Volume 2 Issue 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

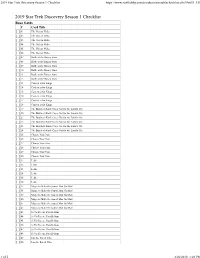

2019 Star Trek Discovery Season 1 Checklist

2019 Star Trek Discovery Season 1 Checklist https://www.scifihobby.com/products/printablechecklist.cfm?SetID=355 2019 Star Trek Discovery Season 1 Checklist Base Cards # Card Title [ ] 01 The Vulcan Hello [ ] 02 The Vulcan Hello [ ] 03 The Vulcan Hello [ ] 04 The Vulcan Hello [ ] 05 The Vulcan Hello [ ] 06 The Vulcan Hello [ ] 07 Battle at the Binary Stars [ ] 08 Battle at the Binary Stars [ ] 09 Battle at the Binary Stars [ ] 10 Battle at the Binary Stars [ ] 11 Battle at the Binary Stars [ ] 12 Battle at the Binary Stars [ ] 13 Context is for Kings [ ] 14 Context is for Kings [ ] 15 Context is for Kings [ ] 16 Context is for Kings [ ] 17 Context is for Kings [ ] 18 Context is for Kings [ ] 19 The Butcher's Knife Cares Not for the Lamb's Cry [ ] 20 The Butcher's Knife Cares Not for the Lamb's Cry [ ] 21 The Butcher's Knife Cares Not for the Lamb's Cry [ ] 22 The Butcher's Knife Cares Not for the Lamb's Cry [ ] 23 The Butcher's Knife Cares Not for the Lamb's Cry [ ] 24 The Butcher's Knife Cares Not for the Lamb's Cry [ ] 25 Choose Your Pain [ ] 26 Choose Your Pain [ ] 27 Choose Your Pain [ ] 28 Choose Your Pain [ ] 29 Choose Your Pain [ ] 30 Choose Your Pain [ ] 31 Lethe [ ] 32 Lethe [ ] 33 Lethe [ ] 34 Lethe [ ] 35 Lethe [ ] 36 Lethe [ ] 37 Magic to Make the Sanest Man Go Mad [ ] 38 Magic to Make the Sanest Man Go Mad [ ] 39 Magic to Make the Sanest Man Go Mad [ ] 40 Magic to Make the Sanest Man Go Mad [ ] 41 Magic to Make the Sanest Man Go Mad [ ] 42 Magic to Make the Sanest Man Go Mad [ ] 43 Si Vis Pacem, Para Bellum [ ] 44 Si Vis Pacem, -

Cyberpunking a Library

Cyberpunking a Library Collection assessment and collection Leanna Jantzi, Neil MacDonald, Samantha Sinanan LIBR 580 Instructor: Simon Neame April 8, 2010 “A year here and he still dreamed of cyberspace, hope fading nightly. All the speed he took, all the turns he’d taken and the corners he’d cut in Night City, and he’d still see the matrix in his sleep, bright lattices of logic unfolding across that colorless void.” – Neuromancer, William Gibson 2 Table of Contents Table of Contents ................................................................................................................................................ 2 Introduction ......................................................................................................................................................... 3 Description of Subject ....................................................................................................................................... 3 History of Cyberpunk .................................................................................................................................................... 3 Themes and Common Motifs....................................................................................................................................... 3 Key subject headings and Call number range ....................................................................................................... 4 Description of Library and Community ..................................................................................................... -

A Very Short History of Cyberpunk

A Very Short History of Cyberpunk Marcus Janni Pivato Many people seem to think that William Gibson invented The cyberpunk genre in 1984, but in fact the cyberpunk aesthetic was alive well before Neuromancer (1984). For example, in my opinion, Ridley Scott's 1982 movie, Blade Runner, captures the quintessence of the cyberpunk aesthetic: a juxtaposition of high technology with social decay as a troubling allegory of the relationship between humanity and machines ---in particular, artificially intelligent machines. I believe the aesthetic of the movie originates from Scott's own vision, because I didn't really find it in the Philip K. Dick's novel, Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep (1968), upon which the movie is (very loosely) based. Neuromancer made a big splash not because it was the "first" cyberpunk novel, but rather, because it perfectly captured the Zeitgeist of anxiety and wonder that prevailed at the dawning of the present era of globalized economics, digital telecommunications, and exponential technological progress --things which we now take for granted but which, in the early 1980s were still new and frightening. For example, Gibson's novels exhibit a fascination with the "Japanification" of Western culture --then a major concern, but now a forgotten and laughable anxiety. This is also visible in the futuristic Los Angeles of Scott’s Blade Runner. Another early cyberpunk author is K.W. Jeter, whose imaginative and disturbing novels Dr. Adder (1984) and The Glass Hammer (1985) exemplify the dark underside of the genre. Some people also identify Rudy Rucker and Bruce Sterling as progenitors of cyberpunk. -

Hugo Award -- Britannica Online Encyclopedia

10/10/2017 Hugo Award -- Britannica Online Encyclopedia Hugo Award Hugo Award, any of several annual awards presented by the World Science Fiction Society (WSFS). The awards are granted for notable achievement in science �ction or science fantasy. Established in 1953, the Hugo Awards were named in honour of Hugo Gernsback, founder of Amazing Stories, the �rst magazine exclusively for science �ction. Hugo Award. This particular award was given at MidAmeriCon II, in Kansas City, Missouri, on August … Michi Trota Pin, in the form of the rocket on the Hugo Award, that is given to the finalists. Michi Trota Hugo Awards https://www.britannica.com/print/article/1055018 1/10 10/10/2017 Hugo Award -- Britannica Online Encyclopedia year category* title author 1946 novel The Mule Isaac Asimov (awarded in 1996) novella "Animal Farm" George Orwell novelette "First Contact" Murray Leinster short story "Uncommon Sense" Hal Clement 1951 novel Farmer in the Sky Robert A. Heinlein (awarded in 2001) novella "The Man Who Sold the Moon" Robert A. Heinlein novelette "The Little Black Bag" C.M. Kornbluth short story "To Serve Man" Damon Knight 1953 novel The Demolished Man Alfred Bester 1954 novel Fahrenheit 451 Ray Bradbury (awarded in 2004) novella "A Case of Conscience" James Blish novelette "Earthman, Come Home" James Blish short story "The Nine Billion Names of God" Arthur C. Clarke 1955 novel They’d Rather Be Right Mark Clifton and Frank Riley novelette "The Darfsteller" Walter M. Miller, Jr. short story "Allamagoosa" Eric Frank Russell 1956 novel Double Star Robert A. Heinlein novelette "Exploration Team" Murray Leinster short story "The Star" Arthur C. -

Irish Gothic Fiction

THE ‘If the Gothic emerges in the shadows cast by modernity and its pasts, Ireland proved EME an unhappy haunting ground for the new genre. In this incisive study, Jarlath Killeen shows how the struggle of the Anglican establishment between competing myths of civility and barbarism in eighteenth-century Ireland defined itself repeatedly in terms R The Emergence of of the excesses of Gothic form.’ GENCE Luke Gibbons, National University of Ireland (Maynooth), author of Gaelic Gothic ‘A work of passion and precision which explains why and how Ireland has been not only a background site but also a major imaginative source of Gothic writing. IRISH GOTHIC Jarlath Killeen moves well beyond narrowly political readings of Irish Gothic by OF IRISH GOTHIC using the form as a way of narrating the history of the Anglican faith in Ireland. He reintroduces many forgotten old books into the debate, thereby making some of the more familiar texts seem suddenly strange and definitely troubling. With FICTION his characteristic blend of intellectual audacity and scholarly rigour, he reminds us that each text from previous centuries was written at the mercy of its immediate moment as a crucial intervention in a developing debate – and by this brilliant HIST ORY, O RIGI NS,THE ORIES historicising of the material he indicates a way forward for Gothic amidst the ruins of post-Tiger Ireland.’ Declan Kiberd, University of Notre Dame Provides a new account of the emergence of Irish Gothic fiction in the mid-eighteenth century FI This new study provides a robustly theorised and thoroughly historicised account of CTI the beginnings of Irish Gothic fiction, maps the theoretical terrain covered by other critics, and puts forward a new history of the emergence of the genre in Ireland. -

BLADE RUNNER 2049 “I Can Only Make So Many.” – Niander Wallace REPLICANT SPRING ROLLS

BLADE RUNNER 2049 “I can only make so many.” – Niander Wallace REPLICANT SPRING ROLLS INGREDIENTS • 1/2 lb. shrimp Dipping Sauce: • 1/2 lb. pork tenderloin • 2 tbsp. oil • Green leaf lettuce • 2 tbsp. minced garlic • Mint & cilantro leaves • 8 tbsp. hoisin sauce • Chives • 2-3 tbsp. smooth peanut butter • Carrot cut into very thin batons • 1 cup water • Rice paper — banh trang • Sriracha • Rice vermicelli — the starchless variety • Peanuts • 1 tsp salt • 1 tsp sugar TECHNICOLOR | MPC FILM INSTRUCTIONS • Cook pork in water, salt and sugar until no longer pink in center. Remove from water and allow to cool completely. • Clean and cook shrimp in boiling salt water. Remove shells and any remaining veins. Split in half along body and slice pork very thinly. Boil water for noodles. • Cook noodles for 8 mins plunge into cold water to stop the cooking. Drain and set aside. • Wash vegetables and spin dry. • Put warm water in a plate and dip rice paper. Approx. 5-10 seconds. Removed slightly before desired softness so you can handle it. Layer ingredients starting with lettuce and mint leaves and ending with shrimp and carrot batons. Tuck sides in and roll tightly. Dipping Sauce: • Cook minced garlic until fragrant. Add remaining ingredients and bring to boil. Remove from heat and garnish with chopped peanuts and cilantro. BLADE RUNNER 2049 “Things were simpler then.” – Agent K DECKARD’S FAVORITE SPICY THAI NOODLES INGREDIENTS • 1 lb. rice noodles • 1/2 cup low sodium soy sauce • 2 tbsp. olive oil • 1 tsp sriracha (or to taste) • 2 eggs lightly beaten • 2 inches fresh ginger grated • 1/2 tbsp. -

The Original Series, Star Trek: the Next Generation, and Star Trek: Discovery

Gender and Racial Identity in Star Trek: The Original Series, Star Trek: The Next Generation, and Star Trek: Discovery Hannah van Geffen S1530801 MA thesis - Literary Studies: English Literature and Culture Dr. E.J. van Leeuwen Dr. M.S. Newton 6 July, 2018 van Geffen, ii Table of Contents Introduction............................................................................................................................. 1 1. Notions of Gender and Racial Identity in Post-War American Society............................. 5 1.1. Gender and Racial Identity in the Era of Star Trek: The Original Series........... 6 1.2. Gender and Racial Identity in the Era of Star Trek: The Next Generation......... 10 1.3. Gender and Racial Identity in the Era of Star Trek: Discovery........................... 17 2. Star Trek: The Original Series........................................................................................... 22 2.1. The Inferior and Objectified Position of Women in Star Trek............................ 23 2.1.1. Subordinate Portrayal of Voluptuous Vina........................................... 23 2.1.2. Less Dependent, Still Sexualized Portrayal of Yeoman Janice Rand.. 25 2.1.3. Interracial Star Trek: Captain Kirk and Nyota Uhura.......................... 26 2.2. The Racial Struggle for Equality in Star Trek..................................................... 28 2.2.1. Collaborating With Mr. Spock: Accepting the Other........................... 28 3. Star Trek: The Next Generation........................................................................................ -

Packet 6.Pdf

Saturnalia: Packet 6 Edited by Justine French, Avinash Iyer, Laurence Li, Robert Condron, Connor Mayers, Eric Yin, Karan Gurazada, Nick Dai, Ethan Ashbrook, Dylan Bowman, Jeffrey Ma, Daniel Ma, Benjamin McAvoy-Bickford, and Lalit Maharjan. Written by the editors and Vikshar Athreya, Maxwell Ye, Felix Wang, Danny Kim, William Orr, Jason Lewis, Tiffany Zhou, Gabe Forrest, Ariel Faeder, Josh Rollin, Louis Li, Advaith Modali, Raymond Wang, Auden Young, Aadi Karthik, Ned Tagtmeier, Rohan Venkateswaran, Victor Li, and Richard Lin THESE TOSSUPS ARE PAIRED WITH BONUSES. IF A TOSSUP IS NOT CONVERTED, SKIP THE PAIRED BONUS AND MOVE ON TO THE NEXT TOSSUP. DO NOT COME BACK TO THE SKIPPED BONUS. 1. In his concerto for this instrument, Erich Wolfgang Korngold reused a two octave ascending theme from his film score for Another Dawn. A G minor “Canzonetta” is the middle movement of a D major concerto for this instrument inspired by Edouard Lalo’s concerto for it, the Symphonie Espagnole. Pyotr Tchaikovsky’s concerto for this instrument is in (*) D major. Joseph Joachim (“YO-zef YAW-kim”) was the dedicatee of a D major concerto for this string instrument composed by Johannes Brahms. For 10 points, name this highest-pitched string instrument played by Niccolo Paganini. ANSWER: violin [accept violin concerto] <Classical Music — Jeffrey Ma> [Edited] 1. Along with Liberal leaders Juan Álvarez and Ignacio Comonfort, this politician supported the Plan of Ayutla (“eye-YOOT-lah”). For 10 points each: [M] Name this president of Mexico from 1858 to 1872. The tenure of this first Mexican president of indigenous origin saw both the Reform War and the occupation of Mexico by the French under Emperor Maximilian I (“the first”). -

Modern Mythopoeia &The Construction of Fictional Futures In

Modern Mythopoeia & The Construction of Fictional Futures in Design Figure 1. Cassandra. Anthony Fredrick Augustus Sandys. 1904 2 Modern Mythopoeia & the Construction of Fictional Futures in Design Diana Simpson Hernandez MA Design Products Royal College of Art October 2012 Word Count: 10,459 3 INTRODUCTION: ON MYTH 10 SLEEPWALKERS 22 A PRECOG DREAM? 34 CONCLUSION: THE SLEEPER HAS AWAKEN 45 APPENDIX 77 BIBLIOGRAPHY 90 4 Figure 1. Cassandra. Anthony Fredrick Augustus Sandys. 1904. Available from: <http://culturepotion.blogspot.co.uk/2010/08/witches- and-witchcraft-in-art-history.html> [accessed 30 July 2012] Figure 2. Evidence Dolls. Dunne and Raby. 2005. Available from: <http://www.dunneandraby.co.uk/content/projects/69/0> [accessed 30 July 2012] Figure 3. Slave City-cradle to cradle. Atelier Van Lieshout. 2009. Available from: <http://www.designboom.com/weblog/cat/8/view/7862/atelier-van- lieshout-slave-city-cradle-to-cradle.html> [accessed 30 July 2012] Figure 4. Der Jude. 1943. Hans Schweitzer. Available from: <http://www.calvin.edu/academic/cas/gpa/posters2.htm> [accessed 15 September 2012] Figure 5. Lascaux cave painting depicting the Seven Sisters constellation. Available from: <http://madamepickwickartblog.com/2011/05/lascaux- and-intimate-with-the-godsbackstage-pass-only/> [accessed 05 July 2012] Figure 6. Map Presbiteri Johannis, Sive, Abissinorum Imperii Descriptio by Ortelius. Antwerp, 1573. Available from: <http://www.raremaps.com/gallery/detail/9021?view=print > [accessed 30 May 2012] 5 Figure 7. Mercator projection of the world between 82°S and 82°N. Available from: <http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mercator_projection> [accessed 05 July 2012] Figure 8. The Gall-Peters projection of the world map Available from: <http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gall–Peters_projection> [accessed 05 July 2012] Figure 9. -

Xavier Aldana Reyes, 'The Cultural Capital of the Gothic Horror

1 Originally published in/as: Xavier Aldana Reyes, ‘The Cultural Capital of the Gothic Horror Adaptation: The Case of Dario Argento’s The Phantom of the Opera and Dracula 3D’, Journal of Italian Cinema and Media Studies, 5.2 (2017), 229–44. DOI link: 10.1386/jicms.5.2.229_1 Title: ‘The Cultural Capital of the Gothic Horror Adaptation: The Case of Dario Argento’s The Phantom of the Opera and Dracula 3D’ Author: Xavier Aldana Reyes Affiliation: Manchester Metropolitan University Abstract: Dario Argento is the best-known living Italian horror director, but despite this his career is perceived to be at an all-time low. I propose that the nadir of Argento’s filmography coincides, in part, with his embrace of the gothic adaptation and that at least two of his late films, The Phantom of the Opera (1998) and Dracula 3D (2012), are born out of the tensions between his desire to achieve auteur status by choosing respectable and literary sources as his primary material and the bloody and excessive nature of the product that he has come to be known for. My contention is that to understand the role that these films play within the director’s oeuvre, as well as their negative reception among critics, it is crucial to consider how they negotiate the dichotomy between the positive critical discourse currently surrounding gothic cinema and the negative one applied to visceral horror. Keywords: Dario Argento, Gothic, adaptation, horror, cultural capital, auteurism, Dracula, Phantom of the Opera Dario Argento is, arguably, the best-known living Italian horror director. -

Mirrorshade Women: Feminism and Cyberpunk

Mirrorshade Women: Feminism and Cyberpunk at the Turn of the Twenty-first Century Carlen Lavigne McGill University, Montréal Department of Art History and Communication Studies February 2008 A thesis submitted to McGill University in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Communication Studies © Carlen Lavigne 2008 2 Abstract This study analyzes works of cyberpunk literature written between 1981 and 2005, and positions women’s cyberpunk as part of a larger cultural discussion of feminist issues. It traces the origins of the genre, reviews critical reactions, and subsequently outlines the ways in which women’s cyberpunk altered genre conventions in order to advance specifically feminist points of view. Novels are examined within their historical contexts; their content is compared to broader trends and controversies within contemporary feminism, and their themes are revealed to be visible reflections of feminist discourse at the end of the twentieth century. The study will ultimately make a case for the treatment of feminist cyberpunk as a unique vehicle for the examination of contemporary women’s issues, and for the analysis of feminist science fiction as a complex source of political ideas. Cette étude fait l’analyse d’ouvrages de littérature cyberpunk écrits entre 1981 et 2005, et situe la littérature féminine cyberpunk dans le contexte d’une discussion culturelle plus vaste des questions féministes. Elle établit les origines du genre, analyse les réactions culturelles et, par la suite, donne un aperçu des différentes manières dont la littérature féminine cyberpunk a transformé les usages du genre afin de promouvoir en particulier le point de vue féministe. -

TITLE AUTHOR SUBJECTS Adult Fiction Book Discussion Kits

Adult Fiction Book Discussion Kits Book Discussion Kits are designed for book clubs and other groups to read and discuss the same book. The kits include multiple copies of the book and a discussion guide. Some kits include Large Print copies (noted below in the subject area). Additional Large Print, CDbooks or DVDs may be added upon request, if available. The kit is checked out to one group member who is responsible for all the materials. Book Discussion Kits can be reserved in advance by calling the Adult Services Department, 314-994-3300 ext 2030. Kits may be picked up at any SLCL location, and should be returned inside the branch during normal business hours. To check out a kit, you’ll need a valid SLCL card. Kits are checked out for up to 8 weeks, and may not be renewed. Up to two kits may be checked out at one time to an individual. Customers will not receive a phone call or email when the kit is ready for pick up, so please note the pickup date requested. To search within this list when viewing it on a computer, press the Ctrl and F keys simultaneously, then type your search term (author, title, or subject) into the search box and press Enter. Use the arrow keys next to the search box to navigate to the matches. For a full plot summary, please click on the title, which links to the library catalog. New Book Discussion Kits are in bold red font, updated 11/19. TITLE AUTHOR SUBJECTS 1984 George Orwell science fiction/dystopias/totalitarianism Accident Chris Pavone suspense/spies/assassins/publishing/manuscripts/Large Print historical/women