Instructed Eucharist

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE EPISTLE St

THE EPISTLE St. Philip’s Episcopal Church 342 East Wood Street Palatine, Illinois 60067-5357 (847) 358-0615 www.stphilipspalatine.org http://www.facebook.com/stphilipspalatine The Rev. Jim Stanley, Rector Dear friend in Christ, What does your faith in Jesus mean to you? Has your Christian faith seen you through some tough times? Does the knowledge that you are "sealed by the Holy Spirit in Baptism and marked as Christ's own forever" (BCP p. 308) bring you hope and comfort for your future? Have there been times when a particular passage of Scripture has lifted you? I'm sure most people reading this know exactly what I mean. I don't want us to simply stop with being grateful for our faith. Be thankful, yes; but the same Lord who has so comforted and encouraged us, has also urged us to serve others. Jesus expects us to work for justice and peace. We are to feed the hungry, advocate for the poor, comfort the widow and orphan. May we never lose sight of this Great Commandment to do to others as we would have done to ourselves! In addition to leaving us with a Great Commandment, our Lord also assigned us a Great Commission. Just before He ascended to His Father in Heaven, Jesus told His disciples -- 1 and by extension, all who would come to believe in Him in the future -- to "Go into all the world and proclaim His Good News, making disciples of all nations and baptizing in the Name of the Holy Trinity." Jesus ordered that His message be taken "to the uttermost parts of the earth". -

Stand Priest: in the Name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy

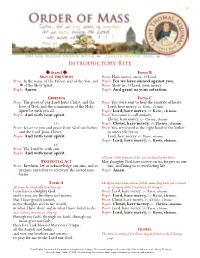

1 Stand Form B SIGN OF THE CROSS Priest: Have mercy on us, O Lord. Priest: In the name of the Father, and of the Son, and People: For we have sinned against you. ✠of the Holy Spirit. Priest: Show us, O Lord, your mercy. People: Amen. People: And grant us your salvation. GREETING Form C Priest: The grace of our Lord Jesus Christ, and the Priest: You were sent to heal the contrite of heart: love of God, and the communion of the Holy Lord, have mercy. Or: Kyrie, eleison. Spirit be with you all. People: Lord, have mercy. Or: Kyrie, eleison. People: And with your spirit. Priest: You came to call sinners: Christ, have mercy. Or: Christe, eleison. Or: People: Christ, have mercy. Or: Christe, eleison. Priest: Grace to you and peace from God our Father Priest: You are seated at the right hand of the Father and the Lord Jesus Christ. to intercede for us: People: And with your spirit. Lord, have mercy. Or: Kyrie, eleison. People: Lord, have mercy. Or: Kyrie, eleison. Or: Priest: The Lord be with you. People: And with your spirit. All forms of the Penitential Act are concluded by the Priest: PENITENTIAL ACT May almighty God have mercy on us, forgive us our Priest: Brethren, let us acknowledge our sins, and so sins, and bring us to everlasting life. prepare ourselves to celebrate the sacred mys- People: Amen. teries. Form A The Kyrie eleison invocations follow, unless they have just occurred All pause for silent reflection then say: in a formula of the Penitential Act (Form C). -

SAINT BASIL the GREAT ALTAR SERVER MANUAL Prayers of An

SAINT BASIL THE GREAT ALTAR SERVER MANUAL Prayers of an Altar Server O God, You have graciously called me to serve You upon Your altar. Grant me the graces that I need to serve You faithfully and wholeheartedly. Grant too that while serving You, may I follow the example of St. Tarcisius, who died protecting the Eucharist, and walk the same path that led him to Heaven. St. Tarcisius, pray for me and for all servers. ALTAR SERVER'S PRAYER Loving Father, Creator of the universe, You call Your people to worship, to be with You and each other at Mass. Help me, for You have called me also. Keep me prayerful and alert. Help me to help others in prayer. Thank you for the trust You've placed in me. Keep me true to that trust. I make my prayer in Jesus' name, who is with us in the Holy Spirit. Amen. 1 PLEASE SIGN AND RETURN THIS TOP SHEET IMMEDIATELY To the Parent/ Guardian of ______________________________(server): Thank you for supporting your child in volunteering for this very important job as an Altar Server. Being an Altar Server is a great honor – and a responsibility. Servers are responsible for: a) knowing when they are scheduled to serve, and b) finding their own coverage if they cannot attend. (email can help) The schedule is emailed out, prior to when it begins. The schedule is available on the Church website, and published the week before in the Church Bulletin. We have attached the, “St. Basil Altar Server Manual.” After your child attends the two server training sessions, he/she will most likely still feel unsure about the job – that’s OK. -

The Rites of Holy Week

THE RITES OF HOLY WEEK • CEREMONIES • PREPARATIONS • MUSIC • COMMENTARY By FREDERICK R. McMANUS Priest of the Archdiocese of Boston 1956 SAINT ANTHONY GUILD PRESS PATERSON, NEW JERSEY Copyright, 1956, by Frederick R. McManus Nihil obstat ALFRED R. JULIEN, J.C. D. Censor Lib1·or111n Imprimatur t RICHARD J. CUSHING A1·chbishop of Boston Boston, February 16, 1956 PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA INTRODUCTION ANCTITY is the purpose of the "new Holy Week." The news S accounts have been concerned with the radical changes, the upset of traditional practices, and the technical details of the re stored Holy Week services, but the real issue in the reform is the development of true holiness in the members of Christ's Church. This is the expectation of Pope Pius XII, as expressed personally by him. It is insisted upon repeatedly in the official language of the new laws - the goal is simple: that the faithful may take part in the most sacred week of the year "more easily, more devoutly, and more fruitfully." Certainly the changes now commanded ,by the Apostolic See are extraordinary, particularly since they come after nearly four centuries of little liturgical development. This is especially true of the different times set for the principal services. On Holy Thursday the solemn evening Mass now becomes a clearer and more evident memorial of the Last Supper of the Lord on the night before He suffered. On Good Friday, when Holy Mass is not offered, the liturgical service is placed at three o'clock in the afternoon, or later, since three o'clock is the "ninth hour" of the Gospel accounts of our Lord's Crucifixion. -

Mass Coordinator Checklist for the Historic Church Before Mass • Arrive at Least 30 Minutes Prior to the Start of Mass

MC Checklist for the Historic Church October 2013 Mass Coordinator Checklist for the Historic Church Before Mass • Arrive at least 30 minutes prior to the start of Mass. • Take down the chain across the parking lot. • Unlock door of church. • Turn on interior lights and any appropriate exterior lights. • For a weekend Mass check the MC/Greeter/Usher notes (found on the Offertory table - cabinet behind pews on the left side of aisle) for any updates or changes for that Mass. • Turn the sound system on (located in the wooden cabinet in the Adoration Room). The button on the right of each box needs to be pushed in. You will know if they are both on if they turn green. Note that the button on the smaller device on top has to be pushed in for a few seconds before it turns green. • To check if they are both on properly see if the green light is on by the bottom of the microphone on the ambo. Lectionary • Turn on the fans if necessary. The switches for the fan are located in the same cabinet as the sound system. The switch to the left controls the speed of the fan. Fan Placard • Turn the altar and sanctuary lights on (switches are labeled inside the Adoration Room). • Turn the thermostat (by the sacristy door) up to 68 degrees. • For weekend Masses check the Presider’s Schedule to see who is celebrating (taped to the small refrigerator in the sacristy). If Fr. Frazier is not presiding or not has not yet arrived, get the appropriate vestments from the Parish Center and hang on the back of the door of Sacristy. -

Church and Liturgical Objects and Terms

Church and Liturgical Objects and Terms Liturgical Objects Used in Church The chalice: The The paten: The vessel which golden “plate” that holds the wine holds the bread that that becomes the becomes the Sacred Precious Blood of Body of Christ. Christ. The ciborium: A The pyx: golden vessel A small, closing with a lid that is golden vessel that is used for the used to bring the distribution and Blessed Sacrament to reservation of those who cannot Hosts. come to the church. The purificator is The cruets hold the a small wine and the water rectangular cloth that are used at used for wiping Mass. the chalice. The lavabo towel, The lavabo and which the priest pitcher: used for dries his hands after washing the washing them during priest's hands. the Mass. The corporal is a square cloth placed The altar cloth: A on the altar beneath rectangular white the chalice and cloth that covers paten. It is folded so the altar for the as to catch any celebration of particles of the Host Mass. that may accidentally fall The altar A new Paschal candles: Mass candle is prepared must be and blessed every celebrated with year at the Easter natural candles Vigil. This light stands (more than 51% near the altar during bees wax), which the Easter Season signify the and near the presence of baptismal font Christ, our light. during the rest of the year. It may also stand near the casket during the funeral rites. The sanctuary lamp: Bells, rung during A candle, often red, the calling down that burns near the of the Holy Spirit tabernacle when the to consecrate the Blessed Sacrament is bread and wine present there. -

Jesuits and Eucharistic Concelebration

JesuitsJesuits and Eucharistic Concelebration James J. Conn, S.J.S.J. Jesuits,Jesuits, the Ministerial PPriesthood,riesthood, anandd EucharisticEucharistic CConcelebrationoncelebration JohnJohn F. Baldovin,Baldovin, S.J.S.J. 51/151/1 SPRING 2019 THE SEMINAR ON JESUIT SPIRITUALITY Studies in the Spirituality of Jesuits is a publication of the Jesuit Conference of Canada and the United States. The Seminar on Jesuit Spirituality is composed of Jesuits appointed from their provinces. The seminar identifies and studies topics pertaining to the spiritual doctrine and practice of Jesuits, especially US and Canadian Jesuits, and gath- ers current scholarly studies pertaining to the history and ministries of Jesuits throughout the world. It then disseminates the results through this journal. The opinions expressed in Studies are those of the individual authors. The subjects treated in Studies may be of interest also to Jesuits of other regions and to other religious, clergy, and laity. All who find this journal helpful are welcome to access previous issues at: [email protected]/jesuits. CURRENT MEMBERS OF THE SEMINAR Note: Parentheses designate year of entry as a seminar member. Casey C. Beaumier, SJ, is director of the Institute for Advanced Jesuit Studies, Chestnut Hill, Massachusetts. (2016) Brian B. Frain, SJ, is Assistant Professor of Education and Director of the St. Thomas More Center for the Study of Catholic Thought and Culture at Rock- hurst University in Kansas City, Missouri. (2018) Barton T. Geger, SJ, is chair of the seminar and editor of Studies; he is a research scholar at the Institute for Advanced Jesuit Studies and assistant professor of the practice at the School of Theology and Ministry at Boston College. -

What's It Called? Vestments the Vestments Are the Special Clothing Worn by the Clergy and Lay Assistants As They Officiate at the Various Church Services

What’s It Called? A brief explanation of the names and meanings of objects found in the church and used in the Liturgy 1 This little booklet is offered in the hope of enabling the members of this congregation to know and better understand those things we constantly use in worship. The comic name rather belies a serious intent. As inheritors of the liturgical tradition of worship, which employs the use of many objects in the conduct of our solemn worship, it seem only fitting that we should know what those objects are, why they are used (more often for convenience and practicality that any other reason), and their proper names. There are some who think that such knowledge should be avoided, as leading to obfuscation or obscurantism. I disagree. The more we know and understand, the more intelligently and un-distractedly we are able to assist in the worship of Almighty God: Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. Douglas Kornahrens Drawings by Stan Wale 2 What's It Called? vestments The vestments are the special clothing worn by the clergy and lay assistants as they officiate at the various church services. These vestments originated from the everyday dress of citizens of the Roman world in the first few centuries of the life of the church. alb The alb is the basic item of liturgical vesture and is worn by all, both clergy and laity, who participate in the Liturgy. The word comes directly from the Latin alba which means ‘white’. The garment derives from the basic garment of Roman dress which was a long white linen tunic. -

St. Matthew's Church Newport Beach, California

St. Matthew’s Church Newport Beach, California Copyright © The Rt. Rev’d Stephen Scarlett, 2012 Publication Copyright © St. Matthew’s Church & School, 2012 stmatthewsnewport.com ALL RIGHTS RESERVED Cover Image: Caravaggio, Supper at Emmaus, 1606 Brera Fine Arts Academy, Milan TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 9-11 Chapter 1: The Creeds of the Church 13-27 Chapter 2: The Moral Law and the Gospel 29-40 Chapter 3: The Sacraments 41-53 Chapter 4: The Church and Its Symbolism 55-64 Chapter 5: Commentary on the Liturgy of the Holy Communion 65-103 Chapter 6: The Church Calendar 105-110 Chapter 7: The Life of Prayer 111-121 Chapter 8: The Duties of a Christian 123-129 INTRODUCTION HE Inquirers’ Class is designed to provide an introduction to what the church believes and does. TOne goal of the class is to provide space in the church for people who have questions to pursue answers. Another goal is that people who work their way through this material will be able to begin to participate meaningfully in the ministry and prayer life of the church. The Inquirers’ Class is not a Bible study. However, the main biblical truths of the faith are the focus of the class. The Inquirers’ Class gives the foundation and framework for our practice of the faith. If the class has its desired impact, participants will begin the habit of daily Bible reading in the context of daily prayer. The Need for An Inquirer’s Class People who come to the liturgy without any instruction will typically be lost or bored. -

Traditional Latin Mass (TLM), Otherwise Known As the Extraordinary Form, Can Seem Confusing, Uncomfortable, and Even Off-Putting to Some

For many who have grown up in the years following the liturgical changes that followed the Second Vatican Council, the Traditional Latin Mass (TLM), otherwise known as the Extraordinary Form, can seem confusing, uncomfortable, and even off-putting to some. What I hope to do in a series of short columns in the bulletin is to explain the mass, step by step, so that if nothing else, our knowledge of the other half of the Roman Rite of which we are all a part, will increase. Also, it must be stated clearly that I, in no way, place the Extraordinary Form above the Ordinary or vice versa. Both forms of the Roman Rite are valid, beautiful celebrations of the liturgy and as such deserve the support and understanding of all who practice the Roman Rite of the Catholic Church. Before I begin with the actual parts of the mass, there are a few overarching details to cover. The reason the priest faces the same direction as the people when offering the mass is because he is offering the sacrifice on behalf of the congregation. He, as the shepherd, standing in persona Christi (in the person of Christ) leads the congregation towards God and towards heaven. Also, it’s important to note that a vast majority of what is said by the priest is directed towards God, not towards us. When the priest does address us, he turns around to face us. Another thing to point out is that the responses are always done by the server. If there is no server, the priest will say the responses himself. -

Kiss of Peace in the Roman Rite, Antiphon 14/1 (2010), 47

1 Let Christ Give Me a Kiss 1 Sr. Joyce Ann Zimmerman, C.PP.S. Institute for Liturgical Ministry, Dayton, Ohio Only as an older child did I figure out that some of the folks I called “aunt” or “uncle” were not blood relatives at all, but were good friends of my parents whom we saw frequently. Another social convention in our home was that we kissed relatives and these close friends hello and goodbye. And maybe that’s why I considered the non-relatives part of the family: a warm, caring, secure relationship was evident from both relatives and close friends. This is what a kiss came to mean to me: a warm and welcome relationship. A kiss is an exchange between two persons, indicative of some kind of a relationship. Although much of society and the entertainment media limit the meaning of kissing to an erotic relationship, its meaning in times past and now includes more than sexual intimacy. If we are to have any understanding at all of a liturgical use of kissing, we must delve into the richness this gesture connotes. Universal Gesture, Many Meanings Kissing in one form or another seems to be a fairly universal gesture—but not always with the same meaning. Used more in the West than in the East, the Romans actually had three different Latin words for “kiss.” 2 Basium is a kiss between acquaintances, possibly linked to the Latin basis meaning foundation or basic. A kiss would be given as a social custom and perhaps used to seal an agreement. -

Saint John the Apostle Catholic Parish and School Altar Server Handbook

Saint John the Apostle Catholic Parish and School Altar Server Handbook February 2017 Table of Contents Chapter 1 – What is an Altar Server Page 3 Chapter 2 – Server Duties Page 5 Chapter 3 – The Mass Page 7 Chapter 4 – Baptism within the Mass Page 13 Chapter 5 – Nuptial Mass (Weddings) Page 14 Chapter 6 – Funeral Mass Page 15 Chapter 7 – Benediction Page 19 Chapter 8 – Stations of the Cross Page 20 Chapter 9 – Incense feasts Page 21 Chapter 10 – Miter and Crozier Page 22 Chapter 11 – Church Articles Page 24 2 Chapter 1 What is an Altar Server? An altar server is a lay assistant to a member of the clergy during a religious service. An altar server attends to supporting tasks at the altar such as fetching and carrying, ringing bells, setting up, cleaning up, and so on. Until 1983, only young men whom the Church sometimes hoped to recruit for the priesthood and seminarians could serve at the altar, and thus altar boy was the usual term until Canon 230 was changed in the 1983 update to the Code of Canon which provided the option for local ordinaries (bishops) to permit females to serve at the altar. The term altar server is now widely used and accepted. When altar servers were only young men and seminarians the term acolyte was used. An acolyte is one of the instituted orders which is installed by a bishop. The title of acolyte is still only given to men as it is historically a minor order of ordained ministry. This term is now usually reserved for the ministry that all who are to be promoted to the diaconate receives at least six months before being ordained a deacon (c.