DOJ Report – Outaouais Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FICHE TECHNIQUE RÉGION OUTAOUAIS, Laurentides, ABITIBI-TÉMISCAMINGUE ET SAGUENAY LAC-ST-JEAN

FICHE TECHNIQUE RÉGION OUTAOUAIS, lAURENTIDES, ABITIBI-TÉMISCAMINGUE ET SAGUENAY LAC-ST-JEAN 4 MARS 2021 – Tournée sur la gestion de l’offre. Outaouais, Laurentides, Abitibi-Témiscamingue et Saguenay-Lac-Saint- Jean La Les Collines- Vallée- OUTAOUAIS Canada Québec Outaouais Papineau Gatineau de- Pontiac de-la- l'Outaouais Gatineau Nombre de fermes (en 2016) TOTAL 193 492 28 919 1 055 256 79 276 169 275 Élevage de bovins laitiers et production laitière 10 525 5 163 72 26 1 8 12 25 Élevage de volailles et production d'œufs 4 903 875 9 5 0 3 0 1 TOTAL des fermes sous gestion de l’offre 15 428 6 038 81 31 1 11 12 26 7,6 % Les Deux- Thérèse- La Pays Les Québe Laurentide Mont De Mirabe Rivière Argenteui Antoine LAURENTIDES Canada - Laurentide c s - Blainvill l -du- l -Labelle d'en- s agnes e Nord Haut Nombre de fermes (en 2016) 193 TOTAL 492 28 919 1 337 262 79 362 69 186 19 118 242 Élevage de bovins laitiers et production laitière 10 525 5 163 171 18 8 62 5 37 0 7 34 Élevage de volailles et production d'œufs 4 903 875 22 6 0 4 5 2 1 0 4 TOTAL des fermes sous gestion de l’offre 15 428 6 038 193 24 8 66 10 39 1 8 38 14,4 % Nord- Abitibi- Témis- Rouyn- Abitibi- La Vallée- ABITIBI-TÉMISCAMINGUE Canada Québec Abitibi du- Témiscamingue camingue Noranda Ouest de-l’Or Québec Nombre de fermes (en 2016) TOTAL 193 492 28 919 580 219 48 145 134 28 6 Élevage de bovins laitiers et production laitière 10 525 5 163 102 51 1 21 24 5 0 Élevage de volailles et production d’œufs 4 903 875 5 1 0 0 1 3 0 TOTAL des fermes sous gestion de l’offre 15 428 6 038 107 -

Growth Responses of Riparian Thuja Occidentalis to the Damming of a Large Boreal Lake

53 Growth responses of riparian Thuja occidentalis to the damming of a large boreal lake Bernhard Denneler, Yves Bergeron, Yves Be´ gin, and Hugo Asselin Abstract: Growth responses of riparian eastern white cedar trees (Thuja occidentalis L.) to the double damming of a large lake in the southeastern Canadian boreal forest was analyzed to determine whether the shoreline tree limit is the result of physiological flood stress or mechanical disturbances. The first damming, in 1915, caused a rise in water level of ca. 1.2 m and resulted in the death of the trees that formed the ancient shoreline forest, as well as the wounding and tilting of the surviving trees (by wave action and ice push) that constitute the present forest margin. The second damming, in 1922, did not further affect the water level, but did retard the occurrence of spring high water levels, as well as reduce their magnitude. However, this did not injure or affect the mortality of riparian eastern white cedars. Radial growth was not affected by flooding stress, probably because inundation occurred prior to the start of the growing season (1915–1921) or was of too short duration to adversely affect tree metabolism (after 1921). It follows that (i) the shoreline limit of east- ern white cedar is a mechanical rather than a physiological limit, and (ii) disturbance-related growth responses (e.g., ice scars, partial cambium dieback, and compression wood) are better parameters than ring width for the reconstruction of long-term water level increases of natural, unregulated lakes. Key words: compression wood, eastern white cedar, flooding, ice scars, mortality, partial cambium dieback. -

Dispossessing the Algonquins of South- Eastern Ontario of Their Lands

"LAND OF WHICH THE SAVAGES STOOD IN NO PARTICULAR NEED" : DISPOSSESSING THE ALGONQUINS OF SOUTH- EASTERN ONTARIO OF THEIR LANDS, 1760-1930 MARIEE. HUITEMA A thesis submitted to the Department of Geography in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Queen's University Kingston, Ontario, Canada 2000 copyright O Maqke E. Huiterna, 0 11 200 1 Nationai Library 6iblioîMque nationale du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographie Senrices services bibliographiques The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive permettant à la National Library of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or sell reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in microform, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfiche/nlm, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format electronique. The author retaias ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in tbis thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts fiom it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels rnay be printed or othexwise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. ABSTRACT Contemporary thought and current üterature have estabüshed links between unethical colonial appropriation of Native lands and the seemingly unproblematic dispossession of Native people from those lands. The principles of justification utiiized by the colonking powers were condoned by the belief that they were commandeci by God to subdue the earth and had a mandate to conquer the wildemess. -

Montreal, Québec

st BOOK BY BOOK BY DECEMBER 31 DECEMBER 31st AND SAVE $200 PER COUPLE AND SAVE $200 PER COUPLE RESERVATION FORM: (Please Print) TOUR CODE: 18NAL0629/UArizona Enclosed is my deposit for $ ______________ ($500 per person) to hold __________ place(s) on the Montreal Jazz Fest Excursion departing on June 29, 2018. Cost is $2,595 per person, based on double occupancy. (Currently, subject to change) Final payment due date is March 26, 2018. All final payments are required to be made by check or money order only. I would like to charge my deposit to my credit card: oMasterCard oVisa oDiscover oAmerican Express Name on Card _____________________________________________________________________________ Card Number ______________________________________________ EXP_______________CVN_________ NAME (as it appears on passport): o Mr. o Mrs. o Ms.______________________________________ Date of Birth (M/D/Y) _______/_______/________ NAME (as it appears on passport): o Mr. o Mrs. o Ms.______________________________________ Date of Birth (M/D/Y) _______/_______/________ NAME FOR NAME BADGE IF DIFFERENT FROM ABOVE: 1)____________________________________ 2)_____________________________________ STREET ADDRESS: ____________________________________________________________________ CITY:_______________________________________STATE:_____________ZIP:___________________ PHONE NUMBERS: HOME: ( )______________________ OFFICE: ( )_____________________ 1111 N. Cherry Avenue AZ 85721 Tucson, PHOTO CREDITS: Classic Escapes; © Festival International de Jazz de Montréal; -

River Ice Management in North America

RIVER ICE MANAGEMENT IN NORTH AMERICA REPORT 2015:202 HYDRO POWER River ice management in North America MARCEL PAUL RAYMOND ENERGIE SYLVAIN ROBERT ISBN 978-91-7673-202-1 | © 2015 ENERGIFORSK Energiforsk AB | Phone: 08-677 25 30 | E-mail: [email protected] | www.energiforsk.se RIVER ICE MANAGEMENT IN NORTH AMERICA Foreword This report describes the most used ice control practices applied to hydroelectric generation in North America, with a special emphasis on practical considerations. The subjects covered include the control of ice cover formation and decay, ice jamming, frazil ice at the water intakes, and their impact on the optimization of power generation and on the riparians. This report was prepared by Marcel Paul Raymond Energie for the benefit of HUVA - Energiforsk’s working group for hydrological development. HUVA incorporates R&D- projects, surveys, education, seminars and standardization. The following are delegates in the HUVA-group: Peter Calla, Vattenregleringsföretagen (ordf.) Björn Norell, Vattenregleringsföretagen Stefan Busse, E.ON Vattenkraft Johan E. Andersson, Fortum Emma Wikner, Statkraft Knut Sand, Statkraft Susanne Nyström, Vattenfall Mikael Sundby, Vattenfall Lars Pettersson, Skellefteälvens vattenregleringsföretag Cristian Andersson, Energiforsk E.ON Vattenkraft Sverige AB, Fortum Generation AB, Holmen Energi AB, Jämtkraft AB, Karlstads Energi AB, Skellefteå Kraft AB, Sollefteåforsens AB, Statkraft Sverige AB, Umeå Energi AB and Vattenfall Vattenkraft AB partivipates in HUVA. Stockholm, November 2015 Cristian -

Lacs Et Cours D'eau Du Québec Où La Présence Du Myriophylle À Épis (Myriophyllum Spicatum) a Été Rapportée – Juin 20

Lacs et cours d’eau du Québec où la présence du myriophylle à épis (Myriophyllum spicatum) a été rapportée – Juin 2021 Nom du plan d’eau Région(s) Municipalité(s) Lacs (171) Lac Dufault Abitibi-Témiscamingue Rouyn-Noranda Lac Noranda Abitibi-Témiscamingue Rouyn-Noranda Lac Opasatica Abitibi-Témiscamingue Rouyn-Noranda Lac Osisko Abitibi-Témiscamingue Rouyn-Noranda Lac Pelletier Abitibi-Témiscamingue Rouyn-Noranda Lac Renault Abitibi-Témiscamingue Rouyn-Noranda Lac Rouyn Abitibi-Témiscamingue Rouyn-Noranda Lac du Gros Ruisseau Bas-Saint-Laurent Mont-Joli, Saint-Joseph-de-Lepage Lac Témiscouata Bas-Saint-Laurent Témiscouata-sur-le-Lac Lac Delage Capitale-Nationale Lac-Delage Lac McKenzie Capitale-Nationale Lac-Beauport Lac Saint-Augustin Capitale-Nationale Saint-Augustin-de-Desmaures Lac Saint-Charles Capitale-Nationale Québec, Stoneham-Tewkesbury Lac Sergent Capitale-Nationale Lac-Sergent Lacs Laberge Capitale-Nationale Québec Lac Joseph Centre-du-Québec Inverness, Saint-Ferdinand, Saint-Pierre-Baptiste Lac Rose Centre-du-Québec Sainte-Marie-de-Blandford Lac Saint-Paul Centre-du-Québec Bécancour Lac William Centre-du-Québec Saint-Ferdinand Réservoir Beaudet Centre-du-Québec Victoriaville Lac de l’Est Chaudière-Appalaches Disraeli Lac des Abénaquis Chaudière-Appalaches Sainte-Aurélie Lac du Huit Chaudière-Appalaches Adstock Lac Gobeil Côte-Nord Les Bergeronnes, Sacré-Coeur Lac Jérôme Côte-Nord Les Bergeronnes Étang O’Malley Estrie Austin Estrie, Chaudière- Lac Aylmer Stratford, Disraeli, Weedon, Beaulac-Garthby Appalaches Lac Bran de Scie -

2.6 Settlement Along the Ottawa River

INTRODUCTION 76 2.6 Settlement Along the Ottawa River In spite of the 360‐metre drop of the Ottawa Figure 2.27 “The Great Kettle”, between its headwaters and its mouth, the river has Chaudiere Falls been a highway for human habitation for thousands of years. First Nations Peoples have lived and traded along the Ottawa for over 8000 years. In the 1600s, the fur trade sowed the seeds for European settlement along the river with its trading posts stationed between Montreal and Lake Temiskaming. Initially, French and British government policies discouraged settlement in the river valley and focused instead on the lucrative fur trade. As a result, settlement did not occur in earnest until the th th late 18 and 19 centuries. The arrival of Philemon Source: Archives Ontario of Wright to the Chaudiere Falls and the new British trend of importing settlers from the British Isles marked the beginning of the settlement era. Farming, forestry and canal building complemented each other and drew thousands of immigrants with the promise of a living wage. During this period, Irish, French Canadians and Scots arrived in the greatest numbers and had the most significant impact on the identity of the Ottawa Valley, reflected in local dialects and folk music and dancing. Settlement of the river valley has always been more intensive in its lower stretches, with little or no settlement upstream of Lake Temiskaming. As the fur trade gave way to farming, settlers cleared land and encroached on First Nations territory. To supplement meagre agricultural earnings, farmers turned to the lumber industry that fuelled the regional economy and attracted new waves of settlers. -

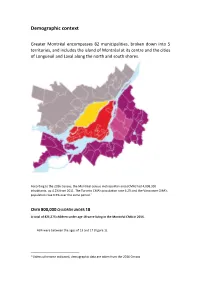

Demographic Context

Demographic context Greater Montréal encompasses 82 municipalities, broken down into 5 territories, and includes the island of Montréal at its centre and the cities of Longueuil and Laval along the north and south shores. According to the 2016 Census, the Montréal census metropolitan area (CMA) had 4,098,930 inhabitants, up 4.2% from 2011. The Toronto CMA’s population rose 6.2% and the Vancouver CMA’s population rose 6.5% over the same period.1 OVER 800,000 CHILDREN UNDER 18 A total of 821,275 children under age 18 were living in the Montréal CMA in 2016. — 46% were between the ages of 13 and 17 (Figure 1). 1 Unless otherwise indicated, demographic data are taken from the 2016 Census. Figure 1.8 Breakdown of the population under the age of 18 (by age) and in three age categories (%), Montréal census metropolitan area, 2016 Source: Statistics Canada (2017). 2016 Census, product no. 98-400-X2016001 in the Statistics Canada catalogue. The demographic weight of children under age 18 in Montréal is higher than in the rest of Quebec, in Vancouver and in Halifax, but is lower than in Calgary and Edmonton. While the number of children under 18 increased from 2001 to 2016, this group’s demographic weight relative to the overall population gradually decreased: from 21.6% in 2001, to 20.9% in 2006, to 20.3% in 2011, and then to 20% in 2016 (Figures 2 and 3). Figure 2 Demographic weight (%) of children under 18 within the overall population, by census metropolitan area, Canada, 2011 and 2016 22,2 22,0 21,8 21,4 21,1 20,8 20,7 20,4 20,3 20,2 20,2 25,0 20,0 19,0 18,7 18,1 18,0 20,0 15,0 10,0 5,0 0,0 2011 2016 Source: Statistics Canada (2017). -

Appendix a IAMGOLD Côté Gold Project Aboriginal Consultation Plan (Previously Submitted to the Ministry of Northern Development and Mines in 2013

Summary of Consultation to Support the Côté Gold Project Closure Plan Côté Gold Project Appendix A IAMGOLD Côté Gold Project Aboriginal Consultation Plan (previously submitted to the Ministry of Northern Development and Mines in 2013 Stakeholder Consultation Plan (2013) TC180501 | October 2018 CÔTÉ GOLD PROJECT PROVINCIAL INDIVIDUAL ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT PROPOSED TERMS OF REFERENCE APPENDIX D PROPOSED STAKEHOLDER CONSULTATION PLAN Submitted to: IAMGOLD Corporation 401 Bay Street, Suite 3200 Toronto, Ontario M5H 2Y4 Submitted by: AMEC Environment & Infrastructure, a Division of AMEC Americas Limited 160 Traders Blvd. East, Suite 110 Mississauga, Ontario L4Z 3K7 July 2013 TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE 1.0 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................ 1-1 1.1 Introduction ......................................................................................................... 1-1 1.2 Provincial EA and Consultation Plan Requirements ........................................... 1-1 1.3 Federal EA and Consultation Plan Requirements .............................................. 1-2 1.4 Responsibility for Plan Implementation .............................................................. 1-3 2.0 CONSULTATION APPROACH ..................................................................................... 2-1 2.1 Goals and Objectives ......................................................................................... 2-1 2.2 Stakeholder Identification .................................................................................. -

Basque Presence in the St. Lawrence Estuary Dominique Lalande

Northeast Historical Archaeology Volume 18 Article 3 1989 Archaeological Excavations at Bon-Désir: Basque Presence in the St. Lawrence Estuary Dominique Lalande Follow this and additional works at: http://orb.binghamton.edu/neha Part of the Archaeological Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Lalande, Dominique (1989) "Archaeological Excavations at Bon-Désir: Basque Presence in the St. Lawrence Estuary," Northeast Historical Archaeology: Vol. 18 18, Article 3. https://doi.org/10.22191/neha/vol18/iss1/3 Available at: http://orb.binghamton.edu/neha/vol18/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by The Open Repository @ Binghamton (The ORB). It has been accepted for inclusion in Northeast Historical Archaeology by an authorized editor of The Open Repository @ Binghamton (The ORB). For more information, please contact [email protected]. Archaeological Excavations at Bon-Désir: Basque Presence in the St. Lawrence Estuary Cover Page Footnote The er search work presented in this article is part of a project undertaken by the research group on native peroples and fishermen in eastern North America in the 16th and 17th centuries. This multidisciplinary project, directed by Laurier Turgeon of the Célat at Laval University, consists of historical, archaeological, literary, and ethnological studies. Under the supervision of Marcel Moussette, I had the opportunity to supervise the archaeological work, which was focused on finding traces of previous European occupations in the St. Lawrence estuary. I would like to express my gratitude to Laurier Turgeon, Marcel Moussette, Pierre Drouin, and Pierre Beaduet for their comments. The final drawings were prepared by Danielle Filion, the maps by Jean-Yves Pintal, and the artifact photographs by Paul Laliberté. -

Autres Que Du Salaire) Ville / Municipalité De Kazabazua 2 Arrondissement

ABCDEFG HIJKLM LISTE DES PARTICULIERS ET/OU SOCIÉTÉS AINSI QUE DES MONTANTS VERSÉS 1 (Autres que du salaire) Ville / Municipalité de Kazabazua 2 Arrondissement : Personne ressource : Pierre Vaillancourt Numéro de téléphone : (819) 467-2852 3 4 Numéro Montant total versé par année $ d'assurance Numéro Numéro social d'entreprise et/ de TPS Adresse complète Renseignements complémentaires 5 (NAS() ou (RC) ou (RT) Nom (no, rue, ville, province, code postal) 2013 2014 2015 2016 (personne contact et no de téléphone) 6 1 BOUTHILIER THERESE SALOMON 1101-150, RUE MACLAREN, OTTAWA ONTARIO, K2P 0L2 1 680.60 7 2 CARON JEAN-PIERRE, CHARRON MARTHE 1463 MONTEE DE LA SOURCE, CANTLEY QUEBEC, J8V 3K2 139.68 (819) 457-1957 8 3 FISHER SUSAN ELIZABETH 512, BRIERWOOD AVE, OTTAWA, K2A 2H5 466.37 (613) 728-3360 9 4 GAGNON LYNNE 573, ROUTE 105, KAZABAZUA QUEBEC, J0X 1X0 144.62 (819) 467-5185 VALERIE, 117, CHEMIN DE MULLIGAN FERRY, 10 5 LACHAPELLE-PETRIN KATHLEEN, PETRIN KAZABAZUA, J0X 1X0 160.87 (613) 866-6494 11 6 LAFRENIERE MAURICE 15, CHEMIN MARKS, GRACEFIELD, QUEBEC, J0X 1W0 414.70 (819) 463-2152 12 7 LARENTE JEAN-CLAUDE 2944 SAINT-LOUIS APP 4, GATINEAU QUEBEC, J8V 3X6 196.43 (819) 827-7662 A-S GUY GREGOIRE, 30, RUE DE VENDOME, GATINEAU, 13 8 LUMINAIRES G. GREGOIRE INC QUEBEC, J8T 1V3 240.91 (450) 454-2085 A-S GUY GREGOIRE, 30, RUE DE VENDOME, GATINEAU, 14 9 LUMINAIRES G. GREGOIRE INC QUEBEC, J8T 1V3 667.44 (514) 884-0990 15 10 MANTHA CLAUDE, ST-LOUIS ANNE 503, RUE GRAVELINE, GATINEAU, J8P 3G9 859.31 16 11 PECK RANDY R R 3 135 HIGHWAY 105, WAKEFIELD QUEBEC, J0X 3G0 262.66 (819) 459-2424 17 12 PETRIN LYNE 467 RUE GRAVELINE, GATINEAU QUEBEC, J8P 3J9 32.28 (819) 669-1215 C/S LAWRENCE MARKS, 25 NANOOK, OTTAWA ONTARIO, 18 13 RAMSAY HILDA ELIZABETH K2L 2A6 663.12 (613) 828-9024 19 14 ROSS TIFFANY 53 ELMDALE DR, WELLINGTON ONTARIO, K0K 3L0 175.51 (613) 399-2432 LESLIE, 10, JINGLETOWN RD, KAZABAZUA, QUEBEC, J0X 20 15 TANNER DAVID GEORGE, QUINN CYNTHIA 1X0 740.31 (819) 467-3749 11 CHEMIN DUPONT C.P. -

Lalaurentie05.Pdf

Bulletin de La Société d’histoire et de généalogie Bulletin de La Société d’histoire et de généalogie des Hautes-Laurentides des Hautes-Laurentides Volume 1, numéro 4 Mars 2009 5 $ Numéro 5 Automne 2009 5 $ Dossier Les Algonquins (Anishinàbeg) 6000 ans sur la Lièvre Aperçu du monde de vie Spiritualité Rites et cérémonies Kitigan Zibi (Maniwaki) La famille Mackanabé La gare de Mont-Laurier a 100 ans! 1 La Laurentie est publiée 4 fois par année par Sommaire La Société d’histoire et de généalogie des Hautes- Laurentides 385, rue du Pont, C.P. 153, Mont-Laurier (Québec) J9L 3G9 Propos à l’air libre 3 Téléphone : 819-623-1900 Télécopieur : 819-623-7079 Courriel : [email protected] Des nouvelles de votre Société 4 Site internet : www.genealogie.org/club/shrml/ Dossier : Les Anishinàbeg Heures d’ouverture : Du lundi au vendredi, de 9 h à 12 h et de 13 h à 17 h. Origine du mot Anishinàbe 7 Quelques mots Anishinàbeg 7 Rédacteur en chef : Gilles Deschatelets Répartition géographique 7 Équipe de rédaction : Aperçu du monde de vie 8 Suzanne Guénette, Louis-Michel Noël, Luc Coursol, Geneviève Piché, Heidi Weber. Le canot d’écorce 14 Spiritualité 16 Impression : Imprimerie L’Artographe Croyances 17 Conseil d’administration 2008-2009 : Quelques rites et cérémonies 18 Gilles Deschatelets (président), Shirley Duffy (vice-prési- Le collège Manitou 19 dente), Daniel Martin (trésorier), Gisèle L. Lapointe (secrétaire), Marguerite L. Lauzon (administratrice), La réserve de rivière Désert 20 Danielle Ouimet (administratrice). Des revendications 21 Nos responsables : Généalogie : Daniel Martin, Louis-Michel Noël Responsable administrative et webmestre : Suzanne Guénette Personne ressource : Denise Florant Dufresne.