case study of statutory minimum wage in Hong Kong (Master's thesis, Lingnan University, Hong Kong). Retrieved from http://commons.ln.edu.hk/pol_etd/14/ This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Political Sciences at Digital Commons @ Lingnan University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Lingnan University. Terms of Use The copyright of this thesis is owned by its author. Any reproduction, adaptation, distribution or dissemination of this thesis without express authorization is strictly prohibited. All rights reserved. NEWSPAPER PORTRAYAL AND LEGISLATIVE VOTING PROCESS: A CASE STUDY OF STATUTORY MINIMUM WAGE IN HONG KONG WONG NGAI CHIU MPHIL LINGNAN UNIVERSITY 2015 NEWSPAPER PORTRAYAL AND LEGISLATIVE VOTING PROCESS: A CASE STUDY OF STATUTORY MINIMUM WAGE IN HONG KONG by WONG Ngai-chiu A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Philosophy in Social Sciences (Political Science) Lingnan University 2015 ABSTRACT Newspaper Portrayal and Legislative Voting Process: A Case Study of Statutory Minimum Wage in Hong Kong by WONG Ngai-chiu Master of Philosophy Statuary Minimum Wage (SMW) has been discussed for 13 years in post-colonial Hong Kong and was finally legislated for in 2010. -

Executive Counsel Limited Political Risk Report No.4: Post 2016 Legislative Council Election Debrief

Executive Counsel Limited Political Risk Report No.4: Post 2016 Legislative Council Election DeBrief The 6th Legislative Council Makeup and Comparison with the 5th Legislative Council Pro-Beijing Pan-Democrats (24,-3) Localists/Self Determination (40,-2) (6,+5) Democratic Alliance for the Democratic Party (7,+1) Youngspiration (2, +2) Betterment and Progress of Hong Civic Party (6, +/-0) Civic Passion (1, +1) Kong (12, -1) Prof. Commons (2, +/-0) Demosisto (1, +1) Business & Professional Alliance (7, Labour Party (1, -3) Independent (2,+2) +/-0) People Power (1, -1) Proletariat Political Institute (0, -1) Federation of Trade Union (5, -1) League of Soc. Dem. (1, +/-0) Liberal Party (4, -1) Neighbourhood and Workers New People Party (3,+1) Services Centre (1,+/-0) New Forum (1) Independents (5, +2) The Federation of HK and Kowloon Association for Democracy and Labour Unions (1) People’s Livelihood (0, -1) Independents (7,+/-0) Neo Democrats (0, -1) Total Vote : 871,016 (40%) Total Vote : 775,578 (35%) Total Vote: 409,025 (19%) Legend: (Total Seats, Change (+/-)) Executive Counsel Limited’s Analysis Key Features • 2,202,283 votes casted, turnout rate 58.58% (+5%) • DAB is still the largest party in the Council (12 seats) , followed by Democratic Party and BPA (both 7 seats). • Average age of legislators decreases from 54 to 46.6 years old; Nathan Law of Demosisto (aged 23) becomes the youngest legislator in Hong Kong history, and will turn 54 in 2047 Localist Candidates From the overall vote gain, localist and pro-self-determination parties proved our comments in Harbour Times* that they are not simply a political quirk. -

Country Fact Sheet, Democratic Republic of the Congo

Issue Papers, Extended Responses and Country Fact Sheets file:///C:/Documents and Settings/brendelt/Desktop/temp rir/Country Fact... Français Home Contact Us Help Search canada.gc.ca Issue Papers, Extended Responses and Country Fact Sheets Home Country Fact Sheet DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF THE CONGO April 2007 Disclaimer This document was prepared by the Research Directorate of the Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada on the basis of publicly available information, analysis and comment. All sources are cited. This document is not, and does not purport to be, either exhaustive with regard to conditions in the country surveyed or conclusive as to the merit of any particular claim to refugee status or asylum. For further information on current developments, please contact the Research Directorate. Table of Contents 1. GENERAL INFORMATION 2. POLITICAL BACKGROUND 3. POLITICAL PARTIES 4. ARMED GROUPS AND OTHER NON-STATE ACTORS 5. FUTURE CONSIDERATIONS ENDNOTES REFERENCES 1. GENERAL INFORMATION Official name Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) Geography The Democratic Republic of the Congo is located in Central Africa. It borders the Central African Republic and Sudan to the north; Rwanda, Burundi, Uganda and Tanzania to the east; Zambia and Angola to the south; and the Republic of the Congo to the northwest. The country has access to the 1 of 26 9/16/2013 4:16 PM Issue Papers, Extended Responses and Country Fact Sheets file:///C:/Documents and Settings/brendelt/Desktop/temp rir/Country Fact... Atlantic Ocean through the mouth of the Congo River in the west. The total area of the DRC is 2,345,410 km². -

12 July 1995 5255 OFFICIAL RECORD of PROCEEDINGS

HONG KONG LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL — 12 July 1995 5255 OFFICIAL RECORD OF PROCEEDINGS Wednesday, 12 July 1995 The Council met at half-past Two o'clock PRESENT THE PRESIDENT THE HONOURABLE SIR JOHN SWAINE, C.B.E., LL.D., Q.C., J.P. THE CHIEF SECRETARY THE HONOURABLE MRS ANSON CHAN, C.B.E., J.P. THE FINANCIAL SECRETARY THE HONOURABLE SIR NATHANIEL WILLIAM HAMISH MACLEOD, K.B.E., J.P. THE ATTORNEY GENERAL THE HONOURABLE JEREMY FELL MATHEWS, C.M.G., J.P. THE HONOURABLE ALLEN LEE PENG-FEI, C.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE MRS SELINA CHOW LIANG SHUK-YEE, O.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE HUI YIN-FAT, O.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE MARTIN LEE CHU-MING, Q.C., J.P. DR THE HONOURABLE DAVID LI KWOK-PO, O.B.E., LL.D., J.P. THE HONOURABLE NGAI SHIU-KIT, O.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE PANG CHUN-HOI, M.B.E. THE HONOURABLE SZETO WAH THE HONOURABLE TAM YIU-CHUNG THE HONOURABLE ANDREW WONG WANG-FAT, O.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LAU WONG-FAT, O.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE EDWARD HO SING-TIN, O.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE RONALD JOSEPH ARCULLI, O.B.E., J.P. 5256 HONG KONG LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL — 12 July 1995 THE HONOURABLE MARTIN GILBERT BARROW, O.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE MRS PEGGY LAM, O.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE MRS MIRIAM LAU KIN-YEE, O.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LAU WAH-SUM, O.B.E., J.P.