From the Port of Mocha to the Eighteenth-Century Tomb of Imam Al-Mahdi Muhammad in Al-Mawahib: Locating Architectural Icons and Migratory Craftsmen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

From the Port of Mocha to the Eighteenth-Century Tomb

Binghamton University The Open Repository @ Binghamton (The ORB) Art History Faculty Scholarship Art History 2011 From the Port of Mocha to the Eighteenth-Century Tomb of Imam al-Mahdi Muhammad in al- Mawahib: Locating Architectural Icons and Migratory Craftsmen Nancy Um Binghamton University--SUNY, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://orb.binghamton.edu/art_hist_fac Part of the Architectural History and Criticism Commons, and the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Recommended Citation Nancy Um, “From the Port of Mocha to the Eighteenth-Century Tomb of Imam al-Mahdi Muhammad in al-Mawahib: Locating Architectural Icons and Migratory Craftsmen,” Proceedings of the Seminar for Arabian Studies 41 (2011): 387-400. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Art History at The Open Repository @ Binghamton (The ORB). It has been accepted for inclusion in Art History Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of The Open Repository @ Binghamton (The ORB). For more information, please contact [email protected]. PROCEEDINGS OF THE SEMINAR FOR ARABIAN STUDIES VOLUME 41 2011 Papers from the forty-fourth meeting of the Seminar for Arabian Studies held at the British Museum, London, 22 to 24 July 2010 SEMINAR FOR ARABIAN STUDIES ARCHAEOPRESS OXFORD Orders for copies of this volume of the Proceedings and of all back numbers should be sent to Archaeopress, Gordon House, 276 Banbury Road, Oxford OX2 7ED, UK. Tel/Fax +44-(0)1865-311914. e-mail [email protected] http://www.archaeopress.com For the availability of back issues see the Seminar’s web site: www.arabianseminar.org.uk Seminar for Arabian Studies c/o the Department of the Middle East, The British Museum London, WC1B 3DG, United Kingdom e-mail [email protected] The Steering Committee of the Seminar for Arabian Studies is currently made up of 13 members. -

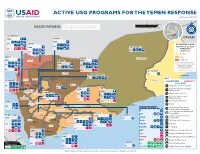

USG Yemen Complex Emergency Program

ACTIVE USG PROGRAMS FOR THE YEMEN RESPONSE Last Updated 02/12/20 0 50 100 mi INFORMA Partner activities are contingent upon access to IC TI PH O A N R U G SAUDI ARABIA conict-aected areas and security concerns. 0 50 100 150 km N O I T E G U S A A D ID F /DCHA/O AL HUDAYDAH IOM AMRAN OMAN IOM IPs SA’DAH ESTIMATED FOOD IPs SECURITY LEVELS IOM HADRAMAWT IPs THROUGH IPs MAY 2020 IPs Stressed HAJJAH Crisis SANA’A Hadramawt IOM Sa'dah AL JAWF IOM Emergency An “!” indicates that the phase IOM classification would likely be worse IPs Sa'dah IPs without current or planned IPs humanitarian assistance. IPs Source: FEWS NET Yemen IPs AL MAHRAH Outlook, 02/20 - 05/20 Al Jawf IP AMANAT AL ASIMAH Al Ghaedha IPs KEY Hajjah Amran Al Hazem AL MAHWIT Al Mahrah USAID/OFDA USAID/FFP State/PRM Marib IPs Hajjah Amran MARIB Agriculture and Food Security SHABWAH IPs IBB Camp Coordination and Camp Al Mahwit IOM IPs Sana'a Management Al Mahwit IOM DHAMAR Sana'a IPs Cash Transfers for Food Al IPs IPs Economic Recovery and Market Systems Hudaydah IPs IPs Food Voucher Program RAYMAH IPs Dhamar Health Raymah Al Mukalla IPs Shabwah Ataq Dhamar COUNTRYWIDE Humanitarian Coordination Al Bayda’ and Information Management IP Local, Regional, and International Ibb AD DALI’ Procurement TA’IZZ Al Bayda’ IOM Ibb ABYAN IOM Al BAYDA’ Logistics Support and Relief Ad Dali' OCHA Commodities IOM IOM IP Ta’izz Ad Dali’ Abyan IPs WHO Multipurpose Cash Assistance Ta’izz IPs IPs UNHAS Nutrition Lahij IPs LAHIJ Zinjubar UNICEF Protection IPs IPs WFP Ready-to-Use Therapeutic Food IOM Al-Houta ADEN FAO Refugee and Migrant Assistance IPs Aden IOM UNICEF Risk Management Policy and Practice Shelter and Settlements IPs WFP SOCOTRA DJIBOUTI, ETHIOPIA, U.S. -

The Jewish Discovery of Islam

The Jewish Discovery of Islam The Jewish Discovery of Islam S tudies in H onor of B er nar d Lewis edited by Martin Kramer The Moshe Dayan Center for Middle Eastern and African Studies Tel Aviv University T el A v iv First published in 1999 in Israel by The Moshe Dayan Cotter for Middle Eastern and African Studies Tel Aviv University Tel Aviv 69978, Israel [email protected] www.dayan.org Copyright O 1999 by Tel Aviv University ISBN 965-224-040-0 (hardback) ISBN 965-224-038-9 (paperback) All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Publication of this book has been made possible by a grant from the Lucius N. Littauer Foundation. Cover illustration: The Great Synagogue (const. 1854-59), Dohány Street, Budapest, Hungary, photograph by the late Gábor Hegyi, 1982. Beth Hatefiitsoth, Tel Aviv, courtesy of the Hegyi family. Cover design: Ruth Beth-Or Production: Elena Lesnick Printed in Israel on acid-free paper by A.R.T. Offset Services Ltd., Tel Aviv Contents Preface vii Introduction, Martin Kramer 1 1. Pedigree Remembered, Reconstructed, Invented: Benjamin Disraeli between East and West, Minna Rozen 49 2. ‘Jew’ and Jesuit at the Origins of Arabism: William Gifford Palgrave, Benjamin Braude 77 3. Arminius Vámbéry: Identities in Conflict, Jacob M. Landau 95 4. Abraham Geiger: A Nineteenth-Century Jewish Reformer on the Origins of Islam, Jacob Lassner 103 5. Ignaz Goldziher on Ernest Renan: From Orientalist Philology to the Study of Islam, Lawrence I. -

Yemen Six Month Economic Analysis Economic Warfare & The

HUMANITARIAN AND DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMME Yemen Six Month Economic Analysis Economic Warfare & the Humanitarian Context January 2017 HUMANITARIAN FORESIGHT THINK TANK HUMANITARIAN FORESIGHT THINK TANK Yemen Six Month Economic Analysis / January 2017 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY An inclusive political solution to the conflict is unlikely in the next six months, despite the high possibility of state economic collapse and a metastasizing humanitarian crisis across the country. President Hadi’s refusal to accept the terms of a recent UN peace plan is likely stalling Saudi financial relief and threatens to fracture his support base in the south. Meanwhile, the crippled state economy is supporting a thriving shadow economy, which will fragment power structures on both sides of the conflict as stakeholders engage in war profiteering. Not only will this diminish the chances for unity in the long run, it also increases food insecurity and poverty for the most vulnerable, while benefiting those in power who already dominate the parallel market. Amidst this turmoil, AQAP and IS influence will increase. This report will examine the economic context affecting humanitarian needs in Yemen, and present scenarios offering potential trajectories of the conflict to assist in humanitarian preparedness. Source: Ali Zifan (6 December 2016), Insurgency in Yemen detailed map, Wikipedia INTRODUCTION The slow progress in the war between the internationally-recognized Yemeni government of Abd Rabbu Mansour Hadi and the Zaidi Shia Houthi-Ali Abdallah Saleh alliance has caused the Saudi- backed Hadi coalition to instrumentalise the Yemeni economy, conducting a war of attrition. As Sanaa’s Central Bank of Yemen (CBY) hemorrhaged through its reserves in the previous two years of war, growing criticism of the governor’s alleged complicity in Houthi embezzlement culminated in the 18 September decision by the Hadi government to move the CBY from the Houthi-controlled capital to Aden and position a new governor to run the institution. -

Yemen Humanitarian Situation Report May 2019

UNICEF YEMEN HUMANITARIAN SITUATION REPORT MAY 2019 - Yemen Humanitarian Situation Report marginalized community during a cholera prevention session conducted femaleby religious leaders in in Al Hasabah district, Sana’a.in ©UNICEF Yemen/2019/Mona Adel. childA from a Highlights May 2019 • On 16 May, multiple air strikes hit various locations in Amanat Al Asimah and Sana’a 12.3 million governorates, killing children and wounding more than 70 civilians. Seven children # of children in need of humanitarian between the ages of 4 and 14 were also killed on 24 May in an attack on the Mawiyah assistance (estimated) district, in the southern Yemeni city of Taiz. This attack increased the verified number 24.1 million # of people in need of children killed and injured the escalation of violence near Sanaa and in Taiz to 27 in (OCHA, 2019 Yemen Humanitarian Needs only 10 days, but the actual numbers are likely to be much higher. Overview) • The number of Acute Watery Diarrhoea/suspected cholera cases has continued to rise 1.71 million since the start of 2019, with 312 out of 333 districts reporting suspected cases this year # of children internally displaced (IDPs) so far. Since 1 January 2019 to 31 May 2019, there have been 365,223 suspected cases 4.7 million and 638 associated deaths recorded (CFR 0.20 per cent). Children under five represent # of children in need of educational assistance 360,000 a quarter of the total suspected cases. # of children under 5 suffering Severe Acute • UNICEF continues to assess and monitor the nutrition situation in Yemen. -

Oman Shot the School Is Dedicated

All the News ot RED BANK and Surrounding Towns Told Fearlessly and Without BId«, Iiuued Wwkly. Entered as Eaoond-Cla<« Matter at the Poat- VOLUME LVII, NO. 18. , ofHca fit Rod Dank, N. J., under tho Act of March 8, 1878. RED BANK, N. J., WEDNESDAY, OCTOBER 24, 1934. Subscription Prlcoi Ono Year $1.50 Six Months 51.00. Slnsle Copy 4c« PAGES 1 TO 1% GOV. MOORTC AT BED BANK. KICKED BY A HORSE. Execullvo Sends Word Ho Intends Jawbone and Nose of Robert 1'lorce, to Ho Hero Friday, Night Jr., of Shrewsbury Broken. Governor A. Harry Moore and his Robert Pierce, son of Robert Mayor Augustua M. Minton Ap Democratic Opponent of Jossph stuff aro expected to attend the third General Election on November Rumson Republican Club Spon- Pierce, Jr., of Shrewsbury, is expect- McDermoit Claims That Un- annual ball and reception of tho Mid ed to return homo thla week from pointa John P. Mulvihill dletown townahlp Democrats, which 6 to be Followed by Recali soring Testimonial at Vivian necessary Expenditures Have Filkin hospital nt Asbury Park, Chairman for That Borougl Is scheduled for Friday night at tho Referendum on November 9 Johnson's—Senator Barbour where for the past two weeks ho has Been Mads. rted Bank Elks home. Tho affair was been under treatment for Injuries. —Council on Committee. placed on an annual basi3 three in Baysiioro Borough. to be Among the Speakers. Frederick F. Schock of. Spring Robert got a job on a farm nt Bail- ',\ At Monday night's meeting of th years ago and It hna been ono of the Keansburg residents will go to Many reservations have been made ey's Corner operated by William Fair Haven commissioners, Mayo Lake, Democratic candldato for coun highlights In tho campaign each suc- polls twice during the week of No ty clerk, received [in onthuslaatlc re for the testimonial dinner and danco Tansey and he was hurt on the first Headden's Corner Firemen Called Out Twice Before AuBllatua M. -

Ibb Hub 4W: Health Cluster Partners DRAFT December 2020

YEMEN Ibb Hub 4W: Health Cluster Partners DRAFT December 2020 To visit online Health Cluster Interactive 4W Saudi Arabia Click Here Oman Raymah HEALTH CLUSTER PARTNERS AND HEALTH FACILITIES Yemen 2 UN Agencies 37 Hospitals Eritrea Al Bayda 5 NNGOs 52 Health Centers Djibouti Al Qafr Yarim Somalia Dhamar 9 INGOs 29 Health Units 16 118 Ar Radmah Active Health Al Qafr Hazm Al Udayn As Saddah Partners Facilities Al Makhadir Hubaysh Number of Health Partner provinding Health Services Al Hudaydah Partner Mental An Nadirah Medical Reproductive Child H Capacity Medical Pharmac Operationa Ibb organization by NCD Health Ash Sha'ir Consultations Health Services Building Support euticals l Support Ibb Governorate Services Ba'dan Ibb Al Dhihar Al Udayn BFD l l l Far Al Udayn Al Mashannah Jiblah INTERSOS l l l l l l l l Mudhaykhirah MSI l l Mudhaykhirah As Sabrah Al Dhale'e As Sayyani MdM l l l l l l l l Dhi As Sufal Shara'b As Salam UNFPA l l Shara'b Ar Rawnah WHO l l l l YFCA l At Ta'iziyah Selah l l Maqbanah Taizz Al Qahirah Taizz Al Mudhaffar Mawiyah l l l l Salh ADD Sabir Al Mawadim BFD l l l Sabir Al Mawadim Al Misrakh Al Mukha Human Access l Mawza Jabal Habashy DEEM l l l l l l l Al Misrakh Dimnat Khadir FHI360 l l l l l Sama HI l As Silw Al Ma'afer MSI l l Al Mawasit PU-AMI l l l l l l l Hayfan QRCS l l l l l l l SCI l l l l l l l l Ash Shamayatayn UNFPA l l Al Wazi'iyah WHO l l l l Selah l l Dhubab Lahj Partners per District ≥ 6 Aden 5 Eritrea 0 10 20 KM 4 3 Djibouti 2 1 Product Name: Health Cluster Partners per Governorate December 2020 Disclaimer: The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations. -

Oxford University Theology & Religion Faculty Magazine

THE OXFORD THEOLOGIAN OXFORD UNIVERSITY THEOLOGY & RELIGION FACULTY MAGAZINE ISSUE 7 . SUMMER 2018 OXFORD UNIVERSITY THEOLOGY THE OXFORD & RELIGION FACULTY MAGAZINE THEOLOGIAN ISSUE 7 . SUMMER 2018 CONTENTS A MESSAGE FROM THE FACULTY BOARD CHAIR 1 Graham Ward THE INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON PATRISTICS STUDIES 2 An interview with CAROL HARRISON and MARK EDWARDS MEET OUR EARLY CAREER RESEARCHERS 6 Ann Giletti, Alex Henley, Michael Oliver, Cressida Ryan and Bethany Sollereder NEW GENERATION THINKER 11 An interview with DAFYDD MILLS DANIEL Managing editor: Phil Booth SHARI‘A COURTS: Exploring Law and Ethics in 13 Deputy Managing Editor: Michael Oliver Contemporary Islam Deputy editors: Marek Sullivan Justin Jones Design and production: Andrew Esson, SCIENCE, THEOLOGY, & HUMANE PHILOSOPHY: Central and 14 Baseline Arts Eastern European Perspectives Profound thanks to: All the staff in the Faculty Andrew Pinsent Office THE PHILOSOPHY OF THE GREEK CHURCH FATHERS 16 Johannes Zachhuber STAY IN TOUCH! We are always eager to hear from you! Please UNDERGRADUATE PRIZES 19 keep in touch with the Faculty at general. [email protected]. If you have news items for the Alumni News section in FACULTY NEWS 20 future issues of the Theologian, you can let us know about them on our dedicated email address, [email protected]. We WORKSHOPS & PROJECTS 22 also recommend that all alumni consider opening an online account with the University COMINGS AND GOINGS 24 of Oxford Alumni Office: www.alumni.ox.ac.uk. KEEP UP WITH THE FACULTY ONLINE! FACULTY BOOKS 26 www.facebook.com/oxfordtheologyfaculty/ www.theology.ox.ac.uk OXFORD THEOLOGICAL MONOGRAPHS 2017–18 32 www.instagram.com/faculty_theology_ religion/ FROM THE FACULTY BOARD CHAIR GRAHAM WARD Mid July, and the academic year finally arrives at the summer Dr Alex Henley will be working on ‘A Genealogy of Islamic Religious hiatus in weeks of hot, dry weather. -

Justice in Transition in Yemen a Mapping of Local Justice Functioning in Ten Governorates

[PEACEW RKS [ JUSTICE IN TRANSITION IN YEMEN A MAPPING OF LOCAL JUSTICE FUNCTIONING IN TEN GOVERNORATES Erica Gaston with Nadwa al-Dawsari ABOUT THE REPORT This research is part of a three-year United States Institute of Peace (USIP) project that explores how Yemen’s rule of law and local justice and security issues have been affected in the post-Arab Spring transition period. A complement to other analytical and thematic pieces, this large-scale mapping provides data on factors influencing justice provision in half of Yemen’s governorates. Its goal is to support more responsive programming and justice sector reform. Field research was managed by Partners- Yemen, an affiliate of Partners for Democratic Change. ABOUT THE AUTHORS Erica Gaston is a human rights lawyer at USIP special- izing in human rights and justice issues in conflict and postconflict environments. Nadwa al-Dawsari is an expert in Yemeni tribal conflicts and civil society development with Partners for Democratic Change. Cover photo: Citizens observe an implementation case proceeding in a Sanaa city primary court. Photo by Erica Gaston. The views expressed in this report are those of the authors alone. They do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Institute of Peace. United States Institute of Peace 2301 Constitution Ave., NW Washington, DC 20037 Phone: 202.457.1700 Fax: 202.429.6063 E-mail: [email protected] Web: www.usip.org Peaceworks No. 99. First published 2014. ISBN: 978-1-60127-230-0 © 2014 by the United States Institute of Peace CONTENTS PEACEWORKS • SEPTEMBER 2014 • NO. 99 [The overall political .. -

Politics, Governance, and Reconstruction in Yemen January 2018 Contents

POMEPS STUDIES 29 Politics, Governance, and Reconstruction in Yemen January 2018 Contents Introduction . .. 3 Collapse of the Houthi-Saleh alliance and the future of Yemen’s war . 9 April Longley Alley, International Crisis Group In Yemen, 2018 looks like it will be another grim year . 15 Peter Salisbury, Chatham House Middle East and North Africa Programme Popular revolution advances towards state building in Southern Yemen . 17 Susanne Dahlgren, University of Tampere/National University of Singapore Sunni Islamist dynamics in context of war: What happened to al-Islah and the Salafis? . 23 Laurent Bonnefoy, Sciences Po/CERI Impact of the Yemen war on militant jihad . 27 Elisabeth Kendall, Pembroke College, University of Oxford Endgames for Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates in Yemen . 31 Kristian Coates Ulrichsen, Rice University’s Baker Institute for Public Policy Yemen’s war as seen from the local level . 34 Marie-Christine Heinze, Center for Applied Research in Partnership with the Orient (CARPO) and Hafez Albukari, Yemen Polling Center (YPC) Yemen’s education system at a tipping point: Youth between their future and present survival . 39 Mareike Transfeld, Freie Universität Berlin, Berlin Graduate School of Muslim Cultures and Societies Gasping for hope: Yemeni youth struggle for their future . 43 Ala Qasem, Resonate! Yemen Supporting and failing Yemen’s transition: Critical perspectives on development agencies . 46 Ala’a Jarban, Concordia University The rise and fall and necessity of Yemen’s youth movements . 51 Silvana Toska, Davidson College A diaspora denied: Impediments to Yemeni mobilization for relief and reconstruction at home . 55 Dana M. Moss, University of Pittsburgh War and De-Development . -

History of the Big Spring Presbyterian Church, Newville, Pa. : 1737-1898

'>'<'"*'?,'' .".la ki&h 2— >> FHill SWOPE. "• • n c. ttit ®h(o%,v«| ^^ M!^^% ^^ttin PRINCETON, N. J. Purchased by the Mi's. Robert Lenox Kennedy Church History Fund. BX 9211 .N628 S86 1898 ''^^''^" Ernest, ^891: i860) History of the Big Spring Gilbert E. Swope, HISTORY OF THE Big Spiiiig PiesHylenaD CH NEWVILLE, PA. •737== '898. BY (Silbevt Ernest Swope, Author of '*A History of the S'wopc Family/' With an Introduction by REV. EBENEZER ERSKINE, D. D. NEWVILLE. PA., TIMES STEAM PRINTING HOUSE: 1898. II PREFACE. In presenting this little liistory of the Big Spring Presbyte- rian Church, we feel quite safe in saying that we are giving all that is obtainable regarding the congregation, and more than we expected to find when we began our work. Owing to the fact that there were no records in possession of the congregation prior to 1830 except an old trustees minute book, the prospect for ob- taining data was not very encouraging. However, by careful inquiry among the old families of the church and other means, we were enabled to find that herein given. Through the kind- ness of Miss Jennie W. Davidson, a great granddaughter of Rev. Samuel Wilson, we were given permission to examine a great mass of old family papers, the accumulation of more than a cen- tury. Among these papers we were fortunate enough to find much valuable matter, relating not only to the ministry of Rev. Samuel Wilson but also to that of some of his predecessors. No regular session books seem to have been kept by the early pas- tors, all the records found being on detached pieces of paper. -

Representations of Muslims and Islam in US Mainstream Media

Marquette University e-Publications@Marquette Ronald E. McNair Scholars Program 2013 Ronald E. McNair Scholars Program 7-1-2013 Andrew I. Thompson - From Tragedy to Policy: Representations of Muslims and Islam in U.S. Mainstream Media Andrew I. Thompson Marquette University Follow this and additional works at: http://epublications.marquette.edu/mcnair_2013 Part of the Mass Communication Commons, and the Other Race, Ethnicity and post-Colonial Studies Commons Recommended Citation Thompson, Andrew I., "Andrew I. Thompson - From Tragedy to Policy: Representations of Muslims and Islam in U.S. Mainstream Media" (2013). Ronald E. McNair Scholars Program 2013. Book 14. http://epublications.marquette.edu/mcnair_2013/14 From Tragedy to Policy: Representations of Muslims and Islam in U.S. Mainstream Media Andrew Thompson Faculty Mentors: Dr. Grant Silva & Dr. Risa Brooks Departments of Political Science & Philosophy Ronald E. McNair Scholars Program Summer 2013 & Honors Program Thompson 1 As the world becomes more globalized, the tangible lines dividing countries and cultures are increasingly blurred. The inter-connectedness of the globe brings people thousands of miles away from each other together in a matter of seconds. However, as globalization has proliferated, other theories of dividing the world have arisen. One of the most popular—some may argue it is the most popular—theories of dividing up the world was published in 1993 in Foreign Affairs by Samuel Huntington. Originally titled “Clash of Civilizations?”—later on the question mark was removed when the thesis was expounded upon and made into a book—Huntington attempted to provide readers with a new term that described a long-standing, internalized political myth: “The idea of a Clash between Civilizations is a sort of electric spark that sets people’s imagination alight, because it finds fertile soil in which to proliferate” (Bottici & Challand, 2010, p.