Promoting Ecotourism in Himachal Pradesh

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Barot Valley

HIMALAYAN CAMP BAROT VALLEY The programme at Barot is specially develop for the adventure loving youngsters who had been to different parts of the Himalayas but missed the most beautiful part of it. Barot is situated 40 km from Joginder Nagar in a small V-Shaped valley formed by the Uhl river. Surrounded on both sides by Dhauladhar range of the Himalayas, Barot is located at an elevation of 6200 ft above the mean sea level. Across the river Uhl is the Nargu Wildlife Sanctuary, home to Ghoral, Himalayan Black Bear and a variety of pheasants. Forest around Barot is of Deodar and Himalayan Oak. ACTIVITIES: Trekking (between 6,000 ft. to 9,000 ft.), bird watching, rock climbing(jumaring), rappelling, Tyrolean traverse, camp fire, games, etc. ACCOMMODATION: Tents separate for girls & boys. Separate constructed Toilets for girls & boys. FOOD: Wholesome and hygienic vegetarian food will be served thrice a day. ELIGIBILITY: For students of age group 11 – 22 years only. BATCH DATE: 1. 29/04/14 (TUE) TO 06/05/14 (TUE) 2. 05/05/14 (MON) TO 12/05/14 (MON) 3. 13/05/14 (TUE) TO 20/05/14 (TUE) CAMP CHARGES: Rs.8250/- for students (11 to 22yrs.) & Rs.9850/- for others our fees is inclusive of travelling (by different modes), food, activity charges, service charges. REGISTRATION: For registration fill up the application form and pay the fees. Booking will be done on first come first served basis. Cancellation: Minimum: 10% Between 14 & 8 days 50% Between 30 to 15 days 25% Last 7 days No refund Cancellation charges will be applicable on total programme cost. -

DISTT. BILASPUR Sr.No. Name of the Schools DISTRICT

DISTT. BILASPUR Sr.No. Name of the Schools DISTRICT The Principal, Govt. Sr. Secondary School Bharari, Teh. Ghumarwain, P.O BILASPUR 1 Bharari, Distt. Bilaspur. H.P Pin: 174027 The Principal, Govt. Sr. Secondary School Dangar, Teh. Ghumarwain, BILASPUR 2 P.O. Dangar,Distt. Bilaspur. H.P Pin: 174025 The Principal,Govt. Senior Secondary School,Ghumarwin, Tehsil BILASPUR 3 Ghumarwin, P.O.District Bilaspur,Himachal Pradesh, Pin-174021 The Principal,Govt. Senior Secondary School,Hatwar, Tehsil Ghumarwin, BILASPUR 4 P.O. Hatwar, District Bilaspur,Himachal Pradesh, Pin-174028 The Principal,Govt. Senior Secondary School,Kuthera, Tehsil Ghumarwin, BILASPUR 5 P.O. Kuthera,District Bilaspur,Himachal Pradesh, Pin-174026 The Principal,Govt. Senior Secondary School Morsinghi, Tehsil BILASPUR 6 Ghumarwin, P.O.Morsinghi,District Bilaspur, H.P. 174026 The Principal,Govt. Senior Secondary School,Chalhli, Tehsil Ghumarwin, BILASPUR 7 P.O. Chalhli, District Bilaspur,H. P, Pin-174026 The Principal, Govt. Senior Secondary School,Talyana,,Teh Ghumarwin, BILASPUR 8 P.O. Talyana,District Bilaspur,H. P, Pin-174026 The Principal, Govt. Senior Secondary School, Berthin Tehsil Jhandutta, BILASPUR 9 P.O. Berthin District Bilaspur,H. P. Pin-174029 The Principal, Govt. Senior Secondary School, Geherwin, Teh Jhandutta, BILASPUR 10 P.O. GehrwinDistrict Bilaspur, H. P. Pin- The Principal, Govt. Senior Secondary School,Jhandutta, Tehsil Jhandutta, BILASPUR 11 P.O.Jhandutta, District Bilaspur, H. P Pin-174031 The Principal,Govt. Senior Secondary School,Jejwin, P.O.District Bilaspur, BILASPUR 12 Himachal Pradesh, Pin- The Principal, Govt. Senior Secondary School,Koserian, Tehsil Jhandutta, BILASPUR 13 P.O. Kosnria,District Bilaspur, H. P. Pin-174030 The Principal, Govt. -

Kangra, Himachal Pradesh

` SURVEY DOCUMENT STUDY ON THE DRAINAGE SYSTEM, MINERAL POTENTIAL AND FEASIBILITY OF MINING IN RIVER/ STREAM BEDS OF DISTRICT KANGRA, HIMACHAL PRADESH. Prepared By: Atul Kumar Sharma. Asstt. Geologist. Geological Wing” Directorate of Industries Udyog Bhawan, Bemloe, Shimla. “ STUDY ON THE DRAINAGE SYSTEM, MINERAL POTENTIAL AND FEASIBILITY OF MINING IN RIVER/ STREAM BEDS OF DISTRICT KANGRA, HIMACHAL PRADESH. 1) INTRODUCTION: In pursuance of point 9.2 (Strategy 2) of “River/Stream Bed Mining Policy Guidelines for the State of Himachal Pradesh, 2004” was framed and notiofied vide notification No.- Ind-II (E)2-1/2001 dated 28.2.2004 and subsequently new mineral policy 2013 has been framed. Now the Minstry of Environemnt, Forest and Climate Change, Govt. of India vide notifications dated 15.1.2016, caluse 7(iii) pertains to preparation of Distt Survey report for sand mining or riverbed mining and mining of other minor minerals for regulation and control of mining operation, a survey document of existing River/Stream bed mining in each district is to be undertaken. In the said policy guidelines, it was provided that District level river/stream bed mining action plan shall be based on a survey document of the existing river/stream bed mining in each district and also to assess its direct and indirect benefits and identification of the potential threats to the individual rivers/streams in the State. This survey shall contain:- a) District wise detail of Rivers/Streams/Khallas; and b) District wise details of existing mining leases/ contracts in river/stream/khalla beds Based on this survey, the action plan shall divide the rivers/stream of the State into the following two categories;- a) Rivers/ Streams or the River/Stream sections selected for extraction of minor minerals b) Rivers/ Streams or the River/Stream sections prohibited for extraction of minor minerals. -

WETLANDS of Himachal Pradesh Himachal Pradesh State Wetland Authority WETLANDS

Major WETLANDS Of Himachal Pradesh Himachal Pradesh State Wetland Authority WETLANDS Wetlands are important features in the landscape that provide numerous benecial services for people, wildlife and aquatic species. Some of these services, or functions, include protecting and improving water quality, providing sh and wildlife habitats, storing oodwaters and maintaining surface water ow during dry periods. These valuable functions are the result of the unique natural characteristics of wetlands. Wetlands are among the most productive ecosystems in the world, comparable to rain forests and coral reefs. An immense variety of WETLANDS species of microbes, plants, insects, amphibians, Conservation Programme with the active reptiles, birds, sh and mammals can be part of a participation of all the stakeholders, keeping in view wetland ecosystem. Climate, landscape shape the requirement of multidisciplinary approach, (topology), geology and the movement and various Departments and Agencies such as Forests, abundance of water help to determine the plants Fisheries, Tourism, Industries, HP Environment and animals that inhabit each wetland. The complex, Protection and Pollution Control Board, dynamic relationships among the organisms Universities, Zoological Survey of India. National & inhabiting the wetland environment are called food State level research institutes are also actively webs. Wetlands can be thought of as "biological involved in the Wetland Conservation Programme. supermarkets." The core objective of the Ramsar convention dened Wetland Conservation Programme is to conserve wetlands as areas of marsh, fen, peat land or water, and restore wetlands with the active participation of whether natural or articial, permanent or t h e l o c a l c o m m u n i t y a t t h e p l a n n i n g , temporary, with water that is static or owing, fresh, implementation and monitoring level. -

Proforma for Annual Report 2014-15

PROFORMA FOR ANNUAL REPORT 2014-15 1. GENERAL INFORMATION ABOUT THE KVK 1.1. Name and address of KVK with phone, fax and e-mail Address Telephone E mail Office FAX KVK Kullu at Bajaura District Kullu 175 125 HP 01905-287318 01905-287318 [email protected] 1.2 .Name and address of host organization with phone, fax and e-mail Address Telephone E mail Office FAX CSK HPKV Palampur 176 062 HP 01894-230383 01894-230511 [email protected] 1.3. Name of the Programme Coordinator with phone, mobile No & e-mail Name Telephone / Contact Residence Mobile Email Dr. Surender Kumar Thakur 9418193270 9418193270 [email protected] 1.4. Year of sanction: 1985 st 1.5. Staff Position (as on 31 March 2015) Pay Band Category Discipline Present Date of Sl. Name of the & Grade Permanent (SC/ST/ Sanctioned post Age with highest basic joining in No. incumbent Pay (Rs.) /Temporary OBC/ degree obt. (Rs.) KVK Others) 1 Programme Dr Surender 46 Soil Science, 37400- 44820 01.11.2013 Temporary Others Coordinator Kumar Thakur Ph.D. 67000 (GP 9000) 2 Subject Matter Dr (Mrs.) 47 Food and 37400- 53610 04.07.1994 Permanent Others Specialist Chanderkanta Nutrition, 67000 Ph.D. (GP 10000) 3 Subject Matter Dr K C Sharma 51 Vegetable 37400- 51750 04.11.2009 Permanent Others Specialist Science, 67000 Ph.D. (GP 10000) 4 Subject Matter Dr Ramesh Lal 43 Entomology, 15600- 23080 20.10.2007 Temporary SC Specialist Ph.D. 39100 (GP 6000) 5 Subject Matter Dr (Mrs.) 38 Vety. 15600- 21390 07.04.2006 Temporary Others Specialist Deepali Kapoor Parasitology, 39100 M.V.Sc. -

List PWD Rest Houses – Himachal Pradesh

http://devilonwheels.com List of Rest Houses & Circuit Houses in Himachal Pradesh Approx. Distance Rest House/Circuit House STD Phone PWD Division/ Booking Office E-Mail ID from Booking No. of Suites Location Code Number Office(in kms) Lahaul & Spiti New Circuit House at Kaza E.E. Kaza /A.D.C. office Kaza 1906 222252 [email protected] 1.5 10 Old Circuit House at Kaza E.E. Kaza /A.D.C. office Kaza 1906 222252 [email protected] 1 4 Class-III Rest House at Kaza E.E. Kaza /A.D.C. office Kaza 1906 222252 [email protected] 0.5 3 Old Rest House at Lossar E.E. kaza /A.D.C. office Kaza 1906 222252 [email protected] 56 2 New Rest House at Lossar E.E. Kaza /A.D.C. office Kaza 1906 222252 [email protected] 56 3 Rest House at Pangmo E.E. Kaza /A.D.C. office Kaza 1906 222252 [email protected] 24 3 Old Rest House at Sagnam E.E. Kaza /A.D.C. office Kaza 1906 222252 [email protected] 40 2 New Rest House at Sagnam E.E. Kaza /A.D.C. office Kaza 1906 222252 [email protected] 40 4 Rest House at Tabo E.E. Kaza /A.D.C. office Kaza 1906 222252 [email protected] 47 5 Rest House at Lari E.E. Kaza /A.D.C. office Kaza 1906 222252 [email protected] 50 3 Rest House at Sumdo E.E. Kaza /A.D.C. -

Guru Padmasambhava and His Five Main Consorts Distinct Identity of Christianity and Islam

Journal of Acharaya Narendra Dev Research Institute l ISSN : 0976-3287 l Vol-27 (Jan 2019-Jun 2019) Guru Padmasambhava and his five main Consorts distinct identity of Christianity and Islam. According to them salvation is possible only if you accept the Guru Padmasambhava and his five main Consorts authority of their prophet and holy book. Conversely, Hinduism does not have a prophet or a holy book and does not claim that one can achieve self-realisation through only the Hindu way. Open-mindedness and simultaneous existence of various schools Heena Thakur*, Dr. Konchok Tashi** have been the hall mark of Indian thought. -------------Hindi----cultural ties with these countries. We are so influenced by western thought that we created religions where none existed. Today Abstract Hinduism, Buddhism and Jaininism are treated as Separate religions when they are actually different ways to achieve self-realisation. We need to disengage ourselves with the western world. We shall not let our culture to This work is based on the selected biographies of Guru Padmasambhava, a well known Indian Tantric stand like an accused in an alien court to be tried under alien law. We shall not compare ourselves point by point master who played a very important role in spreading Buddhism in Tibet and the Himalayan regions. He is with some western ideal, in order to feel either shame or pride ---we do not wish to have to prove to any one regarded as a Second Buddha in the Himalayan region, especially in Tibet. He was the one who revealed whether we are good or bad, civilised or savage (world ----- that we are ourselves is all we wish to feel it for all Vajrayana teachings to the world. -

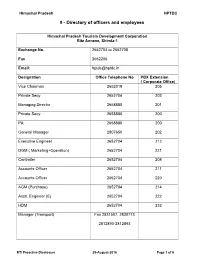

9 - Directory of Officers and Employees

Himachal Pradesh HPTDC 9 - Directory of officers and employees Himachal Pradesh Tourism Development Corporation Ritz Annexe, Shimla-1 Exchange No. 2652704 to 2652708 Fax 2652206 Email: [email protected] Designation Office Telephone No PBX Extension ( Corporate Office) Vice Chairman 2652019 205 Private Secy 2652704 203 Managing Director 2658880 201 Private Secy 2658880 200 PA 2658880 200 General Manager 2807650 202 Executive Engineer 2652704 212 DGM ( Marketing+Operation) 2652704 221 Controller 2652704 208 Accounts Officer 2652704 211 Accounts Officer 2652704 220 AGM (Purchase) 2652704 214 Asstt. Engineer (E) 2652704 222 HDM 2652704 232 Manager (Transport) Fax 2831507, 2830713 2812890-2812893 RTI Proactive Disclosure 29-August-2016 Page 1 of 6 Himachal Pradesh HPTDC Designation Office Telephone No HOLIDAY HOME COMPLEX Dy GM 2656035 Sr.Manager (Peterhof) 2812236 Fax-2813801 Asstt. Mgr. Apple C.InnKiarighat 01792-208148 Incharge, Hotel Bhagal 01796-248116, 248117 Asstt. Mgr. Golf Glade, Naldehra 2747809, 2747739 Incharge, HtlMamleshwar, Chindi 01907- 222638 Sr. Manager, Apple Blossom, Fagu 01783-239469 Incharge. Lift (HPTDC) 2807609 CHAMBA-DALHOUSIE COMPLEX Sr. Manager, Marketing Office 1899242136 Sr.Manager,HotelIravati 01899-222671 Incharge, Hotel Deodar, Khajjiar 01899-236333 Incharge, Hotel Geetanjli, Dalhousie 01899-242155 The Manimahesh, Dalhousie 01899-242793, 242736 DHARAMSHALA COMPLEX AGM, Mkt. Office 01892-224928, 224212 AGM, Dhauladhar 01892-224926, 223456 Asstt. Manager, Kashmir House 01892-222977 Sr.Manager, Hotel Bhagsu 01892-221091 Asstt. Manager, Hotel Kunal 01892-223163, 222460 Designation Office Telephone No RTI Proactive Disclosure 29-August-2016 Page 2 of 6 Himachal Pradesh HPTDC Asstt. Manager,Club House 01892-220834 Asstt. Manager, Yatri Niwas, Chamunda 01892-236065 Incharge, The Chintpurni Height 01976-255234 JAWALAJI COMPLEX Asstt. -

Lok Mitra Kendras (Lmks)

DistrictName BlockName Panchayat Village VLEName LMKAddress ContactNo Name Name Chamba Bharmour BHARMOUR bharmour MADHU BHARMOUR 8894680673 SHARMA Chamba Bharmour CHANHOTA CHANHOTA Rajinder Kumar CHANHOTA 9805445333 Chamba Bharmour GAROLA GAROLA MEENA KUMARI GAROLA 8894523608 Chamba Bharmour GHARED Ghared madan lal Ghared 8894523719 Chamba Bharmour GREEMA FANAR KULDEEP SINGH GREEMA 9816485211 Chamba Bharmour HOLI BANOON PINU RAM BANOON 9816638266 Chamba Bharmour LAMU LAMU ANIL KUMAR LAMU 8894491997 Chamba Bharmour POOLAN SIRDI MED SINGH POOLAN 9816923781 Chamba Bharmour SACHUIN BARI VANDANA SACHUIN 9805235660 Chamba Bhattiyat NULL Chowari SANJAY Chowari 9418019666 KAUSHAL Chamba Bhattiyat NULL DEEPAK RAJ Village Kathlage 9882275806 PO Dalhausie Tehsil Dalhausie Distt Chamba Chamba Bhattiyat AWHAN Hunera Sanjeet Kumar AWHAN 9816779541 Sharma Chamba Bhattiyat BALANA BALANA RAM PRASHAD 9805369340 Chamba Bhattiyat BALERA Kutt Reena BALERA 9318853080 Chamba Bhattiyat BANET gaherna neelam kumari BANET 9459062405 Chamba Bhattiyat BANIKHET BANIKHET NITIN PAL BANIKET 9418085850 Chamba Bhattiyat BATHRI BATHRI Parveen Kumar BATHRI 9418324149 Chamba Bhattiyat BINNA chhardhani jeewan kumar BINNA 9418611493 Chamba Bhattiyat CHUHAN Garh (Bassa) Ravinder Singh CHUHAN 9418411276 Chamba Bhattiyat GAHAR GAHAR SHASHI GAHAR 9816430100 CHAMBIAL Chamba Bhattiyat GHATASANI GHATASANI SHEETAL GHATASANI 9418045327 Chamba Bhattiyat GOLA gola santosh GOLA 9625924200 Chamba Bhattiyat JIYUNTA kunha kewal krishan JIYUNTA 9418309900 Chamba Bhattiyat JOLNA Jolna Meena -

(A) Appellate Authorities

HIMACHAL PRADESH Public Works Department Himachal Pradesh Public Works Deaprtment Notification In supersession of this office Notification No:- PW-ROIA/WS- 534-763, dated 11-10-2005 and this office further order No. PW(B)-RTI Act 2005/WS-8745-8820, dated 07-11-2006. I, The Engineer-in-Chief HP, PWD in exercise of the powers conferred upon me under sub-section (1) and (2) of section-5 of the RTI Act,05 re-designate the following officers of the Himachal Pradesh Public Works Department as appellate Authorities, Public Information Officers and Asstt. Public Information Officers with immediate effect in the public interest, (A) Appellate Authorities Sr. Designation Of Authority States under the Act Telephone No No Office Residence 1. Superintending Engineer For O/O E-in-C, HP, PWD, Shimla-2, 2625821 2626426 (Works) O/OE-in-C, HP, O/O Chief Engineer (South) HP,PWD, PWD, Nigam Vihar, Shimla-2 and for O/O Land Acquisition Shimla- 171 002. Officer, HP, PWD, Winter Field, Shimla-3. 2. Superintending Engineer For O/O E-in-C (Q.C.) Office, HP, 2652438 2622914 (Q.C.&D) O/O E-in-C(Q.C.) PWD,U.S.Club, Shimla-1. Office, HP, PWD,U.S.Club, Shimla-1. 3 Superintending Engineer For O/O Chief Engineer(CZ) HP, PWD, 221621 221154 (Works) O/O Chief Engineer Mandi and for O/O Land Acquisition (CZ) HP, PWD, Mandi. Officer, HP, PWD, Mandi. 4 Superintending Engineer For O/O Chief Engineer (NZ) office 223189 226264 (Works) O/O Chief Engineer HP,PWD, Dharamshala and for O/O (NZ) HP,PWD,Dharamshala. -

Parvati Valley, Kheerganga Trek, Tosh Trek, Malana Trek, Chalala Village Trek (Himachal Adventure Tour) - 3 Nights / 4 Days

Parvati Valley, Kheerganga Trek, Tosh Trek, Malana Trek, Chalala Village Trek (Himachal Adventure Tour) - 3 Nights / 4 Days Free: 1800 11 2277 | [email protected]|www.zenithholidays.com Ahmedabad: 079-45120000 | Bangalore: 080-42420500-0525 |Chandigarh: 91 9988892300 | Chennai: 044-49040000 Delhi: 011-45120000 | Hyderabad: 040-49094000 | Kolkata: 033-40143918-21| Mumbai: 022-40369000-22 | Pune: 020-26057101/2/3 Holidays | Insurance | Honeymoon | Off sites | Visa | Reward Programs | Ticketing | Worldwide Hotels | Forex | Weddings Features Includes Transfers Sightseeings Hotels Overview Himachal Pradesh stands for – the magnanimous Himalayas, the holiest of the rivers, the spiritual mystery, stunning landscapes, the incessantly colorful play of nature, enchanting history carved in ancient stones, a mesmerizing floral and faunal plethora and the simplest of the people. Myths, anecdotes and stories are part of every visual that unfolds itself to the eyes of the beholder. Parvati Valley is without doubt hotspot of leisure stay and beautiful landscapes and is very famous by name of Amsterdam of India. It is said that Lord Shiva meditated in this valley for about more than 3,000 years. He is believed to have taken the form of a naga sadhu.You will fall short of fall short of words to describe the beauty, peace, serenity and tranquillity of the place in Parvati Valley like Kasol, Tosh, Kheerganga and Chalal Village. Itinerary Details Day-1 Car: Sightseeing: Hotels Transfer from Bhuntar - to - Kasol Hotel Camp / Tents / Parvati Valley - Malana -

Water Quality and Phytoplankton Diversity of High Altitude Wetland, Dodi Tal of Garhwal Himalaya, India

Biodiversity International Journal Research Article Open Access Water quality and phytoplankton diversity of high altitude wetland, Dodi Tal of Garhwal Himalaya, India Abstract Volume 2 Issue 6 - 2018 Water quality and phytoplankton diversity of high altitude (3,075 above m.a.s.l.) wetland Ramesh C Sharma, Sushma Singh Dodi Tal were monitored for a period of November 2015 to October 2016. A total of 47 species Department of Environmental Sciences, Hemvati Nandan belonging to 43 genera of four families (Bacillariophyceae; Chlorophyceae; Cyanophyceae; Bahughuna Garhwal University, India Dinophyceae) of phytoplankton were encounted during the study. Bacillariophyceae was the dominant family representing 20 genera followed by Chlorophyceae (16 genera), Correspondence: Sushma Singh, Department of Cyanophyceae (4 genera) and Dinophyceae (3 genera). A highly significant (F=14.59; Environmental Sciences, Hemvati Nandan Bahughuna Garhwal p=1.43E-08) seasonal variation in the abundance of phytoplankton community of Dodi University, (A Central University) Srinagar, Garhwal, 246174, Tal was recorded. Maximum abundance of phytoplankton (1,270±315.00ind.l-1) was Uttarakhand, India, Email [email protected] found in autumn season and minimum (433.00±75.00ind.l-1) in monsoon season. Multiple regression analysis made between density of phytoplankton and environmental variables Received: July 31, 2018 | Published: November 05, 2018 revealed that the abundance of phytoplankton has a negative correlation with TDS, alkalinity, dissolved oxygen, pH and Chlorides. However, it has a positive correlation with water temperature phosphates and nitrates. Shannon Wiener diversity index was recorded maximum (4.09) in autumn season and minimum (3.59) in monsoon season. Canonical Correspondence Analysis (CCA) was also calculated between physico-chemical variables and phytoplankton diversity for assessing the effect of physico- chemical variables on various taxa of phytoplankton.