Group Captain Percy Charles “Pick” Pickard DSO**, DFC 1915 - 1944

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spring 2017 Issue-All

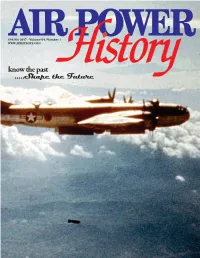

SPRING 2017 - Volume 64, Number 1 WWW.AFHISTORY.ORG know the past .....Shape the Future The Air Force Historical Foundation Founded on May 27, 1953 by Gen Carl A. “Tooey” Spaatz MEMBERSHIP BENEFITS and other air power pioneers, the Air Force Historical All members receive our exciting and informative Foundation (AFHF) is a nonprofi t tax exempt organization. Air Power History Journal, either electronically or It is dedicated to the preservation, perpetuation and on paper, covering: all aspects of aerospace history appropriate publication of the history and traditions of American aviation, with emphasis on the U.S. Air Force, its • Chronicles the great campaigns and predecessor organizations, and the men and women whose the great leaders lives and dreams were devoted to fl ight. The Foundation • Eyewitness accounts and historical articles serves all components of the United States Air Force— Active, Reserve and Air National Guard. • In depth resources to museums and activities, to keep members connected to the latest and AFHF strives to make available to the public and greatest events. today’s government planners and decision makers information that is relevant and informative about Preserve the legacy, stay connected: all aspects of air and space power. By doing so, the • Membership helps preserve the legacy of current Foundation hopes to assure the nation profi ts from past and future US air force personnel. experiences as it helps keep the U.S. Air Force the most modern and effective military force in the world. • Provides reliable and accurate accounts of historical events. The Foundation’s four primary activities include a quarterly journal Air Power History, a book program, a • Establish connections between generations. -

A M D G Beaumont Union Review Summer 2020

A M D G BEAUMONT UNION REVIEW SUMMER 2020 "And I said to the man who stood at the gate of the year: ―Give me a light that I may tread safely into the unknown.‖ Well, we didn‘t see this one coming. Having written in the last REVIEW about ―a year like no other‖ which concludes in this Edition, no one thought we would be living through another. Over 90% of the BU have been confined and we have seen the cancellation of The HCPT and BOFs Pilgrimage to Lourdes, The Verdun Battlefield Tour, The BUGS Meeting at Westerham and Ant Stevens much anticipated Musical ―Streetwise‖: Now rescheduled for 24-29 May 2021. Much quoted at the moment ―We will meet again, Don‘t know where, Don‘t know when but I know we will meet again some sunny day: - Actually it looks like a cloudy day in the Autumn if we are lucky! I was amazed by the response to my Easter Message: I don‘t know whether it could be described as an ―Urbi et Orbi‖ moment but it did bring a huge response from OBs worldwide. One such from Patrick Agnew which I share with you:- ―Indeed. We have taken a lot for granted, during our years; much to be grateful for. Humanity is vulnerable to many things, some much worse than seen now. Globalization has it‘s many drawbacks, as well. Our precious little planet, in such perfect evolved balance, for so many eons, is also threatened by the economic ―progress‖ of mankind, whose numbers compound upwards and ravage resources, and are poisoning them. -

Number 617 Squadron After the Dams Raid by Robert Owen

Number 617 Squadron after the Dams Raid by Robert Owen In May 1943 Number 617 Squadron of Bomber Command, the Royal Air Force, succeeded in breaching two of Germany’s great dams. A few months after this success the Squadron moved from its airfield at Scampton in Lincolnshire to a new base: Coningsby, in the same county. The Squadron had a new commander, Sqn Ldr George Holden, and was re-equipped with Lancasters that had been adapted to carry the latest and heaviest weapon in Bomber Command’s arsenal, a 12,000 lb blast bomb that looked rather like three large dustbins bolted together. On the night of 15/16 September 1943, 8 aircraft carrying this weapon were despatched to make a low level attack against an embanked section of the Dortmund – Ems Canal. The canal was an important link in Germany’s internal transport network. A combination of bad weather and heavy defences took their toll. Five of the eight aircraft, including that of the Squadron Commander, failed to return.The canal was undamaged. Sir Arthur Harris, Commander in Chief of Bomber Command, was faced with the choice of what to do with the depleted Squadron. He decided to re-build it for special duties. Harris knew that Barnes Wallis, inventor of the bouncing mine that had broken the dams back in May, was developing a new bomb. Wallis’s latest weapon was designed to penetrate deep into the ground before exploding, and so to cause an earthquake effect that would destroy the most substantial of structures. Although this was not yet ready, it would need to be dropped from high level with great accuracy. -

The Thunder Anthony Beaucamp-Protor Farewell Uncle

Military Despatches Vol 49 July 2021 The Aces The top fighter pilots of World War I Farewell Uncle Syd We pay tribute to Uncle Syd Ireland, the last South African signaller of World War II The Thunder Poland‘s Special Forces unit, JW GROM Anthony Beaucamp-Protor South Africa’s leading fighter ace of World War I and recipient of the Victoria Cross For the military enthusiast Military Despatches CONTENTS YouTube Channel July 2021 Page 14 Click on any video below to view Army Speak 101 The SADF had their own language. A mixture of Eng- lish, Afrikaans, slang and tech- no-speak that few outside the military could hope to under- stand. Paratrooper Wings Most armies around the world Elite Military Quiz also had their own slang terms. Units Quiz Most military paratroopers In this video we look at some Most military forces have an are awarded their jump wings of them. elite unit or regiment or a spe- Special Forces - JW GROM after they have qualified. cial forces component. In this quiz we show you 15 In this quiz we show you 15 different wings and you tell us and you tell us who they are and 30 where they are from. where they are from. Features 18 Battle of Britain - a few facts 6 The Battle of Britain lasted Top Ten WWI Fighter Pilots from 10 July – 31 October 1940 The Top Ten fighter aces of and was the first major mili- New videos World War I. tary campaign in history to be each week fought entirely in the air. -

Aafffttteeerrr Tthhheee Bbaaattttttlllee

AAFFTTEERR TTHHEE BBAATTTTLLEE THEN NOW COMING SOON The Battles for Cassino encompassed one of the few truly international conflicts of the Second World War. A strategic town on the road to Rome, the fighting lasted four months and cost the lives of more than 14,000 men from eight nations. Between January and May 1944, forces from Britain, Canada, France, India, New Zealand, Poland and the United States, fought a resolute German army in a series of battles in which the advantage swung back and forth, from one side to the other. From fire-fights in the mountains to tank attacks in the valley; from river crossings to street fighting, the four battles of Cassino encompass a series of individual operations unique in the history of the Second World War. Authors Jeff Plowman and Perry Rowe have spent several years studying the conflict together and walking the battlefield to take the hundreds of comparison photographs which are the raison d’etre of all After the Battle publications. Photographs have been selected from archives and private collections around the world to present a balanced view, combined with maps, orders of battle, citations and detailed captions. The Cassino battles, epitomised by the controversial bombing of the monastery which towers menacingly over the battlefield, stand at the centre of the Italian campaign. The dogged defence by a 100,000 men of the German XIV. Panzerkorps under General Frido von Senger und Etterlin, facing a greater multi-national force, was only routed in the end by a gallant French flanking manoeuvre, with the Poles marking the final victory by hoisting their national flag over the ruins of the Monastery. -

Issues 60 to 69

“Bristol” BLENHEIM The Journal of the Blenheim Society List of Contents Abbreviations for rank: Other Ranks Notes & Search Words: G/Cpt Group Captain LAC Leading Aircraftsman Main categories in this column are: W/Cdr Wing Commander AC1 Aircraftsman 1st Class People Places Sq/Ldr Squadron Leader AC2 Aircraftsman 2nd Class Squadrons Dates F/Lt Flight Lieutenant Bristol Blenheim (BB) Serial numbers F/O Flying Officer Other abbreviations P/O Pilot Officer CO Commanding Officer For ease of search & consistency: NCOs Non Commissioned Officers Wop/AG Wireless operator/Air gunner Dates are written as: dd/mm/yyyy W/O Warrant Officer Obs Observer (navigator) or (if month only): mm/yyyy F/Sgt Flight Sergeant OTU Operation Training Unit Squadrons listed as: 18Sq, 21Sq, etc Sgt Sergeant Kia Killed in Action Ref to journals: Issue 56, page 4 = 56/4 Cpl Corporal Other less frequently used abbreviations are listed at end Contact details (email, phone, address) given in the journal are not shown here. To respond to any requests for information please use the email address at the bottom of the website Issue 69: March 2011 Topic Page Type Title Author Notes & Search Words 1 Report An Easter Message Graham Progress on Mk I BB slow dues to lack of from our President Warner funds. Try to increase sale of Draw tickets. Stall sales by Ron Scott et al doing well. 1 Report Chairman’s Andrew £26,000 raised in 2010 (& £120,000 in last Comments Pierce 10 years) for Blenheim. Current work on engines expensive. Concern that cuts in RAF could affect Air Shows; last displays by a Harrier and Nimrod. -

© Osprey Publishing • © Osprey Publishing • HITLER’S EAGLES

www.ospreypublishing.com © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com HITLER’S EAGLES THE LUFTWAFFE 1933–45 Chris McNab © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com CONTENTS Introduction 6 The Rise and Fall of the Luftwaffe 10 Luftwaffe – Organization and Manpower 56 Bombers – Strategic Reach 120 Fighters – Sky Warriors 174 Ground Attack – Strike from Above 238 Sea Eagles – Maritime Operations 292 Ground Forces – Eagles on the Land 340 Conclusion 382 Further Reading 387 Index 390 © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com INTRODUCTION A force of Heinkel He 111s near their target over England during the summer of 1940. Once deprived of their Bf 109 escorts, the German bombers were acutely vulnerable to the predations of British Spitfires and Hurricanes. © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com he story of the German Luftwaffe (Air Force) has been an abiding focus of military Thistorians since the end of World War II in 1945. It is not difficult to see why. Like many aspects of the German war machine, the Luftwaffe was a crowning achievement of the German rearmament programme. During the 1920s and early 1930s, the air force was a shadowy organization, operating furtively under the tight restrictions on military development imposed by the Versailles Treaty. Yet through foreign-based aircraft design agencies, civilian air transport and nationalistic gliding clubs, the seeds of a future air force were nevertheless kept alive and growing in Hitler’s new Germany, and would eventually emerge in the formation of the Luftwaffe itself in 1935. The nascent Luftwaffe thereafter grew rapidly, its ranks of both men and aircraft swelling under the ambition of its commander-in-chief, Hermann Göring. -

Dispersal 02/2013

2nd TACTICAL AIR FORCE MEDIUM BOMBERS ASSOCIATION Incorporating 88, 98, 107, 180, 226, 305, 320, & 342 Squadrons 137, 138 & 139 Wings, 2 Group RAF MBA Canada Executive Chairman/Newsletter Editor David Poissant 242 Harrowsmith Drive, Mississauga, ON L5R 1R2 Telephone: 905-568-0184 E-mail: [email protected] Secretary/Treasurer Susan MacKenzie 406 Devine Street, Sarnia, ON N7T 1V5 Telephone: 519-332-2765 E-mail: [email protected] Western Representative Ken Wright (Pilot • 180 Sqn) 2714 Keighley Road, Nanaimo, BC V9T 5X8 Telephone: 250-756-3138 E-mail: [email protected] Eastern Representative Darrell Bing 75 Baroness Close, Hammond Plains, NS B4B 0B4 Telephone: 902-463-7419 E-mail: [email protected] MBA United Kingdom Executive Chairman/Liason Leonard Clifford (Wireless Op/Air Gunner • 88 Sqn) Fayre Oaks, Broad Lane, Tamworth-in-Arden, Warwickshire B94 5HX Telephone: 01564 742537 Secretary/Archivist Russell Legross 15 Holland Park Drive, Hedworth Estate, Jarrow, Tyne & Wear NE32 4LL Telephone: 0191 4569840 E-mail: [email protected] Treasurer Frank Perriam 3a Farm Way, Worcester Park, Surrey KT4 8RU Telephone: 07587 366371 E-mail: [email protected] Registrar John D. McDonald 35 Mansted Gardens, Chadwell Heath, Romford, Essex RM6 4ED Telephone: 020 8590 2524 E-mail: [email protected] Newsletter Editor Peter Jenner 13 Squirrel Close, Sandhurst, Berks GU47 9Dl Telephone: 01252 877031 E-mail: [email protected] MBA Executive - Australia Secretary Tricia Williams PO Box 16, Ormond, Victoria, Australia 3204 Telephone: 03 9578 5390 E-mail: [email protected] DISPERSALS is published February ● May ● August ● November On our cover: B-25 MkIIs taxi along perimeter track at B58/Melsbroek before taking off on a daylight raid on the bridge at Venlo, Holland. -

IN THIS ISSUE PM Makes Promises to Veterans, Immigrants

Volume - 2 Edition 37 Week Ending September 16, 2008 IN THIS ISSUE PM makes promises to · PM makes promises to veterans, immigrants veterans, immigrants · Callendar Legion Ships Books To Troops · Yacht races honour veterans · Losing he who made their life possible · Canada’s new medal honouring post-911 veterans a betrayal, says vet · Veteran Appreciation Day in Brampton · Hilda Dietrich Memorial · Remembering the Battle of Britain, July 10 - September 6 1940 · What a real winner looks like · Election ad is a disservice to those who have served · Military Service Recognition Book Project · Comrade Leonard George Amos-Legion Service Prime Minister Stephen Harper greets · Forces come together to remember air veterans supporters at the Conservative rally at John · Al Lilly, Don McClure lauded as part of ceremonies commememorating 68th Paul II Polish Cultural Centre during an anniversary of Battle of Britain election stop in Mississauga. · North Bay Veterans mark Battle of Britain Credit: Nikki Wesley · Letter-writing campaign big hit with soldier September 9, 2008 09:37 PM - The Federal Conservative campaign bus rolled into Mississauga tonight, stopping off at the John Paul II Polish Cultural Centre. In a speech aimed at new Canadians, Prime Minister Stephen Harper announced he would be putting the issue of recognizing foreign professional credentials on the agenda for his next meeting with provincial premiers, if re-elected. "Looking ahead, we know we need to do more to recognize the work and educational experience of immigrants in the Canadian job market," Harper told a packed Centre. "It is essential for the future growth of this country." Harper also announced that veterans who fought for Commonwealth and allied forces during World War II - and who have been living in Canada for more than 10 years - would be entitled to receive a Veterans Allowance. -

“To What Extent Could Operation Carthage Be Considered a Successful Mission?”

International School of Helsingborg Christian Jorgensen. Grade 11 Historical investigation May 8th 2006 Total amount of words: 2000 “To what extent could Operation Carthage be considered a successful mission?” 1 Table of contents A. Plan of the investigation…………………………………………………………………3 B. Summary of evidence……………………………………………………………………4 C. Evaluation of sources……………………………………………………………………7 D. Analysis………………………………………………………………………………….8 E. Conclusion and evaluation………………………………………………………………11 F. Bibliography…… …………….………………………………………………………..12 2 Plan of the investigation This historical investigation intends to answer the question: To what extent could Operation Carthage be considered a successful mission? The objective of the investigation is to make a historiographical assessment of the air operation carried out by the RAF in Copenhagen on 21. March 1945. It will evaluate the background and purpose of the mission, the achievements and effectiveness of the attack and the collateral damage inflicted upon civilians. A conclusion will be given contrasting the criteria of military success with that the demographic impact of the mission. For this purpose both primary and contemporary secondary sources will be consulted and assessed. 3 Summary of evidence Before the operation In March 1944 the Gestapo moved its Danish headquarter to the Shell House, in Copenhagen. During the fall of 1944 and the winter of 1945 the Gestapo led an aggressive policy to break down the Danish Liberation Council and great parts of the resistance movement1. The Danes pledged help to Britain, resulting in air attacks leading to the destruction of the Gestapo offices in Aalborg. The first plans for Operation Carthage, the code for an air attack on the Shell House in Copenhagen, were forwarded to England in December 19442, yet no answer came back. -

Astons Auctioneers & Valuers

Astons Auctioneers & Valuers Baylies Hall Tower Street Dudley Film & Music Memorabilia Auction West Midlands DY1 1NB Started 30 Jun 2016 12:00 BST United Kingdom Lot Description Star Wars cinema banners. Star Wars Episode II Attack of the Clones original cinema banners including Bobba Fett, Anakin Skywalker 1 etc., measuring 69 x 47 inch each in very good condition with one vertical fold line.(4) Alfred Hitchcock "The Man Who Knew Too Much / The Trouble with Harry" US insert combo film poster re-release from 1963 (14" x 36") 2 framed with UV protective glass. "Reach for the Sky" 1956 cinema advert in full colour (11" x 14") featuring the true story of Douglas Bader and starring Kenneth Moore. 3 Double-sided title card with synopsis to reverse. Printed in Great Britain, Framed. 4 "The Ladykillers" 1955 framed title card with synopsis to reverse. Framing allows viewing of front and back of title card. James Bond "Casino Royale" 1967 Original three sheet film poster (78" x 42") with psychedelic Bond girl artwork. Art by Robert 5 McGinnis. Linenbacked "The Lady Vanishes" Alfred Hitchcock original Spanish film poster (29" x 40"). Great image of Hitchcock with the train & car action 6 scenes. Printed by Jayaraman Litho Press, Madras-4. Linen backed. Alfred Hitchocks "Rear Window" Early 60s re-release Indian film poster (30 " x 40") with great images of James Stewart with his 7 binoculars together with Grace Kelly. Linen backed. "King Kong" starring Fay Wray Italian 2 Foglio film poster (39" x 55") with printed signature of the great Italian artist Renato Casaro RR 8 1973 Linen backed. -

Issues 50 to 59

“Bristol” BLENHEIM The Journal of the Blenheim Society List of Contents Abbreviations for rank: Other Ranks Notes & Search Words: G/Cpt Group Captain LAC Leading Aircraftsman Main categories in this column are: W/Cdr Wing Commander AC1 Aircraftsman 1st Class People Places Sq/Ldr Squadron Leader AC2 Aircraftsman 2nd Class Squadrons Dates F/Lt Flight Lieutenant Bristol Blenheim (BB) Serial numbers F/O Flying Officer Other abbreviations P/O Pilot Officer CO Commanding Officer For ease of search & consistency: NCOs Non Commissioned Officers Wop/AG Wireless operator/Air gunner Dates are written as: dd/mm/yyyy W/O Warrant Officer Obs Observer (navigator) Squadrons listed as: 18Sq, 21Sq, etc F/Sgt Flight Sergeant OTU Operation Training Unit Ref to journals: Issue 56, page 4 = 56/4 Sgt Sergeant Kia Killed in Action Cpl Corporal Other less frequently used abbreviations are listed at end Issue 59: July 2007 – Celebrating 20 years of the Blenheim Society 1987 to 2007 Topic Page Type Title Author Notes & Search Words 1 Poem Epitaph for the Denis Poem written in 1942 “Someone said that it Blenheim Boys Ager couldn’t be done …” Blenheim 2 Data President and Names and contact details of 7 society Society Committee ‘officials’ and 4 committee members 2 Report President’s Message Graham Society membership growing, merchandise Warner selling well, repair fund increasing, free copy of ‘Aeroplane’ (Oct ’05) included + database of surviving BBs. Thanks to all! 3 Report Chairman’s Andrew 1 in 5 of Society is a ‘founder’ member (flew Comments Pierce in BBs) & ‘treated’ to events this year. Editorial 3 Report Editorial Ian Carter Bumper 24-page anniversary issue.