World Council of Synagogues

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FF12MC: a Revised AMBER Forcefield and New Protein Simulation Protocol

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/061184; this version posted July 11, 2016. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY 4.0 International license. FF12MC: A revised AMBER forcefield and new protein simulation protocol Yuan-Ping Pang Computer-Aided Molecular Design Laboratory, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN 55905, USA Corresponding author: Stabile 12-26, Mayo Clinic, 200 First Street SW, Rochester, MN 55905, USA; E-mail address: [email protected] Short title: FF12MC: A new protein simulation protocol Keywords: Protein folding; Protein dynamics; Protein simulation; Protein structure refinement; Molecular dynamics simulation; Force field; Chignolin; CLN025; Trp-cage; BPTI. bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/061184; this version posted July 11, 2016. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY 4.0 International license. ABSTRACT Specialized to simulate proteins in molecular dynamics (MD) simulations with explicit solvation, FF12MC is a combination of a new protein simulation protocol employing uniformly reduced atomic masses by tenfold and a revised AMBER forcefield FF99 with (i) shortened C– H bonds, (ii) removal of torsions involving a nonperipheral sp3 atom, and (iii) reduced 1–4 interaction scaling -

Refinement of Protein Conformations Using a Macromolecular Energy Minimization Procedure

J. Mol. Biol. (1969) 46, 269-279 Refinement of Protein Conformations using a Macromolecular Energy Minimization Procedure MICHAEL LEVITT AND SHNEIOR LIFSON Weixmann Institute of Science Rehovot, Israel (Received 3 December 1968, and in revised form 29 July, 1969) This paper presents a rapid refinement procedure capable of deriving the stable conformation of a macromolecule from experimental model co-ordinates. All the degrees of freedom of the molecule are allowed to vary and all parts of the structure are refined simultaneously in a general force-field. The procedure has been applied to myoglobin and lysozyme. The deviations of peptide bonds from planar conformation and of various bond angles from their respective average values are found to contribute significantly to the retied protein conformation. Hydrogen atoms are not included in the present refinement. A set of non-bonded potential functions, applicable to the equilibrium of a folded protein in an aqueous medium, is described and tested on myoglobin. 1. Introduction The Cartesian co-ordinates of a protein molecule have been obtained from measure- ments on a rigid wire model, built according to electron density maps derived from X-ray diffraction measurements. The errors inherent in measuring a mechanical model give rise to highly strained bond lengths and angles. Much of this strain can be relieved without affecting the relative orientation of parts of the molecule. Diamond (1966) proposed a co-ordinate refinement procedure which varied certain dihedral and bond angles to give the best fit to the rough measured co-ordinates. The fixed bond lengths and angles of each amino acid residue were obtained from crystallographic studies of small molecules. -

IYUNIM Multidisciplinary Studies in Israeli and Modern Jewish Society

IYUNIM Multidisciplinary Studies in Israeli and Modern Jewish Society IYUNIM Multidisciplinary Studies in Israeli and Modern Jewish Society Volume 31 2019 Editors: Avi Bareli, Ofer Shiff Assistant Editor: Orna Miller Editorial Board: Avi Bareli, Avner Ben-Amos, Kimmy Caplan, Danny Gutwein, Menachem Hofnung, Paula Kabalo, Nissim Leon, Kobi Peled, Shalom Ratzabi, Ilana Rosen, Ofer Shiff Founding Editor: Pinhas Ginossar Style Editing: Ravit Delouya, Herzlia Efrati, Keren Glicklich, Yeal Ofir, Meira Turetzky Proofreading: Margalit Abas-Gian, Leah Lutershtein Abstracts Editing: Moshe Tlamim Cover Design: Shai Zauderer Production Manager: Hadas Blum ISSN 0792-7169 Danacode 1246-10023 © 2019 All Rights Reserved The Ben-Gurion Research Institute Photo Typesetting: Sefi Graphics Design, Beer Sheva Printed in Israel at Art Plus, Jerusalem CONTENTS Society Uri Cohen Shneior Lifson and the Founding of the Open University, 1970-1976 7 Oded Heilbronner Moral Panic and the Consumption of Pornographic Literature in Israel in the 1960s 60 Danny Gutwein The Chizbatron and the Transformation of the Palmach’s Pioneering Ethos, 1948-1950 104 Defense Yogev Elbaz A Calculated Risk: Israel’s Intervention in Jordan’s Civil War, September 1970 152 Nadav Fraenkel The Etzion Bloc Settlements and the Yishuv’s Institutions in the War of Independence 182 Mandate Era Ada Gebel Yitzhak Breuer and the Question of Sovereignty in the Land of Israel 215 Dotan Goren The Hughes Land Affair in Transjordan 244 Culture and Literature Liora Bing-Heidecker Choreo-trauma: The Poetics of Loss in the Dance Works of Judith Arnon and of Rami Beer 272 Or Aleksandrowicz The Façade of Building: Exposed Building Envelope Technologies in Modern Israeli Architecture 306 Michael Gluzman David Grossman’s Writing of Bereavement 349 Abbreviations 381 List of Participants 382 English Abstracts i ABSTRACTS ABSTRACTS Shneior Lifson and the Founding of the Open University, 1970-1976 Uri Cohen The idea of an Open University in Israel gained traction in 1970 and in 1976 it opened its doors for classes. -

Participant Bios

THE TIKVAH FUND 165 E. 56th Street New York, New York 10022 Reason, Revelation and Jewish Thought July 28, 2014 – August 1, 2014 Participant Biographies Asael Abelman, Advanced Institute Participant Israel Asael Abelman is the head of the history department at Herzog College and a member of faculty in the Shalem College, both in Israel. In the last few years he has also been a teacher at Ein Prat—the Academy for Leadership. Dr. Abelman holds a Ph.D. in modern Jewish history and has published in numerous academic and popular Israeli journals and newspapers. Matthew Ackerman, Advanced Institute Participant United States Matthew Ackerman has worked for a variety of Jewish organizations, including the Anti-Defamation League and the Jewish Community Relations Council. Most recently he served as recruitment director for Taglit-Birthright Israel. Before his work in Jewish communal service he was a Peace Corps volunteer in Ecuador, and he worked as a public high school teacher in Brooklyn as a New York City Teaching Fellow. His writing has appeared in Commentary, Tablet, and other publications. He is a graduate of Johns Hopkins University and the Jewish Theological Seminary. Nerya Cohen, Advanced Institute Participant Israel Nerya Cohen is a teacher at Tichon Hadash High School in Tel Aviv, where he coordinates the Judaic studies program and is a member of the board. He is an alumnus of the Revivim honors program at the Hebrew University, where he concentrated in Biblical and Judaic studies. After finishing his B.A., he completed his LL.B. at the Bar-Ilan Law School, where he served as the editor of the Bar-Ilan Law Journal for three years. -

Kosmas 2018 Ns

New Series Vol. 1 N° 2 by the Czechoslovak Society of Arts and Sciences KOSMAS CZECHOSLOVAK AND CENTRAL EUROPEAN JOURNAL KOSMAS ISSN 1056-005X ©2018 by the Czechoslovak Society of Arts and Sciences (SVU) Kosmas: Czechoslovak and Central European Journal (Formerly Kosmas: Journal of Czechoslovak and Central European Studies, Vols. 1-7, 1982-1988, and Czechoslovak and Central European Journal, Vols. 8-11, (1989-1993). Kosmas is a peer reviewed, multidisciplinary journal that focuses on Czech, Slovak and Central European Studies. It publishes scholarly articles, memoirs, research materials, and belles-lettres (including translations and original works), dealing with the region and its inhabitants, including their communities abroad. It is published twice a year by the Czechoslovak Society of Arts and Sciences (SVU). Editor: Hugh L. Agnew (The George Washington University) Associate Editors: Mary Hrabík Šámal (Oakland University) Thomas A. Fudge (University of New England, Australia) The editors assume no responsibility for statements of fact or opinion made by contributors. Manuscript submissions and correspondence concerning editorial matters should be sent via email to the editor, Hugh L. Agnew. The email address is [email protected]. Please ensure that you reference “Kosmas” in the subject line of your email. If postal correspondence proves necessary, the postal address of the editor is Hugh L. Agnew, History Department, The George Washington University, 801 22nd St. NW, Washington, DC, 20052 USA. Books for review, book reviews, and all correspondence relating to book reviews should be sent to the associate editor responsible for book reviews, Mary Hrabík Šámal, at the email address [email protected]. If postal correspondence proves necessary, send communications to her at 2130 Babcock, Troy, MI, 48084 USA. -

A. Personal Statement B. Positions, Honors and Review Service

Program Director/Principal Investigator (Last, First, Middle) : LEVITT, Michael BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH Provide the following information for the Senior/key personnel and other significant contributors in the order listed on Form Page 2. Follow this format for each person. DO NOT EXCEED FOUR PAGES. NAME POSITION TITLE Michael LEVITT eRA COMMONS USER NAME (credential, e.g., agency login) Professor LEVITT.MICHAEL EDUCATION/TRAINING (Begin with baccalaureate or other initial professional education, such as nursing, and include postdoctoral training.) INSTITUTION AND LOCATION DEGREE FIELD OF STUDY (if applicable) MM/YY King's College, London, England B.Sc. 06/1967 Physics Royal Society Fellow, Weizmann Institute Israel N/A 09/1968 Conformation Analysis Cambridge University, England Ph.D. 12/1971 Computational Biology A. Personal Statement I pioneered of computational biology setting up the conceptual and theoretical framework for a field that I am still actively involved in at all levels. More specifically, I still write and maintain computer programs of all types including large simulation packages and molecular graphics interfaces. I have also developed a high-level of expertise in Perl scripting, as well as in the advanced use of the Office Suite of programs (Word, Excel and PowerPoint), which is more important and rare than it may seem. My research focuses on three different but inter-related areas of research. First, we are interested in predicting the folding of a polypeptide chain into a protein with a unique native-structure with particular emphasis on how the hydrophobic forces affect the pathway. We expect hydrophobic interactions to energetically favor structure that are more native-like. -

D U K E U N I V E R S I

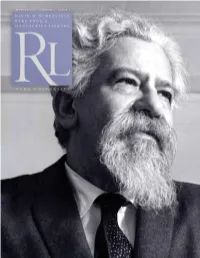

WINTER 2013 VOLUME 1 ISSUE 2 DUKE UNIVERSITY WINTER 2013 VOLUME 1 ISSUE 2 In this Issue 4 Passionate Wisdom Abraham Joshua Heschel 8 India Through a British Lens The Photographs of Samuel Bourne 10 Out of the Shadows Economist Anna Schwartz David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library 12 A Historian Who Made History John Hope Franklin Rita DiGiallonardo Holloway University Librarian & Vice Provost for Library Affairs Deborah Jakubs 13 Digitizing the Long Civil Rights Director of the Rubenstein Library Movement Naomi L. Nelson 14 Madison Avenue Icons Director of Communications Aaron Welborn Help Celebrate Milestones RL Magazine is published twice yearly by the David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Duke 16 New and Noteworthy University Libraries, Durham, NC, 27708. It is distributed to friends and colleagues of the Rubenstein Library. Letters 18 MacArthur “Genius” Visits Duke to the editor, inquiries, and changes of address should be In Filmmaker Series sent to the Rubenstein Library Publications, Box 90185, Duke University, Durham, NC 27708. 19 Exhibits and Events Calendar Copyright 2013 Duke University Libraries. Photography by Mark Zupan except where otherwise noted. Designed by Pam Chastain Design, Durham, NC. Printed by Riverside Printing. Printed on recycled paper. On the Cover: Portrait of Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel Find us online: by Lotte Jacobi. ©The Lotte Jacobi Collection, University of library.duke.edu/rubenstein New Hampshire. Left: Detail from Livio Sanuto’s Geografia Dell’africa, 1588 Check out our blog: blogs.library.duke.edu/rubenstein Like us on Facebook: facebook.com/rubensteinlibrary WelcomeRenovation time is finally here. In the last issue of RL Magazine, I shared our plans to completely renovate the David M. -

In Argentina: Antisemitism, Exclusion, and the Formation of Argentine Nationalism and Identity in the 20Th Century and During Military Rule (1976-1983)

Bowdoin College Bowdoin Digital Commons Honors Projects Student Scholarship and Creative Work 2021 The Jewish “Other” in Argentina: Antisemitism, Exclusion, and the Formation of Argentine Nationalism and Identity in the 20th Century and during Military Rule (1976-1983) Marcus Helble Bowdoin College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.bowdoin.edu/honorsprojects Part of the Jewish Studies Commons, and the Latin American History Commons Recommended Citation Helble, Marcus, "The Jewish “Other” in Argentina: Antisemitism, Exclusion, and the Formation of Argentine Nationalism and Identity in the 20th Century and during Military Rule (1976-1983)" (2021). Honors Projects. 235. https://digitalcommons.bowdoin.edu/honorsprojects/235 This Open Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship and Creative Work at Bowdoin Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Projects by an authorized administrator of Bowdoin Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Jewish “Other” in Argentina: Antisemitism, Exclusion, and the Formation of Argentine Nationalism and Identity in the 20th Century and during Military Rule (1976-1983) An Honors Paper for the Department of History By Marcus Helble Bowdoin College, 2021 ©2021 Marcus Helble Dedication To my parents, Rebecca and Joseph. Thank you for always supporting me in all my academic pursuits. And to my grandfather. Your life experiences sparked my interest in Jewish history and immigration. Thank you -

124900176.Pdf

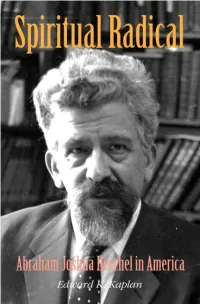

Spiritual Radical EDWARD K. KAPLAN Yale University Press / New Haven & London [To view this image, refer to the print version of this title.] Spiritual Radical Abraham Joshua Heschel in America, 1940–1972 Published with assistance from the Mary Cady Tew Memorial Fund. Copyright © 2007 by Yale University. All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers. Set in Bodoni type by Binghamton Valley Composition. Printed in the United States of America by Sheridan Books, Ann Arbor, Michigan. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Kaplan, Edward K., 1942– Spiritual radical : Abraham Joshua Heschel in America, 1940–1972 / Edward K. Kaplan.—1st ed. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-300-11540-6 (alk. paper) 1. Heschel, Abraham Joshua, 1907–1972. 2. Rabbis—United States—Biography. 3. Jewish scholars—United States—Biography. I. Title. BM755.H34K375 2007 296.3'092—dc22 [B] 2007002775 A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. The paper in this book meets the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Committee on Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the Council on Library Resources. 10987654321 To my wife, Janna Contents Introduction ix Part One • Cincinnati: The War Years 1 1 First Year in America (1940–1941) 4 2 Hebrew Union College -

The Other/Argentina

The Other/Argentina Item Type Book Authors Kaminsky, Amy K. DOI 10.1353/book.83162 Publisher SUNY Press Rights Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Download date 29/09/2021 01:11:31 Item License http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Link to Item http://www.sunypress.edu/p-7058-the-otherargentina.aspx THE OTHER/ARGENTINA SUNY series in Latin American and Iberian Thought and Culture —————— Rosemary G. Feal, editor Jorge J. E. Gracia, founding editor THE OTHER/ARGENTINA Jews, Gender, and Sexuality in the Making of a Modern Nation AMY K. KAMINSKY Cover image: Archeology of a Journey, 2018. © Mirta Kupferminc. Used with permission. Published by State University of New York Press, Albany © 2021 State University of New York All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission. No part of this book may be stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means including electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without the prior permission in writing of the publisher. For information, contact State University of New York Press, Albany, NY www.sunypress.edu Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Kaminsky, Amy K., author. Title: The other/Argentina : Jews, gender, and sexuality in the making of a modern nation / Amy K. Kaminsky. Other titles: Jews, gender, and sexuality in the making of a modern nation Description: Albany : State University of New York Press, [2021] | Series: SUNY series in Latin American and Iberian thought and culture | Includes bibliographical references and index. -

Yaakov Levy, B

Prof. Yaakov (Koby) Levy February 2019 The Morton and Gladys Pickman professional chair in Structural Biology Department of Structural Biology Weizmann Institute of Science Rehovot 76100, Israel Tel: +972 (8) 934-4587 Fax: +972 (8) 934-4136 E-mail: [email protected] CURRICULUM VITAE Personal details Date & Place of Birth March 22, 1972; Tel-Aviv, Israel Citizenship Israeli Marital Status Married, three children Homepage http://www.weizmann.ac.il/Structural_Biology/Levy/ Languages Hebrew (mother language), English, Spanish 6/1994 – 6/1997 Military service in the Israel Defense Forces Education 6/1997 – 6/2002 Tel-Aviv University, Tel-Aviv, Israel. Ph.D., Department of Chemical Physics, School of Chemistry Theoretical and computational biophysics, Thesis title: "Multidimensional Potential Energy Surfaces of Biological Macromolecules". Prof. Joshua Jortner and Dr. Oren Becker. 1991 – ‘94 Technion- Israel Institute of Technology, Haifa, Israel. B.Sc., in Chemistry (summa cum laude). Teaching Experience 2008, 2009 Protein Structure Function I, WIS 2007, 2015, 2017 Protein Structure Function II, WIS 2007, 2011, 2013, Computational Molecular Biophysics, WIS 2019 1998 – ‘02 Teaching special courses in General Chemistry (The School of Dental Medicine and the Pre- University project, Tel-Aviv University). 1 Teaching Assistant in General and Physical Chemistry courses (The School of Medicine, Tel- Aviv University), Laboratory course (General Chemistry), Statistical Thermodynamics and in analytical chemistry courses (The School of Chemistry, Tel-Aviv University). 1999 – ‘01 Member in the center for improving teaching in Tel-Aviv university. 1993 – ‘94 Teaching chemistry (for matriculation), “Shuv” High-School, Haifa. Honors and Awards 1992, 1993, President's award for high academic achievements (Technion, Israel Inst. -

Report of the Committee on Post-Secondary Education

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 059 709 JC 720 062 AUTHOR Lefs-n, Shneior TITLE Repor of the Committee on Post-Secondary Education. INSTITUTION Ministry of Education and Culture, Jerusalem (Israel). PUB DATE Dec 71 NOTE 72p. EDRS PRICE MF-$0.55 HC-$3.29 DESCRIPTORS *Educational Development; *Educational Planning; *Foreign Countries: *Institutional Role: *Junior Colleges IDENTIFIERS *Isr6.e1 ABSTRACT This report was produced by a committee appointed by the Council for Higher Education of the Ministry of Education and culture (Israel) to perform the following three major tasks: (1) review all facets of post-secondary education excluding university activities; (2) suggest principles on which to base the development of post-secondary education; and (3) make long- and short-run suggestions for planning and directing various types of post-secondary education. Other major efforts were to initiate discussion regarding communication between different educational levels; the nature and value of awarded certificates; the possibility of using television, radio, and postal services for instructional purposes; and the concept of post-secondary institutions offering a wide variety of courses. The main part of the report consists of a review of post-secondary educational institutions and their role. Such areas as admissions, distribution of students in morning and evening courses, geographical distribution of institutions, program potential, and the role of teacherm are discussed. Tables of descriptive statistics relating to Israeli education in general as well as post-secondary education are appended. (A14 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH. EDUCATION & WELFARE OFFICE OF EDUCATION THIS DOCUMENT HAS BEEN REPRO- DUCED EXACTLY AS RECEIVED FROM THE PERSON OR ORGANIZATION ORIG- INATING IT POINTS OF VIEW OR ORIN- IONS STATED DO NOT NECESSARILY REPRESEN1 OFFICIAL OFFICE OF EuL).