Engleski, Pdf (104

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Place of the Guitar in the Musical History of Yugoslavia

Guitar Compositions from Yugoslavia volume I Copyright © Syukhtun Editions 2002 THE PLACE OF THE GUITAR IN THE MUSICAL HISTORY OF YUGOSLAVIA Uroš Dojcinovic Prologue A phenomenon increasingly present in the contemporary music of the former Yugoslav republics is the guitar. It is by no means an exaggeration to say that today a large part of the creative and interpretative work being done in our music is focused on the expressive possiblities of this plucked-string instrument. The classical guitar has already had such a long history in all the ex-Yugoslav republics, that no one would deny the esteemed place that it now occupies. On the contrary, the exploitation and appreciation of the guitar still are enjoying a marked upswing, despite the tragic developments in the 1990s which finally caused the collapse of Yugoslavia. But before taking a brief look at the guitar history of the former Yugoslavia, I feel the necessity of summarizing the general history of the area which is the subject of this volume. Prior to 1918, various foreign influences were imposed on the region of the Balkan peninsula which was later to form the nation of Yugoslavia. These influences also included oppression by the various foreign authorities. The idea of Yugoslav union was first born during the 19th century along with the appearance of economic contact with Europe. In October of l918 Croatia separated from the Austro- Hungarian Empire, and during the Croatian Congress proclaimed the SCS-state (Serbia-Croatia-Slovenia). Along with Croatia, Serbia and Slovenia, the state was later joined by Bosnia, Hercegovina, Montenegro and Vojvodina. -

The Impact of the Illyrian Movement on the Croatian Lexicon

Slavistische Beiträge ∙ Band 223 (eBook - Digi20-Retro) George Thomas The Impact of the Illyrian Movement on the Croatian Lexicon Verlag Otto Sagner München ∙ Berlin ∙ Washington D.C. Digitalisiert im Rahmen der Kooperation mit dem DFG-Projekt „Digi20“ der Bayerischen Staatsbibliothek, München. OCR-Bearbeitung und Erstellung des eBooks durch den Verlag Otto Sagner: http://verlag.kubon-sagner.de © bei Verlag Otto Sagner. Eine Verwertung oder Weitergabe der Texte und Abbildungen, insbesondere durch Vervielfältigung, ist ohne vorherige schriftliche Genehmigung des Verlages unzulässig. «Verlag Otto Sagner» ist ein Imprint der Kubon & Sagner GmbH. George Thomas - 9783954792177 Downloaded from PubFactory at 01/10/2019 04:08:27AM via free access 00050383 S lavistische B e it r ä g e BEGRÜNDET VON ALOIS SCHMAUS HERAUSGEGEBEN VON HEINRICH KUNSTMANN PETER REHDER • JOSEF SCHRENK REDAKTION PETER REHDER Band 223 VERLAG OTTO SAGNER MÜNCHEN George Thomas - 9783954792177 Downloaded from PubFactory at 01/10/2019 04:08:27AM via free access 00050383 GEORGE THOMAS THE IMPACT OF THEJLLYRIAN MOVEMENT ON THE CROATIAN LEXICON VERLAG OTTO SAGNER • MÜNCHEN 1988 George Thomas - 9783954792177 Downloaded from PubFactory at 01/10/2019 04:08:27AM via free access ( B*y«ftecne I Staatsbibliothek l Mönchen ISBN 3-87690-392-0 © Verlag Otto Sagner, München 1988 Abteilung der Firma Kubon & Sagner, GeorgeMünchen Thomas - 9783954792177 Downloaded from PubFactory at 01/10/2019 04:08:27AM via free access 00050383 FOR MARGARET George Thomas - 9783954792177 Downloaded from PubFactory at 01/10/2019 04:08:27AM via free access .11 ж ־ י* rs*!! № ri. ur George Thomas - 9783954792177 Downloaded from PubFactory at 01/10/2019 04:08:27AM via free access 00050383 Preface My original intention was to write a book on caiques in Serbo-Croatian. -

Svetozar Borevic, South Slav Habsburg Nationalism, and the First World War

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 4-17-2021 Fuer Kaiser und Heimat: Svetozar Borevic, South Slav Habsburg Nationalism, and the First World War Sean Krummerich University of South Florida Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the History Commons Scholar Commons Citation Krummerich, Sean, "Fuer Kaiser und Heimat: Svetozar Borevic, South Slav Habsburg Nationalism, and the First World War" (2021). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/8808 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Für Kaiser und Heimat: Svetozar Boroević, South Slav Habsburg Nationalism, and the First World War by Sean Krummerich A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History College of Arts & Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: Kees Boterbloem, Ph.D. Darcie Fontaine, Ph.D. J. Scott Perry, Ph.D. Golfo Alexopoulos, Ph.D. Date of Approval: March 30, 2021 Keywords: Serb, Croat, nationality, identity, Austria-Hungary Copyright © 2021, Sean Krummerich DEDICATION For continually inspiring me to press onward, I dedicate this work to my boys, John Michael and Riley. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This dissertation would not have been possible without the support of a score of individuals over more years than I would care to admit. First and foremost, my thanks go to Kees Boterbloem, Darcie Fontaine, Golfo Alexopoulos, and Scott Perry, whose invaluable feedback was crucial in shaping this work into what it is today. -

Matija Majar Ziljski Enlightener, Politician, Scholar

MATIJA MAJAR ZILJSKI ENLIGHTENER, POLITICIAN, SCHOLAR ISKRA VASILJEVNA ČURKINA Matija Majar Ziljski left a significant mark in differ- Matija Majar je bistveno zaznamoval različna po- ent spheres of cultural, educational and political life. dročja kulturnega, vzgojnega in političnega življenja. During the revolution of 1848–1849, he was an Slo- Med revolucijo 1848–1849 je bil eden vodilnih slo- venian ideologist and the first to publish his political venskih mislecev in prvi, ki je objavil politični pro- program entitled United Slovenia. After the revolu- gram Zedinjena Slovenija. Po revoluciji se je postopo- tion, he gradually turned away from Pan-Slovenian ma preusmeril od vseslovenskih vprašanj v ustvarjanje affairs, the main reason for this being his idea about panslovanskega/vseslovanskega jezika. Ta usmeritev se creation of Pan-Slavic literary language. His posi- je še bolj okrepila po njegovem potovanju na Etnograf- tion on this matter strengthened after his trip to the sko razstavo v Moskvo leta 1867 in zaradi prijatelj- Ethnographic Exhibition in Moscow in 1867 and his stev z ruskimi slavofili. friendship with Russian Slavophiles. Ključne besede: Matija Majar Ziljski, biografija, Keywords: Matija Majar Ziljski, biography, Panslav- panslavizem, etnografska razstava, Moskva. ism, Ethnographic exhibition, Moscow. Matija Majar Ziljski was one of the most outstanding Slovenian national activists of the 19th century� He was born on 7 February 1809 in a small village of Wittenig- Vitenče in the Gail-Zilja river valley� His father, a -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI • University Microfilms International A Bell & Howell Information Company 3 0 0 North) Z e e b Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 4 8 1 0 6 -1 3 4 6 U SA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 Order Number 9121692 Poetics andkultura: A study of contemporary Slovene and Croat puppetry Latchis-Silverthorne, Eugenie T., Ph.D. -

The Croatian Ustasha Regime and Its Policies Towards

THE IDEOLOGY OF NATION AND RACE: THE CROATIAN USTASHA REGIME AND ITS POLICIES TOWARD MINORITIES IN THE INDEPENDENT STATE OF CROATIA, 1941-1945. NEVENKO BARTULIN A thesis submitted in fulfilment Of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of New South Wales November 2006 1 2 3 Acknowledgements I would like to thank my supervisor Dr. Nicholas Doumanis, lecturer in the School of History at the University of New South Wales (UNSW), Sydney, Australia, for the valuable guidance, advice and suggestions that he has provided me in the course of the writing of this thesis. Thanks also go to his colleague, and my co-supervisor, Günther Minnerup, as well as to Dr. Milan Vojkovi, who also read this thesis. I further owe a great deal of gratitude to the rest of the academic and administrative staff of the School of History at UNSW, and especially to my fellow research students, in particular, Matthew Fitzpatrick, Susie Protschky and Sally Cove, for all their help, support and companionship. Thanks are also due to the staff of the Department of History at the University of Zagreb (Sveuilište u Zagrebu), particularly prof. dr. sc. Ivo Goldstein, and to the staff of the Croatian State Archive (Hrvatski državni arhiv) and the National and University Library (Nacionalna i sveuilišna knjižnica) in Zagreb, for the assistance they provided me during my research trip to Croatia in 2004. I must also thank the University of Zagreb’s Office for International Relations (Ured za meunarodnu suradnju) for the accommodation made available to me during my research trip. -

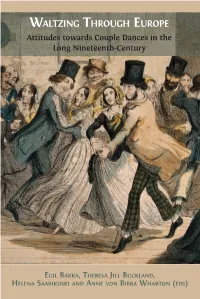

9. Dancing and Politics in Croatia: the Salonsko Kolo As a Patriotic Response to the Waltz1 Ivana Katarinčić and Iva Niemčić

WALTZING THROUGH EUROPE B ALTZING HROUGH UROPE Attitudes towards Couple Dances in the AKKA W T E Long Nineteenth-Century Attitudes towards Couple Dances in the Long Nineteenth-Century EDITED BY EGIL BAKKA, THERESA JILL BUCKLAND, al. et HELENA SAARIKOSKI AND ANNE VON BIBRA WHARTON From ‘folk devils’ to ballroom dancers, this volume explores the changing recep� on of fashionable couple dances in Europe from the eighteenth century onwards. A refreshing interven� on in dance studies, this book brings together elements of historiography, cultural memory, folklore, and dance across compara� vely narrow but W markedly heterogeneous locali� es. Rooted in inves� ga� ons of o� en newly discovered primary sources, the essays aff ord many opportuni� es to compare sociocultural and ALTZING poli� cal reac� ons to the arrival and prac� ce of popular rota� ng couple dances, such as the Waltz and the Polka. Leading contributors provide a transna� onal and aff ec� ve lens onto strikingly diverse topics, ranging from the evolu� on of roman� c couple dances in Croa� a, and Strauss’s visits to Hamburg and Altona in the 1830s, to dance as a tool of T cultural preserva� on and expression in twen� eth-century Finland. HROUGH Waltzing Through Europe creates openings for fresh collabora� ons in dance historiography and cultural history across fi elds and genres. It is essen� al reading for researchers of dance in central and northern Europe, while also appealing to the general reader who wants to learn more about the vibrant histories of these familiar dance forms. E As with all Open Book publica� ons, this en� re book is available to read for free on the UROPE publisher’s website. -

“Entire Yugoslavia, One Courtyard.” Political Mythology, Brotherhood and Unity and the “Non-National” Yugoslavness at the Sarajevo School of Rock

"All Yugoslavia Is Dancing Rock and Roll" Yugoslavness and the Sense of Community in the 1980s Yu-Rock Jovanovic, Zlatko Publication date: 2014 Document version Early version, also known as pre-print Citation for published version (APA): Jovanovic, Z. (2014). "All Yugoslavia Is Dancing Rock and Roll": Yugoslavness and the Sense of Community in the 1980s Yu-Rock. Det Humanistiske Fakultet, Københavns Universitet. Download date: 24. sep.. 2021 FACULTY OF HUMANITIE S UNIVERSITY OF COPENH AGEN PhD thesis Zlatko Jovanovic “ All Yugoslavia Is Dancing Rock and Roll” Yugoslavness and the Sense of Community in the 1980s Yu-Rock Academic advisor: Mogens Pelt Submitted: 25/11/13 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................. 4 Relevant Literature and the Thesis’ Contribution to the Field .................................................................................... 6 Theoretical and methodological considerations ........................................................................................................... 12 Sources ............................................................................................................................................................................. 19 The content and the methodology of presentation ....................................................................................................... 22 YUGOSLAVS, YUGOSLAVISM AND THE NOTION OF YUGOSLAV-NESS .................. 28 Who Were the Yugoslavs? “The -

1 Bibliografija – Bibliography 1969- , Arti Musices

1 BIBLIOGRAFIJA – BIBLIOGRAPHY 1969- , ARTI MUSICES ARTI MUSICES HRVATSKI MUZIKOLOŠKI ZBORNIK CROATIAN MUSICOLOGICAL REVIEW BIBLIOGRAFIJA - BIBLIOGRAPHY (1969- ) IZVORNI ZNANSTVENI ČLANCI / ORIGINAL SCIENTIFIC PAPERS; PRETHODNA PRIOPĆENJA / PRELIMINARY PAPERS; KRATKA PRIOPĆENJA / SHORT PAPERS, STRUČNI ČLANCI / EXPERT PAPERS, PREGLEDNI ČLANCI / REVIEW PAPERS, REFERATI / CONFERENCE PAPERS, SAŽECI MAGISTARSKIH I DOKTORSKIH RADOVA U MUZIKOLOGIJI / SUMMARIES OF M.A. AND Ph.D. THESES IN MUSICOLOGY, RECENZIJE, PRIKAZI, INFORMACIJE O PUBLIKACIJAMA / REVIEWS AND INFORMATION ON PUBLICATIONS, IZVJEŠTAJI / REPORTS, GRAĐA ZA POVIJEST HRVATSKE GLAZBE / DATA FOR HISTORY OF CROATIAN MUSIC, HRVATSKA GLAZBENA TERMINOLOGIJA / CROATIAN MUSICAL TERMINOLOGY, MISCELLANEA, INTERVJU / INTERVIEW, RASPRAVE / DISCUSSIONS, BIBLIOGRAFIJE/DISKOGRAFIJE / BIBLIOGRAPHIES/DISCOGRAPHIES PRVI MUZIKOLOŠKI KORACI / FIRST MUSICOLOGICAL STEPS 2 BIBLIOGRAFIJA – BIBLIOGRAPHY 1969- , ARTI MUSICES 1. IZVORNI ZNANSTVENI ČLANCI – ORIGINAL SCIENTIFIC PAPERS ANDREIS, Josip: Albertijev «Dijalog». O 350-godišnjici objavljivanja (Summary: Giorgio Alberti's Dialogue – 350th Anniversary), 1 (1969) 91-104. ANDREIS, Josip: Glazba u Hrvatskoj enciklopediji s kraja prošlog stoljeća (Summary: Music in the Croatian Encyclopaedia at the End of the 19th Century; Zusammenfassung: Musik in der Kroatischen Enzyklopädie vom Ende des 19. Jahrhunderts), 13/1 (1982) 11-16. ANDREIS, Josip: Musicology in Croatia, Sp. issue 1 (1970) 7-45. ANDREIS, Josip: Muzikologija u Hrvatskoj u razdoblju -

Yugoslavia | International Encyclopedia of the First World War

Version 1.0 | Last updated 18 July 2016 Yugoslavia By Ljubinka Trgovčević The idea for the unification of the Southern Slavs emerged in the 19th century and the strength of its appeal varied over the course of its development. During the First World War, unification became the main war aim of the government of the Kingdom of Serbia as well as the Yugoslav Committee. In different ways, these two groups advocated for Yugoslav unification, resulting in the creation of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes at the end of the war. Table of Contents 1 Introduction 2 Early ideas about the Unification of Southern Slavs 3 Triune Croatian Kingdom 4 On the Eve of War 5 Unity as a War Aim: 1914-1918 6 Montenegrin and Yugoslav Unity 7 Conclusion Notes Selected Bibliography Citation Introduction The origins of Yugoslavism, or the idea of the cultural and political unification of the Southern Slavs (“jug”, i.e.Y ug means “south”) can be traced back to the 1830s and the emergence of the Illyrian movement. At that time, a group of Croatian intellectuals, in order to resist the Magyarisation and Germanisation carried out by the Habsburg Monarchy, developed a program which aimed, on the one hand, to unify Croats and, on the other hand, to gather Southern Slavs into a single cultural and ethnic entity. During the 19th century, Southern Slavs lived in the large, multinational Habsburg and Ottoman empires as well as in Serbia and Montenegro, which had emerged as small, independent nation-states by 1878. Croats envisioned their unification either within the Habsburg Monarchy as the Triune Croatian Kingdom or within the framework of an independent Southern Slav state; the Slovenes took a similar position. -

The Invention of Musical Illyrism

Prejeto / received: 19. 1. 2016. Odobreno / accepted: 3. 2. 2016 THE INVENTION OF MUSICAL ILLYRISM STANISLAV TUKSAR Hrvatska akademija znanosti i umjetnosti Izvleček: Star rimski izraz »Illiricum«, ki ga je Abstract: The ancient Roman term “Illyricum”, Katoliška cerkev v 17. stoletju uporabljala za pro- reintroduced by the Catholic Church in the vince Dalmacija, Hrvaška, Bosna in Slavonija, seventeenth century to denote the provinces of so ideologi hrvaškega narodnopreporodnega Dalmatia, Croatia, Bosnia and Slavonia, was gibanja »ponovno izumili« v tridesetih letih 19. “re-invented” by the ideologists of the Croatian stoletja kot nadnacionalni konstrukt. Izraz so National Revival movement in the 1830s as a v glasbi na Hrvaškem v 19. stoletju uporabljali supra-national construct. It was also used in tudi številni skladatelji, izvajalci, muzikologi, music by many composers, performers and občinstvo in mediji. musicologists, as well as broader audiences and public media in nineteenth-century Croatia. Ključne besede: ilirizem, Hrvaška, južnoslovan- Keywords: Illyrism, Croatia, South Slavic area, sko področje, glasba, koncept »kulturni narod«. music, “cultural-national” concept. In identifying the idea of “Illyrism” as applied in nineteenth-century Croatian musical culture, it seems useful to first present the genesis of the term itself and its usage in both Croatian and South-Slavic, as well as in the broader regional cultural and social history. In this, the long temporal development in its construction manifests a multi-layered character, unveiling the complex parallel structure of its sometimes elusive and vague denotations and meanings. It is well known that the term itself, mostly in the form of the noun “Illyricum” (→ Illyria Romana, Illyria Barbara), was used in ancient Rome to geographically denote its province from 167 BC to 10 AD along the eastern shores of the Adriatic Sea and its hinterlands.1 Between AD 10 and 35 Roman administrators dissolved the province of Illyricum and divided its lands between the new provinces of Pannonia and Dalmatia. -

De Musica Disserenda Letnik/Year XII Št./No

MUZIKOLOŠKI INŠTITUT ZNANSTVENORAZISKOVALNI CENTER SAZU De musica disserenda Letnik/Year XII Št./No. 1 2016 Ljubljana 2016 DMD_12_TXT_FIN.indd 1 7. 06. 2016 12:16:44 De musica disserenda ISSN 1854-3405 © 2016, Muzikološki inštitut ZRC SAZU Izdajatelj / Publisher: Muzikološki inštitut ZRC SAZU Mednarodni uredniški svet / International advisory board: Zdravko Blažeković (New York), Bojan Bujić (Oxford), Ivano Cavallini (Palermo), Marc Desmet (Saint-Etienne), Janez Matičič (Ljubljana), Andrej Rijavec (Ljubljana), Stanislav Tuksar (Zagreb) Uredniški odbor / Editorial board: Matjaž Barbo, Nataša Cigoj Krstulović, Metoda Kokole, Jurij Snoj, Katarina Šter Glavni in odgovorni urednik / Editor-in-chief: Jurij Snoj Urednika De musica disserenda XII/1/ Editors of De musica disserenda XII/1: Nataša Cigoj Krstulović, Ivano Cavallini Naslov uredništva / Editorial board address: Muzikološki inštitut ZRC SAZU, Novi trg 2, p. p. 306, 1001 Ljubljana, Slovenija E-pošta / E-mail: [email protected] Tel. / Phone: +386 1 470 61 97 http://mi.zrc-sazu.si Revija izhaja s podporo Javne agencije za Raziskovalno dejavnost RS. The journal is sponsored by the Slovenian Research Agency. Cena posamezne številke / Single issue price: 6 € Letna naročnina / Annual subscription: 10 € Naročila sprejema / Orders should be sent to: Založba ZRC, p. p. 306, 1001 Ljubljana, Slovenija E-pošta / E-mail: [email protected] Tel. / Phone: +386 1 470 64 64 Tisk / Printed by: Collegium graphicum, d. o. o., Ljubljana Naklada / Printrun: 150 De musica disserenda je muzikološka znanstvena revija, ki objavlja znanstvene razprave s področja muzikologije ter z muzikologijo povezanih interdisciplinarnih področij. Izhaja dvakrat letno. Vsi prispevki so anonimno recenzirani. Revija je v celoti vključena v Open Journal System in besedila dostopna tudi v dLib.si.