Fteval JOURNAL for Research and Technology Policy Evaluation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PIK-Sachbericht 2019

Inhaltsverzeichnis 01 Highlights 02 Eckdaten 03 Forschungsabteilungen 04 FutureLabs Wissenschaftsunterstützende 05 Organisationseinheiten 06 Anhang 7 United in Science 9 Von Deutschland nach Europa und in die Welt 12 Aus der Forschung 18 In eigener Sache 23 Wissenschaftliche Politikberatung 26 Medien-Highlights 2019 28 Besuche am PIK 29 Wissenschaftliche Politikberatung 30 Breitenwirkung 33 Klima, Kunst und Kultur 34 Berlin-Brandenburg – das PIK aktiv in der Heimat 36 Finanzierung | Beschäftigungszahlen 37 Publikationen | PIK in den Medien 38 Vorträge, Lehre und Veranstaltungen | Wissenschaftlicher Nachwuchs 40 Forschungsabteilung 1 – Erdsystemanalyse 46 Forschungsabteilung 2 – Klimaresilienz 52 Forschungsabteilung 3 – Transformationspfade 58 Forschungsabteilung 4 – Komplexitätsforschung 64 69 Informationstechnische Dienste 70 Verwaltung 71 Kommunikation 72 Stab der Direktoren 73 Wissenschaftsmanagement und Transfer 75 Organigramm 76 Kuratorium und Wissenschaftlicher Beirat 77 Auszeichnungen und Ernennungen 80 Berufungen, Habilitationen und Stipendien 81 Drittmittelprojekte 89 Veröff entlichungen 2019 5 Vorwort So klar man schon jetzt sagen kann, dass 2020 als Aber wir haben noch viel vor uns, das zeigt auch die das Corona-Jahr in die Geschichte eingehen wird, Pandemie-Krise, während derer dieser PIK-Sachbe- so klar lässt sich wohl auch sagen: 2019 war ein richt erstellt wurde. Die Herausforderungen werden Klima-Jahr. Klar wie nie zuvor standen Klimawandel komplexer und internationaler. Von den Planetaren und Klimapolitik im Mittelpunkt der öffentlichen Grenzen bis zu den Globalen Gemeinschaftsgütern: Aufmerksamkeit. Angestoßen durch die Fridays for Nachhaltiger Wohlstand im 21. Jahrhundert und da- Future-Bewegung gingen in Deutschland und überall rüber hinaus hängt ab vom grenzüberschreitenden auf der Welt Hunderttausende junge Menschen auf Management öff entlicher Güter – das gilt für den Ge- die Straße – unter Berufung auf die Klimaforschung, sundheitsschutz genauso wie für die Klimastabilität. -

Research Library Page 1

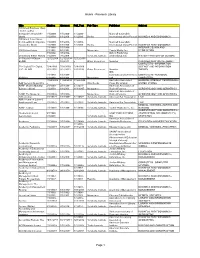

Alumni - Research Library Title Citation Abstract Full_Text Pub Type Publisher Subject 100 Great Business Ideas : from Leading Companies Around the 1/1/2009- 1/1/2009- 1/1/2009- Marshall Cavendish World 1/1/2009 1/1/2009 1/1/2009 Books International (Asia) Pte Ltd BUSINESS AND ECONOMICS 100 Great Sales Ideas : from Leading Companies 1/1/2009- 1/1/2009- 1/1/2009- Marshall Cavendish Around the World 1/1/2009 1/1/2009 1/1/2009 Books International (Asia) Pte Ltd BUSINESS AND ECONOMICS 1/1/1988- 1/1/1988- INTERIOR DESIGN AND 1001 Home Ideas 6/1/1991 6/1/1991 Magazines Family Media, Inc. DECORATION 3/1/2002- 3/1/2002- Oxford Publishing 20 Century British History 7/1/2009 7/1/2009 Scholarly Journals Limited(England) HISTORY--HISTORY OF EUROPE 33 Charts [33 Charts - 12/12/2009 12/12/2009- 12/12/2009 BLOG] + 6/3/2011 + Other Resources Newstex CHILDREN AND YOUTH--ABOUT COMPUTERS--INFORMATION 50+ Digital [50+ Digital, 7/28/2009- 7/28/2009- 7/28/2009- SCIENCE AND INFORMATION LLC - BLOG] 2/22/2010 2/22/2010 2/22/2010 Other Resources Newstex THEORY IDG 1/1/1988- 1/1/1988- Communications/Peterboro COMPUTERS--PERSONAL 80 Micro 6/1/1988 6/1/1988 Magazines ugh COMPUTERS 11/24/2004 11/24/2004 11/24/2004 Australian Associated GENERAL INTEREST PERIODICALS-- AAP General News Wire + + + Wire Feeds Press Pty Limited UNITED STATES AARP Modern Maturity; 2/1/1988- 2/1/1988- 2/1/1991- American Association of [Library edition] 1/1/2003 1/1/2003 11/1/1997 Magazines Retired Persons GERONTOLOGY AND GERIATRICS American Association of AARP The Magazine 3/1/2003+ 3/1/2003+ Magazines Retired Persons GERONTOLOGY AND GERIATRICS ABA Journal 8/1/1972+ 1/1/1988+ 1/1/1992+ Scholarly Journals American Bar Association LAW ABA Journal of Labor & Employment Law 7/1/2007+ 7/1/2007+ 7/1/2007+ Scholarly Journals American Bar Association LAW MEDICAL SCIENCES--NURSES AND ABNF Journal 1/1/1999+ 1/1/1999+ 1/1/1999+ Scholarly Journals Tucker Publications, Inc. -

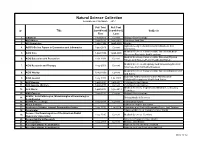

Natural Science Collection Accurate As of 06 March 2017

Natural Science Collection Accurate as of 06 March 2017 Full Text Full Text Lp Title (combined) (combined) Subjects First Last 1. 3 Biotech 1-kwi-2012 Current Biology--Biotechnology 2. A&D Watch 1-sty-2013 1-gru-2015 Petroleum And Gas 3. AEI Newsletter 1-cze-1998 1-paź-2000 Energy Agriculture--Agricultural Economics|Business And 4. AGRIS On-line Papers in Economics and Informatics 1-gru-2010 Current Economics Medical Sciences--Communicable Diseases|Medical 5. AIDS Care 1-paź-1996 1-paź-2000 Sciences--Psychiatry And Neurology Medical Sciences--Communicable Diseases|Physical 6. AIDS Education and Prevention 1-sie-1998 Current Fitness And Hygiene|Public Health And Safety Medical Sciences--Allergology And Immunology|Medical 7. AIDS Research and Therapy 1-sty-2009 Current Sciences--Communicable Diseases Medical Sciences--Communicable Diseases|Public Health 8. AIDS Weekly 13-lut-1995 Current And Safety Business And Economics--Labor And Industrial 9. AIHA Journal 1-sty-1993 1-lis-2003 Relations|Occupational Health And Safety 10. AKC Gazette 1-paź-2001 1-wrz-2011 Pets|Sports And Games 11. AKC Gazette (Online) 1-paź-2011 Current Pets|Sports And Games Medical Sciences--Experimental Medicine, Laboratory 12. ALN World 1-paź-2013 1-gru-2014 Technique 13. AMB Express 1-sty-2012 Current Biology--Biotechnology APMIS ; Acta Pathologica, Microbiologica et Immunologica 14. Biology|Medical Sciences Scandinavica 15. ASTRA Proceedings 1-sty-2014 Current Astronomy|Physics 16. About Campus Education--Higher Education 17. Academica Science Journal, Geographica Series 1-sty-2012 1-lip-2014 Environmental Studies|Geography|Travel And Tourism 18. Accelerator Education|Sciences: Comprehensive Works Access : the Newsmagazine of the American Dental 19. -

The Role of the Transcription Factor SOX2 in Tumorigenesis and Development of the Stomach

Dissertation zur Erlangung des Doktorgrades der Naturwissenschaften der Fakultät für Biologie der Ludwig-Maximilians- Universität München The role of the transcription factor SOX2 in tumorigenesis and development of the stomach Vorgelegt von Katharina Antonia Hütz München 2013 2 „Wenn Du ein Schiff bauen willst, dann trommle nicht Männer zusammen um Holz zu beschaffen, Aufgaben zu vergeben und die Arbeit einzuteilen, sondern lehre die Männer die Sehnsucht nach dem weiten, endlosen Meer.“ Antoine de Saint-Exupery 3 4 Erklärung Diese Dissertation wurde im Sinne von § 13 Abs. 3 bzw. 4 der Promotionsordnung vom 29. Januar 1998 (in der Fassung der sechsten Änderungssatzung vom 16. August 2010) von Prof. Thomas Cremer von der Fakultät der Biologie vertreten. Eidesstattliche Versicherung Diese Dissertation wurde selbständig, ohne unerlaubte Hilfe erarbeitet. München, ……………………………………………………. Katharina Hütz Dissertation eingereicht am 06. Juni 2013 1. Gutachter: Prof. Thomas Cremer 2. Gutachter: Prof. Elisabeth Weiss Mündliche Prüfung am 21. Oktober 2013 5 6 Meinen Eltern und meinen Schwestern 7 8 Table of Contents Table of Contents ................................................................................................................. 9 List of Abbreviations .......................................................................................................... 13 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................ 17 1.1. The stomach ..................................................................................................... -

David Dunning 1 VITA

David Dunning 1 VITA DAVID DUNNING June 13, 2019 CONTACT INFORMATION Department of Psychology University of Michigan East Hall 530 Church St. Ann Arbor, MI 14809 734/763-0063 734/764-3520 (fax) email: [email protected] Web: http://cornellpsych.org/sasi/index.php EDUCATION Ph.D., Psychology, Stanford University, Stanford, California, 1986 B.A., Psychology, Michigan State University, East Lansing, 1982 PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE University of Michigan Professor, 2015-present Faculty Affiliate, Research Center for Group Dynamics, Institute for Social Research, 2015-present Cornell University Professor Emeritus, 2015-present Professor, 1999-2015 Associate Professor, 1992-1998 Assistant Professor, 1986-1992 Visiting Appointments Visiting Fellow, University of Michigan, January-June 2000 Whitebox Fellow in Behavioral Finance, Yale University School of Management, August 2004. Visiting Scholar, SonderForschungsBereich 504 [Collaborative Research Center 504], University of Mannheim, Germany, June 2005. Visiting Instructor, Instituts für Wirtschafts und Sozialpsychologie [Institute for Economics and Social Psychology], University of Cologne, Germany, July 2008, June 2009, September 2010, July 2015. Invited Fellow, Center for the Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences, Stanford, CA, 2013-2014. David Dunning 2 OUTSIDE PROFESSIONAL ACTIVITIES Fellow, American Psychological Association Member, Early Career Award Committee (Social Psychology), 2002 Member, Publication & Communication Board, 2011-2017 (Chair, 2013-2014) Member, Electronic Resource Advisory Committee, 2011-2012, 2016-2017 Member, Journal Advisory Committee, 2012-2016 Co-Chair, Editorial Search Committee, Decision, 2012 Chair, Editorial Search Committee, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology: Interpersonal Relations and Group Processes, 2013 Chair, Editorial Search Committee, History of Psychology, 2014. Co-Chair, Editorial Search Committee, International Perspectives in Psychology, 2015. Member, Editorial Search Committee, Health Psychology, 2015. -

Sunday Evening News January – Januar 2018 Selected and Edited by BGF Jany ______Woche 01 – Week 01 (01.01

Sunday Evening News January – Januar 2018 Selected and edited by BGF Jany ____________________________________________________________________________ Woche 01 – Week 01 (01.01. – 07.01.2018) Press releases - Media Gibney E. - Nature What to expect in 2018: science in the new year Moon missions, ancient genomes and a publishing showdown are set to shape research. https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-018-00009-5 Evolution News Peer-Reviewed Science: A “Mathematical Proof of Darwinian Evolution” Is Falsified https://evolutionnews.org/2018/01/peer-reviewed-science-a-mathematical-proof-of-darwinian-evolution-is- falsified/ Tarek Abd El-Galil | Al-Fanar Media Egypt develops high-yield arid-resistant GMO wheat but activist opposition blocks biotechnology advances https://geneticliteracyproject.org/2018/01/04/egypt-develops-high-yield-arid-resistant-gmo-wheat-activist- opposition-blocks-biotechnology-advances/ In Egypt, Genetic Crop Modification Is On Hold https://www.al-fanarmedia.org/2017/12/egypt-genetic-crop-modification-hold/#.Wjqm-5GWCvw.twitter Letters to the Editor: Opinion – Washington Post Is GMO opposition immoral? https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/is-gmo-opposition-immoral/2018/01/01/2c9e6a54-ecc3-11e7- 956e-baea358f9725_story.html Letters in respect to: Daniels M: Avoiding GMOs isn’t just anti-science. It’s immoral. https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/avoiding-gmos-isnt-just-anti-science-its- immoral/2017/12/27/fc773022-ea83-11e7-b698-91d4e35920a3_story.html?utm_term=.f141cd16a9d7 ____________________________________ Genome Editing – New Techniques KWS: Genome Editing Die neuen Züchtungsmethoden ergänzen den Werkzeugkasten der Pflanzenzüchter und bieten zusätzliche Möglichkeiten, Pflanzen züchterisch gezielt zu verbessern. Die Folgen des Klimawandels, neue Schadpilze, der Wunsch nach weniger Dünger auf dem Acker und einer hohen Qualität landwirtschaftlicher Produkte: Auf alle diese Herausforderungen an eine nachhaltige Landwirtschaft reagieren Pflanzenzüchter mit neuen Sorten und nutzen dafür die jeweils am besten geeigneten Züchtungsmethoden. -

Bericht 2015

WZB Wissenschaftszentrum Berlin für Sozialforschung Bericht 2015 WZB Wissenschaftszentrum Berlin für Sozialforschung Bericht 2015 Impressum WZB Aufgaben und Arbeiten Bericht 2015 ISSN 0935-574 X WZB-Mitteilungen Im Wissenschaftszentrum Berlin für Sozialforschung (WZB) betreiben rund Redaktion ISSN 01743120 Heidi160 Hilzingerdeutsche (geschäftsführend) und ausländische Wissenschaftler problemorientierte Grund Gabrielelagenforschung. Kammerer Soziologen, Politologen, Ökonomen, Rechtswissenschaftler Heft 136, Juni 2012 Kerstin Schneider Dr.und Paul Historiker Stoop erforschen Entwicklungstendenzen, Anpassungsprobleme und Herausgeberin Innovations chancen moderner Gesellschaften. Gefragt wird vor allem nach Die Präsidentin des Wissenschaftszentrums Korrektoratden Problemlösungskapazitäten gesellschaftlicher und staatlicher Institutionen. Berlin für Sozialforschung Martina Sander-Blanck Professorin Jutta Allmendinger Ph.D. Von besonderem Gewicht sind Fragen der Transnationalisierung und Globali Dokumentationsierung. Die Forschungsfelder des WZB sind: 10785 Berlin Udo Borchert, Torben Heinze, Christin Wendlandt Mitarbeit: Barbara Schlüter Reichpietschufer 50 – Arbeit und Arbeitsmarkt Herausgeberin Telefon 03025 4910 Die– Bildung Präsidentin und des WissenschaftszentrumsAusbildung Berlin Telefax 03025 49 16 84 für– Sozialstaat Sozialforschung und gGmbH soziale Ungleichheit Prof.– Geschlecht Jutta Allmendinger und FamiliePh.D. Internet: www.wzb.eu 10785– Industrielle Berlin, Reichpietschufer Beziehungen 50 und Globalisierung Die WZBMitteilungen -

Der Berliner Pressemarkt

Der Berliner Pressemarkt Historische, ökonomische und international vergleichende Marktanalyse und ihre medienpolitischen Implikationen Prof. Dr. Stephan Weichert und Leif Kramp unter Mitarbeit von Alexander Matschke Berlin, Januar 2009 1 Inhaltsverzeichnis 1. Einleitung: „Katerstimmung“ auf dem Regionalzeitungsmarkt 4 2. Historische Entwicklung des Berliner Tageszeitungsmarktes 7 3. Analyse der ökonomischen Struktur 21 4. Internationaler Vergleich 68 5. Schlussfolgerungen und medienpolitische Handlungsempfehlungen 90 6. Referenzen 94 Abbildungsverzeichnis Abb. 1: Marktanteile einzelner Pressetitel im Verkauf (montags bis freitags) im Berliner Verbreitungsgebiet 21 Abb. 2: Verkaufte Auflage Berliner Tageszeitungen (montags bis freitags) von 1998 bis 2008 22 Abb. 3: Verkaufte Auflage überregionaler Zeitungen (montags bis freitags) im Berliner Verbreitungsraum im jeweils 1. Quartal 1998 bis 23 2008 Abb. 4: Verkaufte tägliche Auflage Berliner Tageszeitungen (montags bis freitags) anteilig innerhalb und außerhalb des Berliner 24 Verbreitungsgebietes Abb. 5: Anzahl der festangestellten Journalisten in Berlin nach Medienunternehmen in 2008 26 Abb. 6: Organigramm: Beteiligungen der Axel Springer AG an Presseerzeugnissen (National) 39 Abb. 7: Tageszeitungen im Axel Springer Verlag 40 Abb. 8: Organigramm: Beteiligungen der Axel Springer AG an Online-Publikationen 44 Abb. 9: Organigramm: Beteiligungen der Georg von Holtzbrinck GmbH an Verlagen 52 Abb. 10a: Organigramm: Beteiligungen der Georg von Holtzbrinck GmbH an Presseerzeugnissen 53 Abb. 10b: Organigramm: Beteiligungen der Georg von Holtzbrinck GmbH an Presseerzeugnissen (Fortsetzung) 54 Abb. 11a: Organigramm: Beteiligungen der Georg von Holtzbrinck GmbH an Online-Angeboten – Teil 1 57 Abb. 11b: Organigramm: Beteiligungen der Georg von Holtzbrinck GmbH an Online-Angeboten – Teil 2 58 Abb. 12: Organigramm: Unternehmensstruktur der BVZ Deutsche Mediengruppe 65 Abb. 13: Auflage von „Le Monde“ in den Jahren 2004 bis 2007 81 Abb. -

On the Absolute Magnitude of the Special Theory of Relativity

G. O. Mueller On the Absolute Magnitude of the Special Theory of Relativity Text Version 1.2 - 2004 Supplement, May 2009: Chapter 9 The Thought Experiment English Translation: Rothwell Bronrowan November 2012 Chapter 9: The Thought Experiment Copyright of the English Translation 2012 Ekkehard Friebe The original German publication of 2009: G. O. Mueller Über die absolute Größe der Speziellen Relativitätstheorie Textversion 1.2 - 2004 Ergänzung 2009: Kapitel 9 : Das Gedankenexperiment 263 pp. Download of the complete book (chapter 1-9) available under: http://www.ekkehard-friebe.de/buch.pdf G. O. Mueller: STR II 2012 Chapter 9: The Thought Experiment The Research Project of G. O. Mueller: 95 Jahre Kritik der Speziellen Relativitätstheorie (1908-2003) [95 Years of Criticism of the Special Theory of Relativity] Representatives of the Research Project: Mr. Ekkehard Friebe (Munich) Homepage: http://www.ekkehard-friebe.de - Email: [email protected] Ms. Jocelyne Lopez Homepage: http://www.jocelyne-lopez.de - Email: [email protected] Website: Kritische Stimmen zur Relativitätstheorie [Voices critical of the Relativity Theory] http://www.kritik-relativitaetstheorie.de The Documentation: Über die absolute Größe der Speziellen Relativitätstheorie [On the Absolute Magnitude of the Special Theory of Relativity] Kapitel 1-9 [Chapter 1-9] Text Version 1.2 - 2004-2009 Publications in English: 95 Years of Criticism of the Special Theory of Relativity The G. O. Mueller Research Project. Description of a German Research Project of international scope. May 2006. - 51 pp. First Open Letter about the Freedom of Science to some 290 public figures, personalities, newspapers, and journals in Europe and the USA.