Russian Olive (Elaeagnus Angustifolia L.) Plant Guide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

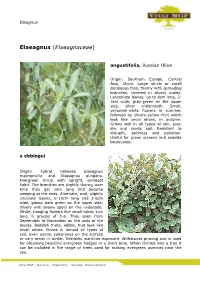

Elaeagnus (Elaeagnaceae)

Eleagnus Elaeagnus (Elaeagnaceae) angustifolia, Russian Olive Origin: Southern Europe, Central Asia, China. Large shrub or small deciduous tree, thorny with spreading branches, covered in silvery scales. Lanceolate leaves, up to 8cm long, 2- 3cm wide, grey-green on the upper side, silver underneath. Small, yellowish-white flowers in summer, followed by silvery-yellow fruit which look like small olives, in autumn. Grows well in all types of soil, even dry and sandy soil. Resistant to drought, saltiness and pollution. Useful for green screens and seaside boulevards. x ebbingei Origin: hybrid between Elaeagnus macrophylla and Elaeagnus pungens. Evergreen shrub with upright, compact habit. The branches are slightly thorny, over time they get very long and become weeping at the ends. Alternate, oval, slightly undulate leaves, 5-10cm long and 3-6cm wide, glossy dark green on the upper side, silvery with brown spots on the underside. White, hanging flowers like small tubes 1cm long in groups of 3-6. They open from September to November on the axils of the leaves. Reddish fruits, edible, that look like small olives. Grows in almost all types of soil, even sandy, calcareous on the surface or very moist in winter. Tolerates maritime exposure. Withstands pruning and is used for obtaining beautiful evergreen hedges in a short time. When formed into a tree it can be included in the range of trees used for making evergreen avenues near the sea. Vivai MGF – Nursery – Pépinières – Viveros - Baumschulen Eleagnus x ebbingei “Eleador”® Origin: France. Selection of Elaeagnus x ebbingei “Limelight”, from which it differs in the following ways: • in the first years it grows more in width and less in height; • the leaves are larger (7-12cm long, 4-6cm wide), and the central golden yellow mark is wider and reaches the margins; • it does not produce branches with all green leaves, but only an occasional branch which bears both variegated leaves and green leaves. -

Spiranthes Diluvialis Survey, 2004

Spiranthes diluvialis Survey, 2004 Final ROCKY REACH HYDROELECTRIC PROJECT FERC Project No. 2145 December 1, 2004 Prepared by: Beck Botanical Services Bellingham, WA Prepared for: Public Utility District No. 1 of Chelan County Wenatchee, Washington Rocky Reach Spiranthes diluvialis TABLE OF CONTENTS SECTION 1: INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................... 1 SECTION 2: METHODS......................................................................................................... 1 SECTION 3: RESULTS AND DISCUSSION.......................................................................... 2 3.1 Chelan Falls Population .................................................................................................................................3 3.2 Howard Flats Population................................................................................................................................4 3.3 Gallagher Flats Population .............................................................................................................................5 SECTION 4: CONCLUSIONS ................................................................................................ 5 SECTION 5: REFERENCES .................................................................................................. 6 Spiranthes diluvialis SurveyFinal Report Rocky Reach Project No. 2145 December 1, 2004 Page i SS/8504 Rocky Reach Spiranthes diluvialis LIST OF TABLES Table 1: General comparison of -

Phylogenetic Relationships in Korean Elaeagnus L. Based on Nrdna ITS Sequences

Korean J. Plant Res. 27(6):671-679(2014) Print ISSN 1226-3591 http://dx.doi.org/10.7732/kjpr.2014.27.6.671 Online ISSN 2287-8203 Original Research Article Phylogenetic Relationships in Korean Elaeagnus L. Based on nrDNA ITS Sequences OGyeong Son1, Chang Young Yoon2 and SeonJoo Park1* 1Department of Life Science, Yeungnam University, Gyeongsan 712-749, Korea 2Department of Biotechnology, Shingyeong University, Hwaseon 445-741, Korea Abstract - Molecular phylogenetic analyses of Korean Elaeagnus L. were conducted using seven species, one variety, one forma and four outgroups to evaluate their relationships and phylogeny. The sequences of internal transcribed spacer regions in nuclear ribosomal DNA were employed to construct phylogenetic relationships using maximum parsimony (MP) and Bayesian analysis. Molecular phylogenetic analysis revealed that Korean Elaeagnus was a polyphyly. E. umbellata var. coreana formed a subclade with E. umbellata. Additionally, the genetic difference between E. submacrophylla and E. macrophylla was very low. Moreover, E. submacrophylla formed a branch from E. macrophylla, indicating that E. submacrophylla can be regarded as a variety. However, several populations of this species were not clustered as a single clade; therefore, further study should be conducted using other molecular markers. Although E. glabra f. oxyphylla was distinct in morphological characters of leaf shape with E. glabra. But E. glabra f. oxyphylla was formed one clade by molecular phylogenetic with E. glabra. Additionally, this study clearly demonstrated that E. pungens occurs in Korea, although it was previously reported near South Korea in Japan and China. According to the results of ITS regions analyses, it showed a resolution and to verify the relationship between interspecies of Korean Elaeagnus. -

Plant Life of Western Australia

INTRODUCTION The characteristic features of the vegetation of Australia I. General Physiography At present the animals and plants of Australia are isolated from the rest of the world, except by way of the Torres Straits to New Guinea and southeast Asia. Even here adverse climatic conditions restrict or make it impossible for migration. Over a long period this isolation has meant that even what was common to the floras of the southern Asiatic Archipelago and Australia has become restricted to small areas. This resulted in an ever increasing divergence. As a consequence, Australia is a true island continent, with its own peculiar flora and fauna. As in southern Africa, Australia is largely an extensive plateau, although at a lower elevation. As in Africa too, the plateau increases gradually in height towards the east, culminating in a high ridge from which the land then drops steeply to a narrow coastal plain crossed by short rivers. On the west coast the plateau is only 00-00 m in height but there is usually an abrupt descent to the narrow coastal region. The plateau drops towards the center, and the major rivers flow into this depression. Fed from the high eastern margin of the plateau, these rivers run through low rainfall areas to the sea. While the tropical northern region is characterized by a wet summer and dry win- ter, the actual amount of rain is determined by additional factors. On the mountainous east coast the rainfall is high, while it diminishes with surprising rapidity towards the interior. Thus in New South Wales, the yearly rainfall at the edge of the plateau and the adjacent coast often reaches over 100 cm. -

Diseases of Trees in the Great Plains

United States Department of Agriculture Diseases of Trees in the Great Plains Forest Rocky Mountain General Technical Service Research Station Report RMRS-GTR-335 November 2016 Bergdahl, Aaron D.; Hill, Alison, tech. coords. 2016. Diseases of trees in the Great Plains. Gen. Tech. Rep. RMRS-GTR-335. Fort Collins, CO: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station. 229 p. Abstract Hosts, distribution, symptoms and signs, disease cycle, and management strategies are described for 84 hardwood and 32 conifer diseases in 56 chapters. Color illustrations are provided to aid in accurate diagnosis. A glossary of technical terms and indexes to hosts and pathogens also are included. Keywords: Tree diseases, forest pathology, Great Plains, forest and tree health, windbreaks. Cover photos by: James A. Walla (top left), Laurie J. Stepanek (top right), David Leatherman (middle left), Aaron D. Bergdahl (middle right), James T. Blodgett (bottom left) and Laurie J. Stepanek (bottom right). To learn more about RMRS publications or search our online titles: www.fs.fed.us/rm/publications www.treesearch.fs.fed.us/ Background This technical report provides a guide to assist arborists, landowners, woody plant pest management specialists, foresters, and plant pathologists in the diagnosis and control of tree diseases encountered in the Great Plains. It contains 56 chapters on tree diseases prepared by 27 authors, and emphasizes disease situations as observed in the 10 states of the Great Plains: Colorado, Kansas, Montana, Nebraska, New Mexico, North Dakota, Oklahoma, South Dakota, Texas, and Wyoming. The need for an updated tree disease guide for the Great Plains has been recog- nized for some time and an account of the history of this publication is provided here. -

Plantlists BMP Manual- April 30, 2008

Appendix B Charlotte-Mecklenburg Invasive and Exotic Plant List Infests Hydrologic Form Zone(s) 1 Scientific Name Common Name Family Wetland Indicator Status Invasive Exotic Tree 5, 6 Acer platanoides Maple, Norway Aceraceae NI 3, 4, 5, 6 Ailanthus altissima Tree of heaven Simaroubaceae NI 4, 5, 6 Albizia julibrissin Mimosa; Silk tree Fabaceae NI 3, 4, 5, 6 Broussonetia papyrifera Mulberry, Paper Moraceae NI 5, 6 Melia azedarach Chinaberry Meliaceae NI 4, 5, 6 Morus alba Mulberry, White or Common Moraceae FACU- 3, 4, 5, 6 Morus papyrifera (See Broussonetia papyrifera ) Moraceae NI 4, 5, 6 Paulownia tomentosa Empress or Princess tree Scrophulariaceae FACU 4, 5, 6 Populus balsamifera ssp. balsamifera Poplar, Balsam or Balm of Gilead Salicaceae FAC 5, 6 Quercus acutissima Oak, Sawtooth Fagaceae NI Invasive Exotic Shrub 4, 5, 6 Berberis thunbergii Barberry, Japanese Berberidaceae UPL Elaeagnus angustifolia Olive, Russian Oleaceae FAC Elaeagnus pungens Olive, Thorny Oleaceae NI Elaeagnus umbellata Olive, Autumn Oleaceae NI Eleutherococcus pentaphyllus Ginseng shrub; Fiveleaf Aralia Araliaceae NI Euonymus alata Spindletree, Winged or Burning Bush Celastraceae NI Euonymus fortunei Wintercreeper or Climbing Euonymus Celastraceae NI Ligustrum obtusifolium Privet, Border or Blunt-leaved Oleaceae NI Ligustrum sinense Privet, Chinese Oleaceae FAC Ligustrum villosum (See Ligustrum sinense ) Oleaceae NI Ligustrum vulgare Privet, European or Common Oleaceae NI Lonicera x bella Honeysuckle, Whitebell or Bell's Caprifoliaceae NI Lonicera fragrantissima -

Autumn Olive Elaeagnus Umbellata Thunberg and Russian Olive Elaeagnus Angustifolia L

Autumn olive Elaeagnus umbellata Thunberg and Russian olive Elaeagnus angustifolia L. Oleaster Family (Elaeagnaceae) DESCRIPTION Autumn olive and Russian olive are deciduous, somewhat thorny shrubs or small trees, with smooth gray bark. Their most distinctive characteristic is the silvery scales that cover the young stems, leaves, flowers, and fruit. The two species are very similar in appearance; both are invasive, however autumn olive is more common in Pennsylvania. Height - These plants are large, twiggy, multi-stemmed shrubs that may grow to a height of 20 feet. They occasionally occur in a single-stemmed, more tree-like form. Russian olive in flower Leaves - Leaves are alternate, oval to lanceolate, with a smooth margin; they are 2–4 inches long and ¾–1½ inches wide. The leaves of autumn olive are dull green above and covered with silvery-white scales beneath. Russian olive leaves are grayish-green above and silvery-scaly beneath. Like many other non-native, invasive plants, these shrubs leaf out very early in the spring, before most native species. Flowers - The small, fragrant, light-yellow flowers are borne along the twigs after the leaves have appeared in May. autumn olive in fruit Fruit - The juicy, round, edible fruits are about ⅓–½ inch in diameter; those of Autumn olive are deep red to pink. Russian olive fruits are yellow or orange. Both are dotted with silvery scales and produced in great quantity August–October. The fruits are a rich source of lycopene. Birds and other wildlife eat them and distribute the seeds widely. autumn olive and Russian olive - page 1 of 3 Roots - The roots of Russian olive and autumn olive contain nitrogen-fixing symbionts, which enhance their ability to colonize dry, infertile soils. -

Threats to Australia's Grazing Industries by Garden

final report Project Code: NBP.357 Prepared by: Jenny Barker, Rod Randall,Tony Grice Co-operative Research Centre for Australian Weed Management Date published: May 2006 ISBN: 1 74036 781 2 PUBLISHED BY Meat and Livestock Australia Limited Locked Bag 991 NORTH SYDNEY NSW 2059 Weeds of the future? Threats to Australia’s grazing industries by garden plants Meat & Livestock Australia acknowledges the matching funds provided by the Australian Government to support the research and development detailed in this publication. This publication is published by Meat & Livestock Australia Limited ABN 39 081 678 364 (MLA). Care is taken to ensure the accuracy of the information contained in this publication. However MLA cannot accept responsibility for the accuracy or completeness of the information or opinions contained in the publication. You should make your own enquiries before making decisions concerning your interests. Reproduction in whole or in part of this publication is prohibited without prior written consent of MLA. Weeds of the future? Threats to Australia’s grazing industries by garden plants Abstract This report identifies 281 introduced garden plants and 800 lower priority species that present a significant risk to Australia’s grazing industries should they naturalise. Of the 281 species: • Nearly all have been recorded overseas as agricultural or environmental weeds (or both); • More than one tenth (11%) have been recorded as noxious weeds overseas; • At least one third (33%) are toxic and may harm or even kill livestock; • Almost all have been commercially available in Australia in the last 20 years; • Over two thirds (70%) were still available from Australian nurseries in 2004; • Over two thirds (72%) are not currently recognised as weeds under either State or Commonwealth legislation. -

The Plant List

the list A Companion to the Choosing the Right Plants Natural Lawn & Garden Guide a better way to beautiful www.savingwater.org Waterwise garden by Stacie Crooks Discover a better way to beautiful! his plant list is a new companion to Choosing the The list on the following pages contains just some of the Right Plants, one of the Natural Lawn & Garden many plants that can be happy here in the temperate Pacific T Guides produced by the Saving Water Partnership Northwest, organized by several key themes. A number of (see the back panel to request your free copy). These guides these plants are Great Plant Picks ( ) selections, chosen will help you garden in balance with nature, so you can enjoy because they are vigorous and easy to grow in Northwest a beautiful yard that’s healthy, easy to maintain and good for gardens, while offering reasonable resistance to pests and the environment. diseases, as well as other attributes. (For details about the GPP program and to find additional reference materials, When choosing plants, we often think about factors refer to Resources & Credits on page 12.) like size, shape, foliage and flower color. But the most important consideration should be whether a site provides Remember, this plant list is just a starting point. The more the conditions a specific plant needs to thrive. Soil type, information you have about your garden’s conditions and drainage, sun and shade—all affect a plant’s health and, as a particular plant’s needs before you purchase a plant, the a result, its appearance and maintenance needs. -

Field Guide for Managing Russian Olive in the Southwest

United States Department of Agriculture Field Guide for Managing Russian Olive in the Southwest Forest Southwestern Service Region TP-R3-16-24 September 2014 Cover Photos Top left: Paul Wray, Iowa State University, Bugwood.org Top right: J. S. Peterson, USDA-NRCS Plants Database Bottom: USDA-NRCS Plants Database The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its programs and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, age, disability, and where applicable, sex, marital status, familial status, parental status, religion, sexual orientation, genetic information, political beliefs, reprisal, or because all or part of an individual’s income is derived from any public assistance program. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.) Persons with disabilities who require alternative means for communication of program information (Braille, large print, audiotape, etc.) should contact USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TTY). To file a complaint of discrimination, write to USDA, Director, Office of Civil Rights, 1400 Independence Avenue, SW, Washington, DC 20250-9410 or call (800) 795-3272 (voice) or (202) 720-6382 (TTY). USDA is an equal opportunity provider and employer. Printed on recycled paper Russian olive (Elaeagnus angustifolia L.) Oleaster family (Elaeagnaceae) Russian olive is widespread throughout the United States • Clusters of small, hard, olive-like, yellowish to red- as a tree and is listed as a noxious weed in New Mexico. brown fruits (drupes, 0.5 inch long) with a dusting of This field guide serves as the U.S. Forest Service’s silver scales; fruit matures August to October. recommendations for management of Russian olive in • Reproduces primarily by seed, although sprouting forests, woodlands, and rangelands associated with its from buds at the root crown and suckers from lateral Southwestern Region. -

Elaeagnus Angustifolia - Russian Olive (Elaeagnaceae) ------Russian-Olive, Oleaster, Or Narrow-Leafed Oleaster Is Twigs Grown for Its Silvery Gray Foliage

Elaeagnus angustifolia - Russian Olive (Elaeagnaceae) ------------------------------------------------------------- Russian-olive, oleaster, or narrow-leafed oleaster is Twigs grown for its silvery gray foliage. The tree prefers a -young branches thin, silvery sunny location and is tolerant of most soil types, but -stems sometimes thorny, covered in scales can be affected by various diseases. It has become a -older branches develop a shiny light brown color problem invasive plant in some areas. -buds are small, silvery-brown and rounded, covered with 4 scales FEATURES Trunk Form grayish-brown older bark -a deciduous large shrub or tree, 20' tall x 20' USAGE spread Function - over 15' tall and wide- -used as a hedge or screen, but may be an accent plant spreading in the border or entranceway because of silvery foliage -rounded habit -may be a foundation shrub -fast growth rate (12-18" -can be massed along highways or seacoasts per year) Texture Culture -fine to medium texture -very adaptable to a wide range of environmental Assets conditions; thrives in alkaline soils and in sandy flood -silvery foliage plains -adaptability and growth in poor sites -able to fix nitrogen so can grow on very poor soils Liabilities -tolerates cold, drought, salt sprays -from a landscape perspective: Canker, Verticillium -easily transplanted wilt and leaf spot destroy that silvery silhouette by -grows most vigorously in full sun killing many branches -does not do well in wet sites or -thorns may be present under dense shade -from an environmental perspective: troublesome -susceptible to foliar and stem invasive that creates heavy shade and suppresses diseases, but affected by few pests plants that require direct sunlight in areas such as -it may invade grasslands and fields, prairies, open woodlands and forest edges. -

Invasive Plant Control Autumn Olive – Elaeagnus Umbellata Conservation Practice Job Sheet NH-595

Pest Management – Invasive Plant Control Autumn Olive – Elaeagnus umbellata Conservation Practice Job Sheet NH-595 Autumn Olive (Elaeagnus umbellata) Autumn Olive, leaves Autumn Olive Autumn olive is native to eastern Asia and was Description introduced to the United States for ornamental Autumn olive is a large deciduous shrub that can grow cultivation in the 1800s. It now grows in most up to 20 feet tall. Leaves are alternately arranged, northeastern and upper Midwest states. elliptic to lanceolate (shaped like a lance head), and smooth-edged. Mature leaves have a dense covering Autumn olive grows well on a variety of soils of lustrous silvery scales on the lower surface. Stems including sandy, loamy, and somewhat clayey textures and buds also have silvery scales. Flowers are small, with a pH range of 4.8-6.5. It does not grow as well creamy white to yellow and tubular in shape; they on very wet or dry sites, but is tolerant to drought. It grow in small clusters. The abundant fruits look like does well on infertile soils because its root nodules small pink berries, also with silvery scales. house nitrogen-fixing actinomycetes. Mature trees tolerate light shade, but produce more fruits in full Similar Natives sun, and seedlings may be shade intolerant. Autumn olive has no similar native plants, but is easily confused with Russian olive, which is a less In New England, autumn olive has escaped from common invader. Unlike autumn olive, Russian olive cultivation and is progressively invading natural areas. often has stiff peg-like thorns, and has silvery scales It is a threat to open and semi-open areas.