Maroon Intellectuals from the Caribbean and the Sources of Their Communication Strategies, 1925-1940

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Claude Mckay's a Long Way from Home

Through a Black Traveler's Eyes: Claude McKay's A Long Way from Home Tuire Valkeakari Yale University Abstract: This essay analyzes Jamaican-born Claude McKay's discussion of racism(s) and nationalism(~) in his travelogue/autobiography A Long Way from Home ( 1937), in which he chronicles his sojourn in Europe and North Africa and addresses his complex relationship to the United States. Much of McKay's social analysis draws, as this essay establishes, on his observation that racism and nationalism tend to be intertwined and feed 011 each othe1: While describing his travels, McKay presents himselfas a bordercrosser who is "a bad nationalist" and an "internationalist" - a cosmopolitan whose home cannot be defined by any fixed national labels or by nationalist or racialist identity politics. This essay's dialogue with McKay's memoir ultimately reconstructs his difficult and of1-frustrated quest for democracy - the political condition that Ralph Ellison once eloquently equated with "man~· being at home in. the world." Key words: Claude McKay - nationalism - transnationalism - cosmopolitanism - race - racism - travel The way home we seek is that condition of man's being at home in the world, which is called love, and which we tenn democracy. - Ralph Elli son, "Brave Words for a Startling Occasion" I said I was born in the West Indies and lived in the United States and that I was an American, even though I was a British subject, but 1 preferred to think of myself as an internationalist. The chaoL1Sh said he didn't understand what was an internationalist. J laughed and said that an internationalist was a bad nationalist. -

Sylvia Pankhurst's Sedition of 1920

“Upheld by Force” Sylvia Pankhurst’s Sedition of 1920 Edward Crouse Undergraduate Thesis Department of History Columbia University April 4, 2018 Seminar Advisor: Elizabeth Blackmar Second Reader: Susan Pedersen With dim lights and tangled circumstance they tried to shape their thought and deed in noble agreement; but after all, to common eyes their struggles seemed mere inconsistency and formlessness; for these later-born Theresas were helped by no coherent social faith and order which could perform the function of knowledge for the ardently willing soul. Their ardor alternated between a vague ideal and the common yearning of womanhood; so that the one was disapproved as extravagance, and the other condemned as a lapse. – George Eliot, Middlemarch, 1872 Table of Contents Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................... 2 Abbreviations ............................................................................................................................ 3 Introduction .............................................................................................................................. 4 The End of Edwardian England: Pankhurst’s Political Development ................................. 12 After the War: Pankhurst’s Collisions with Communism and the State .............................. 21 Appealing Sedition: Performativity of Communism and Suffrage ....................................... 33 Prison and Release: Attempted Constructions of Martyrology -

D. H. Lawrence and the Harlem Renaissance

‘You are white – yet a part of me’: D. H. Lawrence and the Harlem Renaissance A thesis submitted to The University of Manchester for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Humanities 2019 Laura E. Ryan School of Arts, Languages and Cultures 2 Contents Abstract ...................................................................................................................... 3 Declaration ................................................................................................................. 4 Copyright statement ................................................................................................... 5 Acknowledgements .................................................................................................... 6 Introduction ................................................................................................................ 7 Chapter 1: ‘[G]roping for a way out’: Claude McKay ................................................ 55 Chapter 2: Chaos in Short Fiction: Langston Hughes ............................................ 116 Chapter 3: The Broken Circle: Jean Toomer .......................................................... 171 Chapter 4: ‘Becoming [the superwoman] you are’: Zora Neale Hurston................. 223 Conclusion ............................................................................................................. 267 Bibliography ........................................................................................................... 271 Word Count: 79940 3 -

Black Internationalism and African and Caribbean

BLACK INTERNATIONALISM AND AFRICAN AND CARIBBEAN INTELLECTUALS IN LONDON, 1919-1950 By MARC MATERA A Dissertation submitted to the Graduate School-New Brunswick Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Program in History Written under the direction of Professor Bonnie G. Smith And approved by _______________________ _______________________ _______________________ _______________________ New Brunswick, New Jersey May 2008 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Black Internationalism and African and Caribbean Intellectuals in London, 1919-1950 By MARC MATERA Dissertation Director: Bonnie G. Smith During the three decades between the end of World War I and 1950, African and West Indian scholars, professionals, university students, artists, and political activists in London forged new conceptions of community, reshaped public debates about the nature and goals of British colonialism, and prepared the way for a revolutionary and self-consciously modern African culture. Black intellectuals formed organizations that became homes away from home and centers of cultural mixture and intellectual debate, and launched publications that served as new means of voicing social commentary and political dissent. These black associations developed within an atmosphere characterized by a variety of internationalisms, including pan-ethnic movements, feminism, communism, and the socialist internationalism ascendant within the British Left after World War I. The intellectual and political context of London and the types of sociability that these groups fostered gave rise to a range of black internationalist activity and new regional imaginaries in the form of a West Indian Federation and a United West Africa that shaped the goals of anticolonialism before 1950. -

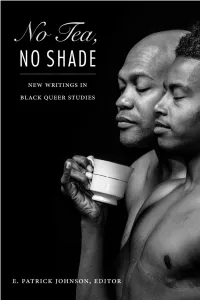

NO TEA, NO SHADE This Page Intentionally Left Blank No Tea, NO SHADE

NO TEA, NO SHADE This page intentionally left blank No Tea, NO SHADE New Writings in Black Queer Studies EDITED BY E. Patrick Johnson duke university press Durham & London 2016 © 2016 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of Amer i ca on acid- free paper ∞ Typeset in Adobe Caslon by Westchester Publishing Services Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Names: Johnson, E. Patrick, [date] editor. Title: No tea, no shade : new writings in Black queer studies / edited by E. Patrick Johnson. Description: Durham : Duke University Press, 2016. | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: lccn 2016022047 (print) lccn 2016023801 (ebook) isbn 9780822362227 (hardcover : alk. paper) isbn 9780822362425 (pbk. : alk. paper) isbn 9780822373711 (e- book) Subjects: lcsh: African American gays. | Gay and lesbian studies. | African Americans in popu lar culture. | Gays in popu lar culture. | Gender identity— Political aspects. | Sex in popu lar culture. Classification: lcc e185.625.n59 2016 (print) | lcc e185.625 (ebook) | ddc 306.76/608996073— dc23 lc rec ord available at https:// lccn . loc . gov / 2016022047 Cover art: Philip P. Thomas, Sharing Tea, 2016. © Philip P. Thomas. FOR ALL THE QUEER FOREMOTHERS AND FOREFATHERS This page intentionally left blank CONTENTS foreword Cathy J. Cohen xi acknowl edgments xv introduction E. Patrick Johnson 1 CHAPTER 1. Black/Queer Rhizomatics Train Up a Child in the Way Ze Should Grow . JAFARI S. ALLEN 27 CHAPTER 2. The Whiter the Bread, the Quicker You’re Dead Spectacular Absence and Post-Racialized Blackness in (White) Queer Theory ALISON REED 48 CHAPTER 3. Troubling the Waters Mobilizing a Trans* Analytic KAI M. -

A Critical and Comparative Analysis of Organisational Forms of Selected Marxist Parties, in Theory and in Practice, with Special Reference to the Last Half Century

Rahimi, M. (2009) A critical and comparative analysis of organisational forms of selected Marxist parties, in theory and in practice, with special reference to the last half century. PhD thesis. http://theses.gla.ac.uk/688/ Copyright and moral rights for this thesis are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Glasgow Theses Service http://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] A critical and comparative analysis of organisational forms of selected Marxist parties, in theory and in practice, with special reference to the last half century Mohammad Rahimi, BA, MSc Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of PhD Centre for the Study of Socialist Theory and Movement Faculty of Law, Business and Social Science University of Glasgow September 2008 The diversity of the proletariat during the final two decades of the 20 th century reached a point where traditional socialist and communist parties could not represent all sections of the working class. Moreover, the development of social movements other than the working class after the 1960s further sidelined traditional parties. The anti-capitalist movements in the 1970s and 1980s were looking for new political formations. -

"A Road to Peace and Freedom": the International Workers Order and The

“ A ROAD TO PEACE AND FREEDOM ” Robert M. Zecker “ A ROAD TO PEACE AND FREEDOM ” The International Workers Order and the Struggle for Economic Justice and Civil Rights, 1930–1954 TEMPLE UNIVERSITY PRESS Philadelphia • Rome • Tokyo TEMPLE UNIVERSITY PRESS Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19122 www.temple.edu/tempress Copyright © 2018 by Temple University—Of The Commonwealth System of Higher Education All rights reserved Published 2018 All reasonable attempts were made to locate the copyright holders for the materials published in this book. If you believe you may be one of them, please contact Temple University Press, and the publisher will include appropriate acknowledgment in subsequent editions of the book. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Zecker, Robert, 1962- author. Title: A road to peace and freedom : the International Workers Order and the struggle for economic justice and civil rights, 1930-1954 / Robert M. Zecker. Description: Philadelphia : Temple University Press, 2018. | Includes index. Identifiers: LCCN 2017035619| ISBN 9781439915158 (cloth : alk. paper) | ISBN 9781439915165 (paper : alk. paper) Subjects: LCSH: International Workers Order. | International labor activities—History—20th century. | Labor unions—United States—History—20th century. | Working class—Societies, etc.—History—20th century. | Working class—United States—Societies, etc.—History—20th century. | Labor movement—United States—History—20th century. | Civil rights and socialism—United States—History—20th century. Classification: LCC HD6475.A2 -

BIBLIOGRAPHY General Issues

IRSH 57 (2012), pp. 317–346 doi:10.1017/S002085901200034X r 2012 Internationaal Instituut voor Sociale Geschiedenis BIBLIOGRAPHY General Issues SOCIAL THEORY AND SOCIAL SCIENCE BANAJI,JAIRUS. Theory as History. Essays on Modes of Production and Exploitation. [Historical Materialism Book Series, Vol. 25.] Brill, Leiden [etc.] 2010. xix, 406 pp. h 99.00; $141.00. Key themes in the eleven essays in this collection, seven of which are reprints of previously published papers, are the Marxist notion of a ‘‘mode of production’’; the emergence of medieval relations of production; the origins of capitalism; the dichotomy between free and unfree labour; and themes in agrarian history ranging from Byzantine Egypt to nineteenth- century colonialism. In the introductory chapter the author suggests how historical materialists might develop an alternative to Marx’s ‘‘Asiatic mode of production’’. CHRISTOYANNOPOULOS,ALEXANDRE J.M.E. Christian Anarchism. A Political Commentary on the Gospel. Imprint Academic, Exeter 2010. viii, 336 pp. £40.00; $80.00. The aim of this book, a revised version of a doctoral thesis (University of Kent, 2008), is to outline an overall theory of Christian anarchism by weaving together the different threads presented by individual Christian anarchist thinkers. After introducing the main proponents of Christian anarchist thought (e.g. Leo Tolstoy, Nicolas Berdyaev, Jacques Ellul, Vernard Eller, Michael C. Elliott, Dave Andrews, writers involved in the Catholic Worker movement and Christian anarcho-capitalists), Dr Christoyannopoulos discusses the Christian anarchist critique of and response to the state. New Perspectives on Anarchism. Ed. by Nathan J. Jun and Shane Wahl. Lexington Books, Lanham [etc.] 2010. -

The London School of Economics and Political Science

1 The London School of Economics and Political Science British Opinion and Policy towards China, 1922-1927 Phoebe Chow A thesis submitted to the Department of International History of the London School of Economics for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, London, November 2011 2 Declaration I certify that the thesis I have presented for examination for the PhD degree of the London School of Economics and Political Science is solely my own work other than where I have clearly indicated that it is the work of others (in which case the extent of any work carried out jointly by me and any other person is clearly identified in it). The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. Quotation from it is permitted, provided that full acknowledgement is made. This thesis may not be reproduced without the prior written consent of the author. I warrant that this authorisation does not, to the best of my belief, infringe the rights of any third party. Phoebe Chow 3 Abstract Public opinion in Britain influenced the government’s policy of retreat in response to Chinese nationalism in the 1920s. The foreigners’ rights to live, preach, work and trade in China extracted by the ‘unequal treaties’ in the nineteenth century were challenged by an increasingly powerful nationalist movement, led by the Kuomintang, which was bolstered by Soviet support. The Chinese began a major attack on British interests in June 1925 in South China and continued the attack as the Kuomintang marched upward to the Yangtze River, where much of British trade was centred. -

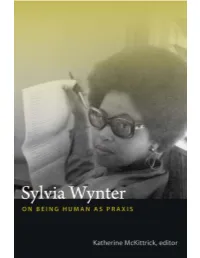

Katherine-Mckittrick-Sylvia-Wynter-On

Sylvia Wynter Sylvia Wynter ON BEING HUMAN AS PRAXIS Katherine McKittrick, ed. Duke University Press Durham and London 2015 © 2015 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid- free paper ∞ Designed by Heather Hensley Typeset in Arno Pro by Graphic Composition, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Sylvia Wynter : on being human as praxis / Katherine McKitrick, ed. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. isbn 978- 0- 8223- 5820- 6 (hardcover : alk. Paper) isbn 978- 0- 8223- 5834- 3 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Wynter, Sylvia. 2. Social sciences—Philosophy. 3. Civilization, Modern—Philosophy. 4. Race—Philosophy. 5. Human ecology—Philosophy. I. McKitrick, Katherine. hm585.s95 2015 300.1—dc23 2014024286 isbn 978- 0- 8223- 7585- 2 (e- book) Cover image: Sylvia Wynter, circa 1970s. Manuscripts, Archives and Rare Books Division, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Te New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations. Duke University Press gratefully acknowledges the Canadian Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (sshrc / Insight Grant) which provided funds toward the publication of this book. For Ellison CONTENTS ix ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Katherine McKitrick 1 CHAPTER 1 Yours in the Intellectual Struggle: Sylvia Wynter and the Realization of the Living Sylvia Wynter and Katherine McKitrick 9 CHAPTER 2 Unparalleled Catastrophe for Our Species? Or, to Give Humanness a Diferent Future: Conversations Denise Ferreira da Silva 90 CHAPTER 3 Before Man: -

CLR James, His Early Relationship to Anarchism and the Intellectual

This is a repository copy of A “Bohemian freelancer”? C.L.R. James, his early relationship to anarchism and the intellectual origins of autonomism. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/90063/ Version: Accepted Version Book Section: Hogsbjerg, CJ (2012) A “Bohemian freelancer”? C.L.R. James, his early relationship to anarchism and the intellectual origins of autonomism. In: Prichard, A, Kinna, R, Pinta, S and Berry, D, (eds.) Libertarian Socialism: Politics in Black and Red. Palgrave Macmillan , Basingstoke . ISBN 978-0-230-28037-3 © 2012 Palgrave Macmillan. This is an author produced version of a chapter published in Libertarian Socialism: Politics in Black and Red. Uploaded in accordance with the publisher's self-archiving policy. Reuse Unless indicated otherwise, fulltext items are protected by copyright with all rights reserved. The copyright exception in section 29 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 allows the making of a single copy solely for the purpose of non-commercial research or private study within the limits of fair dealing. The publisher or other rights-holder may allow further reproduction and re-use of this version - refer to the White Rose Research Online record for this item. Where records identify the publisher as the copyright holder, users can verify any specific terms of use on the publisher’s website. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. -

On the Ungendering of Black Life in Frantz Fanon, Sylvia Wynter, And

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School College of the Liberal Arts THE VALUE OF INVENTION: ON THE UNGENDERING OF BLACK LIFE IN FRANTZ FANON, SYLVIA WYNTER, AND HORTENSE SPILLERS A Dissertation in Philosophy and Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies by William Michael Paris © William Michael Paris Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 2018 The dissertation of William Michael Paris was reviewed and approved* by the following: Nancy Tuana Dupont/Class of 1949 Professor of Philosophy Co-Chair of Committee Dissertation Co-Advisor Robert Bernasconi Edwin Erle Sparks Professor of Philosophy and African American Studies Co-Chair of Committee Dissertation Co-Advisor Leonard Lawlor Edwin Erle Sparks Professor of Philosophy AnneMarie Mingo Assistant Professor of African American Studies and Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Amy Allen Liberal Arts Professor of Philosophy and Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Head of the Department of Philosophy *Signatures are on file in the Graduate School. ii Abstract My dissertation brings the works of Frantz Fanon, Sylvia Wynter, and Hortense Spillers together in order to argue that invention is the central motivation of their engagements with race, gender, and sexuality. Fanon, Wynter, and Spillers provide starting points from which it is possible to not only apprehend the historical experiences of the alienation of Black life under European colonialism and transatlantic slavery but also the contingencies and subsequent naturalizations of race, gender, and sexuality as ontological facts of what it means to be human. It is by revealing how race, gender, and sexuality are enmeshed in a violent system of exploitation and expropriation that the necessity of praxis and invention arises.