Women, Business and the Law 2021

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rythme Et Poésie : Une Entrevue Avec Jocelyn Bruno, Alias Dramatik

Rythme et poésie : une entrevue avec Jocelyn Bruno, alias Dramatik. Par Jean-Sébastien Ménard Dans le cadre des activités de l’initiative Le français s’affiche et grâce au programme de l’UNEQ intitulé Parlez-moi d’une langue, Jocelyn Bruno, alias Dramatik, l’un des pionniers de la scène hip-hop québécoise et cofondateur du groupe Muzion, est venu rencontrer les étudiants de l’École nationale d’aérotechnique le mercredi 15 novembre 2017 afin de leur parler, notamment, de son parcours et de son rapport à la langue française. Nous publions ici l’entrevue qu’il nous a accordée. Photo de Gunther Gamper Dramatik, est-ce que tu peux nous parler de ton parcours? Je suis né à Montréal, en 1975, à l’époque de Goldorak, les ancêtres de Transformers. Très tôt dans ma vie, j’ai eu des problèmes de bégaiements à cause de troubles affectifs émotifs. J’ai eu beaucoup de problèmes avec la violence conjugale. Mon nom, Dramatik, vient de là. Ça 1 représente tous les drames que j’ai connus et vécus. Très jeune, on m’a placé en Centre d’accueil… À 6 ans, j’étais dépressif. Je ne parlais pas beaucoup et je bégayais. Je parlais créole, français et anglais. Vers mes 7-8 ans, j’ai fait une fugue de mon Centre d’accueil et c’est à ce moment-là que j’ai décidé de prendre ma vie en main. Vers 14-15 ans, j’ai quitté l’école (j’ai décroché et raccroché souvent). J’avais tellement de problèmes avec l’adolescence, avec la rue, avec l’appartenance… C’est à cette époque que j’ai commencé à faire du rap. -

Pheasant Season Slow to the Last Veteran, Is Dead Red Cross Drive

Nebrask~ st~te Historical ooctety \. I THE . r i' '. .• '•.' .... '. ..~ . I r RED CROSS "The Paper \Vith The Pictures" "Read by 3~000 Families Every \Veeh RED CROSS Established April, 1882 THE ORO QUIZ, ORO, NEBRASKA \VEONESDAY, NOVEMBER 5. 1941 Vol. 59 No, 32 New Chevrolet Brings Grin to \Vinner's Face Four Young People Escaped Death in This \Vreck I Chanticleers Take John M. Lindsay, ~ 11942 Fair to Be LOUll City 34 to 0 Last Civil War Held on Grounds in Fast Grid Ganle Veteran, Is Dead Late in August On Defensive First Frame, Burwell Man Heeds Call at Clement, McGinnis, Dale and Ord Comes Back strong to Age of 93; Served Nineteen Misko, Reelected Officers; Continue Title March, Months in Iowa Infantry, Pearson New Director. On the detensive throughout the first quarter of their game with Burwell- (Spedal)-The last of Decision to hold the 1942 Valley Loup ·Cily at 13ussell park field Fri the Boys in Blue answered the county fair on the fair grounds in day evening, the OrO. Chanticleers final' tans and passed from the its entirely rather than to have en- came back strong and won 34 to o. earthly scene when John M. Lind- tertalmuent features "Oil the streets • .Apparently the Chanticleers were say, 93, 'who' is 'belleH;d to have and exhibits Oil the grounds was victims of over-confidenee Iroiu been the last surviving veteran of made on Monday at the annual their lopsided win over Ravenna as the Civil War. in thls part of the meeting of stockholders held in the the ganie against Loup City began state, died in the home of his niece, district court room here, It was and early in the period they found Who wouldn't grin it he suddenly learned that he had won a new Mrs. -

Arabization and Linguistic Domination: Berber and Arabic in the North of Africa Mohand Tilmatine

Arabization and linguistic domination: Berber and Arabic in the North of Africa Mohand Tilmatine To cite this version: Mohand Tilmatine. Arabization and linguistic domination: Berber and Arabic in the North of Africa. Language Empires in Comparative Perspective, DE GRUYTER, pp.1-16, 2015, Koloniale und Postkoloniale Linguistik / Colonial and Postcolonial Linguistics, 978-3-11-040836-2. hal-02182976 HAL Id: hal-02182976 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02182976 Submitted on 14 Jul 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Arabization and linguistic domination: Berber and Arabic in the North of Africa Mohand Tilmatine To cite this version: Mohand Tilmatine. Arabization and linguistic domination: Berber and Arabic in the North of Africa. Language Empires in Comparative Perspective, DE GRUYTER, pp.1-16, 2015, Koloniale und Postkoloniale Linguistik / Colonial and Postcolonial Linguistics 978-3-11-040836-2. hal-02182976 HAL Id: hal-02182976 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02182976 Submitted on 14 Jul 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. -

European Qualifiers

EUROPEAN QUALIFIERS - 2014/16 SEASON MATCH PRESS KITS Helsinki Olympic Stadium - Helsinki Saturday 11 October 2014 20.45CET (21.45 local time) Finland Group F - Matchday -11 Greece Last updated 12/07/2021 16:57CET Official Partners of UEFA EURO 2020 Previous meetings 2 Match background 4 Squad list 5 Head coach 7 Match officials 8 Competition facts 9 Match-by-match lineups 10 Team facts 12 Legend 14 1 Finland - Greece Saturday 11 October 2014 - 20.45CET (21.45 local time) Match press kit Helsinki Olympic Stadium, Helsinki Previous meetings Head to Head FIFA World Cup Stage Date Match Result Venue Goalscorers reached Forssell 14, 45, Riihilahti 21, Kolkka 05/09/2001 QR (GS) Finland - Greece 5-1 Helsinki 38, Litmanen 53; Karagounis 30 07/10/2000 QR (GS) Greece - Finland 1-0 Athens Liberopoulos 59 EURO '96 Stage Date Match Result Venue Goalscorers reached Litmanen 44, Hjelm 11/06/1995 PR (GS) Finland - Greece 2-1 Helsinki 54; Nikolaidis 6 Markos 22, Batista 69, 12/10/1994 PR (GS) Greece - Finland 4-0 Salonika Machlas 76, 89 EURO '92 Stage Date Match Result Venue Goalscorers reached Saravakos 49, 30/10/1991 PR (GS) Greece - Finland 2-0 Athens Borbokis 51 Ukkonen 50; 09/10/1991 PR (GS) Finland - Greece 1-1 Helsinki Tsalouchidis 74 1980 UEFA European Championship Stage Date Match Result Venue Goalscorers reached Nikoloudis 15, 25, Delikaris 23, 47, 11/10/1978 PR (GS) Greece - Finland 8-1 Athens Mavros 38, 44, 75 (P), Galakos 81; Heiskanen 61 Ismail 35, 82, 24/05/1978 PR (GS) Finland - Greece 3-0 Helsinki Nieminen 80 1968 UEFA European Championship -

Freedom to Fly Photo Contest Complete Details Inside

THE JOURNAL OF THE CANADIAN OWNERS AND PILOTS ASSOCIATION COPAFLIGHT MORE THAN FEBRUARY 2017 100 C LASSIFIED ADS ANNOUNCING COPA Flight’s FREEDOM To FLY PHOTO CONTEST COMPLETE DETAILS INSIDE WINTER FLY-INS NO GROWTH DO-IT-YOURSELF ADS-B COLD WEATHER DEMOGRAPHICS, ECONOMICS AFFORDABLE ACCESS TO PM#42583014 CAMARADERIE FLATTEN GA MARKET WEATHER, TRAFFIC SUPA BCAN_COPAFlight (8x10.75)_Layout 1 11/30/16 4:27 PM Page 1 WELCOME TO OUR WORLD At the heart of the most extreme missions you’ll find exceptional men prepared to entrust their security only to the most high-performing instruments. At the heart of exceptional missions you’ll find the Breitling Avenger. A concentrated blend of power, precision and functionality, Avenger models boast an ultra-sturdy construction and water resistance SUPER AVENGER II ranging from 100 to 3000 m (330 to 10,000 ft). These authentic instruments for professionals are equipped with selfwinding movements officially chronometer-certified by the COSC – the only benchmark of reliability and precision based on an international norm. Welcome to the world of extremes. Welcome to the Breitling world. BREITLING.COM SUPA BCAN_COPAFlight (8x10.75)_Layout 1 11/30/16 4:27 PM Page 1 WELCOME TO OUR WORLD COPAFLIGHT EDITOR Russ Niles CONTENTS [email protected] 250.546.6743 GRAPHIC DESIGN Shannon Swanson DISPLAY ADVERTISING SALES Katherine Kjaer 250.592.5331 [email protected] CLASSIFIED ADVERTISING SALES AND PRODUctION COORDINATOR Maureen Leigh 1.800.656.7598 [email protected] CIRCULATION Maureen Leigh ACCOUNTING -

LCSH Section K

K., Rupert (Fictitious character) Motion of K stars in line of sight Ka-đai language USE Rupert (Fictitious character : Laporte) Radial velocity of K stars USE Kadai languages K-4 PRR 1361 (Steam locomotive) — Orbits Ka’do Herdé language USE 1361 K4 (Steam locomotive) UF Galactic orbits of K stars USE Herdé language K-9 (Fictitious character) (Not Subd Geog) K stars—Galactic orbits Ka’do Pévé language UF K-Nine (Fictitious character) BT Orbits USE Pévé language K9 (Fictitious character) — Radial velocity Ka Dwo (Asian people) K 37 (Military aircraft) USE K stars—Motion in line of sight USE Kadu (Asian people) USE Junkers K 37 (Military aircraft) — Spectra Ka-Ga-Nga script (May Subd Geog) K 98 k (Rifle) K Street (Sacramento, Calif.) UF Script, Ka-Ga-Nga USE Mauser K98k rifle This heading is not valid for use as a geographic BT Inscriptions, Malayan K.A.L. Flight 007 Incident, 1983 subdivision. Ka-houk (Wash.) USE Korean Air Lines Incident, 1983 BT Streets—California USE Ozette Lake (Wash.) K.A. Lind Honorary Award K-T boundary Ka Iwi National Scenic Shoreline (Hawaii) USE Moderna museets vänners skulpturpris USE Cretaceous-Paleogene boundary UF Ka Iwi Scenic Shoreline Park (Hawaii) K.A. Linds hederspris K-T Extinction Ka Iwi Shoreline (Hawaii) USE Moderna museets vänners skulpturpris USE Cretaceous-Paleogene Extinction BT National parks and reserves—Hawaii K-ABC (Intelligence test) K-T Mass Extinction Ka Iwi Scenic Shoreline Park (Hawaii) USE Kaufman Assessment Battery for Children USE Cretaceous-Paleogene Extinction USE Ka Iwi National Scenic Shoreline (Hawaii) K-B Bridge (Palau) K-TEA (Achievement test) Ka Iwi Shoreline (Hawaii) USE Koro-Babeldaod Bridge (Palau) USE Kaufman Test of Educational Achievement USE Ka Iwi National Scenic Shoreline (Hawaii) K-BIT (Intelligence test) K-theory Ka-ju-ken-bo USE Kaufman Brief Intelligence Test [QA612.33] USE Kajukenbo K. -

Mother of the Nation: Femininity, Modernity, and Class in the Image of Empress Teimei

Mother of the Nation: Femininity, Modernity, and Class in the Image of Empress Teimei By ©2016 Alison Miller Submitted to the graduate degree program in the History of Art and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ________________________________ Chairperson Dr. Maki Kaneko ________________________________ Dr. Sherry Fowler ________________________________ Dr. David Cateforis ________________________________ Dr. John Pultz ________________________________ Dr. Akiko Takeyama Date Defended: April 15, 2016 The Dissertation Committee for Alison Miller certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Mother of the Nation: Femininity, Modernity, and Class in the Image of Empress Teimei ________________________________ Chairperson Dr. Maki Kaneko Date approved: April 15, 2016 ii Abstract This dissertation examines the political significance of the image of the Japanese Empress Teimei (1884-1951) with a focus on issues of gender and class. During the first three decades of the twentieth century, Japanese society underwent significant changes in a short amount of time. After the intense modernizations of the late nineteenth century, the start of the twentieth century witnessed an increase in overseas militarism, turbulent domestic politics, an evolving middle class, and the expansion of roles for women to play outside the home. As such, the early decades of the twentieth century in Japan were a crucial period for the formation of modern ideas about femininity and womanhood. Before, during, and after the rule of her husband Emperor Taishō (1879-1926; r. 1912-1926), Empress Teimei held a highly public role, and was frequently seen in a variety of visual media. -

New Challenges and Opportunities for Innovation Peter Piot, London

Professor Peter Piot’ Biography Baron Peter Piot KCMG MD PhD is the Director of the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, and the Handa Professor of Global Health. He was the founding Executive Director of UNAIDS and Under Secretary-General of the United Nations (1995-2008). A clinician and microbiologist by training, he co-discovered the Ebola virus in Zaire in 1976, and subsequently led pioneering research on HIV/AIDS, women’s health and infectious diseases in Africa. He has held academic positions at the Institute of Tropical Medicine, Antwerp; the University of Nairobi; the University of Washington, Seattle; Imperial College London, and the College de France, Paris, and was a Senior Fellow at the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. He is a member of the US National Academy of Medicine, the National Academy of Medicine of France, and the Royal Academy of Medicine of his native Belgium, and is a fellow of the UK Academy of Medical Sciences and the Royal College of Physicians. He is a past president of the International AIDS Society and of the King Baudouin Foundation. In 1995 he was made a baron by King Albert II of Belgium, and in 2016 was awarded an honorary knighthood KCMG. Professor Piot has received numerous awards for his research and service, including the Canada Gairdner Global Health Award (2015), the Robert Koch Gold Medal (2015), the Prince Mahidol Award for Public Health (2014), and the Hideyo Noguchi Africa Prize for Medical Research (2013), the F.Calderone Medal (2003), and was named a 2014 TIME Person of the Year (The Ebola Fighters). -

La Voix Humaine: a Technology Time Warp

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--Music Music 2016 La Voix humaine: A Technology Time Warp Whitney Myers University of Kentucky, [email protected] Digital Object Identifier: http://dx.doi.org/10.13023/ETD.2016.332 Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Myers, Whitney, "La Voix humaine: A Technology Time Warp" (2016). Theses and Dissertations--Music. 70. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/music_etds/70 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Music at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--Music by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained needed written permission statement(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine) which will be submitted to UKnowledge as Additional File. I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the irrevocable, non-exclusive, and royalty-free license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. I agree that the document mentioned above may be made available immediately for worldwide access unless an embargo applies. -

Comissão Estadual De Arbitragem De Futebol - CEAF Jogo: 77 / 2017 SÃO PAULO

Comissão Estadual de Arbitragem de Futebol - CEAF Jogo: 77 / 2017 SÃO PAULO Campeonato: Paulista - A1- Profissional / 2017 Rodada: 10 Jogo: São Bento X Santos Data: 22/03/2017 Horário: 19:30 Estádio: Estádio Municipal Walter Ribeiro / Sorocaba Arbitragem Arbitro: Marcelo Aparecido Ribeiro de Souza Arbitro Assistente 1: Alex Ang Ribeiro Arbitro Assistente 2: Eduardo Vequi Marciano Quarto Arbitro: Daniel Carfora Sottile Cronologia 1º Tempo 2º Tempo Entrada do mandante: 19:20 Atraso: Não Houve Entrada do mandante: 20:28 Atraso: Não Houve Entrada do visitante: 19:20 Atraso: Não Houve Entrada do visitante: 20:30 Atraso: 2 min Início 1º Tempo: 19:30 Atraso: Não Houve Início do 2º Tempo: 20:31 Atraso: 1 min Término do 1º Tempo: 20:15 Acréscimo: Não Houve Término do 2º Tempo: 21:18 Acréscimo: 2 min Resultado do 1º Tempo: 0 X 0 Resultado Final: 0 X 2 Relação de Jogadores São Bento Santos Nº Nome Completo do Jogador T/R P/A Registro Nº Nome Completo do Jogador T/R P/A Registro 1 Rodrigo Viana Da Conceição T P 271146/16 12 Vladimir Orlando Cardoso De Araújo Filho T P 282050/16 6 Régis Ribeiro De Souza T P 285336/16 4 Victor Ferraz Macedo T P 255227/16 3 Luiz Paulo Daniel Barbosa T P 285514/17 7 Vitor Frezarin Bueno T P 269656/16 4 Gabriel Dos Santos Nascimento T P 285748/17 8 Renato Dirnei Florencio T P 225363/15 5 Fabio Junior Nascimento Santana T P 275273/16 10 Lucas Rafael Araujo Lima T P 188158/14 2 Roberto De Jesus Machado T P 275271/16 14 David Braz De Oliveira Filho T P 251338/15 7 Renan Carvalho Mota T P 286656/17 18 Kayke Moreno De Andrade -

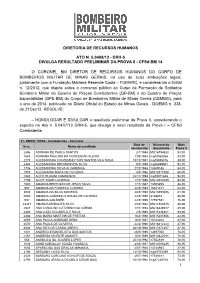

DIVULGA RESULTADO PRELIMINAR DA PROVA II - Cfsd BM 14

DIRETORIA DE RECURSOS HUMANOS ATO N. 5.0408/13 - DRH-5 DIVULGA RESULTADO PRELIMINAR DA PROVA II - CFSd BM 14 O CORONEL BM DIRETOR DE RECURSOS HUMANOS DO CORPO DE BOMBEIROS MILITAR DE MINAS GERAIS, no uso de suas atribuições legais, juntamente com a Fundação Mariana Resende Costa – FUMARC, e considerando o Edital n. 12/2012, que dispõe sobre o concurso público ao Curso de Formação de Soldados Bombeiro Militar do Quadro de Praças Combatentes (QP-BM) e do Quadro de Praças Especialistas (QPE-BM) do Corpo de Bombeiros Militar de Minas Gerais (CBMMG), para o ano de 2014, publicado no Diário Oficial do Estado de Minas Gerais - DOEMG n. 238, de 21Dez12, RESOLVE: – HOMOLOGAR E DIVULGAR o resultado preliminar da Prova II, considerando o exposto no Ato n. 5.0407/13 DRH-5, que divulga o novo resultado da Prova I – CFSd Combatente. 01- RMBH / CFSd - Combatentes - Feminino Data de Número do Nota Insc. Nome do candidato nascimento documento Prova II 2896 ADRIANA DE PAULA SANTOS 2/1/1994 MG16754930 93,00 1644 ADRIANA PAULINO DA CONCEIÇÃO ALEIXO 13/3/1984 mg12562866 83,00 2275 ALESSANDRA CONZENDEY DOS SANTOS VILA NOVA 19/12/1991 mg15955176 89,00 2434 ALESSANDRA DRUMOND DA SILVA 9/8/1989 mg16699541 92,00 1706 ALESSANDRA SILVA ALVARENGA 27/2/1984 13349148 84,00 1975 ALEXANDRA MARA DE OLIVEIRA 4/3/1986 MG12511908 65,00 2540 ALICE RUGANI CAMARGOS 24/11/1994 mg15971648 93,00 1769 ALICE TIGRE LACERDA 17/7/1985 MG12573745 92,00 1940 AMANDA BERTOLINI DE JESUS SILVA 17/1/1987 13505255 86,00 957 AMANDA DA FONSECA CORRÊA 24/5/1994 18521311 64,00 3049 AMANDA DA SILVA -

SOF Role in Combating Transnational Organized Crime to Interagency Counterterrorism Operations

“…the threat to our nations’ security demands that we… Special Operations Command North (SOCNORTH) is a determine the potential SOF roles for countering and subordinate unified command of U.S. Special Operations diminishing these violent destabilizing networks.” Command (USSOCOM) under the operational control of U.S. Northern Command (USNORTHCOM). SOCNORTH Rear Admiral Kerry Metz enhances command and control of special operations forces throughout the USNORTHCOM area of responsi- bility. SOCNORTH also improves DOD capability support Crime Organized Transnational in Combating Role SOF to interagency counterterrorism operations. Canadian Special Operations Forces Command (CAN- SOF Role SOFCOM) was stood up in February 2006 to provide the necessary focus and oversight for all Canadian Special Operations Forces. This initiative has ensured that the Government of Canada has the best possible integrated, in Combating led, and trained Special Operations Forces at its disposal. Transnational Joint Special Operations University (JSOU) is located at MacDill AFB, Florida, on the Pinewood Campus. JSOU was activated in September 2000 as USSOCOM’s joint educa- Organized Crime tional element. USSOCOM, a global combatant command, synchronizes the planning of Special Operations and provides Special Operations Forces to support persistent, networked, and distributed Global Combatant Command operations in order to protect and advance our Nation’s interests. MENDEL AND MCCABE Edited by William Mendel and Dr. Peter McCabe jsou.socom.mil Joint Special Operations University Press SOF Role in Combating Transnational Organized Crime Essays By Brigadier General (retired) Hector Pagan Professor Celina Realuyo Dr. Emily Spencer Colonel Bernd Horn Mr. Mark Hanna Dr. Christian Leuprecht Brigadier General Mike Rouleau Colonel Bill Mandrick, Ph.D.