SNACKS for a FAT PLANET Pepsico Takes Stock of the Obesity Epidemic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Agawa Canyon Train Tour

NEW TOURS! 33 with Volume 30 January-December 2021 Welcome aboard one of the most popular train tours in North America, the Agawa Canyon Train Tour. This breathtaking journey is a one-day rail adventure into the heart of the Canadian wilderness! Through the large windows of our coaches, the beauty of the region will unfold, and you will experience the same rugged landscapes that inspired the Group of Seven to create some of Canada’s most notable landscape art. This one-day wilderness excursion will transport you 114 miles north of Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario, over towering trestles, alongside pristine northern lakes and rivers and through the awesome granite rock formations and vast mixed forests of the Canadian Shield. There’s plenty to photograph during your excursion so be sure to pack your camera! Don’t miss this NEW tour! Book Early! See page 44 AGAWA CANYON for description TRAIN TOUR Niagara Falls & PLUS, SOO LOCKS BOAT TOUR See page 53 African Safari for description Canada’s Safari CRUZ’IN THE MISSISSIPPI RIVER Adventure FROM LE CLAIRE TO DUBUQUE, IOWA See page 55 See page 59 for description for description Maine Lobster Become Tom Sawyer or Huck Finn for the day when we join our Captain and Crew Festival & for a day on the Mighty Mississippi River! You will board an authentic riverboat, the “Celebration Belle” Rocky Coast of Maine departing from , for an 11-hour cruise on the Mighty Mississippi can be what you Lemake Claire, of it, aIowa learning and cruiseexperience north or to simply Dubuque, an enjoyable Iowa. -

Donald Clark, Secretary July 14, 2011 Federal Trade Commission 600 Pennsylvania Ave., NW Washington, DC 20580 Electronic Filing

Donald Clark, Secretary July 14, 2011 Federal Trade Commission 600 Pennsylvania Ave., NW Washington, DC 20580 Electronic Filing via commentworks.com Re: Interagency Working Group on Food Marketed to Children: FTC Project No. P094513. General Comments and Comments on the Proposed Nutrition Principles and Marketing Definitions. Dear Mr. Clark: The Children’s Food and Beverage Advertising Initiative (CFBAI or Initiative) of the Council of Better Business Bureaus (BBB) appreciates the opportunity to provide comments to the Interagency Working Group (IWG) on Food Marketed to Children to help shape its recommendations in the report to Congress that is required by the 2009 Omnibus Appropriations Act. The CFBAI’s participants share the IWG and the First Lady’s goals of combating childhood obesity and are committed to being a part of the solution and supporting the efforts of parents by advertising healthier foods in child-directed advertising. We are pleased that the FTC supports self regulation efforts to address childhood obesity and recognizes that progress is being made. Below we provide an overview of our comment. Following that, Part I contains an introduction, and Part II describes the BBB and the CFBAI. Part III provides comments on the IWG’s proposed nutrition principles. It also describes new category-specific uniform nutrition criteria that the CFBAI is adopting and why they are a viable alternative to the IWG’s approach. Part IV explains why the definitions of child-directed marketing that the IWG proposes to use are vague and over broad, and why the CFBAI’s focus on advertising that is primarily directed to children under 12 is the better approach. -

Open Season on Holiday Staples

RAMS LOSE: Arizona Cardinals continue their domination in St. Louis. | 1B -?<-?< )8;L:8?,LE)8;L:8?,LE MMONDAY,ONDAY, NNovemberovember 28,28, 20112011 wwww.paducahsun.comww.paducahsun.com VVol.ol. 111515 NNo.o. 333232 Retailers Open season Airlines enjoy cut small robust on holiday staples jets as fuel weekend prices soar BY ANNE D’INNOCENZIO 50-seat jets at Barkley Associated Press will remain in service More Americans hunted for bargains over the weekend than BY JOSHUA FREED ever before as retailers lured them Associated Press online and into stores with big MINNEAPOLIS — The little discounts and an earlier-than- planes that connect America’s usual start to the holiday shop- small cities to the rest of the world ping season. are slowly being phased out. A record 226 million shoppers Airlines are getting rid of these visited stores and websites dur- planes — their least-effi cient — in ing the four-day holiday weekend response to the high cost of fuel. starting on Thanksgiving Day, up Delta, United Continental, and from 212 million last year, accord- other big airlines are expected to ing to early estimates by The Na- park, scrap or sell hundreds of jets tional Retail Federation released with 50 seats or fewer in coming on Sunday. Americans spent more, years. Small propeller planes are too: The average holiday shopper meeting the same fate. spent $398.62 over the weekend, Canadair regional jets able to up from $365.34 a year ago. carry 50 passengers have been Art and Anna Destrada from in use at Barkley Regional Air- Port Chester, N. -

Soft Drinks Trade Journal

Palatinose™ – the longer lasting energy Palatinose™ from BENEO is the only low glycemic carbohydrate for natural and prolonged energy. Functional products with Palatinose™: • Provide prolonged energy in the form of glucose • Support physical endurance • Taste as natural as sugar BENEO-Palatinit GmbH · Phone: +49 621 421-150 · [email protected] · www.beneo.com Soft Drinks Internationa l – February 2011 ConTEnTS 1 news Europe 4 Africa 8 Middle East 12 The leading English language magazine published in Europe, devoted exclusively to the Asia Pacific 14 manufacture, distribution and marketing of soft drinks, fruit juices and bottled water. Americas 16 Ingredients 18 features Juices & Juice Drinks 22 Functional Water 34 IFE 2011 46 Energy & Sports 26 Functional bottled water is poised for Claimed to be the UK’s premier food and growth reports Rob Walker, and though it drink sourcing event, more than 1,100 Waters & Water Plus Drinks 28 might appear to be a niche category, from organisations from around the world will be on show at London’s ExCel centre Carbonates a value perspective it is worthy of atten - 30 tion from major soft drinks companies. next month. Teas 31 Traditional/Functional 32 Packaging 38 Environment 42 People 44 Events 45 Dubai Drink Technology Expo 48 regulars A review of the third edition of Dubai Drink Technology Expo, which took PET Wins Again 36 Comment place at the Dubai World Trade Centre 2 Richard Corbett assesses the state of play last December. in the global packaging mix for soft drinks. BSDA 7&11 Whilst it is likely that it was a positive year for all main formats, he concludes Pro2Pac 52 From The Past 53 that PET continued to eat into the share of Co-located with IFE at London’s Excel Bubbling Up 54 other players. -

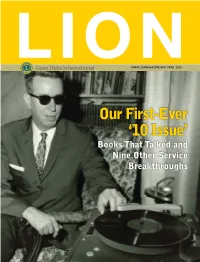

Our First-Ever '10 Issue'

WWW.LIONMAGAZINE.ORG APRIL 2013 Our First-Ever ‘10 Issue’ Books That Talked and Nine Other Service Breakthroughs Advertisement Now New & Improved The Jacuzzi® Walk-In Hot Tub… your own personal fountain of youth. The world’s leader in hydrotherapy and relaxation makes bathing safe, comfortable and affordable. emember the feeling you had the teed not to leak. The high 17” seat enables Why Jacuzzi is the Best first time you got into a hot tub? you to sit comfortably while you bathe ✓ Maximum Pain Relief - The warm water, the energizing and to access the easy-to-reach controls. R Therapeutic water AND air bubbles and the gentle hydrotherapy of Best of all, your tub comes with the jets to help you feel your best. the jets left you feeling relaxed and patented Jacuzzi® PointPro® jet system ✓ Personalized Massage - rejuvenated. Aches and pains seemed to with a new jet pattern– which gives you a New adjustable jet placement fade away, and the bubbling sound of the perfectly balanced water-to-air ratio to for pinpoint control. water helped put you in a carefree and massage you thoroughly but gently. These ✓ Easy and Safe Entry - contented mood. The first time I ever got high-volume, low-pressure pumps are Low entry, double-sealing in a hot tub at a resort, I said to myself arranged in a pattern that creates leakproof door that is easy “One of these days I’m going to have one to open and close. of these in my home– so I can experience ® Jacuzzi ✓ Comfortable Seating - this whenever I want.” Now that I’m older, Convenient 17 inch raised seat. -

University of San Diego Softball Media Guide 2007

University of San Diego Digital USD Softball (Women) University of San Diego Athletics Media Guides Spring 2007 University of San Diego Softball Media Guide 2007 University of San Diego Athletics Department Follow this and additional works at: https://digital.sandiego.edu/amg-softball Digital USD Citation University of San Diego Athletics Department, "University of San Diego Softball Media Guide 2007" (2007). Softball (Women). 18. https://digital.sandiego.edu/amg-softball/18 This Catalog is brought to you for free and open access by the University of San Diego Athletics Media Guides at Digital USD. It has been accepted for inclusion in Softball (Women) by an authorized administrator of Digital USD. For more information, please contact [email protected]. University of San Diego Archive• THE CITY... San Diego is truly "America's Finest City." A modern me tropolis (second largest in California) and a popular year round resort, San Diego spreads from the coast to the desert, including cliffs, mesas, hills, canyons and valleys. San Diego also surrounds one of California's greatest natural harbors which has been a dominant factor in determining the city's history, economy and development. Meteorologists claim San Diego as the country's only area with perfect climate. This ideal year-round environment posts an average daytime temperature of 70 degrees, with an annual rainfall average of less than 10 inches. Most days are sunny, with humidity generally low, even in the summer. The climate, attractive setting and recreational facilities make San Diego "America's Finest City." The city has mostly avoided the evils of urban sprawl, which has allowed its downtown to remain vibrant, espe cially the Gaslamp Quarter. -

Pepsico and Public Health: Is the Nation’S Largest Food Company a Model of Corporate Responsibility Or Master of Public Relations?

\\jciprod01\productn\C\CNY\15-1\CNY101.txt unknown Seq: 1 31-JUL-12 15:30 PEPSICO AND PUBLIC HEALTH: IS THE NATION’S LARGEST FOOD COMPANY A MODEL OF CORPORATE RESPONSIBILITY OR MASTER OF PUBLIC RELATIONS? By Michele Simon† INTRODUCTION While most people just think of soda when they hear the name Pepsi, the multinational conglomerate called PepsiCo is actually the largest food company in the United States and second largest in the world (Nestle´ is number one).1 PepsiCo’s dizzying reach ex- tends far beyond just fizzy sodas. Formed in 1965 through a merger of Pepsi-Cola with Frito-Lay, the company’s marriage of salty snacks with soft drinks has been key to the company’s success, and sets it apart from industry competitor Coca-Cola, which still only owns beverages.2 Over the past decade, many questions have been raised about the role of the food industry in contributing to a marketing envi- ronment in which unhealthy beverages and snacks have become the norm. While industry responses have come in various forms, PepsiCo stands out, at least in terms of public relations. The com- pany prides itself on being a leader in corporate social responsibil- ity. The goal of this article is to take a closer look at what the company says it’s doing, what it’s actually doing, and the broader context for these actions. By any measure of good health, sugary beverages and salty snacks are not exactly “part of a balanced diet,” at least not on a regular basis. Add to that increasing pressures in schools and local communities to reduce or eliminate junk food marketing to chil- dren,3 and it becomes clear that a company like PepsiCo has a pretty serious public relations challenge on its hands. -

Shopping Spree Breaks Records 35.02 Billion Yuan Spent in Single’S Day Extravaganza TOP NEWS/A2

Overcast 13/15°C Reporting China and the World Since 1999 Price 2 Yuan Vol.014 No.4520 www.shanghaidaily.com Tuesday 12 November 2013 Shopping spree breaks records 35.02 billion yuan spent in Single’s Day extravaganza TOP NEWS/A2 METRO Dogs On Patrol Police dog patrols are strength- ened in Shanghai’s Zhabei District ahead of the period leading up to the Spring Festival holiday — Jan- uary 30 to February 5 next year — when there is usually an upsurge in thefts. Since dog patrols were introduced about a year ago the district has seen the number of crime cases halved. A4 NATIONAL Surveys Collide Single men in Guangdong Prov- ince are having difficulty in finding their other half because of their fast pace of life and devotion to wealth, according to a matchmak- ing website. However, a rival site says men in the province have the highest chance of success in finding a girlfriend compared to other regions. A7 WORLD Temple Ruling The UN’s top court rules that the area around an ancient temple on the Thai border belongs to Cambodia and any Thai security Typhoon survivors begging for help TOP NEWS/A3 forces there should leave. At least 28 people have been killed since Children in Cebu hold signs asking for help and food along a highway after Typhoon Haiyan brought devastation to the 2011 in disputes over owner- central Philippines, killing at least 10,000 people. The typhoon-ravaged Philippine islands face a daunting relief effort, as ship of the patch of land next to bloated bodies lay uncollected and uncounted in the streets and dazed survivors pleaded for food, water and medicine. -

Manufacturing Health: a Marriage of Convenience Between Big Food and American Consumers

MANUFACTURING HEALTH: A MARRIAGE OF CONVENIENCE BETWEEN BIG FOOD AND AMERICAN CONSUMERS PREPARED BY: LITA REYES, REYES MARKETING COMMISSIONED BY: TOMKAT CHARITABLE TRUST FEBRUARY 2012 MANUFACTURING HEALTH: A MARRIAGE OF CONVENIENCE BETWEEN BIG FOOD AND AMERICAN CONSUMERS PREPARED BY: LITA REYES, REYES MARKETING COMMISSIONED BY: TOMKAT CHARITABLE TRUST FEBRUARY 2012 To the memory of Brooks Shumway whose support emboldens me today and forward. TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ..................................................................................................................................................................5 INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................................................................................7 BIG FOOD LANDSCAPE AND HISTORY .................................................................................................................................. 9 Four Key Players for Consideration .................................................................................................................................... 9 Context Setting: Men on a Mission with Lasting Visions .................................................................................................. 9 Contemporary Priorities .....................................................................................................................................................10 CHANGING MARKETS ..................................................................................................................................................................11 -

Bell Blvd. Eyesore to Be Razed fi Nally Named Bayside Shanty Will Be Demolished for New Commercial/Residential Building City Landmark by MARK HALLUM

LARGEST AUDITED COMMUNITY NEWSPAPER • LITTLE NECK LEDGER IN QUEENS • WHITESTONE TIMES July 22–28, 2016 Your Neighborhood — Your News® FREE ALSO COVERING AUBURNDALE, COLLEGE POINT, DOUGLASTON, GLEN OAKS, FLORAL PARK LIC Pepsi sign Bell Blvd. eyesore to be razed fi nally named Bayside shanty will be demolished for new commercial/residential building city landmark BY MARK HALLUM BY BILL PARRY Bayside’s Community Board 11 picked up a notice It took nearly three de- from the city Department of cades, but the Pepsi-Cola sign Buildings which may hold in Long Island City’s Gantry welcome news for many who State Park is finally an offi- walk regularly along Bell Bou- cial New York City landmark. levard. The storefront at 42-07 The City Council voted 43-0 in Bell Blvd., which was formerly favor of the designation last home to Chelsea Coffee Shop, week. is officially slated for demoli- “For almost 90 years, the tion. swoops and swirls of the Pepsi- The building, which has Cola sign have welcomed visi- been in ruins for years, has tors to Long Island City and become an eyesore with open symbolized Queens’ status as windows, exposed brick and an industrial powerhouse,” doors torn out off the hinges. City Councilman Jimmy Van Pigeons dominate the dirty Bramer (D-Sunnyside) said. front awning and notices of “Today, after long last, we’ve rodent traps behind the steel officially made the sign a New gate suggest the existence of York City landmark, and this an interior ecosystem taken staggering piece of pop art will over by rats. -

Pepsico and Public Health: Is the Nation's Largest Food Company a Model of Corporate Responsibility Or Master of Public Relations?

City University of New York Law Review Volume 15 Issue 1 Winter 2011 Pepsico and Public Health: Is the Nation's Largest Food Company a Model of Corporate Responsibility or Master of Public Relations? Michele Simon Follow this and additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/clr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Michele Simon, Pepsico and Public Health: Is the Nation's Largest Food Company a Model of Corporate Responsibility or Master of Public Relations?, 15 CUNY L. Rev. 9 (2011). Available at: 10.31641/clr150102 The CUNY Law Review is published by the Office of Library Services at the City University of New York. For more information please contact [email protected]. PEPSICO AND PUBLIC HEALTH: IS THE NATION’S LARGEST FOOD COMPANY A MODEL OF CORPORATE RESPONSIBILITY OR MASTER OF PUBLIC RELATIONS? By Michele Simon† INTRODUCTION While most people just think of soda when they hear the name Pepsi, the multinational conglomerate called PepsiCo is actually the largest food company in the United States and second largest in the world (Nestle´ is number one).1 PepsiCo’s dizzying reach ex- tends far beyond just fizzy sodas. Formed in 1965 through a merger of Pepsi-Cola with Frito-Lay, the company’s marriage of salty snacks with soft drinks has been key to the company’s success, and sets it apart from industry competitor Coca-Cola, which still only owns beverages.2 Over the past decade, many questions have been raised about the role of the food industry in contributing to a marketing envi- ronment in which unhealthy beverages and snacks have become the norm.