Catawba Population Dynamics During the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The People of the Falling Star

Patricia Lerch. Waccamaw Legacy: Contemporary Indians Fight for Survival. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2004. xvi + 168 pp. $57.50, cloth, ISBN 978-0-8173-1417-0. Reviewed by Thomas E. Ross Published on H-AmIndian (March, 2007) Patricia Lerch has devoted more than two presents rational assumptions about the Wacca‐ decades to the study of the Waccamaw Siouan, a maw tribe's links to colonial Indians of southeast‐ non-federally recognized Indian tribe (the tribe is ern North Carolina and the Cape Fear River recognized by the State of North Carolina) living drainage basin. in southeastern North Carolina. Her book is the She has no reservations about accepting the first volume devoted to the Waccamaw. It con‐ notion that Indians living in the region were re‐ tains nine chapters and includes sixteen photo‐ ferred to as Waccamaw, Cape Fear Indians, and graphs, fourteen of which portray the Waccamaw Woccon. Whatever the name of Indians living in during the period from 1949 to the present. The the Cape Fear region during the colonial period, first four chapters provide background material they had to react to the European advance. In on several different Indian groups in southeast‐ some instances, the Indians responded to violence ern North Carolina and northeastern South Car‐ with violence, and to diplomacy and trade with olina, and are not specific to the Waccamaw Indi‐ peace treaties; they even took an active role in the ans. Nevertheless, they are important in setting Indian Wars and the enslavement of Africans. The the stage for the chapters that follow and for pro‐ records, however, do no detail what eventually viding a broad, historical overview of the Wacca‐ happened to the Indians of the Cape Fear. -

Tuscarora Trails: Indian Migrations, War, and Constructions of Colonial Frontiers

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 2007 Tuscarora trails: Indian migrations, war, and constructions of colonial frontiers Stephen D. Feeley College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the Indigenous Studies Commons, Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Feeley, Stephen D., "Tuscarora trails: Indian migrations, war, and constructions of colonial frontiers" (2007). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539623324. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-4nn0-c987 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Tuscarora Trails: Indian Migrations, War, and Constructions of Colonial Frontiers Volume I Stephen Delbert Feeley Norcross, Georgia B.A., Davidson College, 1996 M.A., The College of William and Mary, 2000 A Dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty of the College of William and Mary in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Lyon Gardiner Tyler Department of History The College of William and Mary May, 2007 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. APPROVAL SHEET This dissertation is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Stephen Delbert F eele^ -^ Approved by the Committee, January 2007 MIL James Axtell, Chair Daniel K. Richter McNeil Center for Early American Studies 11 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. -

Louise Pettus Papers - Accession 1237

Winthrop University Digital Commons @ Winthrop University Manuscript Collection Louise Pettus Archives and Special Collections 2019 Louise Pettus Papers - Accession 1237 Mildred Louise Pettus South Carolina History Winthrop University History Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.winthrop.edu/ manuscriptcollection_findingaids Finding Aid Citation Louise Pettus Archives and Special Collections, Winthrop University, "Louise Pettus Papers - Accession 1237". Finding Aid 1135. https://digitalcommons.winthrop.edu/manuscriptcollection_findingaids/1135 This Finding Aid is brought to you for free and open access by the Louise Pettus Archives and Special Collections at Digital Commons @ Winthrop University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Manuscript Collection by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Winthrop University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WINTHROP UNIVERSITY LOUISE PETTUS ARCHIVES & SPECIAL COLLECTIONS MANUSCRIPT COLLECTION ACCESSION 1237 LOUISE PETTUS PAPERS 1300s-2000s 127 Boxes, 459 Folders, & 124 Bound Volumes Louise Pettus Papers, Acc. 1237 Manuscript Collection, Winthrop University Archives WINTHROP UNIVERSITY LOUISE PETTUS ARCHIVES & SPECIAL COLLECTIONS MANUSCRIPT COLLECTION ACC. NO.: 1237 PROCESSED BY: Carson Cope ADDITIONS: ___, ___, ___ DATE: _August 9, 2019_ NO. OF SECTIONS: 10 LOUISE PETTUS PAPERS I The papers of Louise Pettus, educator, historian, and author, were received as a gift to the Louise Pettus Archives over a period of several years from 2013 to 2018. Linear feet of shelf space occupied: 32.5 Approximate number of pieces: 60,000 pieces & 83 bound volumes Restrictions: Open to researchers under the rules and regulations of the Louise Pettus Archives & Special Collections at Winthrop University. Literary Rights: For information concerning literary rights please contact the Louise Pettus Archives & Special Collections at Winthrop University. -

Site 3 40 Acre Rock

SECTION 3 PIEDMONT REGION Index Map to Study Sites 2A Table Rock (Mountains) 5B Santee Cooper Project (Engineering & l) 2B Lake Jocassee Region (Energy 6A Congaree Swamp (Pristine Forest) Produ tion) 3A Forty Acre Rock (Granite 7A Lake Marion (Limestone Outcropping) Ot i ) 3B Silverstreet (Agriculture) 8A Woods Bay (Preserved Carolina Bay) 3C Kings Mountain (Historical 9A Charleston (Historic Port) Battleground) 4A Columbia (Metropolitan Area) 9B Myrtle Beach (Tourist Area) 4B Graniteville (Mining Area) 9C The ACE Basin (Wildlife & Sea Island ulture) 4C Sugarloaf Mountain (Wildlife Refuge) 10A Winyah Bay (Rice Culture) 5A Savannah River Site (Habitat 10B North Inlet (Hurricanes) Restoration) TABLE OF CONTENTS FOR SECTION 3 PIEDMONT REGION - Index Map to Piedmont Study Sites - Table of Contents for Section 3 - Power Thinking Activity - "The Dilemma of the Desperate Deer" - Performance Objectives - Background Information - Description of Landforms, Drainage Patterns, and Geologic Processes p. 3-2 . - Characteristic Landforms of the Piedmont p. 3-2 . - Geographic Features of Special Interest p. 3-3 . - Piedmont Rock Types p. 3-4 . - Geologic Belts of the Piedmont - Influence of Topography on Historical Events and Cultural Trends p. 3-5 . - The Catawba Nation p. 3-6 . - figure 3-1 - "Great Seal and Map of Catawba Nation" p. 3-6 . - Catawba Tales p. 3-6 . - story - "Ye Iswa (People of the River)" p. 3-7 . - story - "The Story of the First Woman" p. 3-8 . - story - "The Woman Who Became an Owl" p. 3-8 . - story - "The Legend of the Comet" p. 3-8 . - story - "The Legend of the Brownies" p. 3-8 . - story - "The Rooster and the Fox" p. -

Native Americans in the Cape Fear, by Dr. Jan Davidson

Native Americans in the Cape Fear, By Dr. Jan Davidson Archaeologists believe that Native Americans have lived in what is now the state of North Carolina for more than 13,000 years. These first inhabitants, now called Paleo-Indians by experts, were likely descended from people who came over a then-existing land bridge from Asia.1 Evidence had been found at Town Creek Mound that suggests Indians lived there as early as 11000 B.C.E. Work at another major North Carolinian Paleo-Indian where Indian artifacts have been found in layers of the soil, puts Native Americans on that land before 8000 B.C.E. That site, in North Carolina’s Uwharrie Mountains, near Badin, became an important source of stone that Paleo and Archaic period Indians made into tools such as spears.2 It is harder to know when the first people arrived in the lower Cape Fear. The coastal archaeological record is not as rich as it is in some other regions. In the Paleo-Indian period around 12000 B.C.E., the coast was about 60 miles further out to sea than it is today. So land where Indians might have lived is buried under water. Furthermore, the coastal Cape Fear region’s sandy soils don’t provide a lot of stone for making tools, and stone implements are one of the major ways that archeologists have to trace and track where and when Indians lived before 2000 B.C.E.3 These challenges may help explain why no one has yet found any definitive evidence that Indians were in New Hanover County before 8000 B.C.E.4 We may never know if there were indigenous people here before the Archaic period began in approximately 8000 B.C.E. -

Catawba Militarism: Ethnohistorical and Archaeological Overviews

CATAWBA MILITARISM: ETHNOHISTORICAL AND ARCHAEOLOGICAL OVERVIEWS by Charles L. Heath Abstract While many Indian societies in the Carolinas disappeared into the multi-colored fabric of Southern history before the mid-1700s, the Catawba Nation emerged battered, but ethnically viable, from the chaos of their colonial experience. Later, the Nation’s people managed to circumvent Removal in the 1830s and many of their descendants live in the traditional Catawba homeland today. To achieve this distinction, colonial and antebellum period Catawba leaders actively affected the cultural survival of their people by projecting a bellicose attitude and strategically promoting Catawba warriors as highly desired military auxiliaries, or “ethnic soldiers,” of South Carolina’s imperial and state militias after 1670. This paper focuses on Catawba militarism as an adaptive strategy and further elaborates on the effects of this adaptation on Catawba society, particularly in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. While largely ethnohistorical in content, potential archaeological aspects of Catawba militarism are explored to suggest avenues for future research. American Indian societies in eastern North America responded to European imperialism in countless ways. Although some societies, such as the Powhatans and the Yamassees (Gleach 1997; Lee 1963), attempted to aggressively resist European hegemony by attacking their oppressors, resistance and adaptation took radically different forms in a colonial world oft referred to as a “tribal zone,” a “shatter zone,” or the “violent edge of empire” (Ethridge 2003; Ferguson and Whitehead 1999a, 1999b). Perhaps unique among their indigenous contemporaries in the Carolinas, the ethnically diverse peoples who came to form the “Catawba Nation” (see Davis and Riggs this volume) proactively sought to ensure their socio- political and cultural survival by strategically positioning themselves on the southern Anglo-American frontier as a militaristic society of “ethnic soldiers” (see Ferguson and Whitehead 1999a, 1999b). -

Conservation Chat History of Catawba River Presentation

SAVE LAND IN Perpetuity 17,000+ acres conserved across 7 counties 4 Focus Areas: • Clean Water • Wildlife Habitat • Local Farms • Connections to Nature Urbanization: Our disappearing green space 89,600 acres 985,600 acres 1,702,400 acres Example - Riverbend Protect from development on Johnson Creek Threat to Mountain Island Lake Critical drinking water supply Mecklenburg and Gaston Counties Working with developer and: City of Charlotte Charlotte Water Char-Meck Storm Water Gaston County Mt Holly Clean water Saving land protects water quality, quantity Silt, particulates, contamination Spills and fish kills Rusty Rozzelle Water Quality Program Manager, Mecklenburg County Member of the Catawba- Wateree Water Management Group Catawba - Wateree System 1200 feet above mean sea level Lake Rhodhiss Statesville Lake Hickory Lookout Shoals Lake James Hickory Morganton Marion Lake Norman Catawba Falls 2,350 feet above mean sea N Lincoln County level Mountain Island Lake • River Channel = 225 miles Gaston County Mecklenburg • Streams and Rivers = 3,285 miles County • Surface Area of Lakes = 79,895 acres (at full pond) N.C. • Basin Area = 4,750 square miles Lake Wylie • Population = + 2,000,000 S.C. Fishing Creek Reservoir Great Falls Reservoir Rocky Creek Lake Lake Wateree 147.5 feet above mean sea level History of the Catawba River The Catawba River was formed in the same time frame as the Appalachian Mountains about 220 millions years ago during the early Mesozoic – Late Triassic period Historical Inhabitants of the Catawba • 12,000 years ago – Paleo Indians inhabited the Americas migrating from northern Asia. • 6,000 years ago – Paleo Indians migrated south settling along the banks of the Catawba River obtaining much of their sustenance from the river. -

Waccamaw River Blue Trail

ABOUT THE WACCAMAW RIVER BLUE TRAIL The Waccamaw River Blue Trail extends the entire length of the river in North and South Carolina. Beginning near Lake Waccamaw, a permanently inundated Carolina Bay, the river meanders through the Waccamaw River Heritage Preserve, City of Conway, and Waccamaw National Wildlife Refuge before merging with the Intracoastal Waterway where it passes historic rice fields, Brookgreen Gardens, Sandy Island, and ends at Winyah Bay near Georgetown. Over 140 miles of river invite the paddler to explore its unique natural, historical and cultural features. Its black waters, cypress swamps and tidal marshes are home to many rare species of plants and animals. The river is also steeped in history with Native American settlements, Civil War sites, rice and indigo plantations, which highlight the Gullah-Geechee culture, as well as many historic homes, churches, shops, and remnants of industries that were once served by steamships. To protect this important natural resource, American Rivers, Waccamaw RIVERKEEPER®, and many local partners worked together to establish the Waccamaw River Blue Trail, providing greater access to the river and its recreation opportunities. A Blue Trail is a river adopted by a local community that is dedicated to improving family-friendly recreation such as fishing, boating, and wildlife watching and to conserving riverside land and water resources. Just as hiking trails are designed to help people explore the land, Blue Trails help people discover their rivers. They help communities improve recreation and tourism, benefit local businesses and the economy, and protect river health for the benefit of people, wildlife, and future generations. -

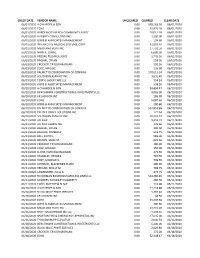

Check Date Vendor Name Uncleared Cleared Clear

CHECK DATE VENDOR NAME UNCLEARED CLEARED CLEAR DATE 06/01/2020 A O HARDEE & SON 0.00 939,163.50 06/01/2020 06/01/2020 ECHO 0.00 33,425.26 06/01/2020 06/01/2020 GARDEN CITY BEACH COMMUNITY ASSOC 0.00 10,012.74 06/01/2020 06/01/2020 HAGERTY CONSULTING INC 0.00 3,200.00 06/01/2020 06/01/2020 GORE & ASSOCIATES MANAGEMENT 0.00 124.80 06/01/2020 06/01/2020 INTERACTIVE MEDICAL SYSTEMS, CORP 0.00 32,803.67 06/01/2020 06/01/2020 MEAD AND HUNT INC 0.00 17,731.58 06/01/2020 06/01/2020 NAPIER, JOHN L 0.00 6,600.00 06/01/2020 06/01/2020 REDSAIL TECHNOLOGIES 0.00 2,745.50 06/01/2020 06/03/2020 BAGNAL, DYLAN 0.00 258.50 06/03/2020 06/03/2020 CROCKER, TAYLOR MORGAN 0.00 292.50 06/03/2020 06/03/2020 EDGE, MAGGIE 0.00 235.00 06/03/2020 06/03/2020 PALMETTO CORPORATION OF CONWAY 0.00 170,612.34 06/03/2020 06/03/2020 SOUTHERN ASPHALT INC 0.00 3,631.40 06/03/2020 06/03/2020 TERRYS LASER CARE LLC 0.00 354.24 06/03/2020 06/04/2020 GORE & ASSOCIATES MANAGEMENT 0.00 538.56 06/04/2020 06/10/2020 A O HARDEE & SON 0.00 94,894.47 06/10/2020 06/10/2020 BENCHMARK CONSTRUCTION & INVESTMENTS LLC 0.00 4,965.00 06/10/2020 06/10/2020 CR JACKSON INC 0.00 185.09 06/10/2020 06/10/2020 ECHO 0.00 5,087.66 06/10/2020 06/10/2020 GORE & ASSOCIATES MANAGEMENT 0.00 280.80 06/10/2020 06/10/2020 PALMETTO CORPORATION OF CONWAY 0.00 593,853.86 06/10/2020 06/10/2020 PEE DEE OFFICE SOLUTIONS INC 0.00 171.54 06/10/2020 06/10/2020 SOUTHERN ASPHALT INC 0.00 20,351.57 06/10/2020 06/11/2020 ASI FLEX 0.00 9,252.72 06/11/2020 06/11/2020 ASI FLEX ADMIN FEE 0.00 176.66 06/11/2020 06/11/2020 BAGNAL, DYLAN 0.00 280.50 06/11/2020 06/11/2020 BASHOR, KIMBERLY 0.00 618.75 06/11/2020 06/11/2020 BELL, JOYCE L 0.00 583.00 06/11/2020 06/11/2020 BROWN, SADIE M. -

History of Mecklenburg County and the City Of

2 THE LIBRARY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF NORTH CAROLINA AT CHAPEL HILL THE COLLECTION OF NORTH CAROLINIANA C971.60 T66m v. c.2 UNIVERSITY OF N.C. AT CHAPEL HILL 00015565808 This book is due on the last date stamped below unless recalled sooner. It may be renewed only once and must be brought to the North Carolina Collection for renewal. —H 1979 <M*f a 2288 *» 1-> .._ ' < JoJ Form No. A- 369 BRITISH MAP OF MECKLENBURG IN 1780. History of Mecklenburg County AND The City of Charlotte From 1740 to 1903. BY D. A. TOMPKINS, Author of Cotton and Cotton Oil; Cotton Mill, Commercial Features ; Cotton Values in Tex- Fabrics Cotton Mill, tile ; Processes and Calculations ; and American Commerce, Its Expansion. Charlotte, N. C, 1903. VOLUME TWO—APPENDIX. CHARLOTTE, N. C: Observer Printing House. 1903. COPYRIGHT, 1904. BY I). \. TOMPKINS. EXPLANATION. This history is published in two volumes. The first volume contains the simple narrative, and the second is in the nature of an appendix, containing- ample discussions of important events, a collection of biographies and many official docu- ments justifying and verifying- the statements in this volume. At the end of each chapter is given the sources of the in- formation therein contained, and at the end of each volume is an index. PREFACE. One of the rarest exceptions in literature is a production devoid of personal feeling. Few indeed are the men, who, realizing that the responsibility for their writings will be for them alone to bear, will not utilize the advantage for the promulgation of things as they would like them to be. -

8 Tribes, 1 State: Native Americans in North Carolina

8 Tribes, 1 State: North Carolina’s Native Peoples As of 2014, North Carolina has 8 state and federally recognized Native American tribes. In this lesson, students will study various Native American tribes through a variety of activities, from a PowerPoint led discussion, to a study of Native American art. The lesson culminates with students putting on a Native American Art Show about the 8 recognized tribes. Grade 8 Materials “8 Tribes, 1 State: Native Americans in North Carolina” PowerPoint, available here: o http://civics.sites.unc.edu/files/2014/06/NCNativeAmericans1.pdf o To view this PDF as a projectable presentation, save the file, click “View” in the top menu bar of the file, and select “Full Screen Mode”; upon completion of presentation, hit ESC on your keyboard to exit the file o To request an editable PPT version of this presentation, send a request to [email protected] “Native American Art Handouts #1 – 7”, attached North Carolina Native American Tribe handouts, attached o Lumbee o Eastern Band of Cherokee o Coharie o Haliwa-‑ Saponi o Meherrin o Occaneechi Band of the Saponi Nation o Sappony o Waccamaw Siouan “Create a Native American Art Exhibition” handout, attached “Native Americans in North Carolina Fact Sheet”, attached Brown paper or brown shopping bags (for the culminating project) Graph paper (for the culminating project) Art supplies (markers, colored pencils, crayons, etc. Essential Questions: What was life like for Native Americans before the arrival of Europeans? What happened to most Native American tribes after European arrival? What hardships have Native Americans faced throughout their history? How many state and federally recognized tribes are in North Carolina today? Duration 90 – 120 minutes Teacher Preparation A note about terminology: For this lesson, the descriptions Native American and American Indian are 1 used interchangeably when referring to more than one specific tribe. -

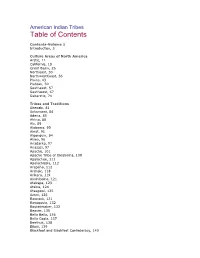

Table of Contents

American Indian Tribes Table of Contents Contents-Volume 1 Introduction, 3 Culture Areas of North America Arctic, 11 California, 19 Great Basin, 26 Northeast, 30 NorthwestCoast, 36 Plains, 43 Plateau, 50 Southeast, 57 Southwest, 67 Subarctic, 74 Tribes and Traditions Abenaki, 81 Achumawi, 84 Adena, 85 Ahtna, 88 Ais, 89 Alabama, 90 Aleut, 91 Algonquin, 94 Alsea, 96 Anadarko, 97 Anasazi, 97 Apache, 101 Apache Tribe of Oklahoma, 108 Apalachee, 111 Apalachicola, 112 Arapaho, 112 Archaic, 118 Arikara, 119 Assiniboine, 121 Atakapa, 123 Atsina, 124 Atsugewi, 125 Aztec, 126 Bannock, 131 Bayogoula, 132 Basketmaker, 132 Beaver, 135 Bella Bella, 136 Bella Coola, 137 Beothuk, 138 Biloxi, 139 Blackfoot and Blackfeet Confederacy, 140 Caddo tribal group, 146 Cahuilla, 153 Calusa, 155 CapeFear, 156 Carib, 156 Carrier, 158 Catawba, 159 Cayuga, 160 Cayuse, 161 Chasta Costa, 163 Chehalis, 164 Chemakum, 165 Cheraw, 165 Cherokee, 166 Cheyenne, 175 Chiaha, 180 Chichimec, 181 Chickasaw, 182 Chilcotin, 185 Chinook, 186 Chipewyan, 187 Chitimacha, 188 Choctaw, 190 Chumash, 193 Clallam, 194 Clatskanie, 195 Clovis, 195 CoastYuki, 196 Cocopa, 197 Coeurd'Alene, 198 Columbia, 200 Colville, 201 Comanche, 201 Comox, 206 Coos, 206 Copalis, 208 Costanoan, 208 Coushatta, 209 Cowichan, 210 Cowlitz, 211 Cree, 212 Creek, 216 Crow, 222 Cupeño, 230 Desert culture, 230 Diegueño, 231 Dogrib, 233 Dorset, 234 Duwamish, 235 Erie, 236 Esselen, 236 Fernandeño, 238 Flathead, 239 Folsom, 242 Fox, 243 Fremont, 251 Gabrielino, 252 Gitksan, 253 Gosiute, 254 Guale, 255 Haisla, 256 Han, 256