Mcdowell Title Page

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The 2021 Guide to Manuscript Publishers

Publish Authors Emily Harstone Authors Publish The 2021 Guide to Manuscript Publishers 230 Traditional Publishers No Agent Required Emily Harstone This book is copyright 2021 Authors Publish Magazine. Do not distribute. Corrections, complaints, compliments, criticisms? Contact [email protected] More Books from Emily Harstone The Authors Publish Guide to Manuscript Submission Submit, Publish, Repeat: How to Publish Your Creative Writing in Literary Journals The Authors Publish Guide to Memoir Writing and Publishing The Authors Publish Guide to Children’s and Young Adult Publishing Courses & Workshops from Authors Publish Workshop: Manuscript Publishing for Novelists Workshop: Submit, Publish, Repeat The Novel Writing Workshop With Emily Harstone The Flash Fiction Workshop With Ella Peary Free Lectures from The Writers Workshop at Authors Publish The First Twenty Pages: How to Win Over Agents, Editors, and Readers in 20 Pages Taming the Wild Beast: Making Inspiration Work For You Writing from Dreams: Finding the Flashpoint for Compelling Poems and Stories Table of Contents Table of Contents .......................................................................................................... 5 Introduction ................................................................................................................. 13 Nonfiction Publishers.................................................................................................. 19 Arcade Publishing .................................................................................................. -

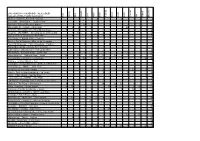

Template EUROVISION 2021

Write the names of the players in the boxes 1 to 4 (if there are more, print several times) - Cross out the countries that have not reached the final - Vote with values from 1 to 12, or any others that you agree - Make the sum of votes in the "TOTAL" column - The player who has given the highest score to the winning country will win, and in case of a tie, to the following - Check if summing your votes you’ve given the highest score to the winning country. GOOD LUCK! 1 2 3 4 TOTAL Anxhela Peristeri “Karma” Albania Montaigne “ Technicolour” Australia Vincent Bueno “Amen” Austria Efendi “Mata Hari” Azerbaijan Hooverphonic “ The Wrong Place” Belgium Victoria “Growing Up is Getting Old” Bulgaria Albina “Tick Tock” Croatia Elena Tsagkrinou “El diablo” Cyprus Benny Christo “ Omaga “ Czech Fyr & Flamme “Øve os på hinanden” Denmark Uku Suviste “The lucky one” Estonia Blind Channel “Dark Side” Finland Barbara Pravi “Voilà” France Tornike Kipiani “You” Georgia Jendrick “I Don’t Feel Hate” Germany Stefania “Last Dance” Greece Daði og Gagnamagnið “10 Years” Island Leslie Roy “ Maps ” Irland Eden Alene “Set Me Free” Israel 1 2 3 4 TOTAL Maneskin “Zitti e buoni” Italy Samantha Tina “The Moon Is Rising” Latvia The Roop “Discoteque” Lithuania Destiny “Je me casse” Malta Natalia Gordienko “ Sugar ” Moldova Vasil “Here I Stand” Macedonia Tix “Fallen Angel” Norwey RAFAL “The Ride” Poland The Black Mamba “Love is on my side” Portugal Roxen “ Amnesia “ Romania Manizha “Russian Woman” Russia Senhit “ Adrenalina “ San Marino Hurricane “LOCO LOCO” Serbia Ana Soklic “Amen” Slovenia Blas Cantó “Voy a quedarme” Spain Tusse “ Voices “ Sweden Gjon’s Tears “Tout L’Univers” Switzerland Jeangu Macrooy “ Birth of a new age” The Netherlands Go_A ‘Shum’ Ukraine James Newman “ Embers “ United Kingdom. -

Oral History Interview with Nell Sinton, 1974 August 15

Oral History interview with Nell Sinton, 1974 August 15 Funding for the digital preservation of this interview was provided by a grant from the Save America's Treasures Program of the National Park Service. Contact Information Reference Department Archives of American Art Smithsonian Institution Washington. D.C. 20560 www.aaa.si.edu/askus Transcript Preface The following oral history transcript is the result of a recorded interview with Nell Walter Sinton on August 15, 1974. The interview took place in San Francisco, California, and was conducted by Paul J. Karlstrom for the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. The Archives of American Art has reviewed the transcript and has made corrections and emendations. This transcript has been lightly edited for readability by the Archives of American Art. The reader should bear in mind that they are reading a transcript of spoken, rather than written, prose. Interview PAUL J. KARLSTROM: Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, a conversation with Nell Sinton at her home in San Francisco on August 15, 1974. [Audio Break.] NELL W. SINTON: I feel that way very strongly, because of the total blank about my grandparents back then— not total, but—there's a picture of the house in Germany. PAUL J. KARLSTROM: [Inaudible.] NELL W. SINTON: Yes. It was a picture of the house in Germany. I don't even know how my grandfather got here, whether he came around the Cape of Good Hope, I mean, Cape Horn. I don't think he came in a covered wagon, but I know that he came in the 1850s. -

Mcdowell Title Page

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title House Work: Domesticity, Belonging, and Salvage in the Art of Jess, 1955-1991 Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/5mf693nb Author McDowell, Tara Publication Date 2013 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California House Work: Domesticity, Belonging, and Salvage in the Art of Jess, 1955-1991 By Tara Cooke McDowell A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History of Art in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Emerita Anne M. Wagner, Chair Professor Emeritus T.J. Clark Professor Emerita Kaja Silverman Spring 2013 Abstract House Work: Domesticity, Belonging, and Salvage in the Art of Jess, 1955-1991 by Tara McDowell Doctor of Philosophy in History of Art University of California, Berkeley Professor Emerita Anne M. Wagner, Chair This dissertation examines the work of the San Francisco-based artist Jess (1923-2004). Jess’s multimedia and cross-disciplinary practice, which takes the form of collage, assemblage, drawing, painting, film, illustration, and poetry, offers a perspective from which to consider a matrix of issues integral to the American postwar period. These include domestic space and labor; alternative family structures; myth, rationalism, and excess; and the salvage and use of images in the atomic age. The dissertation has a second protagonist, Robert Duncan (1919-1988), preeminent American poet and Jess’s partner and primary interlocutor for nearly forty years. Duncan and Jess built a household and a world together that transgressed boundaries between poetry and painting, past and present, and acknowledged the limits and possibilities of living and making daily. -

Focusfall07.Pdf

Table of Contents ADVENTURE . 1 REFERENCE . 12 BIRDING . 1 SCIENCE . 13 CHILDREN’S . 1-5 SPORTS . 14-15 Living Creatures . 3 TRAVEL . 16-17 Sports . 4 US HISTORY. 18-20 US History . 4-5 WRITING. 21 ECOLOGY . 5 Nature Writing . 21 HEALTHY LIVING . 6-10 Travel Writing . 21 Martial Arts . 9-10 YOGA. 21 NAUTICAL. 10 OUTDOOR & NATURE. 10-12 Living Creatures . 12 Ordering Information New Accounts, For accounts wishing to be Established Accounts Canadian Orders Sales Representatives serviced by the New York Order Dept. and Inquiries & General Information sales staff call: Random House, Inc. Random House of Canada, Inc. Random House, Inc. Phone: 212-572-2328 Attn: Order Entry Diversified Sales Special Markets Fax: 212-572-4961 400 Hahn Road 2775 Matheson Blvd. East 1745 Broadway Specialty Wholesale: Westminster, MD 21157 Mississauga, ON L4W 4P4 6th Floor If you are distributing to a Phone: 800-733-3000 Phone: 800-668-4247 New York, NY 10019 specialty retailer please call: Fax: 800-659-2436 Fax: 905-624-6217 E-mail orders to: Phone: 888-591-1200, x2 [email protected] Fax: 212-572-4961 Customer Service International Sales and Credit Depts. Random House, Inc. Specialty Retail: Premium Sales: Phone: 1-800-733-3000 International Division For accounts wishing to be Phone: 800-800-3246 serviced by a field rep call Fax: 212-572-4961 Price and availability are subject 1745 Broadway to change without notice. our Field Sales Department: 6th Floor Phone: 800-729-2960 New York, NY 10019 Fax: 800-292-9071 Phone: 212-829-6712 E-mail orders to: Fax: 212-829-6700 [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] Our Specialty Retail Field Representatives Anne McGilvray Krikorian Miller Associates Portfolio Ted Weinstein And & Company 978-465-7377 212-685-7377 The Company He Keeps 312-321-0710 (Chicago) CT, MA, ME, NH, NY, RI, VT NY (Metro and Westchester) 503-222-5105 (Zips 120-125/127-149) 952-932-7153 (Minnetonka) NJ (Excluding Southern tip) AK, ID, OR, WA AR, KS, IL, IN, LA, MO, MN, Lines By Alan Green N. -

![Montaigne's Unknown God and Melville's Confidence-Man -In Memoriam]Ohn Spencer Hill (1943-1998)](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7141/montaignes-unknown-god-and-melvilles-confidence-man-in-memoriam-ohn-spencer-hill-1943-1998-977141.webp)

Montaigne's Unknown God and Melville's Confidence-Man -In Memoriam]Ohn Spencer Hill (1943-1998)

CAMILLE R. LA Bossr:ERE The World Revolves Upon an I: Montaigne's Unknown God and Melville's Confidence-Man -in memoriam]ohn Spencer Hill (1943-1998) Les mestis qui ont ... le cul entre deux selles, desquels je suis ... I The mongrel! sorte, of which I am one ... sit betweene two stooles -Michel de Montaigne, "Des vaines subtilitez" I "Of Vaine Subtilties" Deus est anima brutorum. -Oliver Goldsmith, "The Logicians Refuted" YEA AND NAY EACH HATH HIS SAY: BUT GOD HE KEEPS THF MTDDT.F WAY -Herman Melville, "The Conflict of Convictions" T ATE-MODERN SCHOLARLY accounts of Montaigne and his L oeuvre attest to the still elusive, beguilingly ironic character of his humanism. On the one hand, the author of the Essais has in vited recognition as "a critic of humanism, as part of a 'Counter Renaissance'."' The wry upending of such vanity as Protagoras served to model for Montaigne-"Truely Protagoras told us prettie tales, when he makes man the measure of all things, who never knew so much as his owne," according to the famous sentence 1 Peter Burke, Montaigne (Oxford: Oxford UP, 1981) 11. 340 • THE DALHOUSIE REvlEW from the "Apologie of Raimond Sebond"2-naturally comes to mind when he is thought of in this way (Burke 12). On the other hand, Montaigne has been no less justifiably recognized by a long line of twentieth-century commentators3 as a major contributor to the progress of an enduring philosophy "qui fait de l'homme, selon la tradition antique, la valeur premiere et vise a son plein epa nouissement. -

The Board of Library Trustees May Act on Any Item on This Agenda

PLEASE NOTE: Special Starting BERKELEY PUBLIC LIBRARY Time BOARD OF LIBRARY TRUSTEES Regular Meeting AGENDA South BRANCH February 10, 2010 6:30 p.m. 1901 Russell Street The Board of Library Trustees may act on any item on this agenda. I. PRELIMINARY MATTERS A. Call to Order B. Public Comments (6:00 – 6:30 p.m.) (Proposed 30-minute time limit, with speakers allowed 3 minutes each) C. Report from library employees and unions, discussion of staff issues Comments / responses to reports and issues addressed in packet. D. Report from Board of Library Trustees E. Approval of Agenda II. PRESENTATIONS A. Measure FF South Branch Library Update 1. Presentation by Field Paoli Architects on the Schematic Design Phase; and Staff Report on the Process, Community Input and Next Steps. 2. Public Comment (on this item only) 3. Board discussion B. Measure FF Claremont Branch Library Update 1. Presentation by Gould Evans Baum Thornley Architects on the Schematic Design Phase; and Staff Report on the Process, Community Input and Next Steps. 2. Public Comment (on this item only) 3. Board discussion C. Measure FF West Branch Library Update 1. Review presentation made by Harley Ellis Devereaux/GreenWorks Studio on the Conceptual Design Phase; and Staff Report on the Process, Community Input and Next Steps at February 6, 2010 Special BOLT meeting. Refer to February 6, 2010 Agenda Packet. Notes and comments from the meeting to be delivered. 2. Public Comment (on this item only) 3. Board discussion III. CONSENT CALENDAR The Board will consider removal and addition of items to the Consent Calendar prior to voting on the Consent Calendar. -

P E Ti Is Tv Á N O Rs I L Á S Z Ló L E V I a Ttila B E Tti P . R O B I

n e i s l b ó l e m n l i i o i i z u a f o z i i á i t s l b s t i t R ESC HUNGARY RAJONGÓI TALÁLKOZÓ c b s v ó s i v z t t t r s o e t e . r i s a á e s m 2021-08-28 HELYSZÍNI SZAVAZÁS P I O L L A B P E Z R T I P Ö Albánia – Anxhela Peristeri – Karma 3 2 1 3 9 Ausztrália – Montaigne – Technicolour 5 5 Ausztria – Vincent Bueno – Amen 10 2 2 14 Azerbajdzsán – Efendi – Mata Hari 1 1 5 8 7 10 6 38 Belgium – Hooverphonic – The Wrong Place 6 4 3 6 19 Bulgária – VICTORIA – Growing Up Is Getting Old 7 10 7 7 6 4 41 Ciprus – Elena Tsagrinou – El Diablo 3 4 3 3 4 3 2 22 Csehország – Benny Cristo – omaga 0 Dánia – Fyr & Flamme – Øve os på hinanden 1 1 Egyesült Királyság – James Newman – Embers 5 6 1 12 Észak-Macedónia – Vasil – Here I Stand 0 Észtország – Uku Suviste – The Lucky One 7 4 11 Finnország – Blind Channel – Dark Side 2 2 8 12 Franciaország – Barbara Pravi – Voilà 10 12 12 12 12 12 4 3 2 79 Görögország – Stefania – Last Dance 12 4 5 2 6 10 39 Grúzia – Tornike Kipiani – You 0 Hollandia – Jeangu Macrooy – Birth of a New Age 8 7 4 19 Horvátország – Albina – Tick-Tock 7 2 8 17 Írország – Lesley Roy – Maps 2 5 12 8 27 Izland – Daði og Gagnamagnið – 10 Years 7 6 3 5 1 22 Izrael – Eden Alene – Set Me Free 1 3 2 6 Lengyelország – RAFAŁ – The Ride 8 7 15 Lettország – Samanta Tīna – The Moon Is Rising 1 1 Litvánia – The Roop – Discoteque 4 5 8 10 10 10 4 51 Málta – Destiny – Je me casse 8 10 12 4 6 10 50 Moldova – Natalia Gordienko – Sugar 5 10 8 23 Németország – Jendrik – I Don’t Feel Hate 0 Norvégia – TIX – Fallen Angel 0 Olaszország – Måneskin -

View Prospectus

Archive from “A Secret Location” Small Press / Mimeograph Revolution, 1940s–1970s We are pleased to offer for sale a captivating and important research collection of little magazines and other printed materials that represent, chronicle, and document the proliferation of avant-garde, underground small press publications from the forties to the seventies. The starting point for this collection, “A Secret Location on the Lower East Side,” is the acclaimed New York Public Library exhibition and catalog from 1998, curated by Steve Clay and Rodney Phillips, which documented a period of intense innovation and experimentation in American writing and literary publishing by exploring the small press and mimeograph revolutions. The present collection came into being after the owner “became obsessed with the secretive nature of the works contained in the exhibition’s catalog.” Using the book as a guide, he assembled a singular library that contains many of the rare and fragile little magazines featured in the NYPL exhibition while adding important ancillary material, much of it from a West Coast perspective. Left to right: Bill Margolis, Eileen Kaufman, Bob Kaufman, and unidentified man printing the first issue of Beatitude. [Ref SL p. 81]. George Herms letter ca. late 90s relating to collecting and archiving magazines and documents from the period of the Mimeograph Revolution. Small press publications from the forties through the seventies have increasingly captured the interest of scholars, archivists, curators, poets and collectors over the past two decades. They provide bedrock primary source information for research, analysis, and exhibition and reveal little known aspects of recent cultural activity. The Archive from “A Secret Location” was collected by a reclusive New Jersey inventor and offers a rare glimpse into the diversity of poetic doings and material production that is the Small Press Revolution. -

Born 1923, Long Beach, CA Died 2004, San Francisco, CA Jess Was

JESS Born 1923, Long Beach, CA Died 2004, San Francisco, CA Jess was born Burgess Franklin Collins in Long Beach, California. He was drafted into the military and worked on the production of plutonium for the Manhattan Project. After his discharge in 1946, Jess worked at the Hanford Atomic Energy Project in Richland, Washington, and painted in his spare time, but his dismay at the threat of atomic weapons led him to abandon his scientific career and focus on his art. In 1949, Jess enrolled in the California School of the Arts (now the San Francisco Art Institute) and, after breaking with his family, began referring to himself simply as “Jess”. He met Robert Duncan in 1951 and began a relationship with the poet that lasted until Duncan’s death in 1988. In 1952, in San Francisco, Jess, with Duncan and painter Harry Jacobus, opened the King Ubu Gallery, which became an important venue for alternative art and which remained so when, in 1954, poet Jack Spicer reopened the space as the Six Gallery. Many of Jess’s paintings and collages have themes drawn from chemistry, alchemy, the occult, and male beauty, including a series called Translations (1959–1976) which is done with heavily laid-on paint in a paint-by-number style. In 1975, the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art displayed six of the “Translations” paintings in their MATRIX 2 exhibition.[1] Collins also created elaborate collages using old book illustrations and comic strips (particularly, the strip Dick Tracy, which he used to make his own strip Tricky Cad). -

Y Ii; I I It Jvv ; Jj

V. n HI" i 1 1 i s: i tirfVMMUV.u tit 13 ;it h ti if ii 'J: : ,H S M I if 41 11 I! ii V y ii; i i it jvV ; jj... p VOL. VI.-- NO. 54. HONOLULU, HAWAIIAN ISLANDS, SATURDAY, MARCH 5, L887. PRICE 5 CENTS. THE DAILY dvcrfisenunls. Mvtrtistmtnte. acific Commercial Advertiser ATTORXETS-AT-LA- W. INTER-ISLAN- D IS PUBLISHED ROYAL INSURANCE COMP'Y 8. STAXLET, JOBX BPHVANCK. Oo. CUkBZXCK W. VOUN'KT T Spruanco, Stanley & Co., Every Morning Except Sundays. Steam Navigation A8HFOBD. ASHFOBD. OF LIVERPOOL. Importers and Jobbers of Fine iLIMITKD. Ash ford & Ashford, ATTORNEYS, COUNSEIXORS, eOLICITORS, WHISKIES, WINES and LIQUORS Claus Spreckela UNION FEED CO,, ADVOCATES, ETC. MUCSCRIPTIONS : Wm. a. Irwta. CAPITAL 10.000.000 410 Front St., San Francifceo. t STEAMER W. Q. HALL, IMPOBTER3 CS&LBBS OlHce Honolulu Halo, adjoining the Pos 2 tf Aw Dailv i . Advertises, oiie voar $s oo Office. 42dtwtf Duly P. C. advestiseb, six months 3 00 UNLIMITED LIABILITY. M ALULA N I,) In Daily I'. C. Advertiser, three months i 50 C. MAIN. E. I WINCHESTER Duly I C. , " ! Advektiskr, i r ninr.rh 50 CLAUS & CO., BATES Com ma ude HAT AND Wekki.y I, c. Advkktise t, v(.,,r 5 SPRECKELS GRAIN, JOHN T. DARE, i" h- 0" 01 riptlou & fign f Insurance nil Will run resular.y to Manlaea, Maul, nd Kona Main .Subscription, V. I', a. ' :''; I?lre be effected at Moderate defRates of Prem Telephone 175. Wim ziester, - f. No. postage) fi . aud Kti.u, UaivKil, Ml um, by the undersigned. -

Adventuring with Books: a Booklist for Pre-K-Grade 6. the NCTE Booklist

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 311 453 CS 212 097 AUTHOR Jett-Simpson, Mary, Ed. TITLE Adventuring with Books: A Booklist for Pre-K-Grade 6. Ninth Edition. The NCTE Booklist Series. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, Ill. REPORT NO ISBN-0-8141-0078-3 PUB DATE 89 NOTE 570p.; Prepared by the Committee on the Elementary School Booklist of the National Council of Teachers of English. For earlier edition, see ED 264 588. AVAILABLE FROMNational Council of Teachers of English, 1111 Kenyon Rd., Urbana, IL 61801 (Stock No. 00783-3020; $12.95 member, $16.50 nonmember). PUB TYPE Books (010) -- Reference Materials - Bibliographies (131) EDRS PRICE MF02/PC23 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Annotated Bibliographies; Art; Athletics; Biographies; *Books; *Childress Literature; Elementary Education; Fantasy; Fiction; Nonfiction; Poetry; Preschool Education; *Reading Materials; Recreational Reading; Sciences; Social Studies IDENTIFIERS Historical Fiction; *Trade Books ABSTRACT Intended to provide teachers with a list of recently published books recommended for children, this annotated booklist cites titles of children's trade books selected for their literary and artistic quality. The annotations in the booklist include a critical statement about each book as well as a brief description of the content, and--where appropriate--information about quality and composition of illustrations. Some 1,800 titles are included in this publication; they were selected from approximately 8,000 children's books published in the United States between 1985 and 1989 and are divided into the following categories: (1) books for babies and toddlers, (2) basic concept books, (3) wordless picture books, (4) language and reading, (5) poetry. (6) classics, (7) traditional literature, (8) fantasy,(9) science fiction, (10) contemporary realistic fiction, (11) historical fiction, (12) biography, (13) social studies, (14) science and mathematics, (15) fine arts, (16) crafts and hobbies, (17) sports and games, and (18) holidays.