Why Rabbi Meyer Matters 25 Years After His Passing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Participant Bios

THE TIKVAH FUND 165 E. 56th Street New York, New York 10022 Reason, Revelation and Jewish Thought July 28, 2014 – August 1, 2014 Participant Biographies Asael Abelman, Advanced Institute Participant Israel Asael Abelman is the head of the history department at Herzog College and a member of faculty in the Shalem College, both in Israel. In the last few years he has also been a teacher at Ein Prat—the Academy for Leadership. Dr. Abelman holds a Ph.D. in modern Jewish history and has published in numerous academic and popular Israeli journals and newspapers. Matthew Ackerman, Advanced Institute Participant United States Matthew Ackerman has worked for a variety of Jewish organizations, including the Anti-Defamation League and the Jewish Community Relations Council. Most recently he served as recruitment director for Taglit-Birthright Israel. Before his work in Jewish communal service he was a Peace Corps volunteer in Ecuador, and he worked as a public high school teacher in Brooklyn as a New York City Teaching Fellow. His writing has appeared in Commentary, Tablet, and other publications. He is a graduate of Johns Hopkins University and the Jewish Theological Seminary. Nerya Cohen, Advanced Institute Participant Israel Nerya Cohen is a teacher at Tichon Hadash High School in Tel Aviv, where he coordinates the Judaic studies program and is a member of the board. He is an alumnus of the Revivim honors program at the Hebrew University, where he concentrated in Biblical and Judaic studies. After finishing his B.A., he completed his LL.B. at the Bar-Ilan Law School, where he served as the editor of the Bar-Ilan Law Journal for three years. -

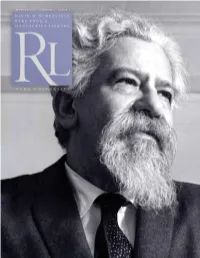

D U K E U N I V E R S I

WINTER 2013 VOLUME 1 ISSUE 2 DUKE UNIVERSITY WINTER 2013 VOLUME 1 ISSUE 2 In this Issue 4 Passionate Wisdom Abraham Joshua Heschel 8 India Through a British Lens The Photographs of Samuel Bourne 10 Out of the Shadows Economist Anna Schwartz David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library 12 A Historian Who Made History John Hope Franklin Rita DiGiallonardo Holloway University Librarian & Vice Provost for Library Affairs Deborah Jakubs 13 Digitizing the Long Civil Rights Director of the Rubenstein Library Movement Naomi L. Nelson 14 Madison Avenue Icons Director of Communications Aaron Welborn Help Celebrate Milestones RL Magazine is published twice yearly by the David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Duke 16 New and Noteworthy University Libraries, Durham, NC, 27708. It is distributed to friends and colleagues of the Rubenstein Library. Letters 18 MacArthur “Genius” Visits Duke to the editor, inquiries, and changes of address should be In Filmmaker Series sent to the Rubenstein Library Publications, Box 90185, Duke University, Durham, NC 27708. 19 Exhibits and Events Calendar Copyright 2013 Duke University Libraries. Photography by Mark Zupan except where otherwise noted. Designed by Pam Chastain Design, Durham, NC. Printed by Riverside Printing. Printed on recycled paper. On the Cover: Portrait of Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel Find us online: by Lotte Jacobi. ©The Lotte Jacobi Collection, University of library.duke.edu/rubenstein New Hampshire. Left: Detail from Livio Sanuto’s Geografia Dell’africa, 1588 Check out our blog: blogs.library.duke.edu/rubenstein Like us on Facebook: facebook.com/rubensteinlibrary WelcomeRenovation time is finally here. In the last issue of RL Magazine, I shared our plans to completely renovate the David M. -

In Argentina: Antisemitism, Exclusion, and the Formation of Argentine Nationalism and Identity in the 20Th Century and During Military Rule (1976-1983)

Bowdoin College Bowdoin Digital Commons Honors Projects Student Scholarship and Creative Work 2021 The Jewish “Other” in Argentina: Antisemitism, Exclusion, and the Formation of Argentine Nationalism and Identity in the 20th Century and during Military Rule (1976-1983) Marcus Helble Bowdoin College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.bowdoin.edu/honorsprojects Part of the Jewish Studies Commons, and the Latin American History Commons Recommended Citation Helble, Marcus, "The Jewish “Other” in Argentina: Antisemitism, Exclusion, and the Formation of Argentine Nationalism and Identity in the 20th Century and during Military Rule (1976-1983)" (2021). Honors Projects. 235. https://digitalcommons.bowdoin.edu/honorsprojects/235 This Open Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship and Creative Work at Bowdoin Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Projects by an authorized administrator of Bowdoin Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Jewish “Other” in Argentina: Antisemitism, Exclusion, and the Formation of Argentine Nationalism and Identity in the 20th Century and during Military Rule (1976-1983) An Honors Paper for the Department of History By Marcus Helble Bowdoin College, 2021 ©2021 Marcus Helble Dedication To my parents, Rebecca and Joseph. Thank you for always supporting me in all my academic pursuits. And to my grandfather. Your life experiences sparked my interest in Jewish history and immigration. Thank you -

124900176.Pdf

Spiritual Radical EDWARD K. KAPLAN Yale University Press / New Haven & London [To view this image, refer to the print version of this title.] Spiritual Radical Abraham Joshua Heschel in America, 1940–1972 Published with assistance from the Mary Cady Tew Memorial Fund. Copyright © 2007 by Yale University. All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers. Set in Bodoni type by Binghamton Valley Composition. Printed in the United States of America by Sheridan Books, Ann Arbor, Michigan. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Kaplan, Edward K., 1942– Spiritual radical : Abraham Joshua Heschel in America, 1940–1972 / Edward K. Kaplan.—1st ed. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-300-11540-6 (alk. paper) 1. Heschel, Abraham Joshua, 1907–1972. 2. Rabbis—United States—Biography. 3. Jewish scholars—United States—Biography. I. Title. BM755.H34K375 2007 296.3'092—dc22 [B] 2007002775 A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. The paper in this book meets the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Committee on Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the Council on Library Resources. 10987654321 To my wife, Janna Contents Introduction ix Part One • Cincinnati: The War Years 1 1 First Year in America (1940–1941) 4 2 Hebrew Union College -

The Other/Argentina

The Other/Argentina Item Type Book Authors Kaminsky, Amy K. DOI 10.1353/book.83162 Publisher SUNY Press Rights Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Download date 29/09/2021 01:11:31 Item License http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Link to Item http://www.sunypress.edu/p-7058-the-otherargentina.aspx THE OTHER/ARGENTINA SUNY series in Latin American and Iberian Thought and Culture —————— Rosemary G. Feal, editor Jorge J. E. Gracia, founding editor THE OTHER/ARGENTINA Jews, Gender, and Sexuality in the Making of a Modern Nation AMY K. KAMINSKY Cover image: Archeology of a Journey, 2018. © Mirta Kupferminc. Used with permission. Published by State University of New York Press, Albany © 2021 State University of New York All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission. No part of this book may be stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means including electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without the prior permission in writing of the publisher. For information, contact State University of New York Press, Albany, NY www.sunypress.edu Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Kaminsky, Amy K., author. Title: The other/Argentina : Jews, gender, and sexuality in the making of a modern nation / Amy K. Kaminsky. Other titles: Jews, gender, and sexuality in the making of a modern nation Description: Albany : State University of New York Press, [2021] | Series: SUNY series in Latin American and Iberian thought and culture | Includes bibliographical references and index. -

Texto Completo (Pdf)

“Un día en el infierno”: acerca de las respuestas producidas en torno al antisemitismo público y clandestino durante la última dictadura militar Emmanuel Nicolás Kahan IdIHCS-CONICET / NEJ-IDES / IDH-UNGS Recibido: 10-08-12 Aprobado: 07-09-12 Resumen Las críticas recibidas por el régimen dictatorial argentino, alusivas a su carácter “antisemita”, datan de fecha temprana. Como se verá en el desarrollo de este trabajo, la cuestión del “antisemitismo” materializó una serie de reparos frente a la intervención militar en el plano internacional. Una serie de “Informes” de organizaciones internacionales ligadas a las denuncias de las violaciones de los derechos humanos resultan ilustrativas de la relevancia que el “trato a los judíos” cobraría en la acusación sobre las arbitrariedades perpetradas por la dictadura militar. Estos Informes se complementaron con el testimonio de Jacobo Timerman sobre los días de su cautiverio, consolidando un marco interpretativo asentado sobre un severo juicio moral que condenó particularmente a quienes consideraban como mandatarios de la DAIA. No obstante, la investigación de diversos acervos y publicaciones de los actores permite poner en suspenso ciertos a priori de la acusación. El análisis de los documentos encontrados permite identificar, a grandes rasgos, dos formas distintivas de manifestación del antisemitismo: una de carácter público y otra que funcionaba de modo clandestino. El presente trabajo abordará las diversas estrategias y las tensiones suscitadas al interior de la “comunidad judía” en torno a las formas en que se enfrentó y/o denunció estos modos de antisemitismo. Palabras-clave: Argentina, Judíos, Dictadura, Antisemitismo Abstract The criticism received by the Argentinean dictatorial regime in relation to its “anti-Semitism” appeared early on after the coup. -

World Council of Synagogues

World Council of Synagogues Proceedings of Ninth International Convention JERUSALEM, ISRAEL November 20-23, 1972 w 14-17 Kislev, 5733 3NLAMERfCAN JEWISH COMMITTED Library ri Officers 1970-1972 President MORRIS SPEIZMAN, U.S.A. Vice Presidents CHAIM CHIELL, Israel RABBI BENT MELCHIOR, Denmark JUDAH DAVID, India SAMUEL ROTHSTEIN, U.S.A. OSCAR B. DAVIS, England ADOLFO WEIL, Argentina Secretary DR. JACOB B. SHAMMASH, U.S.A. Treasurer DAVID ZUCKER, U.S.A. Honorary President EMANUEL G. SCOBLIONKO, U.S.A. Honorary Vice-President PHILIP GREENE, U.S.A. Directors-at-large W. ZEVBAIREY, Mexico DR. LOUIS LEVITSKY, U.S.A. GERRARD BERMAN, U.S.A. GEORGE MAISLEN, U.S.A. DR. LEON BERNSTEIN, Argentina EMMANUEL E. MOSES, India DR. DAVID BRAILOVSKY, Chile RABBI MORTON H. NARROWE, Sweden DAVID FREEMAN, Israel BARRY PAGE, Australia DR. MIRIAM FREUND, U.S.A. JUAN PLAUT, Venezuela JACK GLADSTONE, U.S.A. HENRY N. RAPAPORT, U.S.A. BERT GODFREY, Canada *CHARLES ROSENGARTEN, U.S.A. RABBI ISRAEL M. GOLDMAN, U.S.A. ALFREDO ROSENZWEIG, Peru MRS. SYD R. GOLDSTEIN, U.S.A. LEON SCHIDLOW, Mexico *YAACOV HAHAM, Israel ENRIQUE SCHOEN, Argentina MRS. EVELYN HENKIND, U.S.A. JACOBO A. SEQUEIRA, Brazil *DR. ALFRED HIRSCHBERG, Brazil ARTHUR J. SIGGNER, Canada FRITZ HOLLANDER, Sweden PROF. ERNST SIMON, Israel VICTOR HORWITZ, U.S.A. RABBI RALPH SIMON, U.S.A. MARTIN KAMEROW, U.S.A. JACOB STEIN, U.S.A. SEYMOUR L. KATZ, U.S.A. DR. GIANFRANCO TEDESCHI, Italy VICTOR LEFF, U.S.A. ARTHUR E. TIEMANN, U.S.A. RABBI S. GERSHON LEVI, U.S.A. -

22992/RA Indexes

INDEX of the PROCEEDINGS of THE RABBINICAL ASSEMBLY ❦ INDEX of the PROCEEDINGS of THE RABBINICAL ASSEMBLY ❦ Volumes 1–62 1927–2000 Annette Muffs Botnick Copyright © 2006 by The Rabbinical Assembly ISBN 0-916219-35-6 All rights reserved. No part of the text may be reproduced in any form, nor may any page be photographed and reproduced, without written permission of the publisher. Manufactured in the United States of America Designed by G&H SOHO, Inc. CONTENTS Preface . vii Subject Index . 1 Author Index . 193 Book Reviews . 303 v PREFACE The goal of this cumulative index is two-fold. It is to serve as an historical reference to the conventions of the Rabbinical Assembly and to the statements, thoughts, and dreams of the leaders of the Conser- vative movement. It is also to provide newer members of the Rabbinical Assembly, and all readers, with insights into questions, problems, and situations today that are often reminiscent of or have a basis in the past. The entries are arranged chronologically within each author’s listing. The authors are arranged alphabetically. I’ve tried to incorporate as many individuals who spoke on a subject as possible, as well as included prefaces, content notes, and appendices. Indices generally do not contain page references to these entries, and I readily admit that it isn’t the professional form. However, because these indices are cumulative, I felt that they were, in a sense, an historical set of records of the growth of the Conservative movement through the twentieth century, and that pro- fessional indexers will forgive these lapses. -

No Todo Lo Que Brilla Es Oro. El Periódico Nueva Presencia Y La Dictadura Militar En Argentina, 1977-1983

XII Jornadas Interescuelas/Departamentos de Historia. Departamento de Historia, Facultad de Humanidades y Centro Regional Universitario Bariloche. Universidad Nacional del Comahue, San Carlos de Bariloche, 2009. No todo lo que brilla es oro. El periódico Nueva Presencia y la dictadura militar en Argentina, 1977-1983. Kahan, Emmanuel N. Cita: Kahan, Emmanuel N. (2009). No todo lo que brilla es oro. El periódico Nueva Presencia y la dictadura militar en Argentina, 1977-1983. XII Jornadas Interescuelas/Departamentos de Historia. Departamento de Historia, Facultad de Humanidades y Centro Regional Universitario Bariloche. Universidad Nacional del Comahue, San Carlos de Bariloche. Dirección estable: http://www.aacademica.org/000-008/1162 Acta Académica es un proyecto académico sin fines de lucro enmarcado en la iniciativa de acceso abierto. Acta Académica fue creado para facilitar a investigadores de todo el mundo el compartir su producción académica. Para crear un perfil gratuitamente o acceder a otros trabajos visite: http://www.aacademica.org. No todo lo que brilla es oro. El semanario Nueva Presencia y la dictadura militar en Argentina, 1977-1983. • Emmanuel Nicolás Kahan Introducción. El 15 de noviembre de 2007, la Legislatura de la Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires resuelve, tras un proyecto presentado por el Diputado Miguel Talento, brindar un homenaje al semanario Nueva Presencia “por su compromiso con los derechos humanos y su lucha contra la última dictadura militar”.1 El homenaje se concretaría con la colocación de una placa recordatoria en el frente de la calle Castelli N° 330 de la Capital Federal, lugar donde funcionó la redacción del semanario. Poco más de un año después, el 9 de diciembre del 2008, tuvo lugar el acto y colocación de la placa recordatoria.2 En su alocución Schiller tendía un puente identificatorio entre las políticas represivas del pasado- la desaparición forzada de personas- y las del presente- criminalización de la pobreza y “gatillo fácil”. -

Memory and Truth in Human Rights: the Argentina Case

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School February 2013 Memory and Truth in Human Rights: The Argentina Case. The sI sue of Truth and Memory in the Aftermath of Gross Human Rights Violations in Argentina. Andres Delgado University of South Florida, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the Latin American Studies Commons, and the Political Science Commons Scholar Commons Citation Delgado, Andres, "Memory and Truth in Human Rights: The Argentina Case. The sI sue of Truth and Memory in the Aftermath of Gross Human Rights Violations in Argentina." (2013). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/4306 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Memory and Truth in Human Rights: The Argentina Case. The Issue of Truth and Memory in the Aftermath of Gross Human Rights Violations in Argentina. by Andrés Delgado C. A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Arts Institute for the Study of Latin American and the Caribbean College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: Rachel May, Ph.D. Bernd Reiter, Ph.D. Peter Funke, Ph.D. Date of Approval: October 29, 2012 Keywords: Transitional Justice, State Terror, CONADEP, Desaparecidos, Relatives Organizations Copyright © 2012, Andrés Delgado C. Dedication Le dedico esta tesis a mis padres, Jesus M. -

I Have No Right to Be Silent, the Human Rights Legacy of Rabbi Marshall T

I Have No Right to Be Silent, The Human Rights Legacy of Rabbi Marshall T. Meyer Learning Activities for Students of Spanish and Latin American Studies Dominique Gálvez The Early College Experience Program, The Dodd Center, El Instituto and the Department of Literatures, Cultures and Languages at the University of Connecticut 1 I Have No Right to Be Silent, The Human Rights Legacy of Rabbi Marshall T. Meyer Curriculum Overview The learning activities developed for this unit of study are based on various themes presented in Duke University’s traveling exhibit I Have No Right to Be Silent, The Human Rights Legacy of Rabbi Marshall T. Meyer and incorporates the use of original documents that are available online in the Marshall T. Meyer Papers from the Duke University Libraries Digital Collection. The learning activities in this unit help students consider the roles and responsibilities that individuals have when faced with human rights violations in their communities. It also provides a context for considering the impact that one individual can have by choosing to not remain silent or indifferent when others are being oppressed. In this unit, students will review Marshall Meyer’s sermons, anecdotes and short stories about Marshall Meyer, correspondence with political prisoners, human rights documents, photographs, newspaper headlines, political cartoons, testimonies, literature and excerpts from the CONADEP report to learn about the last military dictatorship in Argentina and fully appreciate the actions that Marshall Meyer took to defend human rights. The concepts of memory, democracy, human rights, social activism, and Jewish identity are woven into this curriculum. These activities have been designed for students who have an intermediate to advanced level of Spanish proficiency, although they could be modified for other levels of language proficiency. -

CAPITULO UNO La Prensa Argentina

Universidad de Palermo Facultad de Humanidades y Ciencias Sociales Tesis de grado Nueva Presencia y los desaparecidos Alumno: Hernán Dobry Legajo: 26057/4 Fecha: 31 de agosto de 2004 44 INDICE Introducción 3 Capítulo Uno: La prensa argentina 5 Capítulo Dos: La Comunidad Judía Argentina 17 Capítulo Tres: Nueva Presencia 33 Capítulo Cuatro: Del nacimiento al Mundial (1977-1978) 40 Capítulo Cinco: Del Mundial a Malvinas (1978-1982) 44 Capítulo Seis: De Malvinas a la democracia (1982-1983) 62 Epílogo 81 Lista de personas entrevistadas 83 Bibliografía 84 Anexos 87 45 INTRODUCCION Los desaparecidos fueron un tema tabú, y hasta podría decirse prohibido, durante la última dictadura militar que gobernó la Argentina entre 1976 y 1983. Los medios masivos de comunicación callaron ante el drama que vivían miles de familias. La sociedad actuó de igual manera. El rabino Marshall Theodor Meyer, uno de los más fervientes luchadores por los dere- chos humanos, define, con claridad, el clima que reinaba en el país en esos días: “Hemos vivido años de salvajismo y barbarie porque todo el mundo vivía con el undécimo manda- miento que es el que dice: ‘argentino no te metás y quedate piola en el molde’”1. Algunos medios fueron la excepción que confirma la regla, a pesar de la censura y el temor que circulaba entre las redacciones. El Buenos Aires Herald, principalmente, y La Prensa, con algunos editoriales de Manfred Schöenfeld, son los únicos reconocidos por ani- marse a quebrar el silencio. La amnesia, el olvido o la ignorancia dejaron fuera de la historia a uno de los más fer- vientes defensores de los derechos humanos durante el gobierno militar: Nueva Presencia.