'Tama Between Realms'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

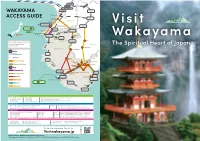

Wakayama Access Guide

WAKAYAMA ACCESS GUIDE Izumisano WAKAYAMA Pref. Buses between Koyasan and Ryujin Onsen run from April 1st to November 30th. Nanki-Shirahama Airport Tokyo 1h 20min TRAVEL BY TRAIN Kansai WIDE Area Pass 5 days validity https://www.westjr.co.jp/global/en/ticket/pass/kansai_wide/ Ise-Kumano Area Pass 5 days validity http://touristpass.jp/en/ise_kumano/ Kansai Thru Pass 2 days validity http://www.surutto.com/tickets/kansai_thru_english.html Kansai One Pass Rechargeable travel card https://kansaionepass.com/en/ TRAVEL BY AIR Haneda Airport (Tokyo) to Kansai International Airport (KIX) 1h 15min http://www.haneda-airport.jp/inter/en/ Haneda Airport (Tokyo) to Nanki-Shirahama Airport 1h 20min https://visitwakayama.jp/plan-your-trip/shirahama-airport/ JAL Explorer Pass (Aordable domestic fares with this pass from Japan Airlines) https://www.world.jal.co.jp/world/en/japan_explorer_pass/lp/ TRAVEL BY BUS Kansai International Airport (KIX) to Wakayama Limousine Bus 50min https://www.kansai-airport.or.jp/en/touristinfo/wakayama.html Kyoto to Shirahama Express Bus 4h https://visitwakayama.jp/itineraries/meiko-bus-osaka-kyoto/ Osaka to Shirahama Express Bus 3h 30min https://visitwakayama.jp/itineraries/meiko-bus-osaka-kyoto/ Tokyo to Shirahama Express Bus 12h https://visitwakayama.jp/itineraries/meiko-bus-tokyo/ Koyasan to Kumano (Daily between April 1 and November 30) Koyasan & Kumano Access Bus 4h 30min https://visitwakayama.jp/good-to-know/koyasan-kumano-bus/ TRAVEL BY CAR Times Car Rental https://www.timescar-rental.com/ Nissan Rent a Car https://nissan-rentacar.com/english/ -

Recent Developments in Local Railways in Japan Kiyohito Utsunomiya

Special Feature Recent Developments in Local Railways in Japan Kiyohito Utsunomiya Introduction National Railways (JNR) and its successor group of railway operators (the so-called JRs) in the late 1980s often became Japan has well-developed inter-city railway transport, as quasi-public railways funded in part by local government, exemplified by the shinkansen, as well as many commuter and those railways also faced management issues. As a railways in major urban areas. For these reasons, the overall result, approximately 670 km of track was closed between number of railway passengers is large and many railway 2000 and 2013. companies are managed as private-sector businesses However, a change in this trend has occurred in recent integrated with infrastructure. However, it will be no easy task years. Many lines still face closure, but the number of cases for private-sector operators to continue to run local railways where public support has rejuvenated local railways is sustainably into the future. rising and the drop in local railway users too is coming to a Outside major urban areas, the number of railway halt (Fig. 1). users is steadily decreasing in Japan amidst structural The next part of this article explains the system and changes, such as accelerating private vehicle ownership recent policy changes in Japan’s local railways, while and accompanying suburbanization, declining population, the third part introduces specific railways where new and declining birth rate. Local lines spun off from Japanese developments are being seen; the fourth part is a summary. Figure 1 Change in Local Railway Passenger Volumes (Unit: 10 Million Passengers) 55 50 45 Number of Passengers 40 35 30 1987 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 Fiscal Year Note: 70 companies excluding operators starting after FY1988 Source: Annual Report of Railway Statistics and Investigation by Railway Bureau Japan Railway & Transport Review No. -

Mie Aichi Shizuoka Nara Fukui Kyoto Hyogo Wakayama Osaka Shiga

SHIZUOKA AICHI MIE <G7 Ise-Shima Summit> Oigawa Railway Steam Locomotives 1 Toyohashi Park 5 The Museum Meiji-mura 9 Toyota Commemorative Museum of 13 Ise Grand Shrine 17 Toba 20 Shima (Kashikojima Island) 23 These steam locomotives, which ran in the This public park houses the remains of An outdoor museum which enables visitors to 1920s and 1930s, are still in fully working Yoshida Castle, which was built in the 16th experience old buildings and modes of Industry and Technology order. These stations which evoke the spirit century, other cultural institutions such as transport, mainly from the Meiji Period The Toyota Group has preserved the site of the of the period, the rivers and tea plantations the Toyohashi City Museum of Art and (1868–1912), as well as beef hot-pot and other former main plant of Toyoda Automatic Loom the trains roll past, and the dramatic History, and sports facilities. The tramway, aspects of the culinary culture of the times. The Works as part of its industrial heritage, and has mountain scenery have appeared in many which runs through the environs of the park museum grounds, one of the largest in Japan, reopened it as a commemorative museum. The TV dramas and movies. is a symbol of Toyohashi. houses more than sixty buildings from around museum, which features textile machinery and ACCESS A 5-minute walk from Toyohashikoen-mae Station on the Toyohashi Railway tramline Japan and beyond, 12 of which are designated automobiles developed by the Toyota Group, ACCESS Runs from Shin-Kanaya Station to Senzu on the Oigawa Railway ACCESS A 20-minute bus journey from as Important Cultural Properties of Japan, presents the history of industry and technology http://www.oigawa-railway.co.jp/pdf/oigawa_rail_eng.pdf Inuyama Station on the Nagoya Railroad which were dismantled and moved here. -

Wakayama Castle Selected As One of Japan's 100 Best Castles, for Its Beautiful Chalky White Castle Tower That Stands Over the Center of the City

Wakayama Castle Selected as one of Japan's 100 best castles, for its beautiful chalky white castle tower that stands over the center of the city. The castle tower also offers a spectacular view of the city. 7 min. bus ride or 20 min. walk from JR Wakayama Sta. (1.5 km) Access ・ ・5 min. bus ride or 10 min. walk from Nankai Wakayamashi Sta. (1 km) 2 3 Wakayama Castle Cherry Blossoms (late March to early April) The castle boasts some 600 cherry blossom trees that bathe the grounds in pink each spring. Fall Colors (late November to early December) See the beautiful fall colors reflected in the garden pond below, or enjoy a spot on the castle grounds surrounded entirely by brightly colored leaves. Dress-up Experience Tea Experience Try on old-fashioned outfits for feudal lords, princesses, ninjas, Enjoy green tea and Japanese sweets in the scenic Momijidani and more. Teien Garden’s teahouse. 2 3 Wakayama Marina City This resort island offers great food, hot spring baths, a theme park, and a hotel, making it a great getaway. The Tuna Cutting Show, held daily at Kuroshio Ichiba Market, is a must-see. 30 min. bus ride from JR Wakayama Sta. (9 km) Access ・ ・40 min. bus ride from Nankai Wakayamashi Sta. (10 km) 4 5 Wakayama Marina City Porto Europa A theme park with a medieval European atmosphere. Visitors can enjoy events like fireworks shows and more. Kuroshio Ichiba Market Sushi-making Experience Grab a bite to eat or do some shopping at this lively seafood marketplace. -

Access to Kinokawa City 南海本線 南 海 本 線 Wakayama-Minami Smart IC E

A BCDE Mt. Katsuragi Lookout Access to Kinokawa City Highlandハハイランドパーク粉河イラ ンParkドパ ーKokawaク粉河 8KUKVRNCEGU YKVJURKTKVWCNGPGTI[ KKishiwada-Izumiishiwada-Izumi IICC Highland Park Kokawa Campground Kaizuka Station LaLaportららぽーと Izumi和泉 Kansai International Airport Izumisano 170 Station Rinku JCT Nankai Koya Line 310 Rinku Premium Outlet 1 Osaka 480 KaminogoKaminogo IICC Rindo Kisen Kogen Line Hanwa Expressway Izumisano KKoyaguchioyaguchi Jinzu Hot Spring KKihokuihoku 4GNCZ SennanSennan JCT ICIC y KKatsuragiatsuragi swa 26 ICIC pres KKinokawa-higashiinokawa-higashi IICC a Ex JR Hanwa inaw To Nara KPVJGJQVURTKPIU JR Hanwa IICC KKeinawae Expressway Line HHannanannan IICC Line Nankai Kinokawa City Hall KKatsuragi-nishiatsuragi-nishi HHashimotoashimoto 62 127 Main Line StationStation KKinkiinki KKinokawainokawa IICC 南海本線南 UUniversityniversity 海 AAeoneon MMallall WWakayamaakayama ICIC 371 本 WakayamaWakayama JCTJCT JR Wakayama Line 線 IIwade-Negorowade-Negoro WWakayamashiakayamashi 24 ICIC KKokawaokawa SStationtation SStationtation WWakayama-kitaakayama-kita IICC UchitaUchita Gokurakubashi Ikeda Tunnel Nakatsugawa Gyojado SStationtation NNagaaga MMunicipalunicipal HHospitalospital Station Wakayama IC 424 WWakayamaakayama WWakayama-Minamiakayama-Minami SSmartmart IICC Kinokawa City Fu-no-Oka StationStation Kannonyama Fruit Garden KishiKishi StationStation mulino WWakayamaakayama ElectricElectric RRailwayailway Keinawa Expressway JR KKishigawaishigawa LLineine Sakura Pond Jutani River Kisei Line Agricultural road for broad farmland area in Kinokawa -

JRTR No.52 Public Transportation in Provincial Areas

Public Transportation in Provincial Areas New Rejuvenation Model for Regional Railways in Japan—The Case of Wakayama Electric Railway’s Kishigawa Line Katsuhisa Tsujimoto Introduction Railway Kishigawa Line between Wakayama and Kishi as the Kishigawa Line Model. This model is characterized Railways were the main passenger transport mode in Japan by broad-ranging participation by community residents, until the 1970s peak. However, with rising personal income effective support by local government, creative efforts and progress in building road networks, their market share by the new operator, and creation of a citizen–industry– was eventually overtaken by automobiles. By FY2005, the government–academia coordination system. The creation automobile’s share (passenger-km basis) of Japanese process, characteristics, and significance of these features passenger transport exceeded 50%, while that of railways had are introduced here. fallen below 30%. With the relocation of many urban functions of regional cities, such as housing, businesses, administration, Overview of Kishigawa Line education, and medical care to the suburbs, city centres, including areas near stations, have fallen into decline. The Kishigawa Line opened in February 1916 mainly to As a result, almost 70% of the 114 regional railway carry worshippers to the famous shrines at Hinokuma-jingu operators in Japan showed an operating loss in FY2005 and Kunikakasu-jingu (collectively called Nichizengu), and a total of 29 (605 km) railways, track sections and trams Kamayama-jinja, and Idakiso-jinja. Figure 1 shows the (excluding freight and funicular lines, unopened lines, and location of Wakayama and Figure 2 shows the Kishigawa Line. lines taken over by other operators) disappeared between The original line was operated by Sando Keibin Railway and 2000 and November 2008. -

Managing Public Transportation

www.internationalesverkehrswesen.de Special Edition 1 l May 2017 Volume 69 International Transportation International Transportation Managing public transportation STRATEGIES Governance – Strategies – Solutions Fit for tomorrow’s transportation challenges? BEST PRACTICE Open chances for sustainable public mobility PRODUCTS & SOLUTIONS Planning and operating with cloud assistance SCIENCE & RESEARCH Special Edition 1 | May 2017 1 | May Special Edition Intelligent mobility systems and services © Clipdealer © Hier klicken Sie richtig! IV online: Neuer Look – mehr Nutzen Informiert mit einem Klick Die Webseite von Internationales Verkehrswesen hat ein neues Das finden Sie auf www.internationalesverkehrswesen.de: Gesicht bekommen. Die aktuellen Webseiten unseres Magazins • Aktuelle Meldungen rund um Mobilität, Transport und Verkehr bringen eine frische Optik und eine Reihe neuer Funktionalitäten. • Termine und Veranstaltungen in der aktuellen Übersicht Vor allem aber: Die Webseite ist im Responsive Design gestaltet – • Übersichten, Links und Ansprechpartner für Kunden und Leser und damit auch auf Mobilgeräten wie Smartphones und Tablets • Autoren-Service mit Themen, Tipps und Formularen bestens lesbar. • Beitragsübersicht und Abonnenten-Zugang zum Heftarchiv Schauen Sie doch Trialog Publishers Verlagsgesellschaft einfach mal rein! Eberhard Buhl M.A., Dipl.-Ing. Christine Ziegler VDI Marschnerstraße 87 | 81245 München www.internationalesverkehrswesen.de +49 89 889518.71 | [email protected] Anzeige U2.indd 1 25.10.2016 10:00:42 Sebastian Belz POINT OF VIEW The organization of European railways: Confusing for the customers ocal public transportation on the streets and railways is incorporating services from many different transport providers. organized very differently around the world. Whereas This approach has been followed in Germany during the last some countries and regions have very elaborate systems 40 years, where it has increasingly become the norm. -

Area Adress Shop Name Sightseeing Accommodations Food&Drink

Area Adress Shop name Sightseeing Accommodations Food&Drink Activities Shopping Activities 392 Asahi Kuttyan-chomati Abuta-gun, Hokkaidou White Isle NISEKO ○ 145-2 Hirafu, Kutchan-cho, Abuta-gun, Hokkaido BOUKEN KAZOKU ○○○ Tanuki-koji Arcade, 5-chome, Minami-sanjo-nishi, Chuo-ku, Sapporo-shi, Hokkaido Izakaya Sakanaya Shichifukujin-Shoten Tanukikoji○ Japan Land Building 4F, 5 chome, Minami Gojo Nishi, Chuo-ku, Sapporo-shi, Hokkaido KYODORYORI NAGAI ○ 2 chome, Minami 5 jo Nishi, Abashiri-shi, Hokkaido YAKINIKU RIKI ○ 3434 kita34gou nisi9sen Kamifurano-cho, Sorachi-gun, Hokkaido WOODY LIFE ○○ 1-1-6 Hanazono, Otaru-shi, Hokkaido TATSUMI SUSHI ○ 3-5 Naruka, Toyakocho, Abuta-gun, Hokkaido SILO TENBOUDAI ○○○ 2-22 Saiwaicho, Furano-shi, Hokkaido Okonomiyaki - Senya ○ Daini Green Bldg. 1F, Minami4jonishi 3-chome, Chuo-ku, Sapporo-shi, Hokkaido(next to Susukino police booth) CHINESE RESTAURANT SAI-SAI ○ Minami6jo-dori 19-2182-103, Ashikawa-shi, Hokkaido Local Sake Storehouse - Taisetsu no Kura ○ ○ ○ 12-6 Toyokawacho, Hakodate-shi, Hokkaido LA VISTA Hakodate Bay ○ Asahidake-Onsen, Higashikawacho, Kamikawa-gun, Hokkaido La Vista Daisetsuzan ○ 4 Tanuki Koji, Nishi-4Chome, Minami-3jo, Chuoku, Sapporo-shi, Hokkaido BIG SOUVENIR SHOP TANUKIYA ○ Hotel Parkhills,Shiroganeonsen,Biei-cho,Kamikawa-gun,Hokkaido HOTEL PARKHILLS ○ ○ ○ 1-1 Otemachi, Hakodate-shi, Hokkaido Hotel Chocolat Hakodate ○ Shiroganeonsen,Biei-cho,Kamikawa-gun,Hokkaido SHIROGANE ONSEN HOTSPRING ○ ○ ○ 142-5, Toyako Onsen, Toyako-cho, Abuta-gun, Hokkaido TOYAKO VISITOR CENTE/VOLCANO SCIENCE -

Heisei No Ryujin Kaido Paper Making at This Studio

“The Road to Beauty” YASUDA-GAMI Warashi 体験交流工房わらし The studio of Wakayama’s traditional Washi TEL: 0737-25-0621 paper called “Yasuda-gami”. You can experience Address: Wakayama Prefecture, Arida-gun, Aridagawa-cho, Shimizu1218-1 Heisei no Ryujin Kaido paper making at this studio. The ingredients of 和歌山県有田郡有田川清水1218-1 Washi paper contain vitamin B, which will Hours: 8:30a.m.-5:00p.m.(workshop 9:00a.m.-3:00p.m.) make your hands nice and smooth! Closed on Wednesdays, Thursdays, Holidays, 1/1-3, 8/14-15 Parking: Available “The Road to Beauty” WOOD FURNITURE G. WORKS TEL: 0739-77-0785 The handcrafted furniture shop and gallery. Address: Wakayama Prefecture, Tanabe city, Ryujinmura, Fukui493 This shop is full of freshly produced furniture made 和歌山県田辺市龍神村福井493 from locally grown trees and beautiful art works Hours: 10:00a.m.-5:00p.m. by local artists. The aroma of Japanese cedar helps Closed on Wednesdays you relax and leads to a good sleep! (unless Wednesday falls on a holiday, in which case closed Thursday) Parking: Available “The Road to Beauty” TOFU Café Tokugawa Yorinobu, the 10th son of Tokugawa Ieyasu, was the feudal lord of the Ryujin Tofu Café Loin るあん TEL: 0739-79-0637 Address: Wakayama Prefecture, Tanabe city, House of Kishu (present day Wakayama Prefecture) in the early Edo period. Everybody knows Tofu is a staple of “beauty food”. Ryujinmura, Komatagawa 259 Loin’s Tofu is made over a wood fire in the traditional 和歌山県田辺市龍神村小又川259 He was good at studies and also an Onsen lover. Ryujin custom. The fresh air and clean water of Tofu shop: 9:00a.m. -

WAKAYAMA CITY TOURISM GUIDE If You Here a Trip Planned to Japan

WAKAYAMA CITY TOURISM GUIDE If you here a trip planned to Japan. you ought to come to Wakayama. a . m a y a k a W t e r c e s y m Wakayama Castle Cherry Blossoms (late March to early April) The castle boasts some 600 cherry blossom trees that bathe the grounds in pink each spring. Fall Colors (late November to early December) See the beautiful fall colors reflected in the garden pond below, or enjoy a spot on the castle grounds surrounded entirely by brightly colored leaves. Wakayama Castle Selected as one of Japan's 100 best castles, for its beautiful chalky white castle tower that stands over the center of the city. The castle tower also offers a spectacular view of the city. 7 min. bus ride or 20 min. walk from JR Wakayama Sta. (1.5 km) Access ・ Dress-up Experience Tea Experience ・5 min. bus ride or 10 min. walk from Nankai Wakayamashi Sta. (1 km) Try on old-fashioned outfits for feudal lords, princesses, ninjas, Enjoy green tea and Japanese sweets in the scenic Momijidani and more. Teien Garden’s teahouse. 2 3 Wakayama Marina City Porto Europa A theme park with a medieval European atmosphere. Visitors can enjoy events like fireworks shows and more. Kuroshio Ichiba Market Sushi-making Experience Grab a bite to eat or do some shopping at this lively seafood marketplace. Learn how to make authentic nigiri sushi from a professional Visitors can even buy fresh seafood at the shops and grill it at a restaurant here. sushi chef. -

Kinokawa City Tour Map Attached

We will provide up-to-the-minute tourist information for Kinokawa City. Kinokawa City Tour Map attached. Kinokawa City Tourist Information Center has opened! With ease Stay healthy in body and mind Luxurious and rich smile Year-round fruit experiences Visit the Kinokawa City homepage for more information! ▶ 2 Osaka Prefecture Kinokawa City Tour Map Katsuragi-san Observation Deck ● Highland Park Kokawa● KINOKAWA CITY MAP 0 1km 2km 3km Highland Park Kokawa Campsite In Kinokawa City, people are able to get among fruit and nature. Use the Kinokawa City Tour From Kaminogou IC Map to discover the recommended spots to visit. ↓ Jinzu Onsen Hot Spring 62 127 Osaka Ikeda Tunnel Wakayama Fuu-no-Oka Kinokawa City 125 Kasuga-jinja Jyutani-gawa River Shrine Keinawa Expressway Sakura-ike Pond 121 Seishu-no-Sato 127 Michi-no-Eki Kinokawa-higashi IC ⑭ Roadside Rest Area Kinki University Kinokawa IC ● Kaito-ike Pond Bioengineering ● Department Kai-jinja ⑮ Shrine Kokawa Ubusuna-jinja Shrine 122 Tatsu-no-Toi Jyuzen-ritsuin ● ● Temple Pressed ⑦ flower ● Nishi-Kaseda Station Iwade City ⑪ Mekkemon Plaza 7 Kokawa-dera Temple classroom 宿 Maruasa Ryokan ● ● Nate Hachiman-jinja 7 ● Akiba-san Park Former ● Shrine ⑨ Tourist Specialties Center Kokawa Nate-jyuku 119 Nagata Shiki Group From Sennan IC ⑧ Honjin Katsuragi Legend ⑩ Kannon Kokawa ● HAJIME-café Oozu-ohashi ↓ 131 Temple Station Bridge Pine tree of Yakushi-ji Temple Nate Station Town 宿 Business Hotel Kinokawa City Boundary of city, Former Kii ● Kokawa town and village ● Kokubun-ji Temple Site Naga Branch Office -

National Regional Traffic Activation Case Studies

Policy Material 220102 The Nippon Foundation Grant Project National Regional Traffic Activation Case Studies March 2011 Institution for Transport Policy Studies Introduction This collection of case studies is a summary of detailed cases (micro data) obtained from interviews in municipalities as part of the “Information Gathering and the Provision of Web Information for the Activation of Regional Transportation” project with the support of the Nippon Foundation over the three years of FY2008- 2010. As the state of regional public transport becomes more and more difficult each year, and given the pressing need for local governments to revitalize and rehabilitate their regional public transportation systems, the “Revitalization and Rehabilitation of Local Public Transportation Systems Act” was implemented in October 2007. This law seeks that municipalities that are at the forefront of this issue take on the role of “regional public transport producers”, examining the transportation needs of their regions, reviewing public transport from the perspective of its users, and playing a central role in the formulation of regional public transport plans. Also, in the municipality survey conducted over the last three years by the Public Transport Support Center (“Questionnaire on the Provision of Information by the Public Transport Support Center”), it was clear that local government personnel in each region had a high need for information on “trends in other local governments” and “case studies of implemented measures”. This collection of cases studies is a collection of various measures related to public transport from Japan and overseas, to provide information on the revitalization and rehabilitation of regional public transport systems, for municipalities and other related stakeholders such as public transport users, residents, commercial facilities and businesses, hospitals and schools etc., in response to the roles and information needs of local government officials.