Agency in Fanfiction Jargon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fan Cultures Pdf, Epub, Ebook

FAN CULTURES PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Matthew Hills | 256 pages | 01 Mar 2002 | Taylor & Francis Ltd | 9780415240253 | English | London, United Kingdom Fan Cultures PDF Book In America, the fandom also began as an offshoot of science fiction fandom, with fans bringing imported copies of Japanese manga to conventions. Rather than submitting a work of fan fiction to a zine where, if accepted, it would be photocopied along with other works and sent out to a mailing list, modern fans can post their works online. Those who fall victim to the irrational appeals are manipulated by mass media to essentially display irrational loyalties to an aspect of pop culture. Harris, Cheryl, and Alison Alexander. She addresses her interests in American cultural and social thought through her works. In doing so, they create spaces where they can critique prescriptive ideas of gender, sexuality, and other norms promoted in part by the media industry. Stanfill, Mel. Cresskill, N. In his first book Fan Cultures , Hills outlines a number of contradictions inherent in fan communities such as the necessity for and resistance towards consumerism, the complicated factors associated with hierarchy, and the search for authenticity among several different types of fandom. Therefore, fans must perpetually occupy a space in which they carve out their own unique identity, separate from conventional consumerism but also bolster their credibility with particular collectors items. They rose to stardom separately on their own merits -- Pickford with her beauty, tumbling curls, and winning combination of feisty determination and girlish sweetness, and Fairbanks with his glowing optimism and athletic stunts. Gifs or gif sets can be used to create non-canon scenarios mixing actual content or adding in related content. -

For Fans by Fans: Early Science Fiction Fandom and the Fanzines

FOR FANS BY FANS: EARLY SCIENCE FICTION FANDOM AND THE FANZINES by Rachel Anne Johnson B.A., The University of West Florida, 2012 B.A., Auburn University, 2009 A thesis submitted to the Department of English and World Languages College of Arts, Social Sciences, and Humanities The University of West Florida In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts 2015 © 2015 Rachel Anne Johnson The thesis of Rachel Anne Johnson is approved: ____________________________________________ _________________ David M. Baulch, Ph.D., Committee Member Date ____________________________________________ _________________ David M. Earle, Ph.D., Committee Chair Date Accepted for the Department/Division: ____________________________________________ _________________ Gregory Tomso, Ph.D., Chair Date Accepted for the University: ____________________________________________ _________________ Richard S. Podemski, Ph.D., Dean, Graduate School Date ACKNOWLEDGMENTS First, I would like to thank Dr. David Earle for all of his help and guidance during this process. Without his feedback on countless revisions, this thesis would never have been possible. I would also like to thank Dr. David Baulch for his revisions and suggestions. His support helped keep the overwhelming process in perspective. Without the support of my family, I would never have been able to return to school. I thank you all for your unwavering assistance. Thank you for putting up with the stressful weeks when working near deadlines and thank you for understanding when delays -

A Portrait of Fandom Women in The

DAUGHTERS OF THE DIGITAL: A PORTRAIT OF FANDOM WOMEN IN THE CONTEMPORARY INTERNET AGE ____________________________________ A Thesis Presented to The Honors TutoriAl College Ohio University _______________________________________ In PArtiAl Fulfillment of the Requirements for Graduation from the Honors TutoriAl College with the degree of Bachelor of Science in Journalism ______________________________________ by DelAney P. Murray April 2020 Murray 1 This thesis has been approved by The Honors TutoriAl College and the Department of Journalism __________________________ Dr. Eve Ng, AssociAte Professor, MediA Arts & Studies and Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Thesis Adviser ___________________________ Dr. Bernhard Debatin Director of Studies, Journalism ___________________________ Dr. Donal Skinner DeAn, Honors TutoriAl College ___________________________ Murray 2 Abstract MediA fandom — defined here by the curation of fiction, art, “zines” (independently printed mAgazines) and other forms of mediA creAted by fans of various pop culture franchises — is a rich subculture mAinly led by women and other mArginalized groups that has attracted mAinstreAm mediA attention in the past decAde. However, journalistic coverage of mediA fandom cAn be misinformed and include condescending framing. In order to remedy negatively biAsed framing seen in journalistic reporting on fandom, I wrote my own long form feAture showing the modern stAte of FAndom based on the generation of lAte millenniAl women who engaged in fandom between the eArly age of the Internet and today. This piece is mAinly focused on the modern experiences of women in fandom spaces and how they balAnce a lifelong connection to fandom, professional and personal connections, and ongoing issues they experience within fandom. My study is also contextualized by my studies in the contemporary history of mediA fan culture in the Internet age, beginning in the 1990’s And to the present day. -

Black Panther Toolkit! We Are Excited to Have You Here with Us to Talk About the Wonderful World of Wakanda

1 Fandom Forward is a project of the Harry Potter Alliance. Founded in 2005, the Harry Potter Alliance is an international non-profit that turns fans into heroes by making activism accessible through the power of story. This toolkit provides resources for fans of Black Panther to think more deeply about the social issues represented in the story and take action in our own world. Contact us: thehpalliance.org/fandomforward [email protected] #FandomForward This toolkit was co-produced by the Harry Potter Alliance, Define American, and UndocuBlack. @thehpalliance @defineamerican @undocublack Contents Introduction................................................................................. 4 Facilitator Tips............................................................................. 5 Representation.............................................................................. 7 Racial Justice.............................................................................. 12 » Talk It Out.......................................................................... 17 » Take Action............................................................................ 18 Colonialism................................................................................... 19 » Talk It Out.......................................................................... 23 » Take Action............................................................................24 Immigrant Justice........................................................................25 » -

Universidade Federal De Goiás Faculdade De Informação E Comunicação Graduação Em Publicidade E Propaganda

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DE GOIÁS FACULDADE DE INFORMAÇÃO E COMUNICAÇÃO GRADUAÇÃO EM PUBLICIDADE E PROPAGANDA NATÁLIA SANTOS DIAS ANÁLISE NARRATIVA E INTELIGÊNCIA COLETIVA: UM ESTUDO DAS PRÁTICAS DA WIKI TV TROPES GOIÂNIA 2018 NATÁLIA SANTOS DIAS ANÁLISE NARRATIVA E INTELIGÊNCIA COLETIVA: UM ESTUDO DAS PRÁTICAS DA WIKI TV TROPES Trabalho apresentado à Banca Examinadora do Curso de Comunicação Social - Publicidade e Propaganda, da Faculdade de Informação e Comunicação da Universidade Federal de Goiás, como exigência parcial para a Conclusão de Curso. Orientação: Prof. Dr. Rodrigo Cássio Oliveira GOIÂNIA 2018 NATÁLIA SANTOS DIAS ANÁLISE NARRATIVA E INTELIGÊNCIA COLETIVA: UM ESTUDO DAS PRÁTICAS DA WIKI TV TROPES Monografia defendida no curso de Bacharelado em Comunicação Social - Publicidade e Propaganda da Faculdade de Informação e Comunicação da Universidade Federal de Goiás, para a obtenção do grau de Bacharel, defendida e aprovada em 26/11/2018, pela Banca Examinadora constituída pelos seguintes professores: ______________________________________________________ Prof. Dr. Rodrigo Cássio Oliveira (UFG) Presidente da Banca ______________________________________________________ Prof. Drª. Lara Lima Satler (UFG) Membro da Banca ______________________________________________________ Prof. Dr. Cleomar de Sousa Rocha (UFG) Membro da Banca AGRADECIMENTOS Agradeço aos meus pais Cleoneide Dias e Júlio Cézar, pelo incentivo, o apoio e por me ensinarem desde cedo a amar as histórias; À Rodrigo Cássio Oliveira, orientador e professor exemplar, por me -

Fanfiction and Imaginative Reading a Dissertation

"I Opened a Book and in I Strode": Fanfiction and Imaginative Reading A dissertation presented to the faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy Ashley J. Barner April 2016 © 2016 Ashley J. Barner. All Rights Reserved. 2 This dissertation titled "I Opened a Book and in I Strode": Fanfiction and Imaginative Reading by ASHLEY J. BARNER has been approved for the Department of English and the College of Arts and Sciences by Robert Miklitsch Professor of English Robert Frank Dean, College of Arts and Sciences 3 ABSTRACT BARNER, ASHLEY J., Ph.D., April 2016, English "I Opened a Book and in I Strode": Fanfiction and Imaginative Reading Director of Dissertation: Robert Miklitsch This dissertation studies imaginative reading and its relationship to fanfiction. Imaginative reading is a practice that involves engaging the imagination while reading, mentally constructing a picture of the characters and settings described in the text. Readers may imaginatively watch and listen to the narrated action, using imagination to recreate the characters’ sensations and emotions. To those who frequently read this way, imagining readers, the text can become, through the work of imagination, a play or film visualized or entered. The readers find themselves inside the world of the text, as if transported to foreign lands and foreign eras, as if they have been many different people, embodied in many different fictional characters. By engaging imaginatively and emotionally with the text, the readers can enter into the fictional world: the settings seem to them like locations they can visit, the many characters like roles they can inhabit or like real people with whom they can interact as imaginary friends and lovers. -

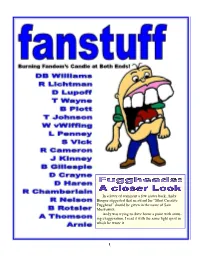

Fanstuff 41 It Got Me Thinking About Sam and Then the General Topic of Fuggheads and Fuggheadedness

In a letter of comment a few issues back, Andy Hooper suggested that an award for “Most Creative Fugghead” should be given in the name of Sam Moskowitz. Andy was trying to drive home a point with amus- ing exaggeration. I read it with the same light spirit in which he wrote it. 1 Yet Truth often lurks beneath a thin veneer of humor. Andy’s quip raised some intriguing questions. Fanstuff 41 It got me thinking about SaM and then the general topic of fuggheads and fuggheadedness. (I’ll get to Sam Moskowitz later in this issue.) “Fugghead” ranks as the most incendiary fanspeak insult. If you want to make a new enemy in Fandom, smacking them with “fugghead” is a Bill of Fare fine start. It’s a strange word, too. Almost every fan knows what “fugghead” means and most can cite examples of the breed in all its infinite variety. The only hitch is that each Cover Essay fan’s list of fuggheads is a little different from all of the others. Fuggheads: Yet no one has proposed a comprehensive, accurate definition. A Closer Look Lack of an objective standard makes it a highly subjective judgment. Arnie/1 One fan’s “fugghead” is another’s BNF. A fan once described a fugghead as “someone who never has second thoughts.” That’s clever, and true as far as it goes, but it’s incomplete. Who Gets An Exemption? It isn’t that simple. Hasty, visceral responses are more likely to veer Arnie/2 Fen Den Who Gets a Free Pass? SaM & Me: Trufans, in general, aren’t rules-worshipping bureaucrats. -

The JACK KIRBY COLLECTOR #69

1 82658 00098 1 The JACK KIRBY COLLECTOR FALL 2016 FALL $10.95 #69 All characters TM & © Simon & Kirby Estates. THE Contents PARTNERS! OPENING SHOT . .2 (watch the company you keep) FOUNDATIONS . .3 (Mr. Scarlet, frankly) ISSUE #69, FALL 2016 C o l l e c t o r START-UPS . .10 (who was Jack’s first partner?) 2016 EISNER AWARDS NOMINEE: BEST COMICS-RELATED PERIODICAL PROSPEAK . .12 (Steve Sherman, Mike Royer, Joe Sinnott, & Lisa Kirby discuss Jack) KIRBY KINETICS . .18 (Kirby + Wood = Evolution) FANSPEAK . .22 (a select group of Kirby fans parse the Marvel settlement) JACK KIRBY MUSEUM PAGE . .29 (visit & join www.kirbymuseum.org) KIRBY OBSCURA . .30 (Kirby sees all!) CLASSICS . .32 (a Timely pair of editors are interviewed) RE-PAIRINGS . .36 (Marvel-ous cover recreations) GALLERY . .39 (some Kirby odd couplings) INPRINT . .49 (packaging Jack) INNERVIEW . .52 (Jack & Roz—partners for life) INCIDENTAL ICONOGRAPHY . .60 (Sandman & Sandy revamped) OPTIKS . .62 (Jack in 3-D Land) SCULPTED . .72 (the Glenn Kolleda incident) JACK F.A.Q.s . .74 (Mark Evanier moderates the 2016 Comic-Con Tribute Panel, with Kevin Eastman, Ray Wyman Jr., Scott Dunbier, and Paul Levine) COLLECTOR COMMENTS . .92 (as a former jazz bass player, the editor of this mag was blown away by the Sonny Rollins letter...) PARTING SHOT . .94 (never trust a dwarf with a cannon) Cover inks: JOE SINNOTT from Kirby Unleashed Cover color: TOM ZIUKO If you’re viewing a Digital Edition of this publication, PLEASE READ THIS: This is copyrighted material, NOT intended Direct from Roz Kirby’s sketchbook, here’s a team of partners that holds a for downloading anywhere except our website or Apps. -

Making Visible

Timo Arnall Making Visible Mediating the material of emerging technology PhD thesis 66 © Timo Arnall, 2013 ISSN 1502-217x ISBN 978-82-547-0262-8 CON-TEXT 66 Making Visible Akademisk doktorgradsavhandling avgitt ved Arkitekthøgskolen i Oslo UTGIVER: Arkitektur- og designhøgskolen i Oslo BILDE OMSLAG: Timo Arnall TRYKK: Navn på trykkeri DESIGN AV BASISMAL: BMR III Contents Acknowledgements 1 Abstract 3 Chapter 1 Discovering mediational material 5 The visible and invisible landscape of interfaces 6 Overview, focus and questions 10 Making invisible materials visible 12 The mediational, material and communicative 16 Key concepts 17 Design mediation 17 Design material 18 Discursive design and communication 19 Design research approach and methods 20 Unpacking the three approaches 22 Approach 1: Engaging with rfid as a technocultural phenomena 22 Approach 2: Exploring rfid as a design material 27 Approach 3: Mediation and communication of rfid 33 The type, outline and summary of this thesis 37 Type 37 Outline and summary 37 Research questions addressed in the articles 38 Summary 39 Chapter 2 Background and Contexts 40 Designing technoculture 41 Rfid: technical, cultural and historical perspectives 45 A brief history of rfid 45 Promises and controversy 48 Popular imaginations and folk-theories 51 Towards a mundane reality 52 The disappearing interface 53 The concept of seamlessness 57 Mediation and remediation of interface technology 60 Defining digital design materials 64 Material exploration 67 Visual communication 71 Semiotics in design 71 Visualisation -

Today Your Barista Is: Genre Characteristics in the Coffee Shop Alternate Universe

Today Your Barista Is: Genre Characteristics in The Coffee Shop Alternate Universe Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Katharine Elizabeth McCain Graduate Program in English The Ohio State University 2020 Dissertation Committee Sean O’Sullivan, Advisor Matthew H. Birkhold Jared Gardner Elizabeth Hewitt 1 Copyright by Katharine Elizabeth McCain 2020 2 Abstract This dissertation, Today Your Barista Is: Genre Characteristics in The Coffee Shop Alternate Universe, works to categorize and introduce a heretofore unrecognized genre within the medium of fanfiction: The Coffee Shop Alternate Universe (AU). Building on previous sociological and ethnographic work within Fan Studies, scholarship that identifies fans as transformative creators who use fanfiction as a means of promoting progressive viewpoints, this dissertation argues that the Coffee Shop AU continues these efforts within a defined set of characteristics, merging the goals of fanfiction as a medium with the specific goals of a genre. These characteristics include the Coffee Shop AU’s structure, setting, archetypes, allegories, and the remediation of related mainstream genres, particularly the romantic comedy. The purpose of defining the Coffee Shop AU as its own genre is to help situate fanfiction within mainstream literature conventions—in as much as that’s possible—and laying the foundation for future close reading. This work also helps to demonstrate which characteristics are a part of a communally developed genre as opposed to individual works, which may assist in legal proceedings moving forward. However, more crucially this dissertation serves to encourage the continued, formal study of fanfiction as a literary and cultural phenomenon, one that is beginning to closely analyze the stories fans produce alongside the fans themselves. -

Women and Yaoi Fan Creative Work เพศหญิงและงานสร้างสรรค์แนวยาโอย

Women and Yaoi Fan Creative Work เพศหญิงและงานสร้างสรรค์แนวยาโอย Proud Arunrangsiwed1 พราว อรุณรังสีเวช Nititorn Ounpipat2 นิติธร อุ้นพิพัฒน์ Krisana Cheachainart3 Article History กฤษณะ เชื้อชัยนาท Received: May 12, 2018 Revised: November 26, 2018 Accepted: November 27, 2018 Abstract Slash and Yaoi are types of creative works with homosexual relationship between male characters. Most of their audiences are female. Using textual analysis, this paper aims to identify the reasons that these female media consumers and female fan creators are attracted to Slash and Yaoi. The first author, as a prior Slash fan creator, also provides part of experiences to describe the themes found in existing fan studies. Five themes, both to confirm and to describe this phenomenon are (1) pleasure of same-sex relationship exposure, (2) homosexual marketing, (3) the erotic fantasy, (4) gender discrimination in primacy text, and (5) the need of equality in romantic relationship. This could be concluded that these female fans temporarily identify with a male character to have erotic interaction with another male one in Slash narrative. A reason that female fans need to imagine themselves as a male character, not a female one, is that lack of mainstream media consists of female characters with a leading role, besides the romance genre. However, the need of gender equality, as the reason of female fans who consume Slash text, might be the belief of fan scholars that could be applied in only some contexts. Keywords: Slash, Yaoi, Fan Creation, Gender 1Faculty of -

Spirits of Things Past Is Published by Dick Smith ([email protected]) and Edited by Leah Zeldes Smith ([email protected]), 410 W

No. 1 April 2001 A fanzine of progress for & F H C 11 anzines and fan history? Of course. The 14th edition of ditto, the friendly fanzine fans’ convention, will F be held in October 2001 at the Tucker Hotel in Bloomington, Ill. This year, ditto will be combined with FanHistoriCon for a weekend of festivities fêting fine fannish traditions. We invite you to join us for discussions of fanzines, fannish history, fandom in general and the best ways to preserve them. Bring us your best zines, your tall tales, your favorite fanecdotes. Bring us your questions about fandom’s past and your concerns about its future. Do good. Avoid evil. Pub your ish. Spirits of Things Past is published by Dick Smith ([email protected]) and edited by Leah Zeldes Smith ([email protected]), 410 W. Willow Road, Prospect Heights, IL 60070-1250, +1 (847) 394-1950. II ditto 14 1 SPIRITS OF THINGS PAST Who? Your hosts — Dick Smith, Leah Zeldes Smith, Wilson “Bob” Tucker, Fern Tucker, Henry Welch and Letha Welch. Attending members (so far) — Bill Bowers, Linda Bushyager, Catherine Crockett, Carolyn Doyle, George Flynn, Teddy Harvia, Colin Hinz, Valli Hoski, Cris Kaden, Neil Kaden, Mary Kay Kare, Hope Leibowitz, Eric Lindsay, Sam Long, Murray Moore, Mark Olson, Priscilla Olson, Dave Rowe, Pat Sims, Roger Sims, Dick Spelman, Keith Stokes, Diana Thayer, Pat Virzi, Bob Webber, Toni Weisskopf, Art Widner … and you, we hope. (Supporting members — Harry Andrushak, Moshe Feder, Catherine Mintz, Bobb Waller and Michael Waite.) What? A weekend celebrating science-fiction fandom, fanzines and fanhistory.