View Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

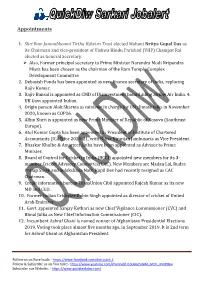

Appointments 1. Shri Ram Janmabhoomi Tirtha Kshetra Trust

Appointments 1. Shri Ram Janmabhoomi Tirtha Kshetra Trust elected Mahant Nritya Gopal Das as its Chairman and vice-president of Vishwa Hindu Parishad (VHP) Champat Rai elected as General Secretary. Also, Former principal secretary to Prime Minister Narendra Modi Nripendra Misra has been chosen as the chairman of the Ram Temple Complex Development Committee 2. Debasish Panda has been appointed as new finance secretary of India, replacing Rajiv Kumar. 3. Rajiv Bansal is appointed as CMD of Disinvestment bound ailing airline Air India. 4. UK Govt appointed Indian. 4. Origin person Alok Sharma as minister in charge for UN climate talks in November 2020, known as COP26. 5. Albin Kurti is appointed as new Prime Minister of Republic of Kosovo (Southeast Europe). 6. Atul Kumar Gupta has been appointed as President of Institute of Chartered Accountants (ICAI) for 2020-21, with Nihar Niranjan Jambusaria as Vice President. 7. Bhaskar Khulbe & Amarjeet Sinha have been appointed as Advisor to Prime Minister. 8. Board of Control for Cricket in India (BCCI) appointed new members for its 3- member Cricket Advisory Committee(CAC). New Members are Madan Lal, Rudra Pratap Singh and Sulakshana Naik. Kapil Dev had recently resigned as CAC Chairman. 9. Credit information bureau TransUnion Cibil appointed Rajesh Kumar as its new MD and CEO. 10. Former Indian Cricketer Robin Singh appointed as director of cricket of United Arab Emirates. 11. Govt. appointed Sanjay Kothari as new Chief Vigilance Commissioner (CVC) and Bimal Julka as New Chief Information Commissioner (CIC). 12. Incumbent Ashraf Ghani is named winner of Afghanistan Presidential Elections 2019. -

Admiral Sunil Lanba, Pvsm Avsm (Retd)

ADMIRAL SUNIL LANBA, PVSM AVSM (RETD) Admiral Sunil Lanba PVSM, AVSM (Retd) Former Chief of the Naval Staff, Indian Navy Chairman, NMF An alumnus of the National Defence Academy, Khadakwasla, the Defence Services Staff College, Wellington, the College of Defence Management, Secunderabad, and, the Royal College of Defence Studies, London, Admiral Sunil Lanba assumed command of the Indian Navy, as the 23rd Chief of the Naval Staff, on 31 May 16. He was appointed Chairman, Chiefs of Staff Committee on 31 December 2016. Admiral Lanba is a specialist in Navigation and Aircraft Direction and has served as the navigation and operations officer aboard several ships in both the Eastern and Western Fleets of the Indian Navy. He has nearly four decades of naval experience, which includes tenures at sea and ashore, the latter in various headquarters, operational and training establishments, as also tri-Service institutions. His sea tenures include the command of INS Kakinada, a specialised Mine Countermeasures Vessel, INS Himgiri, an indigenous Leander Class Frigate, INS Ranvijay, a Kashin Class Destroyer, and, INS Mumbai, an indigenous Delhi Class Destroyer. He has also been the Executive Officer of the aircraft carrier, INS Viraat and the Fleet Operations Officer of the Western Fleet. With multiple tenures on the training staff of India’s premier training establishments, Admiral Lanba has been deeply engaged with professional training, the shaping of India’s future leadership, and, the skilling of the officers of the Indian Armed Forces. On elevation to Flag rank, Admiral Lanba tenanted several significant assignments in the Navy. As the Chief of Staff of the Southern Naval Command, he was responsible for the transformation of the training methodology for the future Indian Navy. -

Vividh Bharati Was Started on October 3, 1957 and Since November 1, 1967, Commercials Were Aired on This Channel

22 Mass Communication THE Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, through the mass communication media consisting of radio, television, films, press and print publications, advertising and traditional modes of communication such as dance and drama, plays an effective role in helping people to have access to free flow of information. The Ministry is involved in catering to the entertainment needs of various age groups and focusing attention of the people on issues of national integrity, environmental protection, health care and family welfare, eradication of illiteracy and issues relating to women, children, minority and other disadvantaged sections of the society. The Ministry is divided into four wings i.e., the Information Wing, the Broadcasting Wing, the Films Wing and the Integrated Finance Wing. The Ministry functions through its 21 media units/ attached and subordinate offices, autonomous bodies and PSUs. The Information Wing handles policy matters of the print and press media and publicity requirements of the Government. This Wing also looks after the general administration of the Ministry. The Broadcasting Wing handles matters relating to the electronic media and the regulation of the content of private TV channels as well as the programme matters of All India Radio and Doordarshan and operation of cable television and community radio, etc. Electronic Media Monitoring Centre (EMMC), which is a subordinate office, functions under the administrative control of this Division. The Film Wing handles matters relating to the film sector. It is involved in the production and distribution of documentary films, development and promotional activities relating to the film industry including training, organization of film festivals, import and export regulations, etc. -

India – Brunei Relations the Contacts Between India and Brunei Have

India – Brunei Relations The Contacts between India and Brunei have historical and cultural roots as extension of India’s relations with peninsular Malaysia and the Indonesian Island. The diplomatic relations between India and Brunei were established in May 1984. The interest in upgrading bilateral relations started in friendly meetings between late Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi and the Sultan of Brunei at CHOGM meetings, etc. In response to Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi’s invitation, the Sultan of Brunei paid a State visit to India in September 1992 and Indian resident diplomatic mission was opened in Brunei on 18 May, 1993. Brunei set up its High Commission in India in 12 August, 1992. By virtue of their common membership of UN, NAM, Commonwealth and ARF etc and as developing countries with strong traditional and cultural ties, Brunei and India enjoy a fair degree of commonality in their perceptions on major international issues. Brunei is supportive of India’s ‘Look East Policy welcomes ‘Act East’ policy and expansion and deepening of cooperation with ASEAN. Brunei took over as India- ASEAN Coordinator from July 2012 for three years. The visit of the Sultan of Brunei to India in May 2008 was a landmark in India-Brunei relations. Five MoUs/Agreements were signed during the visit on BIPA, ICT, Culture, Trade and Space. India participated at the BRIDEX (The Brunei Darussalam International Defence Exhibition & Conference) in 2009 and 2011. Indian Navy Ships INS Ranvir and INS Jyoti visited Brunei in May 2011 on goodwill visits. Indian Coast Guard Ship, Sagar, the first by a coast guard vessel, visited Brunei on 27-30 June, 2011 while INS Airavat visited Brunei on 4-9 July, 2011 to participate in the first-ever Brunei International Fleet Review to mark the 50th anniversary of Royal Brunei Armed Forces. -

Singapore and India Step up Maritime Engagements and Renew Commitment to Defence Partnership at Second Defence Ministers’ Dialogue

Singapore and India Step Up Maritime Engagements and Renew Commitment to Defence Partnership at Second Defence Ministers’ Dialogue 29 Nov 2017 Minister for Defence Dr Ng Eng Hen (left) with Indian Minister for Defence Nirmala Sitharaman (right) at the second India-Singapore Defence Ministers' Dialogue in New Delhi, India. Minister for Defence Dr Ng Eng Hen met Indian Minister for Defence Nirmala Sitharaman for the second India-Singapore Defence Ministers' Dialogue (DMD) today. During the DMD, both Ministers reaffirmed the strong and long-standing defence relationship, and discussed ways to strengthen bilateral cooperation. Dr Ng and Ms 1 Sitharaman also exchanged views on strategic regional security and defence matters, and welcomed India's proposal of institutionalising engagements, including maritime exercises, with Southeast Asian countries. They acknowledged the good progress made following the signing of the Defence Cooperation Agreement (DCA) in November 2015, such as the convening of the first Defence Industry Working Group in May 2016, and the inaugural Singapore-India DMD in June 2016. Following the DMD, Dr Ng and Ms Sitharaman witnessed the exchange of the inaugural Navy Bilateral Agreement between both Chiefs of Navy, in which both sides agree to increase cooperation in maritime security, increase visits to each other's ports, and facilitate mutual logistics support. The Navy Bilateral Agreement was signed by Singapore's Permanent Secretary of Defence Mr Chan Yeng Kit and India's Defence Secretary Sanjay Mitra. The conclusion of the Navy Bilateral Agreement, together with the existing Army and Air Force Bilateral Agreements, is testament to the breadth and depth of military-to-military ties between the Singapore Armed Forces and the Indian Armed Forces. -

Sainik 1-15 August English.Pdf

2018 1-15 August Vol 65 No 15 ` 5 SAINIK Samachar Readers are requested for their valuable suggestions about Sainik Samachar Kargil Vijay Diwas Celebrations-2018 pic: DPR Photo Division The Chief of the Air Staff, Air Chief Marshal BS Dhanoa addressing the inaugural session of seminar on ‘Technology Infusion and Indigenisation of Indian Air Force’, in New Delhi on July 27, 2018. General Bipin Rawat COAS commended retiring officers for their service to the Nation and bid them adieu. These officers superannuated on July 31, 2018. In This Issue Since 1909 DefenceBIRTH MinisterANNIVERSARY hands CELEBRATIONS over High 4 Power Multi-Fuel Engines… (Initially published as FAUJI AKHBAR) Vol. 65 q No 15 10 - 24 Shravana, 1940 (Saka) 1-15 August 2018 The journal of India’s Armed Forces published every fortnight in thirteen languages including Hindi & English on behalf of Ministry of Defence. It is not necessarily an organ for the expression of the Government’s defence policy. The published items represent the views of respective writers and correspondents. Editor-in-Chief Hasibur Rahman Senior Editor Ms Ruby T Sharma Kargil Vijay Diwas 5 RRM inaugurates Air 6 Editor Ehsan Khusro Celebrations-2018 Defence India – 2018… Sub Editor Sub Maj KC Sahu Coordination Kunal Kumar Business Manager Rajpal Our Correspondents DELHI: Col Aman Anand; Capt DK Sharma VSM; Wg Cdr Anupam Banerjee; Manoj Tuli; Nampibou Marinmai; Divyanshu Kumar; Photo Editor: K Ramesh; ALLAHABAD: Wg Cdr Arvind Sinha; BENGALURU: Officiating M Ponnein Selvan;CHANDIGARH: Anil Gaur; CHENNAI: -

Moving Forward EU-India Relations. the Significance of the Security

Moving Forward EU-India Relations The Significance of the Security Dialogues edited by Nicola Casarini, Stefania Benaglia and Sameer Patil Edizioni Nuova Cultura Output of the project “Moving Forward the EU-India Security Dialogue: Traditional and Emerging Issues” led by the Istituto Affari Internazionali (IAI) in partnership with Gate- way House: Indian Council on Global Relations (GH). The project is part of the EU-India Think Tank Twinning Initiative funded by the European Union. First published 2017 by Edizioni Nuova Cultura for Istituto Affari Internazionali (IAI) Via Angelo Brunetti 9 – I-00186 Rome – Italy www.iai.it and Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations Colaba, Mumbai – 400 005 India Cecil Court, 3rd floor Copyright © 2017 Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations (ch. 2-3, 6-7) and Istituto Affari Internazionali (ch. 1, 4-5, 8-9) ISBN: 9788868128531 Cover: by Luca Mozzicarelli Graphic composition: by Luca Mozzicarelli The unauthorized reproduction of this book, even partial, carried out by any means, including photocopying, even for internal or didactic use, is prohibited by copyright. Table of Contents Abstracts .......................................................................................................................................... 9 Introduction ................................................................................................................................. 15 1. Maritime Security and Freedom of Navigation from the South China Sea and Indian Ocean to the Mediterranean: -

Indian Ministry of Defence Annual Report 2011-2012

ANNUAL REPORT 2011-2012 Ministry of Defence Government of India Joint Army-Air Force Exercise ‘Vijayee Bhava’ Army-Air Force Exercise ‘Vijayee Joint Front Cover :- Contingent of the Para-Regiment at the Republic Day Parade-2012 (Clockwise) AGNI-IV Test IAF’s Mi-17 V5 Helicopter Coast Guard Interceptor Boat ICGS C-153 Annual Report 2011-12 Ministry of Defence Government of India CONTENTS 1. Security Environment 1 2. Organisation and Functions of the Ministry of Defence 9 3. Indian Army 17 4. Indian Navy 33 5. Indian Air Force 43 6. Coast Guard 49 7. Defence Production 57 8. Defence Research and Development 93 9. Inter Service Organizations 113 10. Recruitment and Training 131 11. Resettlement and Welfare of Ex-Servicemen 153 12. Cooperation between the Armed Forces and Civil Authorities 167 13. National Cadet Corps 177 14. Defence Relations with Foreign Countries 189 15. Ceremonial, Academic and Adventure Activities 199 16. Activities of Vigilance Units 213 17. Empowerment and Welfare of Women 219 Appendices I Matters dealt with by the Departments of the Ministry of Defence 227 II Ministers, Chiefs of Staff and Secretaries who were in 231 position from January 1, 2011 onwards III Summary of latest Comptroller & Auditor General 232 (C&AG) Report on the working of Ministry of Defence IV Position of Action Taken Notes (ATNs) as on 31.12.2011 in respect 245 of observations made in the C&AG Reports/PAC Reports 3 4 1 SECURITY ENVIRONMENT IAF SU-30s dominating the air space 1 The emergence of ideology linked terrorism, the spread of small arms and light weapons(SALW), the proliferation of WMD (Weapons of Mass Destruction) and globalisation of its economy are some of the factors which link India’s security directly with the extended neighbourhood 1.1 India has land frontiers extending Ocean and the Bay of Bengal. -

The Alma Mater of the PROFESSIONAL JOURNAL of Marine Engineers MARINE ENGINEERING

RESTRICTED JME “The Prime Mover” The Alma Mater of THE PROFESSIONAL JOURNAL OF Marine Engineers MARINE ENGINEERING Volume 74 Jul 17 ‘ONBOARD ENERGY MANAGEMENT AND ENVIRONMENT PROTECTION’ Ser Contents Page 01. Trials with Bio-Diesel on a Marine Diesel Engine in 14 Indian Navy Capt Mohit Goel, NM 02. Energy Savings Through Optimizing Machinery 21 Load and Exploitation Cdr M Sujit 03. Oil Water Separation Using Magnetite Powder 31 Applications Cdr Ayyappa Ramesh, SLt Hitesh Rana, SLt Vinay B Sonna, SLt Sudeep Pilpia, SLt Aradhya Kumar 04. Waste Heat Recovery System (WHRS) 37 Lt Cdr NS Kaushik GENERAL MARINE ENGINEERING / NOTES FROM SEA 05. Innovative Repair of SME CAC at Sea – INS Tir 45 Cdr Samir Bera, Lt Cdr BK Ganapathy 06. A Short Note on Understanding Diesel Transients 53 in the Framework of Indian Naval Requirements Cdr Girish Gokul JME Vol. 74 1 RESTRICTED RESTRICTED 07. Innovative Arrangement for Measurement of Suction 67 Rate of Submersible Pumps – INS Deepak Lt Cdr Nanda Kumar 08. CFD Analysis of Plane and Circular Couette Flow 71 Lt Cdr Pranit Himanshu Rana, Mid Shashi Kumar, Mid Ayush Kumar, Mid Amit Singh 09. Defect Rectification on Port Stabiliser - Teg Class 77 Lt Sunit Sharma 10. Knowledge Enabler Bay – GTTT (Mbi) 88 Cdr AP Singh 11. Experimental Investigation and Analysis of Friction 95 Stir Welding Lt Cdr Vivek Anand, Cdt KP Vignesh Rao, Cdt Shakti Kumar, Cdt Piyush Bhatt, Cdt Akash Sharma 12. Sea State 6 – Poem 106 Lt Vipul Ruperee Staff Student Projects 107 Kaleidoscope of Development & Training Activities 115 Undertaken at Shivaji On the Horizon 126 Awards 137 JME Vol. -

Erospace & Defence Eview

VI/2013 ARerospace &Defence eview INS Vikramaditya (R33) commissioned Russian aircraft with IN India’s Maritime Options Dubai Air Show 2013 MBDA Missiles The Sea Gripen CFM VI/2013 VI/2013 Aerospace &Defence Review 42 ‘The Carrier that endorses the view that “a well- 102 An Enduring Story came in from the funded navy can become both As Part II of the article on Indo- a provider of security and an Russian co-operation in military Cold’ expression of India’s willingness aviation, the ongoing extent of Vayu was the only trade journal to shoulder great-power Russian aircraft in service with represented at Severodvinsk responsibilities.” India’s Naval Air Arm is reviewed INS Vikramaditya (R33) commissioned Russian aircraft with IN when the Indian Naval Ensign by Pushpindar Singh. The Indian India’s Maritime Options Dubai Air Show 2013 was hoisted on stern of INS Navy’s inventory today includes The Sea Gripen MBDA Missiles Vikramaditya, and is therefore NAMEXPO 2013 Russian-origin long range able to bring this exclusive, 68 India’s first Naval and Maritime maritime patrol aircraft, AEW INS Vikramaditya during sea trials in Russian comprehensive report Expo was held at Cochin, which and ASW helicopters, supersonic waters (photo : Sevmash) on commissioning of Indian included conferences involving multi-role fighters - an enduring Navy’s new aircraft carrier. the Indian Navy, Coast Guard, story in its sixth decade. This account is supported with Ministry of MSME and NSIC. other ‘exclusives’ including There was both international EDITORIAL PANEL an informal interaction with and domestic participation, MANAGING EDITOR Defence Minister AK Antony and with timely papers presented by Vikramjit Singh Chopra a tour of vital sections of the ship. -

Indian Ministry of Defence Annual Report 2003

AnnualAnnual ReportReport 2003-2004 Ministry of Defence Government of India ANNUAL REPORT 2003-04 Ministry of Defence Government of India Front Cover: ‘Tejas’ the world’s smallest light weight multi-role aircraft designed by DRDO to meet the demands of Indian Air Force, has sucessfully completed 200 flight tests. Back Cover: ‘INS Talwar’, the Stealth Frigate, inducted in the Indian Navy in July 2003 adds to Navy’s punch. CONTENTS 1. Security Environment 5 2. Organisation and Functions of the Ministry of Defence 15 3. Indian Army 25 4. Indian Navy 39 5. Indian Air Force 49 6. Coast Guard 59 7. Defence Production 71 8. Defence Research and Development 97 9. Inter-Service Organisations 115 10. Recruitment and Training 127 11. Resettlement and Welfare of Ex-Servicemen 147 12. Cooperation Between the Armed Forces & Civil Authorities 165 13. National Cadet Corps 173 14. Defence Relations With Foreign Countries 183 15. Ceremonial, Academic and Adventure Activities 201 16. Activities of Vigilance Units 211 17. Empowerment and Welfare of Women 213 Appendices I. Matters dealt with by the Departments of the Minstry of Defence 219 II. Ministers, Chiefs of Staff & Secretaries who were in position from April 1, 2003 onwards 223 III. Summary of latest C&AG Report on the working of Ministry of Defence 224 11 SECURITY ENVIRONMENT Security environment around India underlines the need for a high level of vigilance and defence preparedness Few countries face the range of security challenges, concerns and threats that India faces, from terrorism and low- intensity conflict to nuclear weapons and missiles, in its neighbourhood. -

Planning and Management of Refits of Indian Naval Ships

Planning and Management of Refits of Indian Naval Ships Report of the Comptroller and Auditor General of India for the year ended March 2013 Union Government Defence Services (Navy) Report No. 31 of 2013 (Performance Audit) PerformanceAuditofPlanningandManagementofRefitsofIndianNavalShips CONTENTS Sl. No./ Subject Page Para No. 1. Preface i 2. Executive Summary ii 3. Chapter 1 : Introduction 1 1.1 Background 1 1.2 Refit and its types 1 1.3 Organisational Structure 3 1.4 Repair Yards 4 1.5 Financial Aspects 5 1.6 Reasons for selecting the topic 5 1.7 Audit Objectives 6 1.8 Scope of Audit 6 1.9 Sources of Audit Criteria 7 1.10 Acknowledgement 7 1.11 Audit Methodology 8 4. Chapter 2 : Planning and Execution 9 of Refits 2.1 How are the refits planned? 9 2.2 Execution of Refits 11 2.3 Excess utilisation of dry docking days 18 2.4 Off-loading of refits 18 5. Chapter 3 : Mid Life Update of Ships 23 3.1 Mid Life Updates: The Rationale, Need and the 23 Candidate Ships 3.2 Planning and Implementation of MLUs 24 3.3 Financial Management 29 3.4 Efficacy of MLU 31 3.5 Procurement of MLU equipment 34 PerformanceAuditofPlanningandManagementofRefitsofIndianNavalShips 6. Chapter 4: Infrastructure, Human 41 Resources and Supply of Spares 4.1 Background 41 4.2 Infrastructure Facilities 41 4.3 Earlier Audit Findings 43 4.4 Creation of Additional infrastructure 43 4.5 Human Resources 48 4.6 Supply of Spares 54 4.7 Local purchase of Stores 59 7. Chapter 5 : Cost Accounting of Refits and 62 MLUs 5.1 Introduction 62 5.2 Cost Accounting System in Dockyard 63 5.3 Delay in preparation of AWPA 64 5.4 Difficulties in ascertaining cost of a refit 65 5.5 Delay in closing of work orders 65 5.6 Non-preparation of cost accounts 66 8.