Hybridizing Collard and Cabbage May Provide a Means to Develop

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vegetables: Dark-Green Leafy, Deep Yellow, Dry Beans and Peas (Legumes), Starchy Vegetables and Other Vegetables1 Glenda L

Archival copy: for current recommendations see http://edis.ifas.ufl.edu or your local extension office. FCS 1055 Vegetables: Dark-Green Leafy, Deep Yellow, Dry Beans and Peas (legumes), Starchy Vegetables and Other Vegetables1 Glenda L. Warren2 • Deep yellow vegetables provide: Vitamin A. Eat 3 to 5 servings of vegetables each day. Examples: Carrots, pumpkins, sweet potatoes, Include all types of vegetables regularly. winter squash. What counts as one serving? • 1 cup of raw leafy vegetables (such as lettuce or spinach) • ½ cup of chopped raw vegetables • ½ cup of cooked vegetables • ¾ cup of vegetable juice Eat a variety of vegetables • Dry Beans and Peas (legumes) provide: It is important to eat many different vegetables. Thiamin, folic acid, iron, magnesium, All vegetables provide dietary fiber, some provide phosphorus, zinc, potassium, protein, starch, starch and protein, and they are also sources of fiber. Beans and peas can be used as meat many vitamins and minerals. alternatives since they are a source of protein. Examples: Black beans, black-eyed peas, • Dark-green vegetables provide: Vitamins A chickpeas (garbanzos), kidney beans, lentils, and C, riboflavin, folic acid, iron, calcium, lima beans (mature), mung beans, navy beans, magnesium, potassium. Examples: Beet pinto beans, split peas. greens, broccoli, collard greens, endive, • Starchy vegetables provide: Starch and escarole, kale, mustard greens, romaine varying amounts of certain vitamins and lettuce, spinach, turnip greens, watercress. minerals, such as niacin, vitamin B6, zinc, and 1. This document is FCS 1055, one of a series of the Department of Family, Youth and Community Sciences, Florida Cooperative Extension Service, Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences, University of Florida. -

Companion Plants for Better Yields

Companion Plants for Better Yields PLANT COMPATIBLE INCOMPATIBLE Angelica Dill Anise Coriander Carrot Black Walnut Tree, Apple Hawthorn Basil, Carrot, Parsley, Asparagus Tomato Azalea Black Walnut Tree Barberry Rye Barley Lettuce Beans, Broccoli, Brussels Sprouts, Cabbage, Basil Cauliflower, Collard, Kale, Rue Marigold, Pepper, Tomato Borage, Broccoli, Cabbage, Carrot, Celery, Chinese Cabbage, Corn, Collard, Cucumber, Eggplant, Irish Potato, Beet, Chive, Garlic, Onion, Beans, Bush Larkspur, Lettuce, Pepper Marigold, Mint, Pea, Radish, Rosemary, Savory, Strawberry, Sunflower, Tansy Basil, Borage, Broccoli, Carrot, Chinese Cabbage, Corn, Collard, Cucumber, Eggplant, Beet, Garlic, Onion, Beans, Pole Lettuce, Marigold, Mint, Kohlrabi Pea, Radish, Rosemary, Savory, Strawberry, Sunflower, Tansy Bush Beans, Cabbage, Beets Delphinium, Onion, Pole Beans Larkspur, Lettuce, Sage PLANT COMPATIBLE INCOMPATIBLE Beans, Squash, Borage Strawberry, Tomato Blackberry Tansy Basil, Beans, Cucumber, Dill, Garlic, Hyssop, Lettuce, Marigold, Mint, Broccoli Nasturtium, Onion, Grapes, Lettuce, Rue Potato, Radish, Rosemary, Sage, Thyme, Tomato Basil, Beans, Dill, Garlic, Hyssop, Lettuce, Mint, Brussels Sprouts Grapes, Rue Onion, Rosemary, Sage, Thyme Basil, Beets, Bush Beans, Chamomile, Celery, Chard, Dill, Garlic, Grapes, Hyssop, Larkspur, Lettuce, Cabbage Grapes, Rue Marigold, Mint, Nasturtium, Onion, Rosemary, Rue, Sage, Southernwood, Spinach, Thyme, Tomato Plant throughout garden Caraway Carrot, Dill to loosen soil Beans, Chive, Delphinium, Pea, Larkspur, Lettuce, -

Shrimpy Macaroni Salad Fries, Smoked Oyster Mayo Brussels

FIRST THINGS FIRST / 9 génépy, kina, gin, club soda PEEL’N’EAT SHRIMP (boiled when you order!) ....... 16.95 WHITE SOTX traditional or Thai basil-garlic butter SALTY / La Guita Manzanilla Sherry (3oz) .......... 5/40 WHY NOT? / 14 WOOD ROASTED GULF OYSTERS ..................... 16.95/32.95 RACY / Tyrrell’s Hunter Valley Semillon 2016 ....... 55 champagne, sugar cube, bitters, grapefruit essence smoked jalapeño or parmesan garlic CLEAN / Chateau de la Ragotiere Muscadet 2017 ... 9/36 ALL NIGHT / 10 TX BLUE CRAB FINGERS ...................................... 14.95 sherry, vermouth blanc, mezcal, dry curaçao seasonal and messy!! Thai basil-garlic butter MINERAL / Gerard Morin ‘VV’ Sancerre 2016 ............ 64 CLASSIC / Louis Michel ‘Forêts’ Chablis 1er 2014 .... 88 DAD’S DAIQUIRI / 13 rhum, lime, royal combier, fernet, cracked pepper RICH / Sandhi ‘Sta. Barbara’ Chardonnay 2015 .... 13/52 ANALOG / 12 VIBRANT / Envínate ‘Palo Blanco’ Tenerife 2016 ..... 79 FRUITY / Von Hövel Riesling Kabinett 2016 ........12/48 mezcal, vermouth rosso, two aperitivos FRIED CHICKEN 18.95 / 35.95 YOU’RE WELCOME / 13 half or whole bird served with bourbon & rye, two vermouths, bitters biscuits and pickles & choice of: PINK green harissa, honey sambal, LIGHT PINK / Cortijo Rosado de Rioja 2017 ......... 10/40 oyster mayonnaise MED. PINK / Matthiasson California Rosé 2017 ....... 56 Add a ½ lb fried gulf shrimp ... 16.95 DEEP PINK / Bisson Ciliegiolo Rosato 2016 ............. 59 Bisol ‘Jeio’ Prosecco Superiore ............................. 35 RED Stéphane Tissot Crémant de Jura ...................... 14/56 PLAYFUL / Dupeuble Beaujolais 2017 .................. 11/44 ELEGANT / Anthill Farms Pinot Noir 2015 .............. 86 Larmandier-Bernier ‘Latitude’ Champagne ............ 83 HOUSE BAKED YEAST ROLLS ................................... 4.95 butter, maldon CHARMING / Turley Cinsault 2017 ........................... 63 R. -

Asparagus Broccolette Collard Greens Lacinato Kale Bok Choy Cilantro

ORGANIC ORGANIC Asparagus Bok Choy • Should be healthy green color, though a little • Cruciferous vegetable, also known purpling is fine; avoid wrinkled spears, or soft tips as Chinese cabbage • Wrap moist paper towel around stems and store in • All parts are edible; mild with somewhat sweet taste refrigerator; highly perishable • Nutrient rich – 21 different nutrients • Cut or snap tougher bottom portion of • Low calorie, low glycemic levels, has spear off – usually last 3/4˝ to 1-1/2˝ anti-inflammatory benefits DELIVERED FROM DELIVERED FROM • Steam, blanch, grill, roast, saute or THE FARM BY • Store whole head in plastic bag THE FARM BY microwave; only cook to al dente texture in refrigerator crisper ORGANIC ORGANIC Broccolette Cilantro • Strong, fresh flavor and aroma – • A cross between Chinese kale and broccoli like an intense version of parsley • Delicate and sweet broccoli flavor with hint • Wash, discard roots, store in refrigerator in of asparagus zip pouch or wrapped in slightly damp paper towel • Dark green; should not be limp or flabby • Also known as coriander • Deep-green leaves possess antioxidants, Do not overcook essential oils, vitamins, and dietary fiber • DELIVERED FROM DELIVERED FROM THE FARM BY • Stems can be chopped and utilized THE FARM BY as well as leaves ORGANIC ORGANIC Collard Greens Fennel • Very mild, almost smoky flavor; • AKA Anise; texture of celery without smaller size leaves are more tender stringiness, mild licorice flavor • High fiber, low calorie and low glycemic • Entire plant is edible, though white -

VEGGIE of the MONTH - Collards & Kale NC Cooperative Extension - Cleveland County Center December, 2014

VEGGIE OF THE MONTH - Collards & Kale NC Cooperative Extension - Cleveland County Center December, 2014 If you are looking for Greens have been cooked/used for thousands of ways to eat more years. Collards, kale and many other leafy greens nutritiously, adding leafy are available year round. However they are cool sea- greens to your diet is a son crops and are best in spring and fall. Look for a great way to accomplish variety of greens at local this goal. The word farmers markets, vegetable “greens” is commonly used to describe a variety of stands and grocery stores leafy green vegetables including collards, kale, during December. spinach, mustard & turnip greens, as well as dark salad greens such as romaine & leaf lettuce. Selection Tips • All greens are best Nutrition Benefits: when dark green, Collards and kale are packed with nutrients and young, tender & fresh. have many health benefits. Greens are an excellent Smaller leaves and source of: bunches will be more Vitamin A (important for healthy skin & eyes) tender. Vitamin C (helps resist infections & heals Avoid leaves that are wounds) yellowed, wilted, or that Folate, (a B-vitamin important to new cell have insect damage. production & maintenance, key for women of Remember greens child-bearing age) ‘cook-down’ approximately one-quarter or more Minerals: iron, calcium; other nutrients: from their original volume; purchase antioxidants & phytochemicals accordingly – 1 pound raw kale yields about 2 Dietary fiber cups cooked kale. Leafy greens can help maintain a strong immune Storage Tips system, reduce the risk of some types of cancer, and Wrap un-washed greens in damp paper towels and other chronic diseases, i.e. -

Recipe List by Page Number

1 Recipes by Page Number Arugula and Herb Pesto, 3 Lemon-Pepper Arugula Pizza with White Bean Basil Sauce, 4 Shangri-La Soup, 5 Summer Arugula Salad with Lemon Tahini Dressing, 6 Bok Choy Ginger Dizzle, 7 Sesame Bok Choy Shiitake Stir Fry, 7 Bok Choy, Green Garlic and Greens with Sweet Ginger Sauce, 8 Yam Boats with Chickpeas, Bok Choy and Cashew Dill Sauce, 9 Baked Broccoli Burgers, 10 Creamy Dreamy Broccoli Soup, 11 Fennel with Broccoli, Zucchini and Peppers, 12 Romanesco Broccoli Sauce, 13 Stir-Fry Toppings, 14 Thai-Inspired Broccoli Slaw, 15 Zesty Broccoli Rabe with Chickpeas and Pasta, 16 Cream of Brussels Sprouts Soup with Vegan Cream Sauce, 17 Brussels Sprouts — The Vegetable We Love to Say We Hate, 18 Roasted Turmeric Brussels Sprouts with Hemp Seeds on Arugula, 19 Braised Green Cabbage, 20 Cabbage and Red Apple Slaw, 21 Cabbage Lime Salad with Dijon-Lime Dressing, 22 Really Reubenesque Revisited Pizza, 23 Simple Sauerkraut, 26 Chipotle Cauliflower Mashers, 27 Raw Cauliflower Tabbouleh, 28 Roasted Cauliflower and Chickpea Curry, 29 Roasted Cauliflower with Arugula Pesto, 31 Collard Green and Quinoa Taco or Burrito Filling, 32 Collard Greens Wrapped Rolls with Spiced Quinoa Filling, 33 Mediterranean Greens, 34 Smoky Collard Greens, 35 Horseradish and Cannellini Bean Dip, 36 Kale-Apple Slaw with Goji Berry Dressing, 37 Hail to the Kale Salad, 38 Kid’s Kale, 39 The Veggie Queen’s Husband’s Daily Green Smoothie, 40 The Veggie Queen’s Raw Kale Salad, 41 Crunchy Kohlrabi Quinoa Salad, 42 Balsamic Glazed Herb Roasted Roots with Kohlrabi, -

Leafy Greens Basics E Low in Calorie Beet Greens Ns Ar S and Ree Sod Y G R Minerals, Vita Iu Kale Af Othe Mins M Le in an , Gh D Hi fib T E U R B

Leafy Greens Basics are low in calories a Beet Greens ens nd s gre od Kale fy er minerals, vitam ium ea oth ins , L in an gh d hi fib t e u r b . Spinach Collard Chard Greens Bok Choy Turnip Mustard Greens Greens Shop and Save < Choose greens that look Store Well crisp. Avoid wilted or yellowing leaves and browned stalks. Waste Less < Greens may be fresher and cost less when they are in I Wrap greens in a damp season. Most are available paper towel and refrigerate spring through summer or fall. in an open plastic bag or Kale, mustard greens and container. Use most greens collard greens are available within 5 to 7 days for best 3. Lift leaves from the water. during the winter months. quality. 4. Repeat until there is no grit < Try farm stands or farmers I Wash greens just before on the bottom of the bowl. markets for local greens in using to reduce spoilage. 5. Pat leaves dry if needed. season. 1. Swish leaves in a large bowl I Freeze for longer storage. < Frozen spinach is a good of cool water. Blanch (cook briefly) before value but other frozen greens 2. Let rest briefly to allow dirt freezing for best quality. Use often cost more than fresh. to settle. within 10 to 12 months. This material was funded by USDA’s Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP). SNAP provides nutrition assistance to people with low income. SNAP can help you buy nutritious foods for a better diet. To find out more, contact Oregon Safe Net at 211. -

Frozen Vegetables – This List Is Not All-Inclusive and Is Updated on a Regular Basis

Frozen Vegetables – This list is not all-inclusive and is updated on a regular basis. There may be products not on this list that are approved. Unit of Brand Name Description Size Measure Package Size UPC Organic Albertsons Asparagus Spears 12 Ounce 0-41163-45766-9 No Albertsons Baby Lima Beans 16 Ounce 0-41163-80164-6 No Albertsons Blackeye Peas 16 Ounce 0-41163-80300-8 No Albertsons Broccoli Cuts 32 Ounce 0-41163-80236-0 No Albertsons Broccoli Cuts 16 Ounce 0-41163-80176-9 No Albertsons Broccoli Florets 16 Ounce 0-41163-41122-7 No Albertsons Broccoli, Carrots & Water Chestnut Blend 16 Ounce 0-41163-80262-9 No Albertsons Brussels Sprouts 16 Ounce 0-41163-80180-6 No Albertsons California Blend Vegetables 16 Ounce 0-41163-80250-6 No Albertsons Cauliflower Florets 16 Ounce 0-41163-80184-4 No Albertsons Chopped Broccoli 16 Ounce 0-41163-41123-4 No Albertsons Chopped Onions 12 Ounce 0-41163-41125-8 No Albertsons Chopped Spinach 16 Ounce 0-41163-80197-4 No Albertsons Chopped Spinach 10 Ounce 0-41163-80102-8 No Albertsons Chopped Turnip Greens with Diced Turnips 16 Ounce 0-41163-80310-7 No Albertsons Corn On The Cob 8 Count 0-41163-80132-5 No Albertsons Corn On The Cob 4 Count 0-41163-80130-1 No Albertsons Country Trio Vegetables 16 Ounce 0-41163-80258-2 No Albertsons Crinkle Cut Zucchini 16 Ounce 0-41163-41000-8 No Albertsons Crinkle Sliced Carrots 16 Ounce 0-41163-80188-2 No Albertsons Cut Corn 64 Ounce 0-41163-80242-1 No Albertsons Cut Corn 32 Ounce 0-41163-80224-7 No Albertsons Cut Corn 16 Ounce 0-41163-80146-2 No Albertsons Cut Corn 10 Ounce 0-41663-80114-1 No Albertsons Cut Green Beans 28 Ounce 0-41163-41022-0 No Albertsons Cut Green Beans 16 Ounce 0-41163-80160-8 No Albertsons Cut Green Beans 12 Ounce 0-41163-45698-3 No Albertsons Cut leaf spinach 16 Ounce 0-41163-80196-7 No Updated 4-2-2014 Frozen Vegetables – This list is not all-inclusive and is updated on a regular basis. -

Myplate—The Vegetable Group

COLLEGE OF AGRICULTURAL, CONSUMER AND ENVIRONMENTAL SCIENCES MyPlate—The Vegetable Group: Vary Your Veggies Revised by Raquel Garzon1 aces.nmsu.edu/pubs • Cooperative Extension Service • Guide E-139 The College of Agricultural, Consumer and Environmental Sciences is an engine for economic and community | Dreamstime.com © Elena Veselova development in New INTRODUCTION The vegetable group includes vegetables and 100% Mexico, improving vegetable juices. Vegetables can be eaten raw or cooked and are available fresh, frozen, canned, or dried/dehydrated. They can be eaten whole, cut up, the lives of New or mashed. Vegetables are naturally low in calories and fat, and are free of cholesterol. Vegetables are di- Mexicans through vided into five subgroups depending on their nutrient content: dark green, red and orange, dry beans and academic, research, peas, starch, and other. MyPlate recommends a variety of vegetables, espe- cially dark green and red and orange vegetables, as well as beans and peas. Eating a diet rich in vegetables and fiber as part of a healthy diet may re- and Extension duce the risk of heart disease and certain types of cancer. It can also reduce the risk of developing obesity and type 2 diabetes. programs. NUTRIENTS IN THE VEGETABLE GROUP The following nutrients are found in most vegetables. A typical American diet is at risk for being low in nutrients marked with an asterisk (*). *Fiber helps reduce blood cholesterol levels, may reduce the risk of heart disease, and promotes proper bowel function. Fiber can also promote the existence of good bacteria in our digestive tract. Fiber-containing foods such as vegetables help provide a feeling of fullness with fewer calories. -

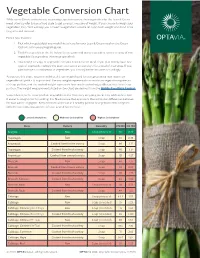

OPTAVIA® Vegetable Conversion Chart

Vegetable Conversion Chart While some Clients prefer to use measuring cups to measure their vegetables for the Lean & Green meal, others prefer to use a food scale to get an exact measure of weight. If you choose to weigh your vegetables, this chart will help you convert a vegetable’s volume (in cups) to its weight on a food scale (in grams and ounces). Here's how it works: 1. Pick which vegetable(s) you would like to have for your Lean & Green meal on the Green Options list in your program guide. 2. Find the vegetable in the list below for the gram and ounce equivalent to one serving of that vegetable (½ cup unless otherwise specified). 3. You need 3 servings of vegetables for your Lean & Green meal. If you plan to only have one type of vegetable, multiply the gram and ounce amount by 3 for a total of 3 servings. If you plan to have a combination of vegetables, you can adjust the amounts accordingly. As you use this chart, keep in mind that the raw weight listed is not representing how much raw vegetable will yield a ½ cup cooked. The raw weight represents how much raw vegetable equates to a ½ cup portion, and the cooked weight represents how much cooked vegetable equates to a ½ cup portion. The weight measurements listed on the chart are derived from the USDA’s FoodData Central. Some Clients prefer to weigh their vegetables in the form they are going to eat it in, while others find it easier to weigh prior to cooking. -

Variation in Plant- Herbivore

THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES ASSOCIATIONAL EFFECTS: VARIATION IN PLANT- HERBIVORE INTERACTION AT DIFFERENT DISTANCES OF HETEROSPECIFIC PLANTS By KYLE H. SPELLS A Thesis submitted to the Department of Biological Science in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation with Honors in the Major Degree Awarded: Fall, 2016 Associational Effects: Variation in Plant-Herbivore Interaction at Different Distances of Heterospecific Plants Kyle H. Spells, Brian D. Inouye, Nora Underwood Department of Biological Science, Florida State University, Tallahassee, FL, 32306, U.S.A. Abstract: Certain plants are known to influence pest attack on other plants in a phenomenon termed “associational effects” (AE). AE has long been exploited in agriculture by means of companion planting or intercropping, where one or more species in a polyculture of plants confers indirect benefits to another. Many plants in these types of interactions emit volatile compounds that effectively repel insect pests from themselves and surrounding plants (Held, Gonsiska & Potter 2003). Giant red mustard greens have been shown to be an effective neighbor plant using this mechanism, significantly reducing whitefly oviposition on focal collard greens in a greenhouse experiment (Legaspi 2010). However, collards planted in a field 2.4m – 12.2m away from a central mustard plot did not significantly affect attraction or oviposition of whiteflies in the same study. Given these inconsistent results, it is possible that collards planted in the field experiment were too far from the mustard plot to experience repellent effects. The goal of this study was to to determine if AE on collard greens from mustard greens depend on the distance between plants. -

Orecchiette Alle Cime Di Rapa Orecchiette with Broccoli Rabe (Serves 4 People)

Orecchiette Alle Cime di Rapa Orecchiette with Broccoli Rabe (serves 4 people) Ingredients: • 14 oz of "orecchiette" pasta or gluten-free rotini • 2.5 lb of broccoli rabe (rapini) • 3 mid-size sausages or sausage meat (optional) • 2 oz of anchovies • Grated Parmiggiano Reggiano (whole wedge) or Grana Padano cheese • Extra virgin olive oil (EVOO) • 2 gloves of garlic • Salt (coarse and fine) • Pepper (pepper flakes, small fresh red pepper or black ground pepper) Tools Needed: • Large pot to cook the pasta • Large/deep sauté or frying pan for the sauce • Skimmer spoon/strainer (to remove the rapini and pasta from boiling water) • Ladle for the pasta water • Wooden spoon or spatula for stirring sauce • Medium bowl (for boiled rapini) Cooking Directions: • Bring a large pot of water to boil • Wash your rapini and take off the leaves/flower of the rapini from the stem & set aside • Discard stems or peel & chop up to add to the leaves (this is time consuming) • Add 1 palmful of coarse salt to the water once boiling (flavors the rapini and pasta!) • Cook the leaves/flower of the rapini in the boiling water for 2-3 minutes and put them aside (keep the same boiling water to cook the pasta) • While the rapini is boiling, put EVOO to cover bottom of large sauté pan and cook over medium heat • While pan is heating, peel and chop the garlic and pepper if using • Gently fry the garlic and pepper over medium heat until light brown • Once the rapini is removed from the boiling water, add the pasta, and cook till “very al dente” • Push browned garlic