A Translation of Octavia, a Latin Tragedy, with Notes and Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Donovan B.A., Cornell University, 2003

Literary and Ideological Memory in the Octavia by Lauren Marie Donovan B.A., Cornell University, 2003 A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Classics at Brown University PROVIDENCE, RHODE ISLAND MAY 2011 © Copyright 2011 by Lauren M. Donovan This dissertation by Lauren Marie Donovan is accepted in its present form by the Department of Classics as satisfying the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Date John Bodel, Advisor Recommended to the Graduate Council Date Shadi Bartsch, Reader Date Jeri DeBrohun, Reader Date Joseph Reed, Reader Approved by the Graduate Council Date Peter M. Weber, Dean of the Graduate School iii Curriculum Vitae Lauren Donovan was born in 1981 in Illinois, and spent her formative years in Concord, Massachusetts. She earned a B. A. summa cum laude in Classics from Cornell University in 2003, with a thesis titled “Ilia and Early Imperial Rome: The Roman Origin Legend in Text and Art” and received the Department of Classics prize in Latin upon graduation. Before beginning her graduate work at Brown University, Lauren taught Latin and Greek at the high school level for two years. During her graduate career, Lauren has presented talks on many topics including the idea of learnedness in Apuleius’ Metamorphoses, the role of Prometheus in Apollonius’ Argonautica, and various aspects of her dissertation work on the Octavia. She has also been the recipient of the Andrew W. Mellon Fellowship in Humanistic Studies (2005) and the Memoria Romana Dissertation Fellowship (2010). She is currently a visiting instructor at Wesleyan University. -

Notes on Seneca's Trojan Women for Vce Students

NOTES ON SENECA’S TROJAN WOMEN FOR VCE STUDENTS Betty Gabriel-Jones Seneca’s Trojan Women, is, like most of his plays, modelled on a Greek original, Eurip- ides’ Women of Troy. However, he brings a distinctly Roman attitude to his plays, an attitude no doubt at least partly formed by a life led in and around the courts of the Julio-Claudian emperors. Seneca thrived under Tiberius, fell out of favour with Caligula, returned to Rome on Caligula’s death, was exiled by Claudius, then recalled, became influential at the court of Nero (indeed was probably the second most powerful man in Rome, after the emperor) and was eventually sentenced to death by Nero. This eventful and, one assumes, stressful life surely played a part in his somewhat pessimistic view of life. It is hard to see how this could not be the case. After all, his protégé, Nero, murdered his own stepbrother, his stepsister/wife and his mother Agrippina. His second wife, whom he supposedly loved, he kicked to death in a drunken rage. Witnessing such events, even if one were not involved, would not lead one to see life as a sunny, cheerful affair. And Seneca was not uninvolved. He was no innocent, and may even have condoned the killing of Agrippina; certainly he composed a speech for Nero in which he justified his action. In addition to all this, Seneca lived in a Rome where bloody and murderous games were the staple entertainment of the masses. By philosophy, Seneca was a stoic—that is to say, he advised a life designed around ra- tional behaviour, modesty, and discipline. -

The Portrayal of Seneca in the Octavia and in Tacitus’ Annals

SYMBOLAE PHILOLOGORUM POSNANIENSIUM GRAECAE ET LATINAE XXVII/3 • 2017 pp. 169–187. ISSN 0302-7384 dOI: 10.14746/sppgl.2017.XXVII.3.11 JAkub Pigoń University of wrocław THE PORTRAYAL OF SENECA IN THE OCTAViA AND IN TACITUS’ ANNALs abstraCt. Pigoń Jakub, The Portrayal of Seneca in the Octavia and in Tacitus’ Annals The paper examines the representation of Seneca in two literary works of the late 1st and early 2nd centuries Ad, the anonymous tragedy Octavia and the Annals by Tacitus. In the Octavia Seneca appears as the emperor Nero’s upright but unhappy teacher trying in vain to inculcate salutary advice to his master. There is no question of his being responsible for the crimes of Nero; the picture of him drawn in the play is wholly favourable. The portrayal of Seneca in Tacitus’ Annals is more complex and nuanced, and only seldom does the historian give his own views about Nero’s advisor. However, it would be wrong to suppose that Seneca is harshly criticised by Tacitus. keywords: Seneca the Younger; Octavia praetexta; Tacitus; Nero; characterisation in literature; Roman literature (1st and 2nd cent. Ad); Roman Empire Seneca the Younger as a man, philosopher, statesman and writer, was judged by his contemporaries and posteriors in many various ways, arousing great emotions (both positive and negative) – and leaving few indifferent. I have written elsewhere about the way he was presented in the Roman literature of the Early Empire (from Seneca the Elder to Aulus Gellius).1 Here, I would like to take a closer look at two texts particularly important in the history of the early reception of Seneca – an unknown author’s tragedy Octavia (probably written right after Nero’s death in June 68 or in the 70s of the 1st century2), and Cornelius Tacitus’ historical work, the Annals (usually dated to the second decade of the 2nd century). -

Seneca: Apocolocyntosis Free

FREE SENECA: APOCOLOCYNTOSIS PDF Lucius Annaeus Seneca,P.T. Eden,P. E. Easterling,Philip Hardie,Richard Hunter,E. J. Kenney | 192 pages | 27 Apr 1984 | CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS | 9780521288361 | English | Cambridge, United Kingdom SENECA THE YOUNGER, Apocolocyntosis | Loeb Classical Library Rome,there have been published many other editions and also many translations. The following are specially noteworthy:. The English translation with accompanying largely plain text by W. Graves appended a translation to his Claudius the GodLondon The Satire of Seneca on the Apotheosis of Claudius. Ball, New York,has introduction, notes, and translation. Weinreich, Berlin, with German translation. Bibliographical surveys : M. Coffey, Seneca: Apocolocyntosis, Apocol. More Contact Us How to Subscribe. Search Publications Pages Publications Seneca: Apocolocyntosis. Advanced Search Help. Go To Section. Find in a Library View cloth edition. Print Email. Hide annotations Display: View facing pages View left- hand pages View right-hand pages Enter full screen mode. Eine Satire des Annaeus SenecaF. Buecheler, Symbola Philologorum Bonnensium. Leipzig, —Seneca: Apocolocyntosis. Petronii Saturae et liber Priapeorumed. Heraeus, ; and edition 6, revision and augmentation by W. Heraeus, Annaei Senecae Divi Claudii Apotheosis. Seneca: Apocolocyntosis, Bonn, Waltz, text and French translation and notes. Seneca, Apokolokyntosis Inzuccatura del divo Claudio. Text and Italian translation A. Rostagni, Seneca: Apocolocyntosis, Senecae Apokolokyntosis. Text, critical notes, and Italian translation. A Ronconi, Milan, Filologia Latina. Introduction, Seneca: Apocolocyntosis, and critical notes, Italian translation, and copious commentary, bibliography, and appendix. This work contains much information. A new text by P. Eden is expected. Sedgwick advises for various allusions to read also some account of Claudius. That advice indeed is good. -

Newton's Seneca: from Latin Fragments to Elizabethan Drama

Colby Quarterly Volume 26 Issue 2 June Article 4 June 1990 Newton's Seneca: From Latin Fragments to Elizabethan Drama Douglas E. Green Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/cq Recommended Citation Colby Quarterly, Volume 26, no.2, June 1990, p.87-95 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Colby. It has been accepted for inclusion in Colby Quarterly by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Colby. Green: Newton's Seneca: From Latin Fragments to Elizabethan Drama Newton I S Seneca: From Latin Fragments to Elizabethan Drama byDOUGLASE.GREEN s H. B. CHARLTON and many others have noted, firsthand experience ofGreek A tragedy was rare in Renaissance England. 1 It is no accident, then, that when Shakespeare wanted to parody the high style ofearly English tragedy, he drew on Seneca, at least indirectly, in the meter of his Elizabethan translators. Not surprisingly-especially in light of the prolonged agony of the hero in Seneca's Hercules Oetaeus-Bottom dies in "Ercles' vein" (MND I.ii.40)2: Come, tears, confound, Out, sword, and wound The pap of Pyramus; Ay, that left pap, Where heart doth hop. [Stabs himself] Thus die I, thus, thus, thus. Now am I dead, Now anl I fled; My soul is in the sky. Tongue, lose thy light, Moon, take thy flight, [Exit Moonshine.] Now die, die, die, die, die. [Dies.] (V.i.295-306) Seneca stood as virtually the sole classical model for tragedy-and perhaps mock-tragedy as well. Thus, along with the de casibus narrative tragedies and the moralities,3 Senecan drama reveals sonlething ofthe complex nature of"classi cal example" in the Renaissance. -

Condidit Suos Enses: Allusion to Vergil and Lucan in the Octavia It Has

Condidit suos enses: allusion to Vergil and Lucan in The Octavia It has long been noted that, during his dialogue with Seneca in the middle of The Octavia (Oct. 440—592), Nero virtually quotes the opening of Lucan’s Bellum Civile (Hosius 1922; Ferri 2003; Boyle 2008). Recently Boyle has also suggested that Nero’s use of the verb condere (Oct. 524), recalls the multifaceted use of the verb in Vergil’s Aeneid, especially at the epic’s end (Boyle 2008). In this paper I will argue that these intertexts are part of a wider and significant nexus of allusions to these two somewhat programmatic Julio-Claudian epics, and that a proper understanding of the famous dialogue between Nero and Seneca is in part predicated on how each character ‘reads’ these epics and their ideological underpinnings. As Seneca instructs Nero on the proper duties of kinship and Augustus’ rise to power (Oct.472-491), he rewrites the opening of the Aeneid with Augustus as its star, emphasizing what is now often called “the Augustan voice” of Vergil’s epic (Thomas 2001; Ganiban 2007). Augustus, like Aeneas, has been tossed about on land and sea by the hand of fate (illum tamen fortuna iactavit diu/ terra marique Oct.479-480; fato…ille et terris iactatus et alto Verg.A. 1.2-3). Both men suffered much at war (Oct. 480; Verg.A.1.5) and both undertook their toils in order to found something great: Aeneas founds the Roman race and a home for his gods (dum conderet urbem Verg.A.1.5), while Augustus pursues his enemies across the globe, weighed down by his pietas, so that he could refound the city once again (hostes parentis donec oppressit sui Oct.481). -

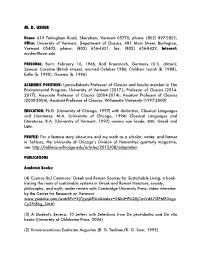

Mark User CV (PDF)

M. D. USHER Home: 619 Tottingham Road, Shoreham, Vermont 05770; phone: (802) 897-2822; Office: University of Vermont, Department of Classics, 481 Main Street, Burlington, Vermont 05405; phone: (802) 656-4431; fax: (802) 656-8429; Internet: [email protected] PERSONAL: Born: February 16, 1966, Bad Kreuznach, Germany (U.S. citizen); Spouse: Caroline (British citizen); married October 1986; Children: Isaiah (b. 1988), Estlin (b. 1990), Gawain (b. 1996) ACADEMIC POSITIONS: Lyman-Roberts Professor of Classics and faculty member in The Environmental Program, University of Vermont (2017-); Professor of Classics (2014- 2017); Associate Professor of Classics (2004-2014); Assistant Professor of Classics (2000-2004); Assistant Professor of Classics, Willamette University (1997-2000) EDUCATION: Ph.D. (University of Chicago, 1997) with distinction, Classical Languages and Literatures; M.A. (University of Chicago, 1994) Classical Languages and Literatures; B.A. (University of Vermont, 1992) summa cum laude, ΦΒΚ, Greek and Latin PROFILE: For a feature story about me and my work as a scholar, writer, and farmer in Tableau, the University of Chicago’s Division of Humanities quarterly magazine, see: http://tableau.uchicago.edu/articles/2013/08/adaptation. PUBLICATIONS Academic Books: (4) Cosmos [to] Commons: Greek and Roman Sources for Sustainable Living, a book tracing the roots of sustainable systems in Greek and Roman literature, society, philosophy, and myth, under review with Cambridge University Press; video interview by the Center for Research on Vermont: www.youtube.com/watch?v=Xj7yyqAPiUo&index=5&list=PLQXjCavV467GPMR3xge Cy2FL8bg_SirUt) (3) A Student's Seneca: 10 Letters with Selections from De providentia and De vita beata (University of Oklahoma Press, 2006) (2) Homerocentones Eudociae Augustae (B. -

Lucius Annaeus Seneca (Seneca the Younger)

LUCIUS ANNAEUS SENECA (SENECA THE YOUNGER) “NARRATIVE HISTORY” AMOUNTS TO FABULATION, THE REAL STUFF BEING MERE CHRONOLOGY “Stack of the Artist of Kouroo” Project Seneca the Younger HDT WHAT? INDEX SENECA THE YOUNGER SENECA THE YOUNGER 147 BCE August 4: On this date the comet that had passed by the sun on June 28th should have been closest to the earth, but we have no dated record of it being seen at this point. The only Western record of observation of this particular periodic comet is one that happens to come down to us by way of Seneca the Younger, of a bright reddish comet as big as the sun that had been seen after the death of the king of Syria, Demetrius, just a little while before the Greek Achaean war (which had begun in 146 BCE). ASTRONOMY HDT WHAT? INDEX SENECA THE YOUNGER SENECA THE YOUNGER 2 BCE At about this point Lucius Annaeus Seneca was born as the 2d son of a wealthy Roman family on the Iberian peninsula. The father, Seneca the Elder (circa 60BCE-37CE) had become famous as a teacher of rhetoric in Rome. An aunt would take the boy to Rome where he would be trained as an orator and educated in philosophy. In poor health, he would recuperate in the warmth of Egypt. SENECA THE YOUNGER HDT WHAT? INDEX SENECA THE YOUNGER SENECA THE YOUNGER 31 CE Lucius Aelius Sejanus was made a consul, and obtained the permission he has been requesting for a long time, to get married with Drusus’ widow Livilla. -

The Pseudo-Senecan Seneca on the Good Old Days: the Motif of the Golden Age in the Octavia

The Pseudo-Senecan Seneca on the Good Old Days: The Motif of the Golden Age in the Octavia Oliver Schwazer I. Introduction In his fabula praetexta entitled Octavia, the playwright stages the historical events that occurred during the reign of the last Julio-Claudian emperor in 62 CE.1 Following the divorce from his wife Octavia and re-marriage to another woman, Poppaea Sabina, the emperor gives the order for the former to be exiled. Neither a thorough dispute with his advisor Seneca2 nor the interventions of the pro-Octavia Chorus of Romans can deter Nero from his decision to put down the riots amongst the populace by using the sentence of Octavia as a warning.3 For a number of reasons, the Octavia has always been one of the most intriguing and in many ways most controversial pieces of Latin literature. While the fact that this play has been almost fully preserved can be regarded as extremely gratifying, not least because it stands in contrast to the number of praetextae known to us from no more than a few fragments, or even just one, it is particularly its textual transmission that has overshadowed scholarly dispute. Due to its sharp opposition to the eight mythological plays — excluding the Hercules Oetaeus of doubtful authorship — doubts have been raised about the assumption that the Octavia has been transmitted in manuscripts along with the tragedies now unanimously assigned to Seneca the Younger. To many researchers it seems inconceivable that the earlier advisor and later adversary of Nero would choose to appear as a dramatis persona on stage, particularly in a play where the contemporary emperor was presented in such a disreputable light. -

On Seneca, Mussato, Trevet and the Boethian "Tragedies"

Heliotropia 10.1-2 (2013) http://www.heliotropia.org On Seneca, Mussato, Trevet and the Boethian “Tragedies” of the De casibus hile good work has been done on the so-called Paduan prehu- manists since Billanovich put them in the critical spotlight half a W century ago,1 very little has subsequently been accomplished with regard to their influence on Boccaccio, especially his ideas on the relationship among poetry, philosophy and theology. I believe that there is a rich vein yet to be mined in this area, one that will aid us in understanding more profoundly not only his pre-Christian sources, which (always mediated, of course, by the influence of medieval interpretations) range broadly from the Pre-Socratics to Plato and Aristotle, to the Stoics and Neoplatonists, but also the way in which he creatively and convincingly interwove them into a tapestry of Christian doctrine. In other words, there is still something to be learned before we can confidently reconstruct his line, or lines, of humanistic thought. Unfortunately, it has become quite commonplace to think of Boccaccio’s defense of poetry in his final works as something that popped up almost spontaneously when, in reality, those pages actually depict a hypothesis of theologia poetica that evolved over a period of twenty-five years or so. Indeed, we may even say that his development of these holistic ideas, his attempts to unlock the wisdom of the ancients — whether enshrined in highly complex cosmological creations like the Calcidian Timaeus or simply glimpsed in flashes of literary brilliance in a handful of carefully chosen passages here and there — never really assumed a definitive form. -

Apocalypses and the Sage. Different Endings of the World in Seneca

ARTÍCULOS Gerión. Revista de Historia Antigua ISSN: 0213-0181 http://dx.doi.org/10.5209/GERI.63869 Apocalypses and the Sage. Different Endings of the World in Seneca Francesca Romana Berno1 Recibido: 9 de abril 2018 / Aceptado: 29 de octubre de 2018 Abstract. This paper deals with apocalypse, intended as a revelation or prediction related to the end of the world, in Seneca’s prose work. The descriptions and readings of this event appear to be quite different from each other. My analysis will follow two main directions. Firstly, I will show the human side of the question, focussing on the condition of the sage facing the universal ruin in the context of the macroscopic narrative structure of most passages, and on the differences between the Epicurean and the Stoic view on this point. Secondly, I will turn to the descriptions of the end of the world which we can find in the Naturales Quaestiones. I will argue that Seneca’s choice of flood or conflagration as representations for the apocalypse are not haphazard, but may be motivated by a subtle political narrative, and thus linked to the Stoic struggle for taking part in the governing of the state. In particular, the end of book three represents a flood which probably alludes toTiber’s floods. Keywords: Seneca; Final flood;ekpyrosis ; End of the world; Fire of Rome; Tiber’s flood. [esp] El sabio y los apocalipsis. Diferentes fines del mundo en Séneca Resumen. Este artículo trata del apocalipsis, entendido como una revelación o predicción relacionada con el fin del mundo, en las obras en prosa de Séneca. -

A Thirteenth-Century Manuscript of the Octavia

C. J. Herington: A thirteenth-century manuscript of the Octavia 353 man antworten müssen, daß dieser schon für die Quelle oder gar schon für die ihr vorausliegende überlieferung so wenig mehr aufhellbar oder auch nebensächlich war, daß man nicht eigens vermerkte, war u m die 17. Kohorte von Ostia nach Rom verlegt werden sollte. Das eine dürfen wir mit Sicherheit sagen: wenn die Quelle auch nur die Spur eines Hinweises darauf enthalten hätte, daß der Waffentransport mit der Mobilmachung Othos zusammenhing, hätte, um von allem anderen zu s<;hweigen, Tacitus kaum von einem par v u m initium (80,1) gesprochen. Wer! i. Westf. Heinz Heubner A THIRTEENTH-CENTURY MANUSCRIPT 1 OF THE OCTAVIA PRAETEXTA IN EXETER ) 1. DESCRIPTION AND HISTORY. Exeter Cathedral Library MS no. 3549 (B); vellum; assigned to the middle of the thirteenth century; 296 leaves (16 by 22. 5 cm.) in 26 irregular gatherings. The text (with one negligible exception) is written in the same hand through out, in double columns apart from the tragic items, which are in tripie columns. There are 53 lines to the column. The principal contents are Isidore's Etymologiae and other works, followed by the majority of the younger Seneca's prose writings. A complete list of these is given in the appen dix; but the body of the present anicle is devoted to the Octavia and the short excerpts from the other Senecim trage dies, which are found towards the end of the manuscript. Of the book's history little is known. It belonged to John de Grandisson, one of the greatest of Exeter's mediaeval bishops (born 1292, consecrated 1327, died 1369), but was to wander 1) The writer wishes particularly to thank the Librarian of the Cathe dral Library, Mrs.