John Paul Jones

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Richatd Henry Lee 0Az-1Ts4l Although He Is Not Considered the Father of Our Country, Richard Henry Lee in Many Respects Was a Chief Architect of It

rl Name Class Date , BTocRAPHY Acrtvrry 2 Richatd Henry Lee 0az-1ts4l Although he is not considered the father of our country, Richard Henry Lee in many respects was a chief architect of it. As a member of the Continental Congress, Lee introduced a resolution stating that "These United Colonies are, and of right ought to be, free and independent States." Lee's resolution led the Congress to commission the Declaration of Independence and forever shaped U.S. history. Lee was born to a wealthy family in Virginia and educated at one of the finest schools in England. Following his return to America, Lee served as a justice of the peace for Westmoreland County, Virginia, in 1757. The following year, he entered Virginia's House of Burgesses. Richard Henry Lee For much of that time, however, Lee was a quiet and almost indifferent member of political connections with Britain be Virginia's state legislature. That changed "totaIIy dissolved." The second called in 1765, when Lee joined Patrick Henry for creating ties with foreign countries. in a spirited debate opposing the Stamp The third resolution called for forming a c Act. Lee also spoke out against the confederation of American colonies. John .o c Townshend Acts and worked establish o to Adams, a deiegate from Massachusetts, o- E committees of correspondence that seconded Lee's resolution. A Declaration o U supported cooperation between American of Independence was quickly drafted. =3 colonies. 6 Loyalty to Uirginia An Active Patriot Despite his support for the o colonies' F When tensions with Britain increased, separation from Britain, Lee cautioned ! o the colonies organized the Continental against a strong national government. -

Patrick Henry

LIBERTY UNIVERSITY PATRICK HENRY: THE SIGNIFICANCE OF HARMONIZED RELIGIOUS TENSIONS A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE HISTORY DEPARTMENT IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN HISTORY BY KATIE MARGUERITE KITCHENS LYNCHBURG, VIRGINIA APRIL 1, 2010 Patrick Henry: The Significance of Harmonized Religious Tensions By Katie Marguerite Kitchens, MA Liberty University, 2010 SUPERVISOR: Samuel Smith This study explores the complex religious influences shaping Patrick Henry’s belief system. It is common knowledge that he was an Anglican, yet friendly and cooperative with Virginia Presbyterians. However, historians have yet to go beyond those general categories to the specific strains of Presbyterianism and Anglicanism which Henry uniquely harmonized into a unified belief system. Henry displayed a moderate, Latitudinarian, type of Anglicanism. Unlike many other Founders, his experiences with a specific strain of Presbyterianism confirmed and cooperated with these Anglican commitments. His Presbyterian influences could also be described as moderate, and latitudinarian in a more general sense. These religious strains worked to build a distinct religious outlook characterized by a respect for legitimate authority, whether civil, social, or religious. This study goes further to show the relevance of this distinct religious outlook for understanding Henry’s political stances. Henry’s sometimes seemingly erratic political principles cannot be understood in isolation from the wider context of his religious background. Uniquely harmonized -

Foundation Document, George Rogers

NATIONAL PARK SERVICE • U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Foundation Document George Rogers Clark National Historical Park Indiana July 2014 Foundation Document George Rogers Clark National Historical Park and Related Heritage Sites in Vincennes, Indiana S O I Lincoln Memorial Bridge N R I L L I E I V Chestnut Street R H A S Site of A B VINCENNES Buffalo Trace W UNIVERSITY Short Street Ford et GEORGE ROGERS CLARK e r t S Grouseland NATIONAL HISTORICAL PARK t A 4 Home of William Henry Harrison N ot A levard c I Bou S Parke Stree t Francis Vigo Statue N D rtson I Culbe Elihu Stout Print Shop Indiana Territory Capitol 5 Vincennes State Memorial t e Historic Sites ue n Building North 1st Street re t e e v S et u n A Parking 3 Old French House tre s eh ve s S li A Cemetery m n po o e 2 Old State Bank cu Visitor Center s g e ri T e ana l State Historic Site i ar H Col Ind 7 t To t South 2nd Street e e Fort Knox II State Historic Site ee r Father Pierre Gibault Statue r treet t t North 3rd S 1 S and 8 Ouabache (Wabash) Trails Park Old Cathedral Complex Ma (turn left on Niblack, then right on Oliphant, t r Se Pe then left on Fort Knox Road) i B low S n B Bus un m il rr r Ha o N Du Barnett Street Church Street i Vigo S y t na W adway S s i in c tre er North St 4t boi h Street h r y o o S Street r n l e et s eet a t Stree Stre t e re s Stree r To 41 south Stre et reet To 6 t t reet t S et et Sugar Loaf Prehistoric t by St t t et o North 5th Stre Indian Mound Sc Shel (turn left on Washington Avenue, then right on Wabash Avenue) North 0 0.1 0.2 Kilometer -

Joseph Saunders 1713–1792

Chapter 2 JOSEPH4 SAUNDERS 1713-1792 1 Chapter Two Revised January 2021 JOSEPH4 SAUNDERS 1713–1792 From Great Britain to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 1708 England 3 Joseph Saunders = Susannah Child . c.1685 4 Mary Sarah JOSEPH SAUNDERS Timothy John Richard 1709– 1711– 1713–1792 1714– 1716– 1719– m. Hannah Reeve OSEPH4 SAUNDERS was born on the 8th day of January 1712/1713 at Farnham Royal, County of Bucks, Great Britain in the reign of Queen Anne (1702–1714). The records of the Society of Friends in England, Buckinghamshire Quaker Records, Upperside Meeting, indicate that Joseph was the third child and eldest son of Joseph3 Saunders, wheelwright, who on 17th June 1708 had married Susannah Child, the daughter of a prominent Quaker family. He had three brothers and two sisters. Register of Births belonging to the Monthly Meeting of Upperside, Buckinghamshire from 1656–1775, TNA Ref. RG6 / Piece 1406 / Folio 23: Missing from the account of Joseph4 Saunders is information on his early life in Britain: the years leading up to 1732 when he left for America. He was obviously well educated with impressive handwriting skills and had a head for numbers. Following Quaker custom, his father, who was a wheelwright, would have apprenticed young Joseph when he was about fourteen to a respectable Quaker merchant. When he arrived in America at the age of twenty he knew how to go about setting himself up in business and quickly became a successful merchant. The Town Crier 2 Chapter 2 JOSEPH4 SAUNDERS 1713-1792 The Quakers Some information on the Quakers, their origins and beliefs will help the reader understand the kind of society in which Joseph was reared and dwelt. -

FISHKILLISHKILL Mmilitaryilitary Ssupplyupply Hubhub Ooff Thethe Aamericanmerican Rrevolutionevolution

Staples® Print Solutions HUNRES_1518351_BRO01 QA6 1234 CYANMAGENTAYELLOWBLACK 06/6/2016 This material is based upon work assisted by a grant from the Department of Interior, National Park Service. Any opinions, fi ndings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily refl ect the views of the Department of the Interior. FFISHKILLISHKILL MMilitaryilitary SSupplyupply HHubub ooff tthehe AAmericanmerican RRevolutionevolution 11776-1783776-1783 “...the principal depot of Washington’s army, where there are magazines, hospitals, workshops, etc., which form a town of themselves...” -Thomas Anburey 1778 Friends of the Fishkill Supply Depot A Historical Overview www.fi shkillsupplydepot.org Cover Image: Spencer Collection, New York Public Library. Designed and Written by Hunter Research, Inc., 2016 “View from Fishkill looking to West Point.” Funded by the American Battlefi eld Protection Program Th e New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1820. Staples® Print Solutions HUNRES_1518351_BRO01 QA6 5678 CYANMAGENTAYELLOWBLACK 06/6/2016 Fishkill Military Supply Hub of the American Revolution In 1777, the British hatched a scheme to capture not only Fishkill but the vital Fishkill Hudson Valley, which, if successful, would sever New England from the Mid- Atlantic and paralyze the American cause. The main invasion force, under Gen- eral John Burgoyne, would push south down the Lake Champlain corridor from Distribution Hub on the Hudson Canada while General Howe’s troops in New York advanced up the Hudson. In a series of missteps, Burgoyne overestimated the progress his army could make On July 9, 1776, New York’s Provincial Congress met at White Plains creating through the forests of northern New York, and Howe deliberately embarked the State of New York and accepting the Declaration of Independence. -

Patrick Henry's Integrity Patrick Henry Was Born in Virginia in 1736 When Virginia Was Still a British Colony

Patrick Henry's Integrity Patrick Henry was born in Virginia in 1736 when Virginia was still a British colony. He became a lawyer when he was 24 years old and quickly became well known for his eloquent work in the legal case known as the Parsons' Cause. This case was significant because it argued whether the colonial government or the British crown should make financial decisions for the colonies. About five years before, the Two Penny Act restricted the pay of ministers of the Anglican church (parsons) during a drought year in which the price of tobacco jumped higher (high demand, low supply). Parsons were paid in those days with tobacco, which had a value of about 2 cents a pound. The Two Penny Act of Virginia, enacted by the colonial government [that is, Virginia's government, not England's], maintained that parsons continue to earn 2 cents despite the higher price of tobacco. The parsons protested this because they believed they should benefit from the increased value of tobacco. The parsons appealed to authorities in England, who overruled [set aside, didn't enforce] the Two Penny Act. This judgment by England angered colonialists who believed England had no right to interfere in the colony's financial decision making. Although the Two Penny Act lasted only a year, some parsons sued for back wages. Patrick Henry argued in the case against one parson for the state's right to make its own laws. Although the parson won the case, he was awarded only a penny in back pay. Henry’s success launched a new recognition of his skills. -

Some Perspectives on Its Purpose from Published Accounts Preston E

SOME PERSPECTIVES ON ITS PURPOSE FROM PUBLISHED ACCOUNTS PRESTON E. PIERCE ONTARIO COUNTY HISTORIAN DEPARTMENT OF RECORDS, ARCHIVES AND INFORMATION MANAGEMENT ERVICES CANANDAIGUA, NEW YORK 2019 (REPRINTED, UPDATED, AND REVISED 2005, 1985) 1 Front cover image: Sullivan monument erected at the entrance to City Pier on Lake Shore Drive, Canandaigua. Sullivan-Clinton Sesquicentennial Commission, 1929. Bronze tablet was a common feature of all monuments erected by the Commission. Image from original postcard negative, circa 1929, in possession of the author. Above: Sullivan-Clinton Sesquicentennial Commission tablet erected at Kashong (Yates County), Rt. 14, south of Geneva near the Ontario County boundary. 1929. Image by the author. 2004 2 Gen. John Sullivan. Image from Benson J. Lossing, Pictorial Field Book of the Revolution. v. I. 1860. p. 272. 3 Sullivan-Clinton Campaign monument (front and back) erected in 1929 in Honeoye. Moved several times, it commemorates the location of Ft. Cummings, a temporary base established by Sullivan as he began the final leg of his march to the Genesee River. Images by the author. Forward 4 1979 marked the 200th anniversary of the Sullivan-Clinton expedition against those Iroquois nations that allied themselves with Britain and the Loyalists during the American Revolution. It is a little-understood (more often misunderstood) military incursion with diplomatic, economic, and decided geo-political consequences. Unfortunately, most people, including most municipal historians, know little about the expedition beyond what is recorded on roadside markers. In 1929, during the sesquicentennial celebrations of the American Revolution, the states of New York and Pennsylvania established a special commission that produced a booklet, sponsored local pageants, and erected many commemorative tablets in both states. -

The Ambiguous Patriotism of Jack Tar in the American Revolution Paul A

Loyalty and Liberty: The Ambiguous Patriotism of Jack Tar in the American Revolution Paul A. Gilje University of Oklahoma What motivated JackTar in the American Revolution? An examination of American sailors both on ships and as prisoners of war demonstrates that the seamen who served aboard American vessels during the revolution fit neither a romanticized notion of class consciousness nor the ideal of a patriot minute man gone to sea to defend a new nation.' While a sailor could express ideas about liberty and nationalism that matched George Washington and Ben Franklin in zeal and commitment, a mixxture of concerns and loyalties often interceded. For many sailors the issue was seldom simply a question of loyalty and liberty. Some men shifted their position to suit the situation; others ex- pressed a variety of motives almost simultaneously. Sailors could have stronger attachments to shipmates or to a hometown, than to ideas or to a country. They might also have mercenary motives. Most just struggled to survive in a tumultuous age of revolution and change. Jack Tar, it turns out, had his own agenda, which might hold steadfast amid the most turbulent gale, or alter course following the slightest shift of a breeze.2 In tracing the sailor's path in these varying winds we will find that seamen do not quite fit the mold cast by Jesse Lemisch in his path breaking essays on the "inarticulate" Jack Tar in the American Revolution. Lemisch argued that the sailor had a concern for "liberty and right" that led to a "complex aware- ness that certain values larger than himself exist and that he is the victim not only of cruelty and hardship but also, in the light of those values, of injus- tice."3 Instead, we will discover that sailors had much in common with their land based brethren described by the new military historians. -

The Impact of Weather on Armies During the American War of Independence, 1775-1781 Jonathan T

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2011 The Force of Nature: The Impact of Weather on Armies during the American War of Independence, 1775-1781 Jonathan T. Engel Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES THE FORCE OF NATURE: THE IMPACT OF WEATHER ON ARMIES DURING THE AMERICAN WAR OF INDEPENDENCE, 1775-1781 By JONATHAN T. ENGEL A Thesis submitted to the Department of History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2011 The members of the committee approve the thesis of Jonathan T. Engel defended on March 18, 2011. __________________________________ Sally Hadden Professor Directing Thesis __________________________________ Kristine Harper Committee Member __________________________________ James Jones Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members. ii This thesis is dedicated to the glory of God, who made the world and all things in it, and whose word calms storms. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Colonies may fight for political independence, but no human being can be truly independent, and I have benefitted tremendously from the support and aid of many people. My advisor, Professor Sally Hadden, has helped me understand the mysteries of graduate school, guided me through the process of earning an M.A., and offered valuable feedback as I worked on this project. I likewise thank Professors Kristine Harper and James Jones for serving on my committee and sharing their comments and insights. -

Environment and Culture in the Northeastern Americas During the American Revolution Daniel S

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine Electronic Theses and Dissertations Fogler Library Spring 5-11-2019 Navigating Wilderness and Borderland: Environment and Culture in the Northeastern Americas during the American Revolution Daniel S. Soucier University of Maine, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/etd Part of the Canadian History Commons, Environmental Studies Commons, Military History Commons, Nature and Society Relations Commons, Other History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Soucier, Daniel S., "Navigating Wilderness and Borderland: Environment and Culture in the Northeastern Americas during the American Revolution" (2019). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 2992. https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/etd/2992 This Open-Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NAVIGATING WILDERNESS AND BORDERLAND: ENVIRONMENT AND CULTURE IN THE NORTHEASTERN AMERICAS DURING THE AMERICAN REVOLUTION By Daniel S. Soucier B.A. University of Maine, 2011 M.A. University of Maine, 2013 C.A.S. University of Maine, 2016 A THESIS Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (in History) The Graduate School University of Maine May, 2019 Advisory Committee: Richard Judd, Professor Emeritus of History, Co-Adviser Liam Riordan, Professor of History, Co-Adviser Stephen Miller, Professor of History Jacques Ferland, Associate Professor of History Stephen Hornsby, Professor of Anthropology and Canadian Studies DISSERTATION ACCEPTANCE STATEMENT On behalf of the Graduate Committee for Daniel S. -

Battles of Saratoga Date: ______

IS 228 Name: ________________________ Class: ____ .. American Revolution: The Battles of Saratoga Date: ___________________________________ During the summer of 1776, a powerful army under British General Sir William control of the entire river. Control of the Hudson could sever New England-the hot Howe invaded the New York City area. His professional troops defeated and bed of the rebellion-from the rest of the colonies. outmaneuvered General George Washington’s less trained forces. An ill advised The architect of the plan, General John Burgoyne, commanded the main thrust American invasion of Canada had come to an appalling end, its once confident through the Lake Champlain valley. Although the invasion had some initial success regiments reduced to a barely disciplined mob beset by smallpox and pursuing with the capture of Fort Ticonderoga, the realities of untamed terrain soon slowed British troops through the Lake the British triumphant advance into an Champlain Valley. agonizing crawl. Worse for the British, a major As 1776 ended, the cause for column en route to seek supplies in Vermont American Independence seemed all but was overrun, costing Burgoyne almost lost. It was true that Washington’s irreplaceable 1000 men. Hard on the heels of successful gamble at the battles of this disaster, Burgoyne’s contingent of Native Trenton and Princeton kept hopes alive, Americans decided to leave, word came from but the British were still holding the the west that the second British column was initiative. Royal Garrisons held New stalled by the American controlled Fort Stanwix York and its immediate environs, and that the main British army would not be Newport, Rhode Island and Canada. -

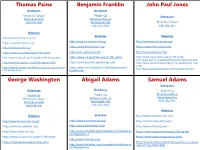

Benjamin Franklin John Paul Jones Databases Databases

Thomas Paine Benjamin Franklin John Paul Jones Databases Databases Britannica School Pebble-Go Databases Word Book Kids Britannica School Kids Info. Bits Word Book Kids Britannica School Kids Info. Bits Kids Info. Bits Websites Websites Websites http://www.mountvernon.org/ http://www.mountvernon.org/ http://www.mountvernon.org/ https://www.historyisfun.org/ http://www.ushistory.org/ https://www.historyisfun.org/ https://www.historyisfun.org/ https://www.cia.gov/kids-page/k-5th-grade http://www.ushistory.org/ http://www.ushistory.org/ http://www.let.rug.nl/usa/biographies/thomas-paine/ https://www.cia.gov/kids-page/k-5th-grade https://www.cia.gov/kids-page/k-5th-grade http://www.navy.mil/navydata/traditions/html/jpjones.html http://www.historyguide.org/intellect/paine.html https://www.bostonteapartyship.com/ https://www.nps.gov/revwar/about_the_revolution/jp_jone s.html http://www.ducksters.com/history/american_revolution/t https://www.fi.edu/benjamin-franklin/benjamin- http://www.eyewitnesstohistory.com/johnpauljones.htm homas_paine.php franklin-faq George Washington Abigail Adams Samuel Adams Databases Databases Databases Pebble-Go Pebble-Go Pebble-Go Britannica School Britannica School Britannica School Word Book Kids Word Book Kids Word Book Kids Kids Info. Bits Kids Info. Bits Kids Info. Bits Websites Websites Websites http://www.mountvernon.org/ http://www.mountvernon.org/ http://www.mountvernon.org/ https://www.historyisfun.org/ https://www.historyisfun.org/ https://www.historyisfun.org/ http://www.ushistory.org/ http://www.ushistory.org/