Submission DR159

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

State Budget 2010–11 Capital Statement Budget Paper No.3 State Budget 2010–11 Capital Statement Budget Paper No.3

State Budget 2010–11 Capital Statement Budget Paper No.3 State Budget 2010–11 Budget State Capital Statement Budget Paper No.3 Paper Budget Statement Capital State Budget 2010–11 Capital Statement Budget Paper No.3 www.budget.qld.gov.au 2010–11 State Budget Papers 1. Budget Speech 2. Budget Strategy and Outlook 3. Capital Statement 4. Budget Measures 5. Service Delivery Statements Budget Highlights This suite of Budget Papers is similar to that published in 2009–10. The Budget Papers are available online at www.budget.qld.gov.au. They can be purchased through the Queensland Government Bookshop – individually or as a set – by phoning 1800 801 123 or at www.bookshop.qld.gov.au © Crown copyright All rights reserved Queensland Government 2010 Excerpts from this publication may be reproduced, with appropriate State Budget 2010–11 acknowledgement, as permitted under the Copyright Act. Capital Statement Budget Paper No.3 Capital Statement www.budget.qld.gov.au Budget Paper No.3 ISSN 1445-4890 (Print) ISSN 1445-4904 (Online) STATE BUDGET 2010-11 CAPITAL STATEMENT Budget Paper No. 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Overview Introduction .................................................................................. 2 Capital Grants to Local Government Authorities.......................... 5 Funding the State Capital Program.............................................. 6 2. State Capital Program - Planning and Priorities Introduction .................................................................................11 Capital Planning and Priorities....................................................11 -

Water for Life

SQWQ.001.002.0382 • se a er WATER FOR LIFE • Strategic Plan 2010-11 to 2014-15 Queensland Bulk Water Supply Authority (QBWSA) trading as Seqwater 1 SQWQ.001.002.0383 2010-11 to 2014-15 Strategic Plan Contents Foreword ........................................................................................................................................................... 3 Regional Water Grid ......................................................................................................................................... 4 . Seqwater's vision and mission ......................................................................................................................... 5 Our strategic planning framework ................................................................................................................... 5 Emerging strategic issues ................................................................................................................................ 7 Seqwater's goals and strategy for 2010-11 to 2014-15 ................................................................................... 8 • Budget outlook............................................................................................................................................... 10 Strategic performance management ................................................................................................................. 11 Key Performance Indicators .......................................................................................................................... -

Water for South East Queensland: Planning for Our Future ANNUAL REPORT 2020 This Report Is a Collaborative Effort by the Following Partners

Water for South East Queensland: Planning for our future ANNUAL REPORT 2020 This report is a collaborative effort by the following partners: CITY OF LOGAN Logo guidelines Logo formats 2.1 LOGO FORMATS 2.1.1 Primary logo Horizontal version The full colour, horizontal version of our logo is the preferred option across all Urban Utilities communications where a white background is used. The horizontal version is the preferred format, however due to design, space and layout restrictions, the vertical version can be used. Our logo needs to be produced from electronic files and should never be altered, redrawn or modified in any way. Clear space guidelines are to be followed at all times. In all cases, our logo needs to appear clearly and consistently. Minimum size 2.1.2 Primary logo minimum size Minimum size specifications ensure the Urban Utilities logo is reproduced effectively at a small size. The minimum size for the logo in a horizontal format is 50mm. Minimum size is defined by the width of our logo and size specifications need to be adhered to at all times. 50mm Urban Utilities Brand Guidelines 5 The SEQ Water Service Provider Partners work together to provide essential water and sewerage services now and into the future. 2 SEQ WATER SERVICE PROVIDERS PARTNERSHIP FOREWORD Water for SEQ – a simple In 2018, the SEQ Water Service Providers made a strategic and ambitious statement that represents decision to set out on a five-year journey to prepare a holistic and integrated a major milestone for the plan for water cycle management in South East Queensland (SEQ) titled “Water region. -

Record of Proceedings

PROOF ISSN 1322-0330 RECORD OF PROCEEDINGS Hansard Home Page: http://www.parliament.qld.gov.au/hansard/ E-mail: [email protected] Phone: (07) 3406 7314 Fax: (07) 3210 0182 Subject FIRST SESSION OF THE FIFTY-THIRD PARLIAMENT Page Tuesday, 14 February 2012 ASSENT TO BILLS .............................................................................................................................................................................. 1 Tabled paper: Letter, dated 6 December 2011, from Her Excellency the Governor to Mr Speaker advising of assent to bills on 6 December 2011. ............................................................................................................................ 1 REPORT ............................................................................................................................................................................................... 1 Expenditure of the Office of the Speaker ................................................................................................................................. 1 Tabled paper: Statement for Public Disclosure: Expenditure of the Office of the Speaker of the Legislative Assembly for the period 1 July 2011 to 31 December 2011......................................................................................... 1 PRIVILEGE ........................................................................................................................................................................................... 2 Speaker’s -

Water for Life Your Say on South East Queensland's Water Future

Your say on South East Queensland’s water future Water for life 2015 – 2045 A Queensland Bulk Water Supply Authority, trading as Seqwater. ABN: 75 450 239 876 Level 8 117 Brisbane Street, Ipswich QLD 4305 PO Box 16146 City East QLD 4002 P 1800 771 497 F +61 7 3229 7926 E [email protected] W seqwater.com.au Translation and interpreting assistance Seqwater is committed to providing accessible services to people from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds. Please contact us and we will arrange an interpreter to share this publication with you. ISBN-13:978-0-9943790-1-6 © Seqwater 2015 This publication is correct at time of writing and is subject to change. B Water for life Water gives and sustains life. It supports healthy communities and a prosperous South East Queensland (SEQ). It is an essential service that is delivered to 3.1 million people across our region every day. As the region’s bulk water supply authority, we are committed to water for life. We are charged with delivering safe, secure and cost-effective water and catchment services to our customers and communities today and in the future. In SEQ we live in a climate of extremes – from times of drought to floods – and we need to be ready to adjust our water use and management when conditions change. Our research tells us that apart from a severe drought or a sharp increase in demand, we have enough water to supply our region for about 15 years. But after that, we will need new water sources to meet growing demand. -

The Queensland Urban Water Industry Workforce Composition Snapshot Contents

The Queensland Urban Water Industry Workforce Composition Snapshot Contents 1 Introduction 1 1.1 Queensland Water Industry 1 1.2 What is a Skills Formation Strategy 2 2 Size of the Queensland Water Industry 3 2.1 Section Summary 3 2.2 Background 3 2.3 Total Size of the Local Government Water Industry 4 2.4 Size of the Broader Queensland Water Industry 5 3 Internal Analysis: Workforce Statistics 6 3.1 Section Summary 6 3.2 Background 6 is a business unit of the 3.3 Job Family/Role 7 Institute of Public Works Engineers Association 3.4 Age 8 Queensland (IPWEAQ) 3.5 Age Profile and Job Role 9 and an initiative of Institute 3.6 Comparison of Queensland Local Government of Public Works Engineering owned Water Service Providers, SEQ Water Grid Australia QLD Division Inc and WSAA study workforce statistics 10 Local Government Association of QLD 4 Discussion and Conclusion 11 Local Government References 12 Managers Australia Appendix 13 Australian Water Association This document can be referenced as the ‘Queensland Urban Water Industry Workforce Snapshot 2010’ 25 Evelyn Street Newstead, QLD, 4006 PO Box 2100 Fortitude Valley, BC, 4006 phone 07 3252 4701 fax 07 3257 2392 email [email protected] www.qldwater.com.au 1 Introduction Queensland is mobilising its water industry to respond to significant skills challenges including an ageing workforce and competition from other sectors. 1.1 Queensland Water Industry In Queensland, there are 77 standard registered water service providers, excluding smaller boards and private schemes. Of these, 66 are owned by local government, 15 utilities are indigenous councils including 2 Torres Strait Island councils and 13 Aboriginal councils. -

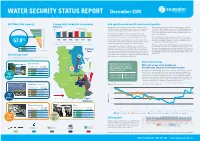

WATER SECURITY STATUS REPORT December 2020

WATER SECURITY STATUS REPORT December 2020 SEQ Water Grid capacity Average daily residential consumption Grid operations and overall water security position (L/Person) Despite receiving rainfall in parts of the northern and southern areas The Southern Regional Water Pipeline is still operating in a northerly 100% 250 2019 December average of South East Queensland (SEQ), the region continues to be in Drought direction. The Northern Pipeline Interconnectors (NPI 1 and 2) have been 90% 200 Response conditions with combined Water Grid storages at 57.8%. operating in a bidirectional mode, with NPI 1 flowing north while NPI 80% 150 2 flows south. The grid flow operations help to distribute water in SEQ Wivenhoe Dam remains below 50% capacity for the seventh 70% 100 where it is needed most. SEQ Drought Readiness 50 consecutive month. There was minimal rainfall in the catchment 60% average Drought Response 0 surrounding Lake Wivenhoe, our largest drinking water storage. The average residential water usage remains high at 172 litres per 50% person, per day (LPD). While this is less than the same period last year 40% 172 184 165 196 177 164 Although the December rain provided welcome relief for many of the (195 LPD), it is still 22 litres above the recommended 150 LPD average % region’s off-grid communities, Boonah-Kalbar and Dayboro are still under 57.8 30% *Data range is 03/12/2020 to 30/12/2020 and 05/12/2019 to 01/01/2020 according to the SEQ Drought Response Plan. drought response monitoring (see below for additional details). 20% See map below and legend at the bottom of the page for water service provider information The Bureau of Meteorology (BOM) outlook for January to March is likely 10% The Gold Coast Desalination Plant (GCDP) had been maximising to be wetter than average for much of Australia, particularly in the east. -

Case Study Site Based Competency Assessment for Drinking Water Operators

Case Study Site Based Competency Assessment for Drinking Water Operators Technical Competency Project Supporters Introduction Evaluation and Verification of Operator Competency This case study describes the process of operator competency development, site-specific competency evaluation and ongoing skills development at Queensland Bulk Water Supply Authority QBWSA, operating as Seqwater. This is illustrated through Seqwater’s training program for Water Treatment Plant (WTP) operators, which involves; development, support and growth of operator competence. A key feature of the training program is the use of a Site Based Competency Assessment (SBCA) for WTP operators, which have also been developed for other operational functions in dam and catchment operations at Seqwater. These SBCAs have been developed as an important step in the recognition of the skills, knowledge and experience of trained and competent operators. The support of operator competence through a formal process of site-specific competency evaluation is a progressive approach by Seqwater in supporting WTP operator competency development. The following sections of this case study describe how the Seqwater training program works, as well as analysing the benefits and identifying any future plans for improvement. Queensland Bulk Water Supply Authority (Seqwater) Seqwater was established in 1 July 2008 through the South East Queensland Water (Restructuring) Act 2007. In January 2013, further legislative changes gave Seqwater the management, operation and maintenance of bulk drinking water pipelines previously provided by LinkWater; the water grid management services provided by the SEQ Water Grid Manager; and the long-term planning functions of the region’s future water needs Seqwater is the Queensland Government statutory authority responsible for providing a safe, secure and cost-effective bulk drinking water supply for 3.1 million people across the South East Queensland region (Figure C3.1). -

Rising to the Challenge

Rising to the challenge Annual Report 2010-11 14 September 2011 This Annual Report provides information about the financial and non-financial performance of Seqwater for 2010-11. The Hon Stephen Robertson MP It has been prepared in accordance with the Financial Minister for Energy and Water Utilities Accountability Act 2009, the Financial and Performance PO Box 15216 Management Standard 2009 and the Annual Report City East QLD 4002 Guidelines for Queensland Government Agencies. This Report records the significant achievements The Hon Rachel Nolan MP against the strategies and activities detailed in the Minister for Finance, Natural Resources and the Arts organisation’s strategic and operational plans. GPO Box 611 This Report has been prepared for the Minister for Brisbane QLD 4001 Energy and Water Utilities to submit to Parliament. It has also been prepared to meet the needs of Seqwater’s customers and stakeholders, which include the Federal and local governments, industry Dear Ministers and business associations and the community. 2010-11 Seqwater Annual Report This Report is publically available and can be viewed I am pleased to present the Annual Report 2010-11 for and downloaded from the Seqwater website at the Queensland Bulk Water Supply Authority, trading www.seqwater.com.au/public/news-publications/ as Seqwater. annual-reports. I certify that this Annual Report meets the prescribed Printed copies are available from Seqwater’s requirements of the Financial Accountability Act 2009 registered office. and the Financial and Performance Management Standard 2009 particularly with regard to reporting Contact the Authority’s objectives, functions, performance and governance arrangements. Queensland Bulk Water Authority, trading as Seqwater. -

KEY POINTS • on the 1 October 2010, Wivenhoe Dam Reached 100 Per Cent for the First Time Since 2001

Department of Environment and Resource Management - Parliamentary Briefing Note To Minister Robertson Prepared for Parliamentary sittings 5 -7 October 2010 WIVENHOE DAM SPILLING - the likelihood of Wivenhoe Dam spilling and safety KEY POINTS • On the 1 October 2010, Wivenhoe Dam reached 100 per cent for the first time since 2001. c • After the weekend's weather, the dam reached 101 per cent on Monday. • On Monday 4 October, Seqwater commenced controlled increased releases from Wivenhoe Dam through the hydro- electric plant in the dam wall. • Even with substantial rain, Wivenhoe Dam's flood capacity is equal to 3 times Sydney harbour - or - 1.45 million megalitres. • Releases from Somerset Dam into Wivenhoe Dam via the cone valves ceased over the weekend. • Seqwater has a Dam Safety Management Program and a Flood Control Centre. The program ensures that each of its dams is operated and maintained in a manner that is both safe and minimises the risks associated with a dam failure and flood events, including working with local councils and emergency services. Contact: Dan Spiller Approved: Mike Lyons, Director, SEQ Water Grid Comms Telephone: Approved: [Insert title of ADG or DOG] Date: 4 October 2010 Approved: Director-General CTS No. 17669/10 1 RESPONSE • On the 1 October 2010 Wivenhoe Dam reached 100 per cent for the first time since 2001. • After the weekend's weather, the dam reached 101 per cent on Monday 4 October 2010. • The trigger level for full gate releases for Wivenhoe Dam is 102.5 per cent. • Also on Monday 4 October, Seqwater commenced controlled C increased release from Wivenhoe Dam through the hydro- electric plant in the dam wall. -

Resilience of Water Supply Systems in Meeting the Challenges Posed by Climate Change and Population Growth

RESILIENCE OF WATER SUPPLY SYSTEMS IN MEETING THE CHALLENGES POSED BY CLIMATE CHANGE AND POPULATION GROWTH Pradeep Amarasinghe BSc.Engineering (Civil) MEng. (Water Management) A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIRMENTS OF THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY SCIENCE AND ENGINEERING FACULTY QUEENSLAND UNIVERSITY OF TECHNOLOGY 2014 Keywords Resilience, Potable water supply, Meta-system, Climate change, Population growth, System Dynamics modeling, Indicators ii Abstract This research study focused on an investigation of resilience of water supply systems to climate change and population growth impacts. A water supply system is a complex system which encompasses a diverse set of subsystems which lie on socio- ecological and technical domains. The interrelationships among these subsystems dictate the characteristics of the overall water supply system. Climate change and population growth are two issues that create qualitative and quantitative impacts on surface water resources that influence the functions of a water supply system. Due to the complexity of a water supply system and the dependability of water on climate conditions, provision of a reliable potable water supply is a challenge. Therefore, effective management of water supply is a key pre-requisite. For achieving management goals in complex systems, complex procedures may be required. Depending on uncertain climatic conditions, one approach to satisfy demand on a water supply system is to expand the system by building new infrastructure. That is a part of a supply side improvement and management process. A completely different approach is to understand the system components, especially their characteristics and capabilities, in order to manage the relationships between them and make use of that knowledge to manipulate management strategies to achieve maximum efficiencies, thus obviating the need to resort to the commonly adopted option of new infrastructure provision. -

Annual Report 2008/09

SQWQ.001.002.0286 annual report 2008/09 • SQWQ.001.002.0287 SQWQ.001.002.0288 • Contents R~port from the Chairman and CEO 2 Governance 20 About Seqwater 4 Organisational structure 20' Tha South East Queensland ISE91 Orgar:Jisational review n Water Grid 6 Executive lea~ership team 22 The YO,ar In review 8 Related entities 22 Seqwater Board 22 Vision and Mission 10 Responsible Ministers 24 Vision 10 Board role 25 Mission 10 Board committees 25 • Sustainable catchments 10 Board attendance 26 Strategic goals and performance 13 Board remuneration 27 ~ey Performance Indicator summary 15 Strategic and operational planning 27 Risk management 28 Summary of financial Internal audit 28 information 2008~D9 17 Information systems and record keeping 28 Key financial ratios 17 Workforce planning and retention 29 Summary of major assets 18 Conduct and ethics 29 Dams 18 Whistleblower protection 29 Water Treatment Plants 18 Consultancy 31 Overseas travel 31 Greenhouse gas emissions 32 Legislative and policy requirements 32 Glossary 34 Financial Report 37 QUEENSLAND BULK WATER SUPPLY AUTHORITY IQ8WSAJ TRADING AS SEaWATER ANNUAL REPORT 2008/09 SQWQ.001.002.0289 Ann~belLe Chaplain Peter Borrows • Report'from the 2 Chairman and CEO As the Statutory Authonty for bulk water While the rain and Increase In storage supply and catchment management. Seqwater levels brought welcome relief With many of made good progress this year In helping to Seqwater"s dams overflOWing In spectacular secure safe and reliable water supplies for fashIOn, they In fact serve as a reminder of the South East Queensland. challenges associated With more extreme and unpredICtable weather The 2008·09 year marked the first futl year 01 operation as Seqwater, following the July An equally challenging and Immediate 1 2008 Implementation of water Industry pnonty this year has been to bring together reforms under the South East Queensland the vanous water entity assets and staff that Water Restructuring Act 200? compnse the new Seqwater bUSiness.