Ibla Foundation Home Page 3/8/10 10:09 PM

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

El Amor Brujo

Luis Fernando Pérez piano Basque National Orchestra Carlo Rizzi direction MANUEL DE FALLA (1876-1946) Noches en los jardines de España - Nuits dans les jardins d’Espagne 1 - En el Generalife (Au Generalife) 2 - Danza lejana (Danse lointaine) 3 - En los jardines de la Sierra de Córdoba (Dans les jardins de la Sierra de Cordoue) El sombrero de tres picos - Trois danses du Tricorne 4 - Danza de los vecinos (Danse des voisins) 5 - Danza de la molinera (Danse de la meunière) 6 - Danza del molinero (Danse du meunier) 7 - Fantasía Bética - Fantaisie bétique El amor brujo (piano suite) - L´Amour sorcier (piano suite) 8 - Pantomima (Pantomine) 9 - Danza del fuego fatuo (Chanson du feu follet) 10 - Danza del terror (Danse de la terreur) 11 - El Círculo magico (Le cercle magique) 12 - Danza ritual del fuego (Danse du feu) Enregistrement réalisé les 11 et 12 avril 2013 à l’Auditorium de Bordeaux (plages 1 à 3) et du 15 au 17 juin 2013 à la Aula de Música de Alcalá de Henares (plages 4 à 12) / Direction artistique, prise de son et montage : Jiri Heger (plages 1 à 3) et José Miguel Martínez (plages 4 à 12) / Piano : Steinway D (plages 1 à 3) et Yamaha (plages 4 à 12) Accordeur : Gérard Fauvin (plages 1 à 3) et Leonardo Pizzollante (plages 4 à 12) / Conception et suivi artistique : René Martin, François-René Martin et Christian Meyrignac / Photos : Marine de Lafregeyre / Design : Jean-Michel Bouchet - LM Portfolio / Réalisation digipack : saga.illico / Fabriqué par Sony DADC Austria. / & © 2014 MIRARE, MIR 219 www.mirare.fr TRACKS 2 PLAGES CD MANUEL DE FALLA Nuits dans les jardins d’Espagne manière traditionnelle du concerto classico-romantique pour piano et orchestre. -

Leopold Stokowski, "Latin" Music, and Pan Americanism

Leopold Stokowski, "Latin" Music, and Pan Americanism Carol A. Hess C oNDUCTOR LEOPOLD Stokowski ( 1882-1977), "the rum and coca-cola school of Latin American whose career bridged the circumspect world of clas composers," neatly conflating the 1944 Andrews Sis sical music with HolJywood glitz. encounterecl in ters song with "serious" Latin American composition. 2 varying clegrecs both of these realms in an often Such elasticity fit Stokowski to a tcc. On thc one overlooked aspcct of his career: promoting the music hand, with his genius for bringing the classics to of Latín American and Spanish composers, primaril y the mass public, Stokowski was used to serving up those of the twentieth century. In the U.S .. Stokow ''light classics," as can be scen in hi s movies, which ski's adopted country. this repertory was often con include Wah Disney's Famasia of 1940 and One veniently labeled '·Latín." due as much to lack of Htmdred Men anda Girl of 1937. On the other hand. subtlety on thc part of marketcrs as thc less-than the superbly trained artist in Stokowski was both an nuanccd perspective of the public. which has often experimentcr and a promoter of new music. A self resisted dífferentiatíng the Spanish-speaking coun described "egocentric"-he later declared. " I always tries.1 In acldition to concert repertory, "Latin'' music want to he first"-Stokowski was always on the might include Spanish-language popular songs, lookout for novelty.3 This might in volve transcribing English-language songs on Spanish or Latín Ameri Bach for an orchestra undreamt of in the eighteenth can topics, or practically any work that incorporated century or premiering works as varied as Pierrot claves, güiro, or Phrygian melodic turns. -

Montserrat Caballé En El Teatro De La Zarzuela

MONTSERRAT CABALLÉ EN EL Comedia musical en dos actos TEATRO DE LA ZARZUELA Victor Pagán Estrenada en el Teatro Bretón de los Herreros de Logroño, el 12 de junio de 1947, y en el Teatro Albéniz de Madrid, el 30 de septiembre de 1947 Teatro de la Zarzuela Con la colaboración de ontserrat Caballé M en el Teatro de la Zarzuela1 1964-1992 1964 1967 ANTOLOGÍA DE LA TONADILLA Y LA VIDA BREVE LA TRAVIATA primera temporada oficial de ballet y teatro lírico iv festival de la ópera de madrid 19, 20, 21, 22, 24 de noviembre de 1964 4 de mayo de 1967 Guión de Alfredo Mañas y versión musical de Cristóbal Halffter Música de Giuseppe Verdi Libreto de Francesco Maria Piave, basado en Alexandre Dumas, hijo compañía de género lírico Montserrat Caballé (Violetta Valery) La consulta y La maja limonera (selección) Aldo Bottion (Alfredo Germont), Manuel Ausensi (Giorgio Germont), Textos y música de Fernando Ferrandiere y Pedro Aranaz Ana María Eguizabal (Flora Bervoix), María Santi (Annina), Enrique Suárez (Gastone), Juan Rico (Douphol), Antonio Lagar (Marquese D’Obigny), Silvano Pagliuga (Dottore Grenvil) Mari Carmen Ramírez (soprano), María Trivó (soprano) Ballet de Aurora Pons Coro de la Radiotelevisión Española La vida breve Orquesta Sinfónica Municipal de Valencia Música de Manuel de Falla Dirección musical Carlo Felice Cillario, Alberto Leone Libreto de Carlos Fernández Shaw Dirección de escena José Osuna Alberto Lorca Escenografía Umberto Zimelli, Ercole Sormani Vestuario Cornejo Montserrat Caballé (Salud) Coreografía Aurora Pons Inés Rivadeneira (Abuela), -

Don Carlo Cambió Mi Vida” Por Ingrid Haas

www.proopera.org.mx • año XXV • número 2 • marzo – abril 2017 • sesenta pesos CONCIERTOS Elīna Garanča en México ENTREVISTAS Dhyana Arom Jorge Cózatl Ricardo López Constantine Orbelian Arturo Rodríguez Torres Carlos Serrano Diego Silva Ramón Vargas ENTREVISTAS EN LÍNEA Markus Hinterhäuser Grigory Soloviev FerruccioFerruccio FurlanettoFurlanetto “Don Carlo “Don Carlo cambiócambió mimi vida”vida”pro opera¾ EN BREVE por Charles H. Oppenheim La Orquesta Filarmónica del Desierto en Bellas Artes Por vez primera desde su formación en 2014, la Orquesta Filarmónica del Desierto, con sede en Saltillo, Coahuila, ofreció un concierto el pasado 28 de enero en la sala principal del Palacio de Bellas Artes, dirigida por su titular, el maestro Natanael Espinoza. La orquesta interpretó la obertura de la ópera Rienzi de Richard Wagner, Tangata de agosto de Máximo Diego Pujol y la Sinfonía número 5 en Mi menor, op. 64 de Piotr Ilich Chaikovski. La tercera generación del Estudio de Ópera de Bellas Artes Foto: Ana Lourdes Herrera Concierto del EOBA en memoria de Rafael Tovar y de Teresa El último recital de la tercera generación del Estudio de Ópera de Bellas Artes (EOBA) se dedicó a la memoria del recién fallecido titular de la Secretaría de Cultura, Rafael Tovar y de Teresa, quien le dio un fuerte impulso a la agrupación creada apenas en 2014. En el recital participaron las sopranos Rosario Aguilar, María Caballero y Lorena Flores, las mezzosopranos Vanessa Jara e Isabel Stüber, los tenores Enrique Guzmán y Ángel Macías, el barítono Carlos López, el bajo-barítono Rodrigo Urrutia y el bajo Carlos Santos, acompañados por los pianistas Edgar Ibarra y Alain del Real. -

Copy of White and Yellow Violin Music Invitation Poster

D E K A L B Y O U T H S Y M P H O N Y O R C H E S T R A COME HEAR THE FUTURE T U E S D A Y M A Y 2 5 , 2 0 2 1 7 P M 5 4 T H S E A S O N D E K A L B Y O U T H S Y M H O N Y . C O M 54th season DYSO 2020-2021 From the Artistic Director Dear DYSO patron, Normally, when we look back at the past, we try to romanticize it with stories of exciting adventures and larger-than-life characters. The further back you go into the past, the more colorful the stories become. Until eventually, we turn our past into legends. Unlike the myths and legends of old, our reality over the past year has been anything but a romanticized adventure. Nearly every aspect of our lives has been recast in new and challenging contexts, transforming everyday experiences and tasks from simple and ordinary to difficult and extraordinary. This year has shown us the importance of persevering during difficult times and making a positive impact where we can and when we can. The way I see it, becoming a legend is not only reserved for mythological characters or figures of folklore. I have watched in awe, as a group of young musicians have become modern day legends by making a positive impact moment by moment, note by note. All in one night! Thank you for being with us to help create this modern day legend! PhilipBarnard Philip Barnard, Artistic Director Dekalb Youth Symphony Orchestra P.S. -

Nyco Renaissance

NYCO RENAISSANCE JANUARY 10, 2014 Table of Contents: 1. Executive Summary ...................................................................................................................... 2 2. History .......................................................................................................................................... 4 3. Core Values .................................................................................................................................. 5 4. The Operatic Landscape (NY and National) .............................................................................. 8 5. Opportunities .............................................................................................................................. 11 6. Threats ......................................................................................................................................... 13 7. Action Plan – Year 0 (February to August 2014) ......................................................................... 14 8. Action Plan – Year 1 (September 2014 to August 2015) ............................................................... 15 9. Artistic Philosophy ...................................................................................................................... 18 10. Professional Staff, Partners, Facilities and Operations ............................................................. 20 11. Governance and Board of Directors ......................................................................................... -

Issues in the English Critical Reception of the Three-Cornered Hat *

Issues in the English Critical Reception of The Three-Cornered Hat * Michael Christojoridis Another great night at the Russian ballet! I have never seen the Alhambra [theatre] looking more brilliant, or filled with a more enthusiastic audience than at the premiere of The Three-Comered Hat' on Tuesday. The uniform scheme of Peace decorations .. enhanced the nobility of one of the finest auditoriumsin Europe. As for the enthusiasm- it defies description. It was tremendous. There is no other word? The overwhelming success of The Three-Cornered Hat at its premiere in London in 1919 came at the end of the Ballets Russes' euphoric first post-war season. The dire wartime economic situation of the company had led Serge Diaghilev to embrace a broader public than the previous aristocratic clientele, beginning the season at the elevated music hall surrounds of the Coliseum. It was this new class of balletomanes that embraced Diaghilev's productions and provided the audience for English ballet in the following decade. Through an examination of the contemporary press, this paper will explore some of the issues underlying the popular and critical success of the ballet in London, and especially of Manuel de Falla's score. Unlike most of the Ballets Russes productions, The Three-Cornered Hat had not been the brainchild of Diaghilev, but had evolved gradually from an earlier project that Falla had worked on. In 1916 Gregorio and Maria Martinez Sierra had staged a mimed adaptation of Pedro Antonio de Alarc6n1s social comedy, El sombrero de tres picos (The Three-Cornered Hat), to a score for chamber ensemble by Falla. -

|||GET||| La Vida Breve / a Brief Life 1St Edition

LA VIDA BREVE / A BRIEF LIFE 1ST EDITION DOWNLOAD FREE Juan Carlos Onetti | 9788466334327 | | | | | La Vida Breve/A Brief Life Concurso de Cante Jondo Impressionism in music Spanish opera. Download as PDF Printable version. Following the Spanish Civil Warand devastated by the tragic murder of his friend Lorca, Falla left Spain in for Argentina. Literary Fiction. Refresh and try again. Work we must! Divadni rated it did not like it Jun 22, Inhe and some of his colleagues were imprisoned by the military dictatorship. Out with the establishment! La vida breve Opera by Manuel de Falla The composer in Hendrik rated it did not like it May 15, Only an hour long, the complete opera is seldom performed today, but its orchestral sections are, especially the act 2 music published as Interlude and Dancewhich is popular at concerts of Spanish La Vida Breve / a Brief Life 1st edition. He is interred in the Cementerio de la Almudena in Madrid. List of compositions by Manuel de Falla. Open Preview See a Problem? Lillian Grenville. He had suffered from severe ill health for many years, and this certainly limited his output. This flamboyant musician plays the grand piano like a virtuoso, at moments like a possessed demon, releasing the rip-tide tempo changes and atonality that hardly seem possible from a single keyboard. Already, Paco, the deceiver, is committed to marry another woman in his own class. Manuel de Falla - Spanish. Wikimedia Commons. More filters. Personen und Handlung sind schwach. Goodreads helps you keep track of La Vida Breve / a Brief Life 1st edition you want to read. -

Texto Completo (Pdf)

Recibido: 30/07/2012 Aceptado: 10/09/2012 Agustín Martínez Fernández Consideraciones sobre cuatro obras cimeras del pianismo falliano RESUMEN: Falla es uno de los compositores españoles más importantes. Su estética nacionalista, con miras hacia la universalización de su lenguaje, influenció a muchos compositores posteriores. Dos de sus obras capitales originales y dos transcripciones para piano de sus ballets más importantes son comentados. Son: Cuatro piezas españolas, Fantasía Baetica, El Amor Brujo y El Sombrero de Tres Picos. Se ofrecen consideraciones sobre ritmo, forma, influencias modales... PALABRAS CLAVE: Manuel de Falla, obras, piano, ballets, forma, influencias modales, ritmo, El Amor Brujo, Fantasía Baetica, El Sombrero de Tres Picos, Cuatro Piezas Españolas ABSTRACT: Falla is one of most important spanish composers. His aesthetic, nationalistic towards universal influenced many later composers. Two of his original capital piano works and two piano transcriptions of his most important ballets are commented. They are: Four Spanish Pieces, Fantasía Baética, Love Sorcier and Three Cornered Hat. Here are commented concerning rhythm, form, modal influencies... KEYWORDS: Manuel de Falla, works, piano, ballets, form, ritmo, modal influences, El Amor Brujo, Love Sorcier, Fantasía Baética, El Sombrero de Tres Picos, Three Cornered Hat, Cuatro Piezas Españolas, Four Spanish Pieces ___ Para este artículo he seleccionado cuatro obras de Manuel de Falla (1876-1946) de estética nacionalista. Dos de ellas corresponden a transcripciones de sus ballets más conocidos. Las otras dos fueron pensadas desde el instrumento. No obstante, las transcripciones muestran una lograda escritura específico-idiomática. El cuaderno de las Cuatro Piezas Españolas constituye, junto con su Fantasía Baética, una de las obras cumbre del pianismo del compositor gaditano, compartiendo ese puesto en el cénit de las colecciones pianísticas trascendentes con la Iberia albeniciana o las Goyescas de Granados. -

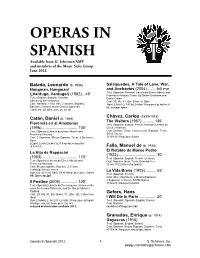

OPERAS in SPANISH Available from G

OPERAS IN SPANISH Available from G. Schirmer/AMP and members of the Music Sales Group June 2012 Balada, Leonardo (b. 1936) Salsipuedes, A Tale of Love, War, Hangman, Hangman! and Anchovies (2004)……. full eve Text: (Spanish, German) Libretto by Eliseo Alberto and (¡Verdugo, Verdugo!) (1982)…45' Francisco Hinojosa. Trans. By Shane Gasbarra and Text: (English, Spanish, Catalan) Daniel Catán Libretto by the composer Cast: 3S, Mz, 4T, Bar, B-bar, B, Spkr Cast: Narrator, Tenor, Alto, 2 Basses, Soprano, 3(pic).2.5(bcl).2/3.4Ctpt.2+btbn.1/timp.perc/pf.hp/4vc.4 Baritone, 2 actors; Mixed Chorus (optional) db; onstage 4perc cl(bcl), bn, tpt, btbn, perc, pf, vn, db Chávez, Carlos (1899-1978) Catán, Daniel (b. 1949) The Visitors (1957) .......... 135’ Florencia en al Amazonas Text: (Spanish, English, French, German) Libretto by (1996) ................................ 100’ Chester Kallman Text: (Spanish) Libretto by Eliseo Alberto and Cast: Baritone, Bass, Countertenor, Soprano, Tenor; Francisco Hinojosa SATB Chorus Cast: 2 Sopranos, Mezzo Soprano, Tenor, 2 Baritones, 3333/4331/timp.3perc/hp/str Bass 2(2pic).22+bcl.2(cbn)/3221.timp.4perc/hp.pf/str (4.4.4.4.3) Falla, Manuel de (b. 1938) El Retablo de Maese Pedro La Hija de Rappacini (1922) ................................... 30' (1983) ................................ 170’ Text: (Spanish, English, French, German) Text: (Spanish) Libretto by Eliseo Alberto and Cast: Soprano (boy), Tenor, Bass-baritone Francisco Hinojosa 12+ca.11/2100/perc/hp.hpd/str Cast: Mezzo-soprano, Soprano, 2 Tenors, 3 offstage female voices La Vida Breve (1905) .......... 65' 3(pic).2(rec).3(ca).3(bcl).3/4331/timp.3perc/pf.cel.hp/str Text: (Spanish, French) Alt: 2perc.hp.2pf Cast: Alto, 3 Baritones, 2 Mezzo Sopranos, 3 Sopranos, 2 Tenors; SATB Chorus Il Postino (2008) .............. -

Senior Recital: Lara Carr, Soprano

Upcoming Events at KSU in Music Friday, May 7 Georgia Young Singers 8:00 pm Stillwell Theater Kennesaw State University Saturday, May 8 Department of Music Junior Recital Musical Arts Series Danielle Hearn, flute presents 5:00 pm Music Building Recital Hall Senior Recital Shannon Hampton, clarinet 7:30 pm Music Building Recital Hall Lara Carr, soprano Friday, May 14 Senior Recital Huu Mai, piano Senior Recital 8:00 pm Stillwell Theater Sunday, May 23 Faculty Recital Christy Lambert, piano Oral Moses, bass-baritone 3:00 pm Music Building Recital Hall Thursday, May 6, 2004 8:00 p.m. Music Building Recital Hall 63rd concert of the 2003/2004 Musical Arts Series season This recital is presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Bachelor of Music in Performance. I. The pain of betrayal by a lover is expressed in the text, but the music sounds quite bright and cheerful for its spiteful words. This song, Les nuits d’été (Gautier) Hector Berlioz like the others, has a dance quality to it, which originates from its (1803-1869) folk form. Nana, a completely contrasting song and is calm, hushed, Villanelle and soothing. It is a lullaby sung by a mother to her baby, in which she beautifully expresses the intense and unique love a mother has How wonderful it will be when spring comes, my dear one, when nature will for her child. The rhythm of the piano is perfectly even, creating a hold new wonder and beauty for us to explore and enjoy together! lulling, rocking feeling. -

Christopher Parkening Guitarist

THE UNIVERSITY MUSICAL SOCIETY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN Christopher Parkening Guitarist FRIDAY EVENING, MARCH 18, 1988, AT 8:00 RACKHAM AUDITORIUM, ANN ARBOR, MICHIGAN PROGRAM Three Renaissance Lute Pieces ...................................... Anonymous Sonata in D major ........................................... MATEO ALBENIZ Danza .................................................. DIEGO DE TORRIJOS Suite espanola ................................................. CASPAR SANZ Espanoletas Folias Rujero y paradetas Pasacalle La minona de Cataluna Canaries Prelude from The Well-Tempered Clavier 1 Gavotte from Sixth Cello Suite 1 ........ JOHANN SEBASTIAN BACH Jesu, Joy of Man's Desiring from Cantata 147 J Villanesca (Spanish Dance No. 4) ......................... ENRIQUE GRANADOS Torre Bermeja ............................................... ISAAC ALBENIZ INTERMISSION Suite castillos de Espana .......................... FEDERICO MORENA TORROBA Rumor de Copla Montemayor (Contemplacion) Siguenza Turegano Manzanares del Real Two Preludes; Gavota-choro ............................ HEITOR VILLA-LOBOS Variations on a Theme of Handel, Op. 107 .................... MAURO GIULIANI Pause *Watkin's Ale ..................................................... Anonymous *Praise Ye the Lord from Vesperae solennes ......... WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART *De los alamos vengo, madre ............................... JOAQUI'N RODRIGO *Ciranda ...................................................... VILLA-LOBOS *Spanish Dance No. 1 from La vida breve ...................