Social Protection and Rights

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Multi-Scale Assessment of Risks to Environmental Hazards in Coastal Area of Bangladesh

Multi-Scale Assessment of Risks to Environmental Hazards in Coastal Area of Bangladesh by Momtaz Jahan MASTER OF SCIENCE IN WATER RESOURCES DEVELOPMENT INSTITUTE OF WATER AND FLOOD MANAGEMENT BANGLADESH UNIVERSITY OF ENGINEERING AND TECHNOLOGY December, 2018 Multi-Scale Assessment of Risks to Environmental Hazards in Coastal Area of Bangladesh A thesis submitted by Momtaz Jahan Student ID: 1014282024 Session: October 2014 In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE IN WATER RESOURCES DEVELOPMENT INSTITUTE OF WATER AND FLOOD MANAGEMENT BANGLADESH UNIVERSITY OF ENGINEERING AND TECHNOLOGY December, 2018 ii BANGLADESH UNIVERSITY OF ENGINEERING AND TECHNOLOGY INSTITUTE OF WATER AND FLOOD MANAGEMENT The thesis titled “Multi-Scale Assessment of Risks to Environmental Hazards in Coastal Area of Bangladesh” submitted by Momtaz Jahan, Student ID: 1014282024 F, Session: October, 2014 has been accepted as satisfactory in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Master of Science in Water Resources Development on 17 December, 2018. BOARD OF EXAMINERS .................................................. Dr. Mashfiqus Salehin Chairman Professor (Supervisor) Institute of Water and Flood Management Bangladesh University of Engineering and Technology, Dhaka ................................................. Dr. Sujit Kumar Bala Member Professor and Director (Ex-officio) Institute of Water and Flood Management Bangladesh University of Engineering and Technology, Dhaka ............................................... -

Utilization and Prospectus of Non-Timber Forest Products As Livelihood Materials Atanu Kumar Dasa*, Md

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.10.19.345223; this version posted October 19, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY 4.0 International license. Utilization and prospectus of non-timber forest products as livelihood materials Atanu Kumar Dasa*, Md. Asaduzzamanb, Md Nazrul Islamb a Department of Forest Biomaterials and Technology, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, SE- 90183 Umeå, Sweden. bForestry and Wood Technology Discipline, Khulna University, Khulna-9208, Bangladesh. Abstract A study was conducted to find out the present utilization of non-timber forest products of the Sundarbans and tries to find out the alternative uses of these resources. The Sundarbans is the largest mangrove forest in the world and proper utilization of all resources can get a chance to manage this forest in sustainable way. A questionnaire survey was conducted to get information about the utilization of non-timber forest products. It has been found that about 87% of the people are fully dependent and 13% of the people are partially dependent on the Sundarbans. Among minor forest products, golpata, honey and fish were used by 92%, 93% and 82% of people, respectively. Most of the people are unknown about the alternative use of minor forest products but there is a great chance to use them for better purposes. Alternative uses of these products will help to improve the forest conditions as well as the socio- economic conditions of the people adjacent to the Sundarbans. -

Learning from the Recent Past Extreme Climatic Events for Future Planning

Addressing Non-economic Losses and Damages Associated with Climate Change: Learning from the Recent Past Extreme Climatic Events for Future Planning Yohei Chiba and S.V.R.K. Prabhakar Addressing Non-economic Losses and Damages Associated with Climate Change: Learning from the Recent Past Extreme Climatic Events for Future Planning Edited by: Yohei Chiba and S.V.R.K. Prabhakar Contact [email protected] Institute for Global Environmental Strategies (IGES), Hayama, Japan APN website: http://www.apn-gcr.org/resources/items/show/1943 IGES website: https://www.iges.or.jp/en/natural-resource/ad/landd.html Suggested Citation Chiba, Y. and S.V.R.K. Prabhakar (Eds.). 2017. Addressing Non-economic Losses and Damages Associated with Climate Change: Learning from the Recent Past Extreme Climatic Events for Future Planning. Kobe, Japan: Asia-Pacific Network for Global Change Research (APN) and Institute for Global Environmental Strategies (IGES). Copyright © 2017 Asia-Pacific Network for Global Change Research APN seeks to maximise discoverability and use of its knowledge and information. All publications are made available through its online repository “APN E-Lib” (www.apn-gcr.org/resources/). Unless otherwise indicated, APN publications may be copied, downloaded and printed for private study, research and teaching purposes, or for use in non-commercial products or services. Appropriate acknowledgement of APN as the source and copyright holder must be given, while APN’s endorsement of users’ views, products or services must not be implied in any way. For reuse requests: http://www.apn-gcr.org/?p=10807 Table of Content List of Contributors ........................................................................................................ iii Acknowledgments ........................................................................................................ -

Khulna District College Eiin

Query1 KHULNA DISTRICT COLLEGE EIIN www.eduresultbd.com DISTRICT_NAME THANA_NAME INSTITUTE_NAME_NEW EIIN KHULNA BATIAGHATA ALAIPUR RAJBANDH HIGH SCHOOL 116847 KHULNA BATIAGHATA B L J HIGH SCHOOL 116839 KHULNA BATIAGHATA B.H.M.H. GIRLS HIGH SCHOOL 116855 KHULNA BATIAGHATA BAROARIA SECONDARY SCHOOL 116854 KHULNA BATIAGHATA BATIAGHATA SECONDARY SCHOOL 116837 KHULNA BATIAGHATA BATIAGHATA THANA H. Q. GIRLD HIGH SCHOOL 116834 KHULNA BATIAGHATA BATIAGHATA THANA H. Q. PILOT HIGH SCHOOL 116833 KHULNA BATIAGHATA BAYARBHANGA BISWANBHARA HIGH SCHOOL 116836 KHULNA BATIAGHATA BIRAT HIGH SCHOOL 116857 KHULNA BATIAGHATA DEUATALA HIGH SCHOOL 116841 KHULNA BATIAGHATA FULBARI HIGH SCHOOL 116846 KHULNA BATIAGHATA GAOGHARA ML. HIGH SCHOOL 116844 KHULNA BATIAGHATA HALIA BENODE BEHARI HIGH SCHOOL 116852 KHULNA BATIAGHATA HOGOL BUNIA HATBATI HIGH SCHOOL 116835 KHULNA BATIAGHATA J. K. A. G. SECONDRY SCHOOL 116848 KHULNA BATIAGHATA JALMA CHAKRAKHAKI SECONDARU SCHOOL 116838 KHULNA BATIAGHATA KHALSHI BUNIA G.P.B HIGH SCHOOL 116845 KHULNA BATIAGHATA PARBATIAGHATA GIRLS HIGH SCHOOL 116850 KHULNA BATIAGHATA PROGATI HIGH SCHOOL 116849 KHULNA BATIAGHATA PROGATIMADHYAMICK BIDYAPITH RAJBANDH 116851 KHULNA BATIAGHATA RASHOHAN GIRL'S HIGH SCHOOL 116840 KHULNA BATIAGHATA SARAWATI SECONDARY SCHOOL 116853 KHULNA BATIAGHATA SHIALI DANGA MULTI SECONDARY SCHOOL 116842 KHULNA BATIAGHATA SUKDARA HIGH SCHOOL 116856 KHULNA BATIAGHATA SURKHALI HIGH SCHOOL 116843 KHULNA BATIAGHATA BUNRABUD B.S.S DAKHIL MADRASAH 116864 KHULNA BATIAGHATA CHANDANMARIA ISLAMIA DAKHIL MADRASAH 127007 KHULNA -

Distribution of Ethnic Households, Population by Sex, Residence and Community

Table C-12 : Distribution of Ethnic Households, Population by Sex, Residence and Community Ethnic Ethnic Population in Main Groups Administrative Unit UN / MZ / ZL UZ Vill RMO Residence Population WA MH Community Households Monda Chakma Barmon Others Both Male Female 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 47 Khulna Zila Total 483 2054 1022 1032 1003 51 38 962 47 1 Khulna Zila 424 1808 892 916 1003 5 31 769 47 2 Khulna Zila 55 231 121 110 0 42 7 182 47 3 Khulna Zila 4 15 9 6 0 4 0 11 47 12 Batiaghata Upazila Total 2 22 21 1 0 0 0 22 47 12 1 Batiaghata Upazila 2 22 21 1 0 0 0 22 47 12 3 Batiaghata Upazila 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 47 12 11 Amirpur Union Total 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 47 12 23 Baliadanga Union Total 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 47 12 35 Batiaghata Union Total 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 47 12 35 1 Batiaghata Union 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 47 12 35 3 Batiaghata Union 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 47 12 47 Bhanderkote Union Total 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 47 12 59 Gangarampur Union Total 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 47 12 71 Jalma Union Total 2 22 21 1 0 0 0 22 47 12 83 Surkhali Union Total 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 47 17 Dacope Upazila Total 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 47 17 1 Dacope Upazila 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 47 17 2 Dacope Upazila 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 47 17 Chalna Paurashava 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 47 17 01 Ward No-01 Total 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 47 17 02 Ward No-02 Total 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 47 17 03 Ward No-03 Total 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 47 17 04 Ward No-04 Total 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 47 17 05 Ward No-05 Total 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 47 17 06 Ward No-06 Total 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 47 17 07 Ward No-07 Total 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 47 17 08 Ward No-08 Total 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 47 17 09 Ward No-09 Total 0 0 0 0 0 -

Living with the Risks of Cyclone Disasters in the South-Western Coastal Region of Bangladesh

environments Article Living with the Risks of Cyclone Disasters in the South-Western Coastal Region of Bangladesh Bishawjit Mallick 1,2,3, Bayes Ahmed 4,5,* and Joachim Vogt 3 1 International Migration Institute, University of Oxford, Oxford OX1 3TB, UK; [email protected] or [email protected] 2 Department of Political Science, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN 372 03, USA 3 Institute of Regional Science (IfR), Karlsruhe Institute of Technology (KIT), Karlsruhe 76131, Germany; [email protected] 4 Institute for Risk and Disaster Reduction, Department of Earth Sciences, University College London (UCL), Gower Street, London WC1E 6BT, UK 5 Department of Disaster Science and Management, Faculty of Earth and Environmental Sciences, University of Dhaka, Dhaka 1000, Bangladesh * Correspondence: [email protected] Academic Editors: Jason K. Levy and Peiyong Yu Received: 9 December 2016; Accepted: 4 February 2017; Published: 9 February 2017 Abstract: Bangladesh is one of the most disaster prone countries in the world. Cyclone disasters that affect millions of people, destroy homesteads and livelihoods, and trigger migration are common in the coastal region of Bangladesh. The aim of this article is to understand how the coastal communities in Bangladesh deal with the continuous threats of cyclones. As a case study, this study investigates communities that were affected by the Cyclone Sidr in 2007 and Cyclone Aila in 2009, covering 1555 households from 45 coastal villages in the southwestern region of Bangladesh. The survey method incorporated household based questionnaire techniques and community based focus group discussions. The pre-event situation highlights that the affected communities were physically vulnerable due to the strategic locations of the cyclone shelters nearer to those with social supreme status and the location of their houses in relatively low-lying lands. -

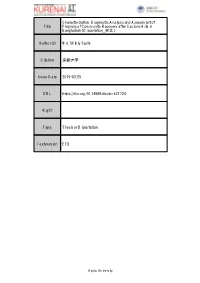

Characterization, Diagnostic Analysis and Assessment of Title Progress of Community Recovery After Cyclone Aila in Bangladesh( Dissertation 全文 )

Characterization, Diagnostic Analysis and Assessment of Title Progress of Community Recovery after Cyclone Aila in Bangladesh( Dissertation_全文 ) Author(s) Md, Shibly Sadik Citation 京都大学 Issue Date 2019-03-25 URL https://doi.org/10.14989/doctor.k21724 Right Type Thesis or Dissertation Textversion ETD Kyoto University Characterization, Diagnostic Analysis and Assessment of Progress of Community Recovery after Cyclone Aila in Bangladesh Md Shibly Sadik 2019 Characterization, Diagnostic Analysis and Assessment of Progress of Community Recovery after Cyclone Aila in Bangladesh A dissertation submitted in partial fulfilment for the requirement of Doctoral Degree in Civil and Earth Resources Engineering by Md Shibly Sadik Supervised by Professor Hajime Nakagawa Laboratory of Hydroscience and Hydraulic Engineering Department of Civil and Earth Resources Engineering Graduate School of Engineering Kyoto University Japan 2019 Abstract International policies of disaster management is undergoing a change due to emergence of Sendai Framework, Sustainable Development Goal, and local ongoing development. In case of countries like Bangladesh that are undergoing a rapid change in economic development, and where international aids, humanitarian organizations and NGOs play a vital role in post-disaster recovery, such international changes impact widely and deeply. Accordingly, National disaster management policies and priorities in Bangladesh are also undergoing a paradigm shift from post-disaster relief to pre-disaster preparedness. Such changes became evidently visible in Bangladesh after two recent devastating cyclone- Cyclone Sidr (strike in 2007) and Cyclone Aila (strike in 2009). New approaches of disaster recovery- Government-NGO partnership approach, Build Back Better (BBB) were adopted for post disaster recovery of Cyclone Sidr and Cyclone Aila. -

Evsjv‡`K †M‡RU, Awzwi³, A‡±Vei 29, 2017 সড়কস�েহর অ�েমািদত ��ণীিব�াস অ�যায়ী �ানীয় সরকার �েকৗশল অিধদ�েরর (এলিজইিড) আওতাধীন ইউিনয়ন সড়েকর হালনাগাদ তািলকা

† iwR÷vW© bs wW G - 1 evsjv ‡` k † M ‡ RU AwZwi³ msL¨v KZ…©c¶ KZ…©K cÖKvwkZ iweevi , A ‡ ±vei 2 9 , 201 7 MYcÖRvZš¿x evsjv ‡` k miKvi cwiKíbv Kwgkb ‡ fŠZ AeKvVv ‡ gv wefvM moK cwienb DBs cÖÁvcb ZvwiLt 19 A ‡ ±vei 2017 moK cwienb I gnvmoK wefv ‡ Mi AvIZvaxb moK I Rbc_ (mIR ) Awa`ßi Ges ¯ ’vbxq miKvi wefv ‡ Mi AvIZvaxb ¯ ’vbxq miKvi cÖ‡ KŠkj Awa`ßi (GjwRBwW) - Gi Kv ‡ Ri g ‡ a¨ ˆØZZv cwinvic~e©K †`‡ k myôz moK † bUIqvK© M ‡ o † Zvjvi j ‡ ÿ¨ miKvi KZ©„K Aby‡ gvw`Z † kÖYxweb¨vm I bxwZgvjv Abyhvqx mIR Awa`ßi Ges GjwRBwWÕi moKmg~‡ ni mgwš^Z ZvwjKv 11 - 02 - 2004 Zvwi ‡ L evsjv ‡` k † M ‡ R ‡ U cÖKvwkZ nq| cieZ©x ‡ Z 12 Ryb 2006 Zvwi ‡ L GjwRBwWÕi AvIZvaxb Dc ‡ Rjv I BDwbqb moK Ges ¯ ’vbxq miKvi cÖwZôvb (GjwRAvB) Gi AvIZvaxb MÖvg moKmg~‡ ni Avjv`v ZvwjKv evsjv ‡` k † M ‡ R ‡ U cÖKvwkZ nq| GjwRBwW Ges mIR Awa`ß ‡ ii Aaxb moKmg~‡ ni g vwjKvbvi ˆØZZv cwinv ‡ ii j ‡ ÿ¨ MwVZ ÕmoKmg~‡ ni cybt ‡ kÖYxweb¨vm msµvšÍ ÷vwÛs KwgwUÕi 02 b ‡ f¤^i 2014 Zvwi ‡ Li mfvq mIR Gi gvwjKvbvaxb moK ZvwjKv nvjbvMv` Kiv nq Ges † gvU 876wU mo ‡ Ki ZvwjKv P ‚ovšÍ Kiv nq| MZ 18 † deªæqvix 2015 Zvwi ‡ L Zv † M ‡ R ‡ U cybtcÖKvk Kiv nq| (1 1 467 ) g~j¨ : UvKv 25 2.00 11468 evsjv ‡` k † M ‡ RU, AwZwi ³, A ‡ ±vei 2 9 , 201 7 ÕmoKmg~‡ ni cybt ‡ kªYxweb¨vm msµvšÍ ÷vwÛs KwgwUÕi 02 b ‡ f¤^i 2014 Zvwi ‡ Li mfvq wm×všÍ M „nxZ nq † h ÕmIR Gi gvwjKvbvaxb mo ‡ Ki † M ‡ RU cÖKvwkZ nIqvi ci GjwRBwWÕi moKmg~‡ ni ZvwjKv nvjbvMv` K ‡ i Zv † M ‡ RU AvKv ‡ i cÖKvk Ki ‡ Z n ‡ eÕ| G † cÖwÿ ‡ Z 11 † m ‡ Þ¤^i 2017 Zvwi ‡ L AbywôZ AvšÍtgš¿Yvjq KwgwUi mfvq GjwRBwW I GjwRAvB Gi nvjbvMv`K …Z ZvwjKv -

An Internal Environmental Displacement and Livelihood Security in Uttar Bedkashi Union of Bangladesh

Applied Ecology and Environmental Sciences, 2015, Vol. 3, No. 6, 163-175 Available online at http://pubs.sciepub.com/aees/3/6/2 © Science and Education Publishing DOI:10.12691/aees-3-6-2 An Internal Environmental Displacement and Livelihood Security in Uttar Bedkashi Union of Bangladesh AKM Abdul Ahad Biswas1,*, Md. Abdus Sattar1, Md. Afjal Hossain1, Md. Faisal2, Md. Rafiqul Islam3 1Department of Disaster Risk Management, Patuakhali Science and Technology University, Bangladesh 2Department of Resource Management, Patuakhali Science and Technology University, Bangladesh 3PGD Research Student, Faculty of Disaster Management, Patuakhali Science and Technology University, Bangladesh *Corresponding author: [email protected] Abstract The climate change related hydro-meteorological disaster impacts in the coastal region of Bangladesh cause widespread loss of lives, damage of properties, infrastructure and degrade the entire environment and disrupt the ecosystem. Thus people lost their means of livelihoods, habitat, and finally they are forced to leave their land of origin. This study was aimed to investigate the factors that influence human displacement, their way of securing livelihood and how best can be reduce the vulnerability occur due to internal displacement in Uttar Bedkashi Union under Koyra Upazila in Khulna district of Bangladesh which was destroyed by super cyclone Sidr in 2007 and Aila in 2009 and caused human displacement and migration. Field investigation, focus group discussion, in-depth household survey, key informant interview and literature review methods were followed to collect primary and secondary data from January 2014 to June 2014. The study revealed that the land has become completely barren to all agricultural practices due to salinity intrusion caused by embankment failure resulted in long term saline water logging, demolish soil characteristics, creates sever unemployment problem, changed the ecosystem balance and this circumstance ultimately led people to temporary or permanent displacement to other regions to seek nonfarm livelihood e.g. -

Self-Organisation in the Governance of Disaster Risk Management In

Self-Organisation in the Governance of Disaster Risk Management in Bangladesh By MOKTER HOSSAIN A mini-thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Administration in the School of Government, Faculty of Economic and Management Sciences, University of the Western Cape. 25 October 2008 Supervisor: Prof. Christo De Coning Self-Organisation in the Governance of Disaster Risk Management in Bangladesh Mokter Hossain KEY WORDS Bangladesh Participation Governance Accountability Coordination Legal framework Disaster risk management Union disaster management committee (UDMC) Non-government organisations (NGOs) Community-based organisations (CBOs) ii DECLARATION I declare that ‘Self-organisation in the governance of disaster risk management in Bangladesh’ is my own work and that all the sources I have used or quoted have been indicated and acknowledged as complete references. Moreover, I declare that this mini-thesis has not been submitted at any university, college or institution of higher learning for any degree or academic qualification. .Mokter Hossain 25 October 2008 iii ABBREVIATIONS ADB Asian Development Bank ADP Annual Development Programme ADPC Asian Disaster Preparedness Centre BBS Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics BMD Bangladesh Meteorological Department BWDB Bangladesh Water Development Board CBOs Community-Based Organisations CDMP Comprehensive Disaster Management Programme DAP Disaster Action Plan DFID Department for International Development DMB Disaster Management Bureau DMC Disaster Management -

An Investigation Into the Adequacy of Existing and Alternative Property

An Investigation into the Adequacy of Existing and Alternative Property Rights Regimes to Achieve Sustainable Management of the Sundarbans Mangrove Forest in Bangladesh A Dissertation submitted for the award of Doctor of Philosophy Anjan Kumer Dev Roy B.Com (Hons) and M.Com in Marketing (University of Dhaka) MSc in Project Planning and Management (University of Bradford) School of Accounting, Economics and Finance Faculty of Business and Law University of Southern Queensland Toowoomba, Qld, 4350, Australia November 2012 Dedicated to The Lotus Feet of Param Doyal Sri Sri Thakur Anukulchandra i Abstract This thesis identifies theoretical gaps regarding the adequacy of property rights in achieving sustainable management in the world’s largest Sundarbans Mangrove Forest (SMF) in Bangladesh. This will be achieved through an examination of existing and alternative property rights regimes. Gaps are also pinpointed regarding non-compliance with existing policy in conservation practices and the absence of clear quantitative and qualitative methodical approaches for identifying sustained conservation determinants of the forest. This research aims to fill these gaps by addressing the questions of the adequacy of the existing property rights regime to achieve sustainability. It examines the interaction between property rights and conservation and the necessity for an alternative property rights regime of co-management. It focuses on state property rights regimes within mangrove conservation practices. The subject of this thesis is regarded as one of the oldest mangrove management systems in history, originating in 1875. The thesis adopts a mixed methods research approach involving household survey, content analysis and focus group discussions. Multiple actors, scales and techniques—with a focus on Forest Dependent Communities (FDCs) and conservation practices by the Bangladesh Forest Department (BFD)—are involved in the study. -

JJS Annual Report 2015

Annual Report 2015 01 Editor: ATM Zakir Hossain Co-Editor: Kanailal Debnath Sk. Nazmul Huda Mithila Senjuti Md. Riad Hossain Published By: Jagrata Juba Shangha (JJS) Published on: April, 2016 Documentation Support & Photo Credit: JJS archive Printed by: Procharoni Printing Press 02 About JJS JJS, Jagrata Juba Shangha, is a non-government, not for profit social and environmental development organization working since 1985 in the South-west coastal region of Bangladesh. Its initiation was in 1985 by doing voluntary works including road repairing, education for children of untouchable dalits communities, school repairing and tree plantation in Talimpur village in Khulna district by some youths led by ATM Zakir Hossain. In 1988, JJS got legal status from Department of Social Services and strengthened its community development activities with individual contribution from community until it received formal support from ADAB for relief distribution in the same year. Between 1989 and 1991, JJS intensified and expanded its activities in different sectors and received fund from OXFAM, International Voluntary Services, Australian High Commission, Asia Partnership for Human Development (APHD) CARITAS, NGO Forum for Drinking Water Supply and World Vision. Activities included institution building, adult literacy, child literacy, social forestation, and water & sanitation. In 1991, JJS got registration from NGO Affairs Bureau under Government of Bangladesh and gradually turned into a rights based organization with a standard mixing of rights and services approach and research. JJS envisions a sustainable, environmentally conscious, humanitarian, total responsive, equitable and poverty free society. It is working with people to improve their individual capital and power to fight poverty, injustice and climate change effects in the region.