Who's Afraid Of…?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dublin City Council City Dublin 2018 ©

© 2018 Dublin City Council City Dublin 2018 © This Map & Guide was produced by Dublin City Council in partnership with Portobello Residents Group. Special thanks to Ciarán Breathnach for research and content. Thanks also to the following for their contribution to the Portobello Walking Trail: Anthony Freeman, Joanne Freeman, Pat Liddy, Canice McKee, Fiona Hayes, Historical Picture Archive, National Library of Ireland and Dublin City Library & Archive. Photographs by Joanne Freeman and Drew Cooke. For further reading on Portobello: ‘Portobello’ by Maurice Curtis and ‘Jewish Dublin: Portraits of Life by the Liffey’ by Asher Benson. For details on Dublin City Council’s programme of walking tours and weekly walking groups, log on to www.letswalkandtalk.ie For details on Pat Liddy’s Walking Tours of Dublin, log on to www.walkingtours.ie For details on Portobello Residents Group, log on to www.facebook.com/portobellodublinireland Design & Production: Kaelleon Design (01 835 3881 / www.kaelleon.ie) Portobello derives its name from a naval battle between Great Britain and Welcome to Portobello! This walking trail emigrated, the building fell into disuse and ceased functioning as a place of worship by Spain in 1739 when the settlement of Portobello on Panama’s Carribean takes you through “Little Jerusalem”, along the mid 1970s. The museum exhibits a large collection of memorabilia and educational displays relating to the Irish Jewish communities. Close by at 1 Walworth Road is the the Grand Canal and past the homes of many The original bridge over the Grand Canal was built in 1790. In 1936 it was rebuilt and coast was captured by the British. -

Subsidies, Diplomacy, and State Formation in Europe, 1494–1789

1 The role of subsidies in seventeenth-century French foreign relations and their European context Anuschka Tischer The focus of this chapter is on the notion and practice of subsidies in French politics and diplomacy in the seventeenth century. It begins, however, with some general observations on the subject concerning the notion and practice of subsidies to demonstrate what I see as the desiderata, relevant issues, and methodological problems. I then continue with a short overview of the French practice of subsidies in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries and finally present some examples of how the notion and practice were used and described in relation to French diplomacy at the Congress of Westphalia. General observations As was pointed out in the Introduction, subsidies are one of those political notions and practices common in the early modern period that are yet to be systematically researched. The methodological problem can be compared to the notion and practice of protection, which has also only recently been put on the scholarly agenda.1 The comparison is useful as protection and subsidies have several common features and are, in fact, entangled in their use in the early modern international system. Research on protection could thus 1 Protegierte und Protektoren: Asymmetrische politische Beziehungen zwi schen Partnerschaft und Dominanz (16. bis frühes 20. Jahrhundert), ed. by Tilman Haug, Nadir Weber, and Christian Windler, Externa: Geschichte der Außenbeziehungen in neuen Perspektiven, 9 (Cologne: Böhlau Verlag, 2016); Rainer Babel, Garde et protection: Der Königsschutz in der französischen Außenpolitik vom 15. bis zum 17. Jahrhundert, Beihefte der Francia, 72 (Ostfildern: Thorbecke Verlag, 2014). -

Handle with Care

Handle with Care Jill H. Casid What was so special about this song? Well the thing was, I didn’t used to listen properly to the words; I just waited for that bit that went: “Baby, baby, never let me go...” — Kazuo Ishiguro, Never Let Me Go ([2005] 2006:70) Restating the ethically critical gap of empathy in terms of the problems of understanding the qualitative how of the way someone feels, in the language and techniques of the quantitative, Emily Dickinson begins her poem: “I measure every Grief I meet / With narrow probing eyes / I wonder if it weighs like Mine / or has an Easier size” ([1863] 1999:248–49). I begin this essay with some numbers, some quantitative measurements pertaining to the costs of the affective and material labors of care that are at the heart of our compounded condition of precarity and about which I wonder no less. Under a global capitalist system in which the terms of moneti- zation have become the sign of value, how does one measure grief, affective and material labor, or what I call throughout this essay the “labors of care”? One answer has been to measure the labors of care in terms of “cost,” rendering the physical and emotional toll on “unpaid caregiv- ers” (usually family in the enlarged sense or friends) in the quantitative fiscal language of lost Figure 1. Barbed wire fence in the film adaptation of Kazuo Ishiguro’s Never Let Me Go (2010, directed by Mark Romanek). (©2010 Twentieth Century Fox. All rights reserved) TDR: The Drama Review 56:4 (T216) Winter 2012. -

Shakespeare Macbeth

Synopsis Macbeth, set primarily in Scotland, mixes witchcraft, prophecy, and murder. Three “Weïrd Sisters” appear to Macbeth and his comrade Banquo after a battle and prophesy that Macbeth will be king and that the descendants of Banquo will also reign. When Macbeth arrives at his castle, he and Lady Macbeth plot to assassinate King Duncan, soon to be their guest, so that Macbeth can become king. After Macbeth murders Duncan, the king’s two sons flee, and Macbeth is crowned. Fearing that Banquo’s descendants will, according to the Weïrd Sisters’ predictions, take over the kingdom, Macbeth has Banquo killed. At a royal banquet that evening, Macbeth sees Banquo’s ghost appear covered in blood. Macbeth determines to consult the Weïrd Sisters again. They comfort him with ambiguous promises. Another nobleman, Macduff, rides to England to join Duncan’s older son, Malcolm. Macbeth has Macduff’s wife and children murdered. Malcolm and Macduff lead an army against Macbeth, as Lady Macbeth goes mad and commits suicide. Macbeth confronts Malcolm’s army, trusting in the Weïrd Sisters’ comforting promises. He learns that the promises are tricks, but continues to fight. Macduff kills Macbeth and Malcolm becomes Scotland’s king. Characters in the Play Three Witches, the Weïrd Sisters Scottish Nobles DUNCAN, king of Scotland LENNOX MALCOLM, his elder son ROSS DONALBAIN, Duncan’s younger son ANGUS MACBETH, thane of Glamis MENTEITH LADY MACBETH CAITHNESS SEYTON, attendant to Macbeth Three Murderers in Macbeth’s service SIWARD, commander of the English -

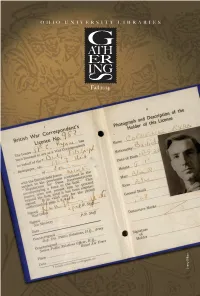

Gatherings, 2014 Fall

OHIO UNIVERSITY LIBRARIES Fall 2014 Sherry DiBari From the Dean of the Libraries MINING THE CORNELIUS RYAN ANYWHERE, ANYTIME: COLLECTION ACCESSING LIBRARIES’ MATERIALS PG 8 FINDING PARALLELS PG 5 IN THE FADING INK elebrating anniversaries is such C PG 2 an important part of our culture because MEET they underscore the value we place on TERRY MOORE heritage and tradition. Anniversaries PG 14 speak to our impulse to acknowledge the things that endure. Few places CLUES FROM AN embody those acknowledgements more AMERICAN than a library—the keeper of things LETTER that endure. As the offi cial custodian of PG 11 the University’s history and the keeper of scholarly records, no other entity on LISTENING TO OUR campus is more immersed in the history STUDENTS of Ohio University than the Libraries. PG 16 OUR DONORS A LASTING LEGACY PG 20 This year marks the 200th anniversary of Ohio University Libraries. It was on PG 18 June 15, 1814 that the Board of Trustees fi rst named their collection of books the “Library of Ohio University,” codifi ed a Credits list of seven rules for its use, and later Dean of Libraries: appointed the fi rst librarian. Scott Seaman Editor: In the 200 years since its founding, Kate Mason, coordinator of communications and assistant to the dean Ohio University Libraries is now Co-Editor: Jen Doyle, graduate communications assistant ranked as one of the top 100 research Design: libraries in North America with print University Communications and Marketing collections of over 3 million volumes Photography: and, ranked by holdings, is the 65th Sherry Dibari, graduate photography assistant largest library in North America. -

Macbeth on Three Levels Wrap Around a Deep Thrust Stage—With Only Nine Rows Dramatis Personae 14 Separating the Farthest Seat from the Stage

Weird Sister, rendering by Mieka Van Der Ploeg, 2019 Table of Contents Barbara Gaines Preface 1 Artistic Director Art That Lives 2 Carl and Marilynn Thoma Bard’s Bio 3 Endowed Chair The First Folio 3 Shakespeare’s England 5 Criss Henderson The English Renaissance Theater 6 Executive Director Courtyard-Style Theater 7 Chicago Shakespeare Theater is Chicago’s professional theater A Brief History of Touring Shakespeare 9 Timeline 12 dedicated to the works of William Shakespeare. Founded as Shakespeare Repertory in 1986, the company moved to its seven-story home on Navy Pier in 1999. In its Elizabethan-style Courtyard Theater, 500 seats Shakespeare's Macbeth on three levels wrap around a deep thrust stage—with only nine rows Dramatis Personae 14 separating the farthest seat from the stage. Chicago Shakespeare also The Story 15 features a flexible 180-seat black box studio theater, a Teacher Resource Act by Act Synopsis 15 Center, and a Shakespeare specialty bookstall. In 2017, a new, innovative S omething Borrowed, Something New: performance venue, The Yard at Chicago Shakespeare, expanded CST's Shakespeare’s Sources 18 campus to include three theaters. The year-round, flexible venue can 1606 and All That 19 be configured in a variety of shapes and sizes with audience capacities Shakespeare, Tragedy, and Us 21 ranging from 150 to 850, defining the audience-artist relationship to best serve each production. Now in its thirty-second season, the Theater has Scholars' Perspectives produced nearly the entire Shakespeare canon: All’s Well That Ends -

Durham Research Online

Durham Research Online Deposited in DRO: 28 June 2018 Version of attached le: Submitted Version Peer-review status of attached le: Peer-reviewed Citation for published item: Atkinson, S. (2016) 'Care, kidneys and clones : the distance of space, time and imagination.', in The Edinburgh companion to the critical medical humanities. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press., pp. 611-626. Edinburgh companions to literature and the humanities. Further information on publisher's website: https://edinburghuniversitypress.com/book-the-edinburgh-companion-to-the-critical-medical-humanities.html Publisher's copyright statement: Additional information: Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in DRO • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full DRO policy for further details. Durham University Library, Stockton Road, Durham DH1 3LY, United Kingdom Tel : +44 (0)191 334 3042 | Fax : +44 (0)191 334 2971 https://dro.dur.ac.uk Care, Kidneys and Clones: the distance of space, time and imagination Sarah Atkinson Department of Geography and the Centre for Medical Humanities, Durham University ‘We lived, as usual by ignoring. Ignoring isn't the same as ignorance, you have to work at it.’ (Margaret Atwood in The Handmaid’s Tale)1 Care as a concept is central to any engagement with health, ill-health and the practices that aim to prevent, mitigate or cure, and the term itself is mobilised in a variety of different ways and at a variety of different scales. -

1 Name___KEY___Date___Macbeth: Act

Name_____KEY_____ Date_____________ Macbeth: Act V Reading and Study Guide I. Vocabulary: Be able to define the following words and understand them when they appear in the play. Also, be prepared to be quizzed on these words. perturb: disturb, bother taper: candle note: our word taper that means to make gradually smaller (e.g., to taper someone off a medicine) probably comes from the sense of a taper (candle) gradually diminishing in size as it burns. guise: outward appearance note: think of the word disguise fortify: to strengthen pester: to annoy hew: to cut down abhor: hate, detest; to reject something very strongly Etymology: ab (away) + horror (to tremble; shudder) The word literally means to shrink back (away) in horror (trembling). Word is stronger than hate. II. Background Info: Moirai (3 Fates): In Greek Mythology, these are the three sisters who have the power to decide man’s destiny. The first of the sisters (Clotho) spun the thread of a person’s life and decided what the life would be like. The second (Lachesis) measured the thread of life. She decided how long it would be. The third (Atropos) is the one who cut the thread of life. Essentially, these three sisters determined the length of each person’s life as well as how much suffering. Their names in Roman Mythology are Nona, Decuma, and Morta. And Norse Mythology also has three goddesses of destiny. The exact details of these three goddesses differ in different stories and pieces of art. Most of our information comes from Hesiod’s Theogeny, although there are references in Homer’s Iliad and Plato’s Republic. -

GUARDIANS of AMERICAN LETTERS Roster As of February 2021

GUARDIANS OF AMERICAN LETTERS roster as of February 2021 An Anonymous Gift in honor of those who have been inspired by the impassioned writings of James Baldwin James Baldwin: Collected Essays In honor of Daniel Aaron Ralph Waldo Emerson: Collected Poems & Translations Charles Ackerman Richard Wright: Early Novels Arthur F. and Alice E. Adams Foundation Reporting World War II, Part II, in memory of Pfc. Paul Cauley Clark, U.S.M.C. The Civil War: The Third Year Told By Those Who Lived It, in memory of William B. Warren J. Aron Charitable Foundation Richard Henry Dana, Jr.: Two Years Before the Mast & Other Voyages, in memory of Jack Aron Reporting Vietnam: American Journalism 1959–1975, Parts I & II, in honor of the men and women who served in the War in Vietnam Vincent Astor Foundation, in honor of Brooke Astor Henry Adams: Novels: Mont Saint Michel, The Education Matthew Bacho H. P. Lovecraft: Tales Bay Foundation and Paul Foundation, in memory of Daniel A. Demarest Henry James: Novels 1881–1886 Frederick and Candace Beinecke Edgar Allan Poe: Poetry & Tales Edgar Allan Poe: Essays & Reviews Frank A. Bennack Jr. and Mary Lake Polan James Baldwin: Early Novels & Stories The Berkley Family Foundation American Speeches: Political Oratory from the Revolution to the Civil War American Speeches: Political Oratory from Abraham Lincoln to Bill Clinton The Civil War: The First Year Told By Those Who Lived It The Civil War: The Second Year Told By Those Who Lived It The Civil War: The Final Year Told By Those Who Lived It Ralph Waldo Emerson: Selected -

Narrative Topography: Fictions of Country, City, and Suburb in the Work of Virginia Woolf, W. G. Sebald, Kazuo Ishiguro, and Ian Mcewan

Narrative Topography: Fictions of Country, City, and Suburb in the Work of Virginia Woolf, W. G. Sebald, Kazuo Ishiguro, and Ian McEwan Elizabeth Andrews McArthur Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2012 © 2012 Elizabeth Andrews McArthur All rights reserved ABSTRACT Narrative Topography: Fictions of Country, City, and Suburb in the Work of Virginia Woolf, W. G. Sebald, Kazuo Ishiguro, and Ian McEwan Elizabeth Andrews McArthur This dissertation analyzes how twentieth- and early twenty-first- century novelists respond to the English landscape through their presentation of narrative and their experiments with novelistic form. Opening with a discussion of the English planning movement, “Narrative Topography” reveals how shifting perceptions of the structure of English space affect the content and form of the contemporary novel. The first chapter investigates literary responses to the English landscape between the World Wars, a period characterized by rapid suburban growth. It reveals how Virginia Woolf, in Mrs. Dalloway and Between the Acts, reconsiders which narrative choices might be appropriate for mobilizing and critiquing arguments about the relationship between city, country, and suburb. The following chapters focus on responses to the English landscape during the present era. The second chapter argues that W. G. Sebald, in The Rings of Saturn, constructs rural Norfolk and Suffolk as containing landscapes of horror—spaces riddled with sinkholes that lead his narrator to think about near and distant acts of violence. As Sebald intimates that this forms a porous “landscape” in its own right, he draws attention to the fallibility of representation and the erosion of cultural memory. -

Life and Truth in Ishiguro's Never Let Me Go

Life and Truth in Ishiguro’s Never Let Me Go Bernadette Waterman Ward* ABSTRACT: Showing us a society in which questions about life issues cannot be asked, non-Christian Kazuo Ishiguro’s Never Let Me Go vivifies the prophetic observations of Evangelium vitae. Ishiguro immerses readers in the interrelation of technological threats to the family and to undefended lives. Despair rises from untruths about family and sexuality. The protagonists surrender to homicidal and suicidal meaninglessness. Both texts preach the sacredness of every being that comes from human ancestry, powerfully indicting the passion for power in biotechnology that overshadows the truth inscribed in the body. Although the novel makes the truths of Evangelium vitae painfully vivid, almost all its critics evade attending to the interrelated life issues in a way that curiously echoes the very accusation about complicity and falsehood that is at the heart of the novel’s cultural critique. AZUO ISHIGURO’S Never Let Me Go puts readers into peculiar sympathy with its narrator.1 We like and empathize with Kathy H., as she narrates Kher upbringing with others like herself: clones manufactured for what they call “donations” of organs. Placid, compassionate, sensitive and intelligent, she is enmeshed in a bureaucracy that condemns her, and her only friends, to be dismembered for parts by medical professionals. Unlike George Orwell’s 1984, which was set in a future into which we might descend if we did not take heed, Ishiguro’s novel is not warning us of what might happen or what could happen. He sets the novel in the 1990s, with close-grained social detail, and with only one alteration in technology: that cloning has allowed for the production of human individuals. -

Remembering World War Ii in the Late 1990S

REMEMBERING WORLD WAR II IN THE LATE 1990S: A CASE OF PROSTHETIC MEMORY By JONATHAN MONROE BULLINGER A dissertation submitted to the Graduate School-New Brunswick Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Program in Communication, Information, and Library Studies Written under the direction of Dr. Susan Keith and approved by Dr. Melissa Aronczyk ________________________________________ Dr. Jack Bratich _____________________________________________ Dr. Susan Keith ______________________________________________ Dr. Yael Zerubavel ___________________________________________ New Brunswick, New Jersey January 2017 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Remembering World War II in the Late 1990s: A Case of Prosthetic Memory JONATHAN MONROE BULLINGER Dissertation Director: Dr. Susan Keith This dissertation analyzes the late 1990s US remembrance of World War II utilizing Alison Landsberg’s (2004) concept of prosthetic memory. Building upon previous scholarship regarding World War II and memory (Beidler, 1998; Wood, 2006; Bodnar, 2010; Ramsay, 2015), this dissertation analyzes key works including Saving Private Ryan (1998), The Greatest Generation (1998), The Thin Red Line (1998), Medal of Honor (1999), Band of Brothers (2001), Call of Duty (2003), and The Pacific (2010) in order to better understand the version of World War II promulgated by Stephen E. Ambrose, Tom Brokaw, Steven Spielberg, and Tom Hanks. Arguing that this time period and its World War II representations